Other public policy

The Reserve Bank endeavours to win friends and influence people

The ABC’s Ian Verrender notes that after being forced to play catch-up in the 'war on inflation', Australia's banking masters have subtly switched course.

While our Reserve Bank, and other central bankers around the world, are still talking about bringing inflation back down (two to three percent range for the RBA), they are becoming more patient and less aggressive in their moves, while still quietly threatening to resume their push on interest rates if we don’t behave ourselves and stop spending money. It’s the basic drill-sergeant psychology of threat and punishment.

Verrender explains how seven consecutive monthly rises in interest rates affected the economy. Their influence on the financial sector is almost immediate, but it takes time for them to take effect in the real economy. By now, although retail sales are still booming and consumer confidence has slumped, we are running down the savings we accumulated during Covid-19.

He observes that the RBA has been somewhat hypocritical on inflation. It has traditionally reacted negatively to inflation as revealed in consumer prices, while rampantly fuelling inflation in asset prices, notably housing and equities. He remarks that asset price inflation has been the main driver of wealth inequality.

In these times of rising rates RBA Governor Ian Lowe has few friends, but Peter Martin, writing in The Conversation, stands up for him: In defence of RBA Governor Philip Lowe: an easy scapegoat for record interest rate rises. Martin reminds us that Lowe has specific instructions from the Treasurer to aim to bring inflation to between two and three percent, over time.

Lest we believe that Lowe is some stooge for the economic right, Martin mentions Bernie Fraser’s record as RBA Governor. Fraser believes the RBA is on the right track, and as Martin says, Fraser should know because he succeeded in bringing inflation back to two to three percent.

Verrender’s article is a summary of most of Lowe’s remarks at the bank board dinner in Hobart, but he leaves out a revelation by Lowe that the value of Australian banknotes is over $100 billion – around $4 000 per person, or $10 000 per household, including substantial holdings of $100 notes. These are average figures: let’s not forget that many people are challenged to find the cash to give to the Salvos or to shout a round of beer, and that since Covid-19 many people have abandoned cash altogether. (Think how seldom you see someone tendering cash at a supermarket.) Are these huge sums related to money laundering, the narcotics trade, donations to political parties, or tax evasion? Should our government be heading along Sweden’s path of discouraging and perhaps ultimately abandoning cash?

More on inflation: a single number doesn’t mean all that much

Ross Gittins provocatively tells us that the cost of living isn’t as high as we’ve been told.

His article is about the way prices rise differently for different goods and services. That should be evident for anyone who compares, say, the price of electricity with the price of strawberries, but the ABS, in compiling the CPI, bundles them all up into one indicator. We touched on this in last week’s roundup where there was reference to the need for the Reserve Bank to look deeply into the detail of ABS CPI figures and other indicators of inflation.

The ABS provides a huge amount of disaggregated detail about price movements. In its food category, for example, it has separate series for pork, lamb and goat, and beef and veal. Footwear for men and women are in different series. It also publishes series for what it considers to be “discretionary” and “non-discretionary items.

Gittins draws attention to the inclusion in the CPI of the cost of building a new house, a cost inflated by global supply shortages and by policies that have stimulated demand beyond the industry’s capacity to build houses. But in any one year few of us (about I in 50) move into a new house. By contrast, under justifiable accounting measures, the ABS doesn’t include the cost of interest payments, which affects everyone with a mortgage. (It would be double-counting to include the cost of an item itself and the cost of financing its purchase).

Some Australians, including retirees who own their homes outright and who have some form of indexed pension, would hardly be noticing any change in their cost of living. But for many the cost of living pressure would be far more severe than what is revealed in economy-wide indicators such as average wages or the CPI.

Industry policy – stop thinking about “jobs, jobs, jobs”.

Over a long period two considerations have dominated industry policy. One has been a concern with creating jobs. The other has been a focus on manufacturing.

Many, including Barry Jones, have questioned these priorities. Jones once disparagingly said of the manufacturing obsession that we don’t consider an enterprise to be doing anything useful unless it produces something that hurts when you drop it on your toes.

Harvard’s Dani Rodrik has drawn up An industrial policy for good jobs, as a contribution to the Hamilton Project, urging policymakers to shift their thinking away from jobs to the economic benefits of industrial development, and to take a broad view of what constitutes “industry” to incorporate the service sector.

It’s addressed to a US readership. In relation to industry policy Australians are well ahead of Americans, but we can learn from Rodrik’s idea of “job externalities”. Bad jobs impose negative externalities on the community, he writes. “Bad jobs lead to lagging communities with poor social outcomes (poor health, inferior education, high crime) and social and political strife (populist backlash, democratic malfunction). In the absence of incentives that prompt them to do so, private employers fail to take these costs into account”. By contrast good jobs are generally well-paid and secure, and have positive externalities for the community.

This is hardly radical for most academics and policy advisors, but in the broader community, particularly among journalists and populist politicians, the story is often “jobs, jobs, jobs”.

Church and state

Both Australia and the US have constitutional provisions prohibiting the establishment of any religion, prohibiting the government from imposing religious observance, and protecting the free exercise of religion.[1] Yet the Pew Research Center finds that 60 percent of Americans believe the country’s founders considered that it should be a “Christian Nation” , and 45 percent believe today that it should be a “Christian Nation”.

This belief is one the issues discussed in a 27-minute interview on the ABC’s Religion and Ethics Report – The dangers of Christian nationalism – with Paul Miller, author of The Religion of American Greatness: what’s wrong with Christian nationalism, which Andrew West describes as a good read for an academically respectable book.

Miller comes across as a conservative liberal (that’s not an oxymoron), and he describes himself as a committed Christian. He distinguishes between Christians trying to assert Christian principles in public life, and trying to seize power: the distinction is important. Towards the end of the interview there is reference to Trump’s promise to restore Christian power. Miller is repulsed by the idea of Christian nationalism, which he describes as “idolatrous”. He also notes that social research identifies a strong correlation between belief in Christian nationalism and distinctly un-Christian attitudes to race and social inclusion.

In Australia our situation is somewhat different from America’s. Religious observance is much lower, and there does not seem to be any push for Christian nationalism.[2]

Here there were once associations of the Labor Party with Irish Catholicism and the Liberal Party with the Church of England (to use its old name) and mainstream Protestantism, but that association has long been broken. But in various states there have been attempts by the religious right to get its preferred candidates endorsed in Liberal Party pre-selections, the most recent incident being revealed in the runup to the Victorian election.

1. The First Amendment in the US, Section 116 in Australia, with very similar wording. ↩

2. Perhaps the most prominent proponent of an Australian Christian nationalism was the poet and public intellectual James McAuley, most active in the 1960s (no relation). ↩

The rental market – a bastion of paternalistic feudalism

Markets are wonderful. “The consumer is sovereign”. “The customer is always right”. If you have ever sat through economics lectures you will have seen freehand and dimensionless supply and demand curves, proving that in a market with lots of customers and where there are no barriers to entry for suppliers, all the benefits of market transactions (the “surplus”) accrue to the consumer. Q.E.D.

Although they have heaps of imperfections, most markets seem to work over the long term. Supermarkets, auto companies, and appliance stores compete for our business. While few markets match the textbook ideal, in most markets the consumer has a significant degree of power, sometimes helped by strong consumer protection law.

A glaring exception to the textbook model of a consumer-friendly market, however, is rental property. Almost a third of Australian households are renters, a proportion that’s been growing over the long term. (See the AIHW’s Home ownership and housing tenurepublication for the full story.) In this market, particularly at present, the buyer is almost powerless.

This market even has its own terminology – the words “landlord” and “tenant”, having been carried over from the exploitative conditions of feudal agriculture.

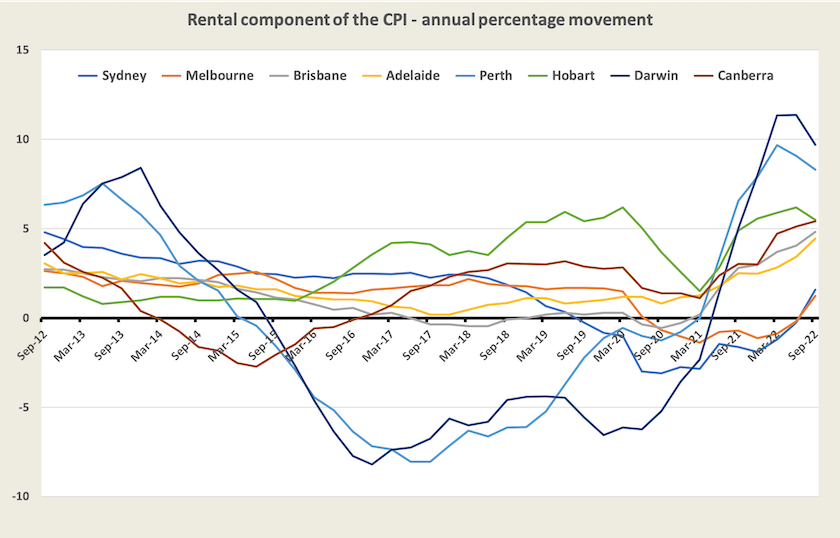

The plight of renters has become prominent in the last twelve months because there has been a recent surge in rental prices. The graph below, derived from ABS CPI data, shows the official figures. For most of the last ten years, apart from Hobart and Canberra, rents in our capital cities hardly moved, and they even fell in Perth and Darwin. In most of these capitals they fell in real (inflation-adjusted) terms. But there has been a recent surge in all these cities.

These official figures provide only part of the story, however, because the ABS samples only capital cities. There are many accounts of extreme rental property shortages and unaffordable prices in many non-capital-city regions, such as the New South Wales north coast. Covid-19 has given a huge impetus to remote working, driving up rental prices in sea-change regions.

And it gets worse. The ABS, understandably, samples all rents, new and existing. At any time only a small proportion of rentals are newly-contracted. Most rentals are ongoing, and are probably not rising – not all property owners are unconscionable thieves. New renters however, including those turfed out of their rented accommodation by property-owners, are faced with huge increases in rents, competition from bidders willing to pay over the advertised price, and demands from agents for intrusive personal information about their trustworthiness, even to the extent of demanding that they pay for their own background checks.

You can see the dubious justifications for such intrusion on a typical letting-agent’s website. It describes the “tenant screening process”: how did the “landlord or property manager” of their last rental find them? Perhaps those who have made reasonable demands for neglected maintenance, who have pointed out that the property was misrepresented by the agents, or who have complained about opportunistic rent increases above the rate of inflation, are consigned to a database of “poor tenants”.

Where are the protections one finds in markets, helping buyers check the trustworthiness of suppliers? And how are first-time renters expected to provide such information?

On the ABC’s The Money program, Chris Martin of the City Futures Research Centre at the University of New South Wales, Rachel Ong Viforj of Curtin University and Leo Patterson Ross of the New South Wales Tenants’ Union discuss the rental crisis with Richard Aedy.

They describe the drivers of the problem, including Covid-19 demand-side drivers, which have increased the demand for more personal living and working space, particularly among young people who might previously have been content with using a shared house as a convenient dormitory.

They take us through supply-side figures: extra house starts promised in the budget are a welcome reversal of the Coalition’s policies that had been about cutting public housing, but they are small compared with the backlog and normal growth in demand. There has to be much more meaningful investment in public housing.

Among solutions they put forward are increased financial support for renters: they suggest there are ways rent assistance can be designed so as not to worsen price increases. There should be more security for renters: Australia is one of the few countries that allows “no fault” evictions. And they don’t rule out forms of rent control. (Rent control has a bad name among economists, because it is usually presented to students as case studies of America’s most poorly-designed interventions.)

These are all solutions within existing frameworks. There needs to be a more basic thinking about housing, however.

First there has to be a restructuring of regulatory and tax incentives to ensure that renters can have longer-term security, allowing them to become integrated with communities in which they live, as is the case in many European cities. It is extraordinary that a political party classifying itself as “conservative” and “family friendly” was responsible for tax policies that encourage quick turnover of rental properties.

Second there needs to be a return to consideration of housing as a fundamental right, rather than as a speculative commodity. Perhaps an extended period of decline in housing prices may help to bring us back to sanity.

And the third need is a cleanup of the property development and real-estate industry, particularly letting agents. Public policies that increase housing supply, while discouraging unnecessary rental turnover, would help to drive the spivs and hucksters out of the industry.

It may be fiscal stress, rather than any consideration of equity, that prompts the government to attend to the rental market. One of the Coalition’s more economically irresponsible moves was to allow “investors” to claim interest payments as a tax deduction – egregiously irresponsible because it involves double-counting costs as tax deductions, but that’s the subject of a two-hour lecture with lots of equations. As interest rates rise that allowance is going to cost the budget more and more: when combined with the capital gains discount for short-term profits it will soon cost the budget $20 billion a year, according to the ABC’s Michael Janda.

Crispin Hull on universities’ dark secrets

Older Australians may reflect on their first days at university, when a lecturer would say “look at the person on your left, and at the person on your right: two of the three of you will most likely fail this unit.”

Crispin Hull reminds us that those days are well in the past. His article is headed Universities: who are the real cheats?, but he points out that there is no need for students to cheat when assessment has become so easy.

Don't worry: the assessment isn't too tough

Most people know that academics are forbidden from having sexual and commercial relations with students. But they may be less aware that one of the most terrible things an academic can do is to set difficult assessments for students, particularly if they are so challenging that a significant proportion of students fail. The offending academic is punished by summonses to appeals committees, and reminders from university administrators that a high failure rate does not align with the institution’s business model. Those students, particularly full-fee-paying international students, have paid a lot to come to this institution, and they expect something in return.

Hull’s article is about that culture: it is about the way universities have become corporate entities.

We need an education model, not a business model. The business model stresses: high pay for the CEO and few others; as low pay and as poor conditions as you can get away with for other staff; contracting out; and cost cutting, especially on customer service.

Covid-19

By all accounts another wave is already with us, but, either because it is less virulent than previous waves, or because we already have a substantial degree of resistance from vaccination or prior infection, it is not as likely to cause severe illness as earlier waves.

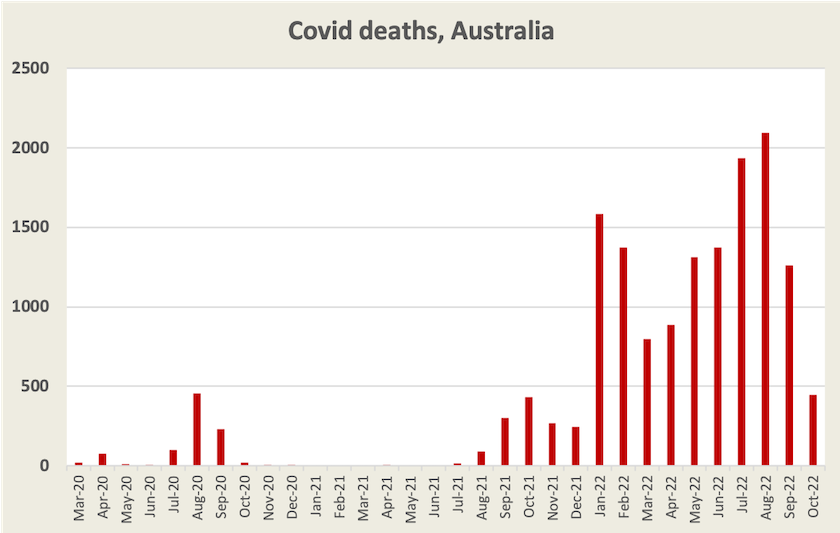

Deaths from, or with, Covid-19 were down in October, as shown in the graph below.

It is possible that this wave will spread more quickly than previous waves, aided by a substantial relaxation of the rules about isolation once an infection is evident: in most states measures that were mandatory are now “recommended”, and eligibility for compensation payments for those who are absent from work because of Covid-19 is now severely restricted.

Australians don’t get around much any more

The pandemic has brought forth many stories about people who have reflected on their lifestyles and decided to quit their jobs in favour of some other paid or unpaid pursuit: the finance executive who becomes an artist, the salaried engineer who takes the leap into self-employment. There are stories about “the great resignation”.

Even before the pandemic industrial socialists were writing about “the end of the career”, as people would move from job to job, with their portfolio of skills.

The ABS has put paid to these stories, however, in a special report on job mobility. Over the last 50 years we have become far less likely to change jobs in any one year. In 1972, 17 percent of Australians changed jobs in that year. In 2000 only 8 percent of us changed jobs. And our workforce participation remains at high levels. This is in spite of portable superannuation that should have made changing jobs less costly. As economists point out, when employers are stubborn on wage rises, the best way to get a pay rise is to get a new job.

The ABS notices some uptick in job mobility in the twelve months to February 2022. Unsurprisingly, in our tight labour market, fewer people are getting retrenched, and there has been a leap in the number of people who have shifted employment “to get a better job or just wanted a change”.

This publication has a great deal of data on job mobility by industry of employment and some by occupation. There are not many surprises: professionals are the most likely group to change jobs, and they are the least likely to change occupation, while sales workers are the most likely to shift to a different occupation.

The data shows that out of its 20 industry classifications, the greatest mobility, in the number of people leaving their jobs and in the number of people taking up employment, has been in “health care and social assistance”. Also the number of people leaving that sector is well up on 2021. That aligns with the general concern that health and aged-care workers are overstressed.