Energy policy

Electricity prices: too much partisan gut feeling, too little analysis

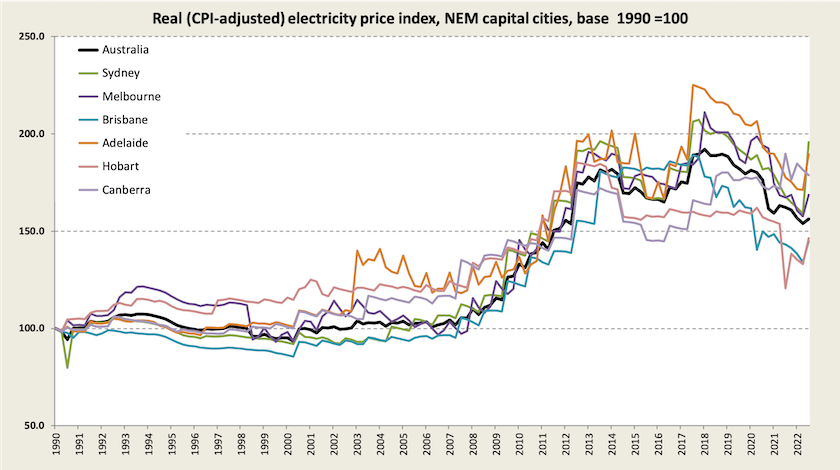

Over the last 30 years electricity prices in Australia have risen by 250 percent, or by 50 percent in real (CPI inflation-adjusted) terms.

These are national figures, but when we dig into them at a state level we see that the price rises have been concentrated in states served by the neoliberal monstrosity known as the National Electricity Market. In Western Australia and the Northern Territory, which lie outside the NEM, real prices have hardly risen.

The graph below shows an index of electricity prices in the NEM since 1990. Most noticeable is the sudden jump in the latest quarter – 23 percent in Sydney and jumps of around 10 percent in other capitals. Even in Tasmania, which is self-sufficient in hydro power, there was a jump of 10 percent.

While the immediate and expected price rises can be attributed to Putin, the NEM, along with our tardiness in investing in renewable energy, carry much of the blame for the long-term rise in electricity prices.

Note that the escalation in prices started around the turn of the century. That’s when the NEM got underway, replacing the vertically-integrated state-owned utilities with the structurally-separated and largely privatized generating, transmitting, distributing and retailing entities. The economic absurdity of these arrangements was covered in last week’s roundupin relation to Victoria’s sensible decision to start re-nationalizing its network.

An ideologue of the “left” would attribute all this price rise to privatization, but even if the state-owned utilities had been retained they would have had to invest heavily in new assets: they had been running on a wave of coal-fired expansion in the 1980s and had been using transmission networks ill-suited to the needs of new renewable supplies. The rest of the price rise, however, is largely explained by privatization. It is notable in the graph above that Queensland, which has not gone down the privatization route as far as other states, has not had such severe price rises.

Notice too the blip in prices between 2012 and 2014. This was when the Gillard government’s carbon price was in place. Had Abbott not repealed it we would now have more low-cost renewable supply in our system.

What now?

According to projections published in budget papers, in the absence of any policy interventions, electricity prices could rise by 20 percent next year and by 30 percent in the following year. That’s 56 percent compounded.

The issue has become highly partisan: for example the Financial Review has an article: Labor’s power prices promise dead: energy costs to spike 56pc, which asserts that household bills will rise by 56 percent. Is this confusion of bills and prices partisan or is it just sloppy journalism? The difference is substantial, as we discussed last week. If prices rise consumption falls: that’s Economics 1.

The more relevant question is about the government’s intentions concerning this situation.

The Grattan Institute’s Tony Wood outlines four options – a cap on wholesale gas prices, a windfall profit tax on gas producers with some of the proceeds subsidizing consumers, a gas reservation policy as used in Western Australia, and price control through establishing a price that would prevail in a theoretical competitive market (a common form of price control): How will Labor rein in energy prices?

Rod Sims, writing in The Conversation, favours a cap on wholesale gas prices. The Commonwealth already has powers to control the market through its capacity to regulate exports. Contrary to what some in the industry might assert, a price cap favouring domestic users would not jeopardize gas companies’ export markets or impose a sovereign risk. A price cap is quite in line with what other gas exporters do: Cheaper gas and electricity prices are within Australia’s grasp – here’s what to do.

Samantha Hepburn, also writing in The Conversation, puts the case for a domestic gas reservation policy: Will your energy bills ever come down? Only if Labor gets serious with the gas majors.

It is worth remembering that for many households that have invested in insulation, photovoltaic panels, batteries and smart metering systems, any electricity price rise will pass unnoticed. These tend to be the wealthiest households. Rohan Best of Macquarie University in his Conversation article We all need energy to survive: here are 3 ways to ensure Australia’s crazy power prices leave no-one behind addresses equity issues in any scheme to help consumers deal with electricity prices: the schemes we have at present do not necessarily help the neediest households.

The government is coming under a great deal of pressure to do something about electricity prices. On Thursday’s ABC Breakfast program Ed Husic, Minister for Industry and Science, dropped hints that the government is tending to favour price caps on gas companies, as well as converting agreements between gas companies and the government into formal and enforceable rules: How will the government bring down power prices?. (13 minutes)

It is notable that Husic seems to be getting more exasperated by the behaviour of gas companies. In their negotiations with government they display their strong market power, for example by suggesting they might set domestic prices that are higher than they could command on export markets. Husic complains of their “glut of greeed”.

Husic’s interview is followed by a short interview with Shadow Finance Minister Simon Birmingham, who trots out the old line that the government should expand gas supply (that would take many years) and warns Labor not to upset the gas industry – an industry that earns so much income for Australia (little of which stays in Australia).

The government is understandably cautious, and is probably waiting until pressure builds up for it to do something, particularly from electricity and gas intensive industries. It remembers what happened in 2012 when the Gillard government introduced a minerals resource rent tax: the Coalition, guided by its single objective of throwing Labor out of office, and disregarding the economic case for the tax, sided with the mining industry to run a savage and deceitful campaign against the government. Birmingham’s interview provides no indication that the Coalition’s tactics have changed.

A responsible opposition would be chastising the government for not taking on the gas companies, but the Coalition has too many mates in those businesses.

Public opinion – in favour of intervention, but partisan

This week’s Essential Report has two questions on energy prices.

The first is about what people believe to be the most important drivers of expected energy price increases over the next two years. The responses are:

- Excess profits by energy companies, 38 percent;

- Efforts to fight climate change, such as the shift towards renewable generation, 34 percent;

- Australia’s energy network becoming old and worn out, 34 percent;

- International circumstances such as the war in Ukraine, 33 percent;

- Too many restrictions on oil and gas exploration, 24 percent.

Coalition voters strongly believe that climate change efforts are the problem, and they also tend to blame restrictions on oil and gas exploration. Older people are much more likely to blame energy companies than younger people.

The other question is “Can the government make a meaningful difference on energy prices?”. In response 67 percent of people surveyed believe they can, 20 percent believe they cannot. There is no significant partisan difference.

Resolve Strategic (reported in William Bowe’s entry on post-budget polls) asks people about possible measures to bring down the price of electricity. Price caps come out on top (79 percent), but there is also more than 50 percent support for subsidies (for people on low income and for investment in solar power) and reserving gas for the local market. The message from the public seems to be “just do something”.

World energy outlook – peak fossil fuel is upon us

On the same day that Peter Dutton delivered his reply to the budget, rubbishing the government for its haste in its policies for a renewable energy transition, the International Energy Agency produced its World Energy Outlook 2022, demonstrating that the global energy crisis, precipitated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, has hastened the world’s transition to renewable energy.

The disruption to the world economy, manifest in outbreaks of inflation, is on the same scale as the oil crises of 1973 and 1979, but this time countries have the opportunity of accelerating their transition to clean energy sources, particularly for electricity and transport.

The world will reach peak fossil fuel within the next few years. Coal is already on the way down, and while LNG has enjoyed tremendous growth over the last ten years, demand is stabilizing.

This report is an outlook: it is not a policy prescription. If the developments modelled by the IEA are carried through, they will have capped global warming to 2.5 degrees rather than 3.5 degrees, but they fall well short of what is needed to achieve net zero by 2050. The clear implication is that if we are to meet that target LNG has to go.

From the link above you can read the summary, follow a link to the full report, or watch a YouTube presentation. The main figures, some of which are staggering in terms of the clean energy investments ($US trillions), are in the presentation from 20 to 44 minutes.

Peter Dutton is right: there will be investment in nuclear power, but at a tiny level compared with renewables. And when the Coalition harps on about energy reliability and security needing base-load fossil fuel-based supply, they are out of step with other “developed” countries that are investing in clean energy in order to improve their energy security. A diversified portfolio of wind, solar and storage, in different climate zones, is probably more secure than reliance on a handful of nuclear or gas power plants.

The main policy question for Australis is whether there is any point in going on with exploration for gas. As the IEA points out, gas is vulnerable to measures countries will probably take to meet tough emission targets, but even if they don’t take such measures, gas demand will at do more than level out.