Echoes of the budget

The budget’s big weakness: tax cuts

No government, particularly a Labor government, wants to wake up to headlines from an independent media source asserting that its first budget back in government will make income inequality worse.

That’s the headline on the ABC’s Gareth Hutchens’ assessment of the budget, based on a paper by Ben Phillips and his colleagues at ANU’s Centre for Social Research and Methods: Distributional Modelling of 2022/2 Federal Budget.

Phillips and his colleagues note that the budget includes the stage 3 tax cuts, and look at its distributional consequences in two dimensions – by income and by region.

By income the greatest share of benefits goes to households in the highest income quintile. When they look at distribution based on disposable income, incomes in the two lowest quintiles go backwards.

The explanation for this inequitable outcome lies in the tax cuts. But for those tax cuts, the distributional consequences would be minor, with some gains for middle-income households because of support for child care and parental leave pay, but not enough to affect income distribution significantly.

They present their regional analysis in a series of colour-coded maps, revealing that the benefits are concentrated in well-off urban regions in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane, while there is hardly anything for the rural regions of New South Wales and Victoria. (They do not cover the other states.)

These maps could be overlaid with electoral maps of political representation (a task some reader might wish to undertake). Almost all the regions that get next-to-nothing from the tax cuts would lie in National Party electorates, and in some cases Liberal Party electorates. So why are the National Party, and Liberal members such as Dan Tehan and Angus Taylor whose electorates are rural, not criticizing Labor for hanging on to the Stage 3 tax cuts?

Budget grizzles and cheers

It takes a few days for people with specific interests to go through the budget papers and draw matters to public attention – a sneaky cut in a program’s allocation, a re-definition of eligibility for a grant, and sometimes a reform that didn’t make it into the budget speech or the lockup press briefings. Below are a few such assessments.

Not enough on climate change. Writing in The Conversation Timothy Neal of the University of New South Wales writes:

The budget earmarked a suite of worthwhile climate-related measures, but many are relatively piecemeal. As extreme weather events occur at a record-breaking frequency and severity, federal spending on climate action still falls well short.

He goes on to list initiatives the government could have taken, such as larger capital investment in renewable generation and battery storage, and some they could still take, such as a ban on logging in old-growth forests, which don’t require appropriation of funds. Labor’s “sensible” budget leaves Australians short-changed on climate action. Here’s where it went wrong.

Not much for the arts. Jo Caust of the University of Melbourne believes the arts could have done better. In her article in The Conversation – This was supposed to be a “wellbeing budget” – so why does it feel like the arts have been overlooked? – she points out the arts have suffered from many terrible years. They have endured cultural vandalism inflicted by the Coalition and restrictions inflicted by the pandemic. She lists the contributions the government has made, including $84 million restorative funding for the ABC, but other appropriations have been small.

Putting those million homes in perspective. A million new houses over five years sounds impressive, but as Hal Pawson points out in The Conversation it doesn’t imply a large boost over the 800 000 to 1 000 000 new homes we have been building in recent five-year periods: 1 million homes target makes headlines, but can’t mask modest ambition of budget’s housing plans. He lists measures that could give a substantial boost to housing supply, including more investment in social housing, simplification of planning laws, and changes in migration, tax, social security and financial regulation policies.

Health hasn’t done too badly. There have been media reports that billions have been slashed from the budget for hospital care, but these reports seem to be based on a misreading of budget data. Writing in Croakey, Charles Maskell-Knight takes us through the figures, pointing out that there has been no decision to cut any significant aspect of health expenditure. Most health care expenditure is activity-driven. Why media reports of Budget hospital cuts are wrong.

The NDIS is not just a cost: it’s also an investment. There is a huge amount of publicity around the cost of the NDIS, but as Helen Dickinson and Dennis Petrie point out in The Conversation, it is an investment in people’s wellbeing and ability to participate in the economy, and it results in savings in other government programs, such as hospital care: The budget sounded warnings of an NDIS ‘blow out’ – but also set aside funds to curb costs and boost productivity. On ABC Breakfast Laurie Leigh of National Disability Services, the peak body for non-government services, while acknowledging that some firms have been overcharging, questions the NDIS cost projections. (11 minutes)

Welcome tweaks to programs. Crispin Hull describes the way the Treasurer and Finance Minister have been “assiduously combing through tax arrangements, tweaking here and there to remove perks for the well-off. It is the reverse of Coalition governments assiduously going through welfare arrangements cutting any butter and jam from the bread ration”: Diligence, not bread and circuses.

Hull describes the ending of a rort related to franked dividends. In 2019 Labor went to the election with a dopey policy of restricting franking credits – a policy which would have diverted Australians’ investments away from domestic growth assets and into housing and foreign equities, and which would have hit some not-so-well-off retirees hard. The present government’s reforms are more carefully considered, in that they end the rort that allowed a significant portion of capital returns to shareholders to be considered as franked dividends.

He recommends a few other tweaks to make the tax and transfer system fairer, including re-definitions of “income” for determination of exemption from the Medicare Levy and eligibility for a Commonwealth Health Card.

Could the Reserve Bank be replaced by a simple algorithm?

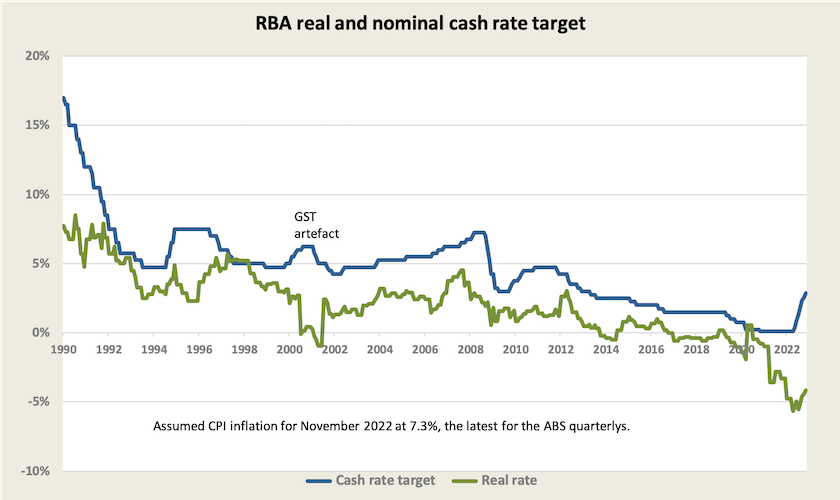

The Reserve Bank’s statement on Tuesday, when it lifted the cash rate target by 25 basis points, was pretty much in line with predictions. Although it expresses a fair bit of uncertainty about developing global and Australian conditions, it “expects to increase interest rates further over the period ahead”.

Although it recognizes “that monetary policy operates with a lag and that the full effect of the increase in interest rates is yet to be felt in mortgage payments”, and that wage growth “remains lower than in many other advanced economies”, it has gone ahead with this rise.

Anticipating a 25 basis point rise, the Commonwealth Bank’s Gareth Aird explained on Monday’s ABC Breakfast how such a rise would affect mortgage holders and other heavily indebted households: RBA expected to lift interest rates again. Some households are already experiencing mortgage stress, the 2.75 percent rise in interest rates having probably used up any buffer against interest rate rises for those who took out the highest affordable loan.

He also explained that in terms of consumer spending, which is the Bank’s main concern, the effects of earlier rate rises are yet to be manifest. There are big lags before monetary policy takes effect.

Disappointingly the RBA simply takes the most recent CPI result of 7.3 percent consumer inflation as a given single figure, without going into the drivers of that rise – the extent to which price rises of different components result from cost or demand pressure, and the likelihood or otherwise of their self-correcting. In sectors where companies have monopoly power and costs are fixed, reduced demand can result in higher, not lower prices.

Is there any reason why the RBA could not be replaced by a computer, hard-wired to the ABS to pick up CPI rises, and connected to a printer to issue monthly press releases? That would preserve the independence of the process, while saving the $430 million annual costof administering the bank.