Other public policy

How two state governments undermined our capacity to speak on human rights

Walls of the Parramatta slammer, designed to keep out nosey inspectors

In 2017 the Australian government, then headed by Malcolm Turnbull, ratified the United Nations Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. Earlier this month Lindsay Pearce and Stuart Kinner of Curtin University, writing in The Conversation, wrote that a UN delegation would be visiting Australia, making unannounced visits to prisons and other places of incarceration: Why is a UN torture prevention committee visiting Australia?. Our standards may not be as low as those in many other countries, but Pearce and Kinner list many instances where our behaviour has been wanting.

The delegation has come and gone. It suspended its visit, having been denied access to all establishments in New South Wales and to mental health wards in Queensland, by those states’ governments. The UN Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture has described this lack of cooperation as a clear breach by Australia of its obligations. Their comments are echoed in an 11-minute interview on ABC Breakfast with Alice Edwards, the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, and in a statement by the Australian Human Rights Commission. Malcolm Turnbull has warned the governments of New South Wales and Queensland that in blocking the inspectors they were keeping some bad company.

Queensland put up the excuse that out of concern for patients’ safety it was bound by law to limit certain visitors’ access. That’s a hard one to figure out when the intended visit was by people whose concern is with the safety of those who are incarcerated. The New South Wales government put up an even weaker set of excuses that aren’t worth summarizing.

On the ABC’s Law Report the first 18 minutes are devoted to an interview with Justice Aisha Shujune Muhammad, the head of the delegation that came to Australia. She explains carefully what the delegation does and does not do, the ways it normally goes about its business, and the way it regards the practices of sub-national governments. In having its inspection suspended, Australia joins the company of only three countries that have been subject to suspension or termination – Azerbaijan, Rwanda, and Ukraine.

Constitutionally state governments aren’t responsible for foreign relations, but their actions can have adverse consequences for our foreign relations. When we complain about conditions in prisons and detention centres in China or Iran, our credibility and negotiating strength are weakened when governments of those countries can legitimately refer to our refusing entry to UN inspectors.

Electricity is coming back into public hands

One hears three arguments for privatizing government businesses.

They are generally fallacious, particularly in the case of electricity.

The first, is about the private sector’s ability to raise capital because the government is constrained in its ability to do so. That’s a weird argument: if we need to raise $500 million for a new transmission line, whether it’s through private institutions or governments, it makes the same $500 million demand on financial markets. The only difference is that regardless of project risk, the private sector usually expects a higher return on investment than the government, meaning that the finance is more expensive. When the private financial sector complains about governments “crowding out” the private sector, it means they are being denied their opportunity to make big and unjustified profits.

The second is about the marvels of competition, which is supposed to force prices down and bring about product and process innovation. The trouble is that, apart from electricity generation, most parts of the electricity supply chain are natural monopolies supplying most customers with a basic undifferentiated commodity, and the technologies of transmitting and transforming electricity are about 120 years old. Electricity is the quintessential undifferentiated commodity: apart from some large customers, we all want our electricity at 240 volts, 50 cycles, with a power factor close to 1.0.

The third is some notion that government enterprises are intrinsically inefficient, and overstaffed with dull and lazy overpaid and underchallenged employees, in contrast to the hard-working and innovative private sector. Whoever sincerely believes this has never observed the insurance, real estate and other transactional businesses in the private sector, or if they want to see the opposite work culture, government enterprises such as public hospitals.

These could be ours again

That’s the context for the Victorian government’s promise, if it is re-elected, to re-establish the State Electricity Commission, which will slowly bring parts of electricity transmission and distribution, and some renewable-sourced generators, back into public hands. The imperative is to meet the government’s objective of a 95 percent renewable supply by 2035, which the government reasonably believes the private sector cannot achieve. The Grattan Institute’s Tony Wood explains it in a Conversation article: Victoria signals end of coal by announcing a new 95% renewable target. It’s a risky but vital move. Sophie Vorrath has a similar explanation in Renew Economy: Victoria fast-tracks coal exit with target for 95 pct renewables by 2035.

The Australian Energy Council, unsurprisingly, has a different view in a press release: Victoria’s “Back to the Future” a retrograde step. This re-nationalization “looks likely to chill out private investment”: that’s right, there will be less opportunity for private financiers to make high profits in low-risk monopolies regulated by compliant regulatory authorities. It goes on to state that “Victorian taxpayers carry the lions’ share of risk around new generation”: that too is right, and they will carry the lions’ share of equity, as they did 100 years ago when John Monash established the State Electricity Commission. John Quiggin, writing in The Conversation, takes on these arguments: Labor’s love lost: the tide is turning on private ownership of electricity grids. (One may reasonably ask if the tide of public opinion ever was in favour of privatization.)

Another aspect of Victoria’s move, on which there has been little commentary so far, is that it can bring electricity supply back into one entity, responsible for everything along the supply line of generating, transmitting, distributing and retailing electricity, as had been the case with the state-owned utilities. Those who established the National Electricity Market, guided by the ideology of “structural separation”, broke up these utilities into separate components, believing that somehow “the market”, with a little regulation of monopoly elements, would produce efficient outcomes. They disregarded the transaction costs of multiple entities dealing with one another, the costs of maintaining regulatory authorities, and the opportunities for generating companies to game the system. Markets may be able to work when all suppliers have much the same technologies, but in electricity the generators range from households with a couple of KW of solar panels through to ancient 3 GW coal-fired power stations selling electricity at marginal cost because their assets are completely written down. The NEM has never managed to achieve a low price in the middle of the day when rooftop solar is most plentiful, for example.

A well-managed publicly-owned electricity utility, like the State Electricity Commission, should be able to achieve what the “retailers” could never do – a pricing structure that aids an efficient transition to renewable energy and provides justice for the poorest consumers, because the functions of transmitting, distributing and retailing electricity will be in one entity. The task is one of long-term planning to ensure adequate 24/7 supply, and the day-to-day, hour-to-hour engineering task of real-time efficient matching of demand and supply. There will be a mixture of businesses supplying electricity, some of which may be government-owned. That will require some regulation to ensure a degree of competitive neutrality, but it will be a much simpler system than the byzantine set of arrangements that make up the NEM. (Think of air traffic control as an analogy: we don’t subject airlines to a bargaining system for allocation of take-off and landing slots, but that was essentially how the NEM tried to operate.)

Health policy – more waste than theft

Could Medicare do better?

Margaret Faux’s PhD thesis, which concluded that about a third of Medicare’s budget is being lost through maladministration and fraud, set off a lively, but so far not very illuminating, debate. I provided links to it in last week’s roundup, and in response, two readers, more familiar with health policy than I am, suggested that there is substance to Faux’s claims. One reader pointed out the extraordinary provision under the Health Insurance Act which gives the AMA a veto over the appointment of the Professional Services Review, the regulator that examines and supposedly acts on cases of fraud and inappropriate billing. See the ABC’s report Medicare watchdog investigates just 100 cases of inappropriate billing every 12 months, where it reports that the PSR investigates just 0.07 percent of medical professionals a year.

This is in the context of the joint investigation by the ABC, The Sydney Morning Herald, and The Age into fraud and inappropriate billing. It states that the regulator “is chronically understaffed and underfunded, and is led by bureaucrats with strong links to the powerful Australian Medical Association”.

The AMA has been highly critical of Margaret Faux’s work, and very defensive about the behaviour of medical professionals. In response, writing in The Sydney Morning Herald Adele Ferguson debunks the AMA’s debunking of Margaret’s work: AMA president admits he hasn’t read the Medicare research he claims is wrong.

So far the argument is on a “you claim”/“I claim” level, with the binary choice of seeing doctors as a bunch of thieving hucksters or as paragons of professional ethics.

Former deputy Chief Medical Officer Nick Coatsworth (the fellow we saw so often on our screens in the early days of the pandemic), writes in the Sydney Morning Herald Don’t protest too loudly, doctors – we do have a Medicare crisis. There is indeed waste, over-servicing and fraud. The regulatory system could be improved to ensure better compliance: more substantial penalties could be a good place to start. Coatsworth’s main concern, however, is the waste resulting from resource misallocation associated with low-value care. He writes that:

… the real threat to Medicare, and our world-leading universal healthcare system, is not fraud. It is the insidious billing of perfectly legal but low-value care. Low-value care is care that provides little or no benefit, may cause patient harm, or yields marginal benefits at a disproportionately high cost.

He is particularly critical of the way primary health care is funded almost entirely on a fee-for-service model, and the way that large corporations and private equity firms, owners of “super clinics”, are creaming off profits from Medicare.

Writing in the Saturday Paper – Corporate misincentives – John Hewson echoes Coatsworth’s concerns about the way corporations are taking money from Medicare, and he goes further in criticizing the whole neoliberal fad of corporatization and privatization:

It is most unfortunate, and should be a matter of much greater concern, that the provision of so many of our essential services – such as telecommunications, power, aged care, disability care and childcare and training services – are similarly tainted by bad corporate behaviour.

Covid-19

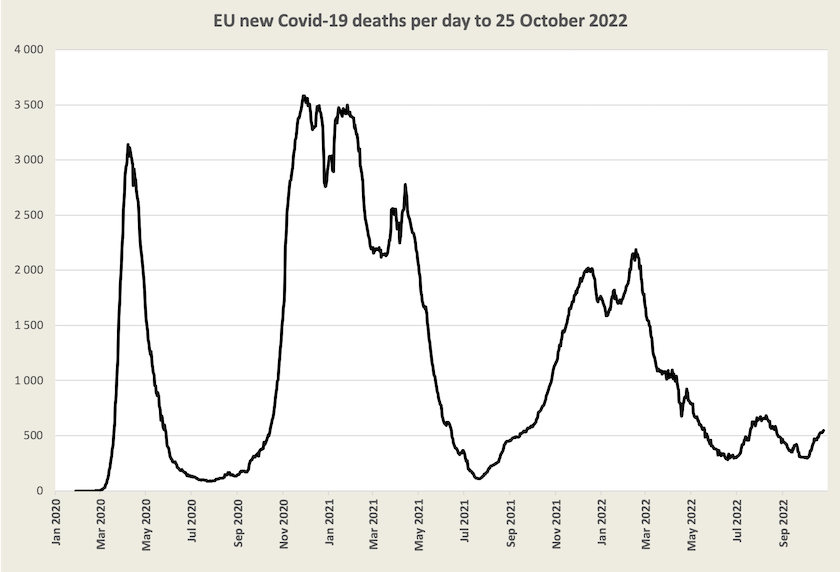

We’re still keeping an eye on Covid-19. Worldwide and in Australia real-time data is becoming patchier, however. In the EU deaths are rising again, and are now around 1.0 daily deaths per million population, but they are still about half that rate in South Korea and Japan, another region where winter is approaching.

Deaths in Australia are still falling – around 9 a day (0.3 per million population) in early October according to the Commonwealth’s Covid-19 case numbers and statistics website. But reported case numbers are no longer falling: in the week to October 25 they rose by 2.2 percent. The number of people in hospital and in ICU is no longer falling: there are around 1400 Australians in hospital with Covid-19, 40 of whom are in ICU.