The budget and all that stuff

Labor’s radical departure from precedent: an economically meaningful budget

Strictly, a government’s budget is simply an act to authorize public expenditures. It does not even authorize changes in taxation: tax changes are often announced in the budget speech, but they are subject to separate legislation.

At the Commonwealth level, however, the budget is more than a simple appropriation bill. It’s a statement of the government’s economic and fiscal policy, in a setting of political theatre, played for a domestic audience of voters and an international audience of financiers.

Increasingly over the last 20 years, particularly under Coalition governments, the budget has narrowed to a fiscal focus. That is, the emphasis has been on the cash deficit or surplus, and the level of government debt, with an assumption that public expenditure must be contained within a capped level of taxation – magically set at 23.9 percent of GDP. If the size of government can be contained, the economy will largely look after itself. Supported by partisan media, and by journalists with little understanding of economics, the Coalition has spread the idea that the only matters that count in economic management are balancing the government’s bank account and keeping government small.

Last Tuesday’s budget presented by Treasurer Chalmers breaks from this pattern. It’s not just about finance: it also has a strong emphasis on economic adjustment, much of which is evident in the budget speech, with the substance in the main budget document Budget Paper 1, Budget Strategy and Outlook. This shift in emphasis from finance to economics is foreshadowed in three parts of the Treasurer’s speech.

First is the statement that “deliberately keeping wages low is no longer federal government policy”.

Second is the emphasis throughout the speech of “investment” in skills, child care, education and other elements of government expenditure. In accounting conventions these are seen as recurrent expenditures, but to this government they are framed as investments in a stronger economy.

Third is the plan for transforming of Australia’s industrial structure, centred on renewable energy, the Powering Australia Plan.

That is not to suggest that Labor has abandoned fiscal management. To the disappointment of many this is a fiscally conservative budget. No matter what ideas such as Modern Monetary Theory or other models suggest, governments must convince the financial community, including central banks, that they are prudent bookkeepers. The international financial community has just demonstrated that if it doesn’t like what it sees, it can bring down the conservative prime minister of the world’s sixth largest economy: imagine what it could do to a social-democratic government in a mid-sized economy.

But contrary to the rhetoric of Coalition governments, fiscal bookkeeping is only one aspect of economic management. In those three aspects, Labor has shifted the budget’s emphasis to economic management.

The fourth economic aspect, hardly mentioned in the budget speech, is the statement “Measuring what matters”, a key chapter in Budget Paper 1.

Some may say that this statement is a sop to the soft left, in which the government defends its credentials among the woke community. Such an interpretation is not only cynical; it is also a misunderstanding of economics, for what is the point of a high GDP, a low level of unemployment, and low inflation (the usual trifecta of macroeconomic objectives), if they do not contribute to people’s wellbeing?

The economic outlook – gloomier than it was in May

The government’s fine intentions have been mugged by the realities of Putin’s war, resulting in a surge in energy prices, and worldwide post-Covid disruptions to supply, resulting in inflation and a predictable response from monetary authorities, who have raised interest rates.

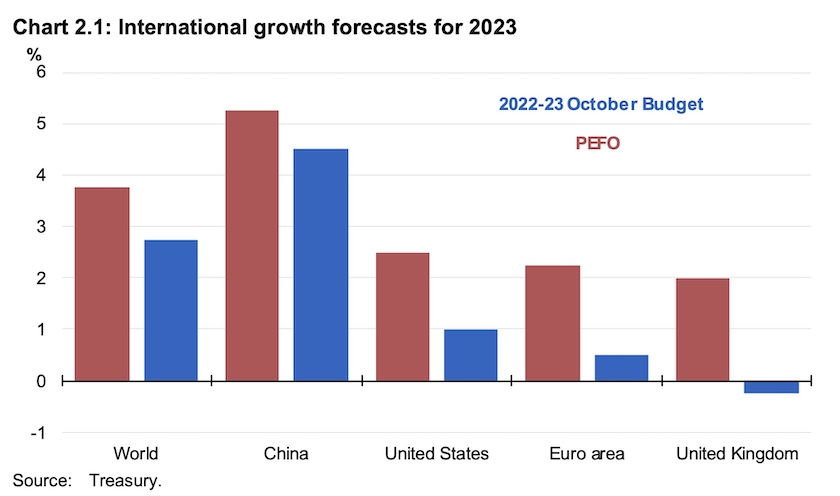

In Budget Paper 1 (pp 35 to 43) is the outlook for the international economy, showing how sudden the downturn in the world economic outlook has been. That economic outlook is much more sombre than it was when we went to the polls in May.

The chart below, copied from that budget paper, shows how that outlook changed between March, when the pre-election fiscal and economic outlook was prepared, and October when this budget was presented.

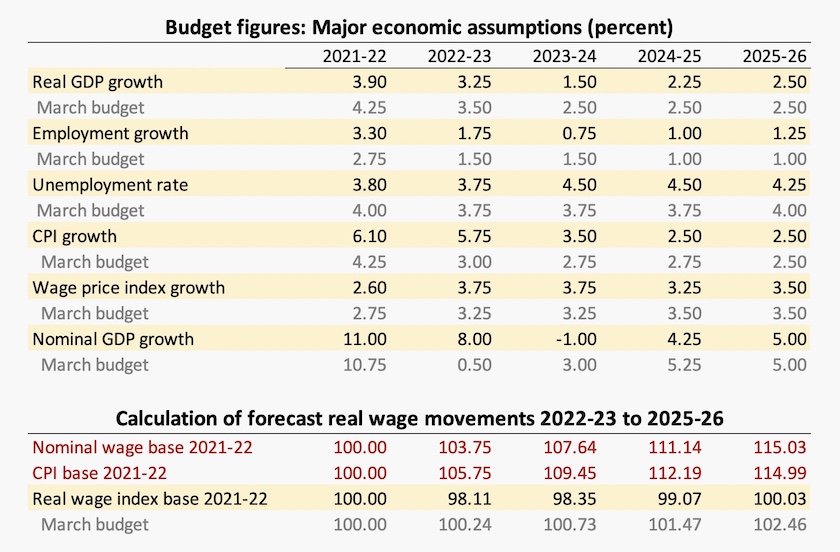

This change in the world outlook is reflected in a more pessimistic short-term outlook for the Australian economy, shown in the table below, which compares the major assumptions in this budget with those in the Coalition’s budget in March.

Note the substantial downturn in GDP growth in 2023-24 (largely explained by a predicted fall in presently-high commodity prices) and the dismal outlook for real wages. In March Treasury was expecting real wages to start rising in 2025-26, but that rise has been pushed out by at least a year.

It could be worse than this table suggests. Given the lead time in preparing budget documents it is unlikely that these figures fully incorporate the inflationary impact of the recent floods in eastern Australia.

Not revealed in these aggregate figures is a probable widening inequality in wage outcomes, because skilled workers in profitable industries subject to labour shortages should be able to bargain for substantial wage rises, while others will be left behind. Workers on the public payroll, including teachers, nurses and aged care workers will benefit from the government’s support for a rise in minimum wages and linked awards, but they are unlikely to enjoy the gains enjoyed by similarly skilled workers in the private sector.

Notably an almost immediate rise in nominal wages (but not real wages) is forecast. This may help those who are carrying debt, because debt is held in nominal terms, but it won’t do much for those with large and recent mortgages, subject to rising interest rates.

As an ameliorating factor, in allocations for human services, including child care, and lower-priced pharmaceuticals, there will be some rise in the social wage. In past periods when it has been in office Labor has emphasized the importance of the social wage, particularly when implementing major reforms such as Medicare, but in this budget the social wage benefits are too minor and not sufficiently universal to allow Labor to emphasize it.

That’s unfortunate, because there is too much emphasis on people’s pay packets, and not enough on the benefits of publicly-provided education, health care, infrastructure and other public goods. There is little point in people enjoying a $X pay rise or tax cut if they have to outlay more than $X in private markets to pay for what was provided at no charge by government. If Labor is to escape the tight fiscal squeeze that constrains it from implementing social-democratic policies, it has to talk more about the social wage, so that people can understand that higher taxes can be associated with higher real incomes.

Fiscal outcome and outlook – why do we keep putting off a rise in taxes?

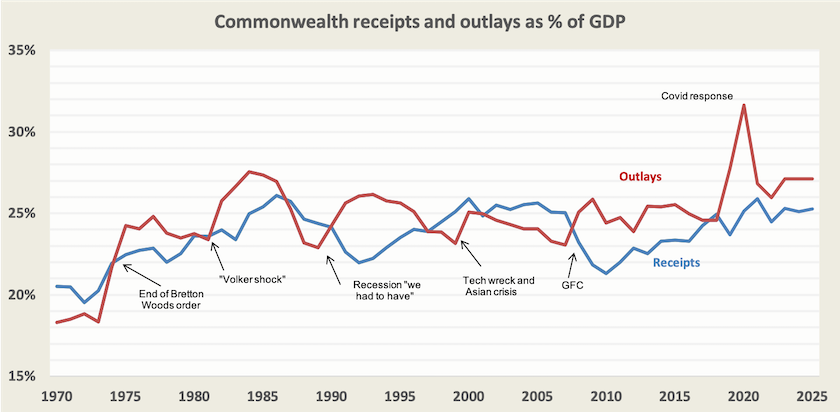

Most media attention is on the short-term fiscal outcomes, but it’s useful to look at the Commonwealth’s fiscal situation over the long-term, shown below in a graph, which includes projections to 2026. It is notable that even though the government foresees a return to more normal economic and fiscal conditions by that time, Commonwealth outlays are expected to remain elevated from past levels, to settle at around 27 percent of GDP.

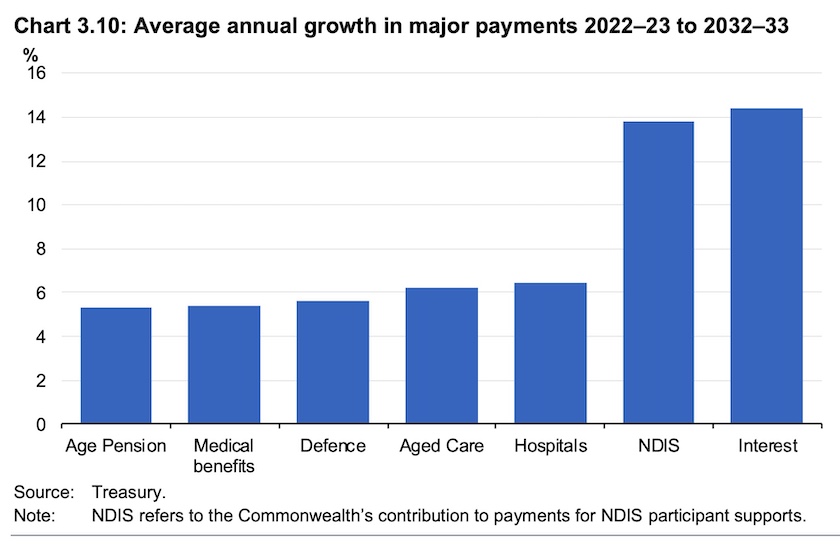

That new level of outlays reflects the demands placed on the budget by growing outlays on defence, and on human services including health care, aged care and disability services, just to maintain the existing level of service. The chart below, copied from Budget Paper 1, shows how these outlays are expected to grow in the short term. When you consider these estimates of 5 to 14 percent growth, realize that these are about compound growth. Even a 5 percent growth implies a doubling in 14 years, and a 14 percent growth a doubling in 5 years.

At the same time as expenditure is expected to level out at 27 percent of GDP (and that may be optimistic), government receipts are expected to level out at about 25 percent of GDP – 23 percent taxation receipts, 2 percent non-taxation receipts. That long-term difference between outlays of 27 percent of GDP and receipts of 25 percent of GDP, persisting once the noise of short-term disruptions is filtered out, is known as a structural deficit.

Some economic hardliners, oblivious to the damage the “small government” philosophy has already inflicted on the Australian economy, suggest that the structural deficit should be closed by cutting government programs. More economically responsible commentators have been concerned by our low level of taxation in comparison with the levels in other “developed” countries.

Many had hoped that this budget would see some action to increase taxation revenue. At least the budget papers do not refer to the Coalition’s inane arbitrary taxation cap of 23.9 percent of GDP, but it does not indicate any plan to raise taxation revenue, and there is still a commitment to the stage 3 tax cuts. (Note on Page 164 of Budget Paper 1 that personal income tax receipts are forecast to fall by $6 billion in 2024-25). Nor is there any winding back of concessions applying to superannuation fund earnings (Page 169), costing public revenue $20 billion a year – roughly 1 percent of GDP. And the traditional Labor promise to crack down on family trusts is missing from the budget papers.

Measuring what matters – the real purpose of economic policy

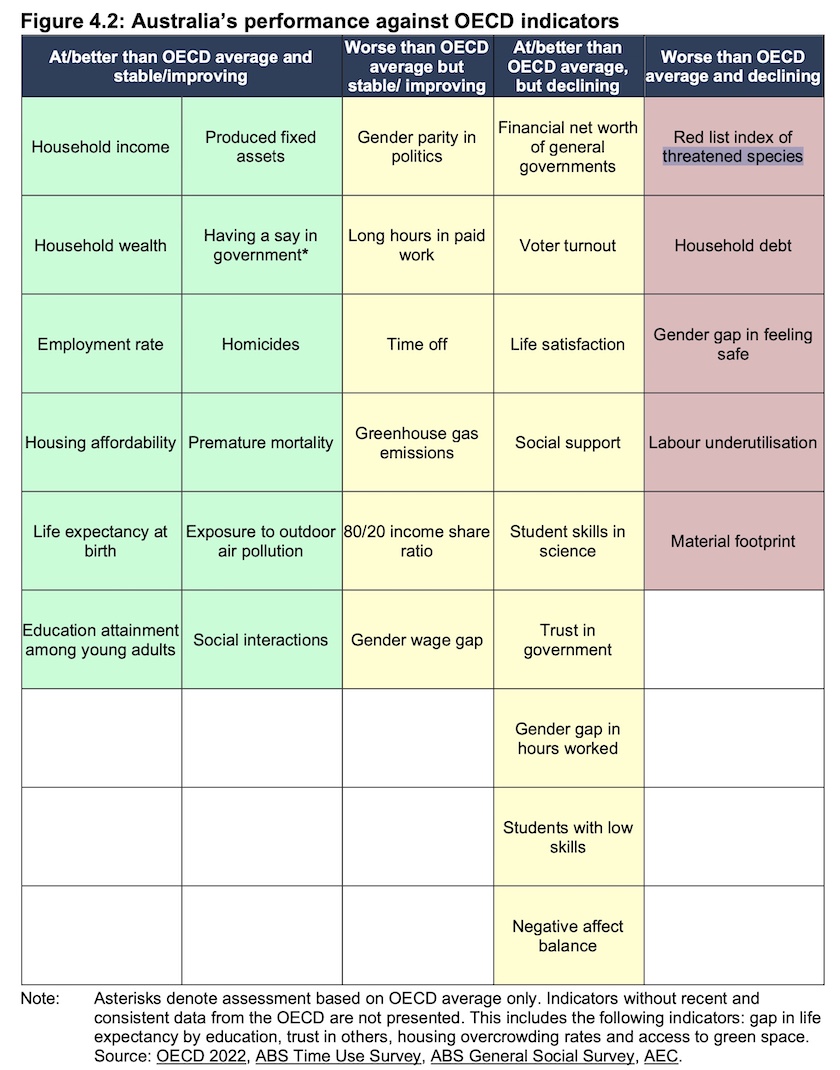

The “Measuring what matters” chapter of Budget Paper 1 is partly a discourse about the meaning of wellbeing indicators, acknowledging that there is work to be done. Such indicators become most meaningful after a few years as time series provide indicators of progress. For now we can look at some of our own indicators compared with those in other OECD countries, shown in the table below, copied from Budget Paper 1 (Page 130).

In the same chapter the government points out that some OECD indicators need to be interpreted with caution, and that we should have other indicators relating to our needs, such as outcomes for indigenous Australians.

In that table it’s surprising to see “household” wealth among the positive indicators, when much of that wealth simply relates to inflated land prices rather than anything more material. The chapter does acknowledge that the OECD’s metrics omit to cover housing affordability, but using the current market price of houses as an indicator of wealth is meaningless. The market value of one’s house may double or halve over a period, but its real value – its shelter, comfort and locational amenity – is fairly constant.

The table includes one direct metric about income distribution (the 80/20 ratio), but missing from this set of indicators is anything about the distribution of wealth, even though in Australia, as in many other “developed” countries, maldistribution of wealth is more enduring and is more significant in terms of people’s lifelong outcomes than the immediate distribution of income.

Energy prices – a nasty problem demanding a fix outside the budget

Unsurprisingly energy prices have emerged as a major issue. Hypocritically the Coalition is heaping blame on the government for not having lived up to its promise to ease the burden of electricity bills, even though in its last weeks in government it had suppressed forecasts that energy prices were bound to rise. The Coalition now seems to be blaming the government for not stopping Putin from invading Ukraine, and it is making no offer to support the government should it intervene on gas prices. Western Australia Premier Mark McGowan reminds the government and the opposition that when that state’s government introduced a gas reservation scheme in 2006, the Coalition, siding with multinational energy companies, was strongly opposed to the idea.

Giles Parkinson, writing in Renew Economy, has the clearest explanation for high electricity prices. It’s the price of gas: Wind and solar smash production records, but old fossils keep energy prices high.

Tony Wood of the Grattan Institute explains why energy prices are so high worldwide (Putin), and goes through options for Australia such as a windfall profit tax on gas companies and subsidies to consumers. He believes that the government will have to make some strong intervention in the market while prices are so high, and suggests the government, using powers it already has, set a regulated price for the domestic market, adequate for suppliers to make a reasonable return on funds employed: Can the govt do anything to stop 50% electricity rises?. (8 minutes) The ABC’s Brett Worthington believes that the Prime Minister is already considering such an intervention: Anthony Albanese considering electricity market intervention as federal budget forecasts surging prices. David Speers explains some of the political and contractual problems the government would encounter in capping gas prices, but they don’t seem to be insurmountable: Our most pressing economic challenge is soaring power prices, and the government needs simple solutions, fast.

Other comments – mostly positive

The Commonwealth budget always draws gigabytes of comment. I have chosen a few from some of the usual suspects.

Peter Martin has a summary of the budget’s main fiscal measures in The Conversation, including a useful consolidation of major cuts and new spending: Jim Chalmers’ 2022-23 budget mantra: whatever you do, don’t fuel inflation.

The ABC’s Michael Janda summarizes reactions to the budget. Economists are mostly positive about the budget because the government has avoided the temptation to spend the short-term revenue boost resulting from temporarily elevated commodity prices (Putin again). The opposition is scornful because it does nothing in the short term to address cost-of-living pressures: Treasurer's first federal budget welcomed by economists, but political reaction is frosty.

Cassandra Goldie of ACOSS, in an interview on ABC Breakfast, emphasizes the budget’s lack of support for those doing it toughest, including the unemployed. Benefits such as an increased supply of housing are some years down the track, and in the meantime people have to cope with rapidly rising electricity and gas prices. Goldie believes that governments should prioritize the welfare of those with low incomes: Budget foreshadows tougher times for households. (7 minutes)

Stan Grant points out that the budget does little to achieve a fairer distribution of income. He asks “When will the government start making the rich pay more to repay those who right now are going to hurt the most?” He understands (but does not sympathize with) the government’s strategy: if you give money to the poor they will spend it, driving up inflation. It’s unjust, however, that the poor are bearing the cost of containing inflation: The dirty secret at the heart of the federal budget — the poor will pay, and the government needs them to.

Laura Tingle looks at the budget as an exercise in political strategy. It’s about affirming Labor’s economic credentials, in an environment where sections of the media assert that Labor is poor at economic management, and where many people believe that to be so. “The budget is the work of a new government establishing its credentials as a serious budget manager by banking unexpected tax windfalls from high commodity prices”: This is a federal budget designed for “difficult decisions in difficult times” — and it needs to be.

The opposition’s and other politicians’ reply to the budget

Labor holds 103 seats in our Parliament, the Coalition 90, and they both get their half-hour to pontificate about the budget in Parliament and on national television, while the other 34 members of Parliament have to scrounge around for a public voice, even though most of them, unencumbered by a party platform, are likely to give a reasonably frank assessment. David Pocock, for example, long a supporter of raising more public revenue, is one who speaks honestly on the need to increase support for the poorest if we are to re-build a fair and decent society.

Peter Dutton’s reply to the budget had two main themes – the Coalition’s supposed economic competence and the cost of living focussing on energy prices.

On the first, the Coalition’s economic competence, it was back to their old story that they’re the better managers because they run tighter budgets – as if that’s all there is to economic management.

On energy, unsurprisingly he mentioned Labor’s election platform, in its Powering Australia document, envisaging a cut in people’s power bills by 2025, three years away, while talking about the 56 percent increases in electricity prices that could occur by 2023-24 (Budget Paper 1, Page 57). Although Dutton mixed the terms, the distinction between bills and prices is important, because there are policy measures that encourage better tariff structures to reduce peak demand, that help people invest in domestic-scale battery storage, and that help people reduce electricity use, even if prices are high. The Coalition is still talking about the ancient idea of “base load” power, rather than power systems that match varying supply and demand with a mixture of prices and technologies. And if he is so attached to a reliable power supply, why did he ridicule the AEMO’s Integrated Systems Plan which is specifically designed to smooth out supply from Australia’s geographically-dispersed renewable energy hot spots?

Also Dutton’s idea of using small nuclear power plants would do nothing to overcome what are really short-term problems. Labor has a plan that will surely work to reduce power bills, but its realization has probably been pushed back a couple of years. The nuclear option, even if the economic case passed muster (it probably wouldn’t), would take even longer to realize.

The rest of his presentation was disjointed, as if some party apparatchiks had inserted their favourite lines into his draft – radical gender theory taught at schools (really?), the horrors of multi-employer bargaining, a swipe at Labor state governments for Covid-19 restrictions, a proposal to raid superannuation to buy homes in the expectation that house prices will go on rising for the next hundred years, Australia’s British heritage (relevance?) and so on. Also he criticized the government for some of its budget cuts – generally reasonable criticisms – without revealing how the Coalition would finance these services. Rather he spruiked the stage 3 tax cuts that will allow us “to keep more of what we earn”.

To his credit, however, his approach was less aggressive than we have seen from some previous Liberal opposition leaders. He supported many of the government’s budget measures that the opposition had previously opposed, and he promised to cooperate with the government on some important issues, particularly to do with domestic violence. As a former cop he has seen the worst of it.

Summing up the budget

It appears that many people expected that in light of the economic and fiscal mess it inherited, the newly-minted Labor government would present a more reformist budget. In this budget, however, it has confined itself to reassuring financial markets of its fiscal intentions, to making appropriations for urgent electoral commitments, to putting a halt to some of the Coalition’s worst rorts, and to articulating its economic philosophy. Anyone familiar with the workings of government knows that even when there isn’t a change in government, the budget process takes six to nine months. That process would be well in train for the budget to be presented in May or June next year. The government will probably have to move well before then on gas and electricity prices: the budget isn’t the only vehicle for a government to implement its economic agenda.

All you ever need to know about inflation

According to advertisements in a 1960 copy of the Sydney Morning Herald, a Holden Station Wagon cost $2580 (£1290), a two-bedroom cottage in Balmain cost $7800 (£3900), a Hoover iron cost $21 (£10/10/0) and a small camera (Kodak Retinette) cost $45 (£22/10/0). An interstate three-minute phone call cost $1.50 (15 shillings).

Here is how the prices of similar items have changed:

- basic mid-sized car – now around $25 000, a 900% rise, although the car you buy now is safer, has lower fuel consumption, and probably lasts longer;

- small well-located Sydney house – $2 million, a 26 000% rise;

- iron – $40 for a basic model, a 90% rise;

- camera – $500 for a Panasonic Lumix camera, a 1 000% rise, but its picture quality is far superior to the Kodak Retinette’s, there is no charge for film, and in any case most people have a basic camera as part of their phone;

- phone call – free and not time-limited, a 100% fall, because most plans have a fixed annual price;

- basic computer – what was the equivalent in 1960?

Over the same period the consumer price index, the most commonly-used indicator of inflation, has risen by 1 564%, suggesting that a dollar in 1960 is equivalent to $15.64 in 2022. It’s a measure of the price rises of a “basket” of household goods. It doesn’t pick up the Sydney house because the land on which it sits, which comprises most of the price, is not “consumed”. But it does pick up changes in the cost of building a house.

These examples, with highly divergent price movements, provide a warning about the simplifications and assumptions behind statements about inflation being X percent, or that it is forecast to rise by Y percent. This is also a warning about simple notions that interest rates should be raised until X and Y come below some defined upper limit – three percent in recent Australian history. Prices move all over the place, some up, some down – that’s capitalism. Journalists and many other commentators vest too much authority in single-number “inflation” indicators, most often the CPI.

Greg Jericho of the Centre for Future Work has written what amounts to a textbook on inflation – Inflation: a primer – covering the theory of inflation and illustrating what has happened to prices and wages in Australia over the last twenty to thirty years. In a well-written explanation Jericho covers what most basic economic texts skip over. It is important for those whose job is to influence or implement economic policy to understand this theory, because too simplistic an understanding of what indicators such as the CPI denote can lead to bad public policy.

Even those who are reasonably familiar with economic theory would learn from his analysis of wages, inflation and productivity since the turn of the century. Until around 2015 productivity gains had been shared between profits and wages, but since then, including during the years of the pandemic, all productivity gains, and a little more, have gone to profits. We now have inflation not because wages have risen, but because companies have raised their prices. Yet we are using policy interventions that are designed to suppress wages. In his conclusion Jericho writes:

There is no evidence at all that a tight labour market, rising wages, or labour costs more generally have anything to do with the surge in inflation since the COVID pandemic. To the contrary, the evidence is clear that wages have had a dampening impact on inflation in this period: with nominal unit labour costs rising much more slowly than actual or target inflation, and real unit labour costs (and the labour share of GDP) falling to their lowest point ever. Recent inflation is clearly associated with a further expansion of business profits in Australia, to their highest share ever. Attacking inflation by aiming deliberately to increase unemployment and restrain wage growth even further, is a “blame-the-victim” policy that will only make workers pay even more for a problem they clearly did not create.

The most notable revelation in his work is a chart, towards the end, illustrating how the 15-34 year-old labour force has shrunk during the pandemic, and shows no sign of coming back to trend. Therein lies much of the explanation for labour shortages and consequent price rises. There are more intelligent ways to deal with this than choking the economy with higher interest rates.

Gareth Hutchens, writing on the ABC website, has a summary of Jericho’s findings: Growing profits and less power for workers. Who does inflation-targeting really serve?

The ABS confirms that inflation is high, but it’s not running rampant

The day after the budget the ABS released the consumer price index for the September quarter, revealing a quarterly rise in the CPI of 1.8 percent, which would equate to an annualized rise of 7.4 percent.

It’s a little less scary than it appears at first sight. The equal biggest quarterly rise – 3.2 percent – was in housing, reflecting rising costs of house construction, but the ABS notes that prices started to ease over the quarter. Rents, however, are rising steeply.

That 3.2 percent was matched by a rise in food prices, including a 4.5 percent rise in fruit and vegetables as a result of floods.

The “trimmed-mean” inflation measure, which disregards large price rises and falls was still 1.8 percent for the quarter.

Notably the ABS finds that there have been higher price rises for non-discretionary items than for discretionary items. The Reserve Bank should take note, because, almost by definition, there is less income elasticity for non-discretionary consumption. Using interest rates to reduce people’s income as a means of controlling inflation for such items just doesn’t work, because they have to go on buying them. A cleverer means of controlling inflation is needed.