Other public policy

Putting the public interest back in public service

“In some departments, the public service became more like an administrative service to ministers, with core work like policy development being shipped out to consultants”.

That’s a quote from Katy Gallagher’s speech on the government’s reform agenda for the public service.

The Albanese government has inherited several problems from its predecessor’s deliberate policy of running down the public service.

First, and most easily measured, is the cost of obtaining policy advice from consulting firms. Because the Coalition imposed staff ceilings on the public service, departmental managers had no alternative than to go to consultants for work which would have cost less had they been permitted to take on staff to do the work in-house. Not only are consultants’ fees much higher than the cost of in-house work, but there is also the cost of contract management when hiring outsiders.

Second is the quality of the work done by consultants, who may have little understanding of the difference between the profit-maximizing environment of the private sector and the more complex economic mandates of the public sector. Because of market failures and requirements to observe procedural and distributive justice, the work of the public sector is fundamentally more complex than the work of the private sector. As Herman Leonard of the Harvard Business School said, “the hard jobs are left to the public sector”. Also while experienced middle-ranking public servants accumulate deep understanding and knowledge of policy areas, staff in consultancies tend to be generalists: they have to be because they don’t know where the next contract is coming from.

Third is that fact that consulting firms often embody an ideology that John Halligan of the University of Canberra called “private sector primacy”. That is, regardless of the evidence and argument for a function being in the public sector, the assumption is that it should be privatized or contracted out, even if that involves waste and corruption. Throughout the world consultants have provided cover for right-wing governments to privatize health care, education, electricity, and other functions that have given massive returns to cronies with close government connections. For just one of many examples, see Michael Forsythe and Walt Bogdanich McKinsey charged in South African corruption case in the New York Times, which is about a bunch of international consulting firms and their behaviour. Gideon Haigh, writing in Inside Story, has a review – Amorality for hire – of Forsythe’s and Bogdanich’s book When McKinsey comes to town.

Fourth, hinted at in the quote at the beginning of this piece, is what could best be described as systemic corruption of the public service. Jack Waterford has a piece in the Canberra Times: Katy Gallagher's vague ideas and clichés won't fix the public service (unfortunately paywalled), in which he identifies the “big problem”:

… the system of government Labor has inherited … a debilitated public service which had learnt bad habits, and which had watched, in some cases helplessly as uncontroversial concepts of governing in the public interest fell apart.

Gallagher is clearly aware of this problem, but is her idea of “asking the APS to create a clear and inspiring purpose statement” adequate? Surely public servants need to be bound by a code of ethics so that when they are directed to act against the law (as has been the case with Robodebt), or to lie in press statements drafted for ministers, they should be obliged to refuse such directions. Whistleblower protection is not adequate to protect the public against systemic corruption.

In criticizing Gallagher for delivering a speech laden with bad ideas and clichés, Waterford (inadvertently perhaps) illustrates one of the very problems the government is trying to expose. The speech would probably have been written by public servants, who, over many years, serving governments that did not wish to communicate frankly with the public, have learned such a style.

The core of Gallagher’s speech is about restoring the public service’s capability. Just how the government intends to go about this is unclear, and, as Waterford suggests, the writers of her speech may have underestimated the size of that task. Waterford notes that the 2019 Thodey Review of the public service, which seems to have influenced the present government’s thinking, was long on generalities (“managerial clichés”) and short on specifics.

It’s not clear from Gallagher’s speech whether the government is seeking to set up its own consulting service under the Australian Public Service Academy, which would become another generalist consultancy outfit (ready to be sold to McKinsey when a hard-right government is elected), or if the government’s desire is to improve the capabilities of public service departments when she says that the government intends to conduct capability reviews of departments and agencies.

Anyone who wants to see a strong public service providing well-considered and independent advice to government would agree that strengthening its capability is important. But that’s a major task. Many senior managers, conditioned by serving Coalition governments for 20 of the last 26 years, and having worked under a Public Service Act amended in 1999 to deliberately politicize the public service, see their duties through the narrow perspective of carrying out their minister’s directions, rather than the broader task of helping a government implement its policies in a way that aligns with the public interest and complies with the law. They have little respect for their subordinates’ capabilities, other than their ability to follow directions: in such an organization people with analytical or policy expertise are bloody nuisances.

The government could do well to go beyond its usual process of hiring graduates and explore possibilities such as exchanges with universities, state public services, and foreign public services.

Domesticated regulators

As far as many businesses are concerned, a tame regulator who doesn’t bother business too much is a good regulator.

In the Saturday Paper – Bankster’s paradise – John Hewson calls for the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC), the Australian Securities and Investment Commission (ASIC) and the Australian Energy Regulator (AER), to be more assertive. Under the Coalition government the regulators were encouraged to go easy on businesses. They were allowed to fall asleep at the wheel, and to neglect their duty to make competition policy work in the interests of consumers and in the interest of supporting a generally more dynamic economy.

Hewson is particularly critical of ACCC for its “tolerance of the concentration of market power in key sectors, and of privatisation principally for revenue rather than efficiency”. (Does privatization ever generate efficiencies that cannot be achieved by competent public sector managers?)

These regulators have developed a risk-averse-prosecution-averse culture – a culture that does not support those who try to bring corporate misconduct to public attention. As a warning to the government about this culture Hewson writes:

The Albanese government can go only so far in claiming it’s a consequence of the Coalition in government when successive prime ministers did little about it. If this government now similarly fails to act, it will soon be their problem, for which they will be held entirely accountable.

Ending violence against women and children will take more than fine words

It would be hard for anyone to disagree with the aspirations in the government’s National plan to end violence against women and children 2022-2032. All aspects of violence are covered – including murder, rape and coercive control. The report covers four areas where public policy can influence outcomes for women – prevention, early intervention, response and recovery. Specific plans, which will include clear and measurable targets, are to come later.

The ABC’s Nour Haydar has a short summary of the plan, including a 5-minute interview with Social Services Minister Amanda Rishworth.

The plan acknowledges the special needs of women in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, for whom a specific national plan is proposed. But there is only passing reference to the special needs of women from cultural backgrounds in which ideas of family honour and interpretations of religious codes lead to mistreatment of women. Nor, in spite of the inclusion of children in the title, is there much attention to violence directed against children, even though Australia is in a minority among “developed” countries in allowing parents to subject children to corporal punishment.

Anastasia Power of RMIT University, writing in The Conversation: A new national plan aims to end violence against women and children ‘in one generation’. Can it succeed?, notes that the plan is mainly concerned with physical violence. But “other forms of violence that are disproportionately directed at women and girls receive little attention – such as online forms of harassment and abuse, labour exploitation, sexual exploitation, and abuse of children.”

The plan is ambitious, but the extent to which governments in a democracy can change behaviour is limited, and governments are even more limited in their capacity to change cultures within which behaviour is embedded.

Governments are not entirely constrained, however, provided they are willing to allocate resources to dealing with the problems, and to take a lead in encouraging and discouraging certain behaviours. The report mentions specifically the need to provide more housing for women and children fleeing violence. That’s expensive. The report acknowledges the influence of gender stereotypes, but it’s disappointing to find no mention of the absence of legislation that would outlaw gender-segregated schools and clubs, and no mention of society’s tolerance of sports such as boxing and football that valorise male violence.

What gender is your plumber?

In case we believe there has been good progress towards gender equality in the workplace, Michael Coellli, writing in The Conversation, reminds is that although Australian women are more educated than men, there are big gender divisions in work. There is a 1.0 percent probability that your plumber will be a woman, and a 97.6 percent probability that your child’s early childhood teacher will be a woman.

Using his estimates of the “Duncan index of dissimilarity” (he explains it clearly), I have done a simple linear extrapolation of progress over the last 55 years to calculate that men and women won’t be equally represented across all occupations until the year 2316.

In education men and women are on different pathways. Many more women than men are graduating with bachelor’s or higher degrees: only among Australians older than 65 are there more men than women with degrees. For certificates and diplomas, however, men dominate, but among younger age groups there are early signs that women are catching up.

One in eight Australians live in poverty

That’s the main finding of an ACOSS report Poverty in Australia 2022: a snapshot, where the poverty line is defined as 50 percent of median income for a person or couple in the same family situation. Even more noteworthy than its finding that 13 percent of Australians live in poverty is its finding that 17 percent of children live in poverty.

For a brief period, in the June quarter of 2020 when income-support payments were boosted during the worst of the Covid-19 restrictions, the poverty rate fell to 12 percent, having been 15 percent in the preceding quarter.

ACOSS’s research is based mainly on the 1999-20 period. Since then the labour market has improved, but prices, particularly rents, have risen steeply, and CPI-adjustments to government benefits have probably been inadequate to sustain standards for people living on those benefits.

Its detailed findings on the adequacy or otherwise of government benefits are in a table (Page 24) comparing various family situations with unemployment benefits (“Jobseeker”) and pensions. Pension payments are fairly close to the poverty line, but for people with children, unemployment benefits are a long way under the poverty line.

A look inside Australia’s “most corrupt” industry

Casinos have been in the news but we shouldn’t take our eyes off the less glamorous part of the gambling industry – poker machines.

In his Policy Post Martyn Goddard pulls together research on gambling to demonstrate (once again) that poker machine operators deliberately target the poor and those at most risk of gambling addiction: Profit from pain: how our most corrupt industry really works. Heavy gamblers’ losses provide the cash flow that keeps these venues afloat.

He takes us into the psychological minefields laid by poker-machine owners in order to create gambling addiction.

He also reminds us of the misdeeds at the top end of town, in casinos involved in money laundering.

Goddard wrote his contribution before the operators of Sydney’s Star Casino, following revelations of criminal activity, were directed by the Casino Commission to say three Hail Marys and promise to be good little boys in the future, before going back to running their business. You can hear what the regulator, politicians and others have to say about the decision on ABC News: Star's Sydney casino licence suspended from Friday but doors will remain open. The rationalization for not closing it is that thousands of people would lose their jobs.

That’s a lame reason for keeping it open, but the gambling industry keeps trotting it out. Imagine if a government were to say it wasn’t going to repair dangerous roads because car crashes kept nurses, surgeons and crash repairers employed. Employees of these casinos have chosen to work in an industry tarnished with findings of criminal activity, and in any event there is a severe labour shortage in all sorts of industries. Closing Sydney’s casinos and poker machine venues would give them opportunities to find work doing something useful, which must surely be more satisfying than helping people get fleeced. As Elise Bant of the University of Western Australia says “We don’t want employees frankly operating in a criminogenic environment: that’s not good for them, not good for society”.

Health policy

Are health and aged care payments being rorted?

An investigation by journalists from the ABC, The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age, based at least in part on a PhD thesis by Margaret Faux, has led to claims that up to $8 billion a year may be leaking from the Medicare budget because of fraud, incorrect payments and errors. A summary of the claims is on the ABC website – Expert estimates $8 billion a year lost to Medicare fraud and waste – and in an article in the Sydney Morning Herald – “Medicare is haemorrhaging’: The rorts and waste costing taxpayers billions of dollars a year. The ABC has two television stories so far on this investigation: Could $8 billion a year be lost to Medicare fraud and waste? and How cosmetic surgeons are taking advantage of Medicare.

The Australian Medical Association has a transcript of an interview on its site, in which it suggests that those making claims of fraud and overpayment may have some conflict of interest.

In a separate investigation Rick Morton, writing in the Saturday Paper, reports that nursing homes have been advised to avoid “high-needs” patients. Although his investigation appears to be thorough, it is not clear whether the problem is systematic rorting or a poorly-designed payments system with perverse incentives – a problem easily fixed. Some of the health department’s payment systems seem to have been designed by people with little understanding of accounting or managerial economics.

One point is clear from Morton’s article, however: many nursing homes are struggling.

There will always be a certain amount of fraud in any payments system with millions of small claims and in which the customer does not always see the bill. The task for policy makers is to balance compliance costs against costs of fraud. When there are allegations of widespread fraud, however, as is the case in the present allegations, there is a more serious challenge, because once providers believe fraud is the norm, they are mugs if they do not engage in fraud themselves – the essential “prisoners’ dilemma” situation described in Catch 22. It’s not about morality: it’s about incentives and survival. That’s why, for the sake of public confidence and the concerns of conscientious providers competing with fraudsters, the government has to take a strong and public stance. A video clip of cops turning up at a South Yarra or Hunters’ Hill mansion to arrest a fraudster sends a re-assuring message to all who see health care as an essential service rather than as a honeypot for thieves.

Also while journalists and others should always be on the lookout for fraud, they should also be aware that when there are competing private and public interests to provide services, there is often an ideological incentive for some to claim that the publicly-administered system is rotten.

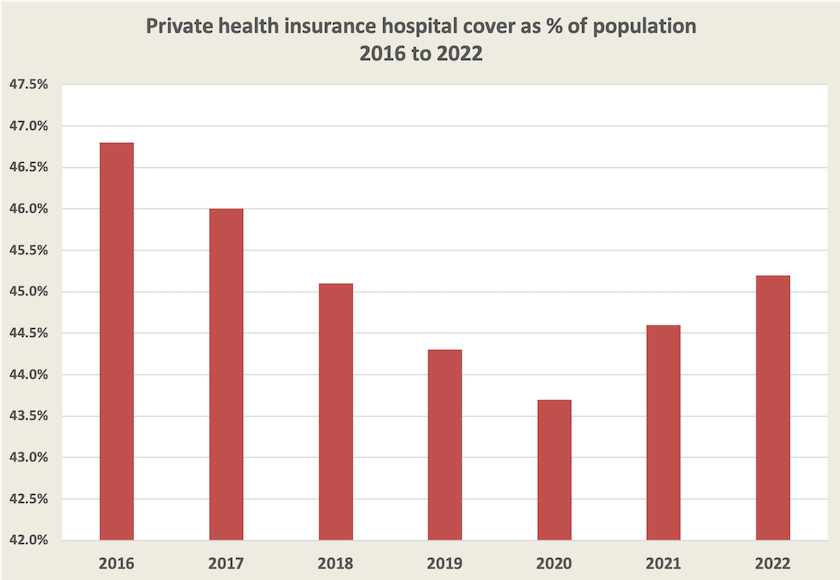

Private health insurance making a stealthy comeback

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority’s report on private health insurance for the year to June 2022 shows that after many years of falling membership, people are once again taking up private health insurance.

At a time when there is stress on public hospitals, both for funding and resources, and a backlog for elective surgery, this increase in PHI membership should be of concern to governments and public hospital administrators, because PHI is a mechanism to encourage queue jumping, and a diversion of resources from public to private hospitals. Unless the government removes some of the ill-considered incentives for people to hold PHI, public hospital waiting lists and staff shortages could worsen as a result of higher PHI membership.

The PHI lobby has consistently argued that without PHI the “private system” would be put under stress. Covid-19 has given governments the opportunity to reveal the basic flaw in that argument, because many state health authorities contracted private hospitals to provide services for public patients, which they did very well, demonstrating that private health care providers do not have to be dependent on a high-cost private financial intermediary for their survival.

Covid-19 – still around but probably falling

As standards for reporting Covid-19 slacken off (they were never highly reliable), about the only reasonably consistent indicator of the pandemic’s incidence is the number of deaths attributable to, or associated with, Covid-19, with the qualification that there is 3-4 week lag between infection and death.

Globally and in the EU there has been a small increase in Covod-19 deaths in the first half of October. Australian figures from the Health Department still look promising. Cases and hospitalizations are falling slowly, and deaths have fallen steeply – although at 12 a day, or 0.5 per million population, Covid-19 is still a significant killer.

One reader has suggested that the weekly Flu Tracking report gives a first-order indicator of Covid’s incidence. It can be a useful indicator because it covers “respiratory illness”, manifest in a fever or cough, which may be Covid-19, influenza or other respiratory conditions. Past reports have shown a reasonably strong correlation between Flu Tracking figures and Covid-19 cases. There is little to be interpreted from the absolute number of Flu Tracking reports, because it comes from a self-selected non-stratified group, but it is a consistent cohort, which means its trends are meaningful.

The Flu Track report to 16 October shows a steep fall from the June surge in cases. There is a small uptick in the latest week, but this may be a statistical blip.

Covid-19 – a policy review

On Thursday the media splashed stories about an “independent report” claiming that Australia’s Covid response was “overreach” and had worsened inequalities.

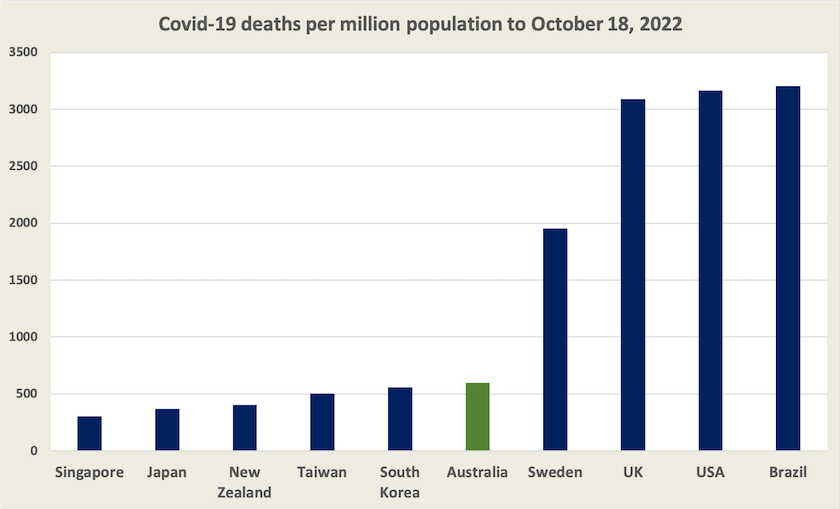

Before reading the report, you may care to consider the graph below, drawn from WHO data, comparing Covid-19 deaths per million population in “developed” Asian countries, including Australia, which took strong measures to deal with the pandemic, with four countries that took a more “let it rip” attitude and had the world’s highest recorded deaths from Covid-19.

You may also consider the way the pandemic was understood in the first half 2000, until the world was surprised by the speed of vaccine development. It was a deadly disease, killing up to one in ten people who contracted it.

The report Fault Lines: an independent review into Australia’s response to Covid-19 is available on the Paul Ramsay Foundation website. Michelle Grattan has a short descriptive summary in The Conversation.

It identifies many administrative failings by governments, Commonwealth and state, including those that led to avoidable deaths in aged-care facilities, but it is only mildly critical of the Commonwealth’s delay in ordering vaccines. Its most important contribution is to expose the inequitable way in which the burden of coping with Covid-19 has been distributed.

Its most controversial aspect is the suggestion that governments may have overreached in containing the virus. It states that “there were too many instances in which government regulations and their enforcement went beyond what was required to control the spread of the virus, even when based on the information available at the time”. It also states “It is now obvious that we overestimated mortality and underestimated the collateral damage of the actions taken to stop the spread of Covid-19”.

The thinking of its authors, in making such statements, is revealed in the last of its five “lessons”, where it states “The response to Covid-19 produced sharp trade-offs between health, social and economic outcomes”.

That’s an explicit statement of the assumption that there is some trade-off between “the economy” and “society”, and between “health” and “the economy”. Logically it’s a category error: “the economy” is a set of arrangements to serve social ends, not some entity in its own right that sits alongside or even above society. (See an Inside Story article on this point, written in May 2020.) Turning back to the graph on deaths, how many people would have chosen the Covid outcomes of Brazil, the UK and the USA over the outcomes in those countries that prioritized the safety of their citizens? Why did the people of Western Australia, perhaps the state most severely affected by Covid-19 restrictions, re-elect its government with a thumping majority?

Come to think of it, reflecting on the fortunes of Brazil, the USA and the UK, none of them have performed very well on economic outcomes either.