Public policy: public finance

We need to repair our public revenue

Successive governments have been ignoring a basic unsustainability in our public finances: we don’t collect enough taxation.

In an ABC discussion on taxation – How much tax is enough? – on the ABC’s The Money program, Richard Aedy summarised the problem: we expect to enjoy European standards of public services while paying American levels of tax.

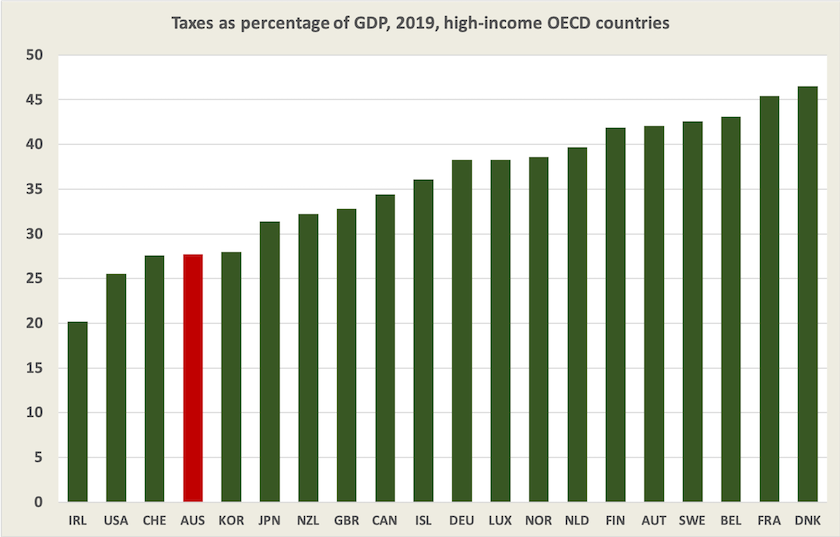

The chart below, derived from OECD statistics, shows Australia’s taxes in relation to other high-income OECD countries. At 28 percent of GDP (Commonwealth plus state taxes) we are down near the bottom.

The three countries ranking below us are Switzerland and Ireland, both tax havens, and the USA which has been running budget deficits of around 3 percent of GDP for most of this century, a profligacy that only that country can enjoy because of the global status of its currency. If it collected enough taxes to cover its expenditure it may even move up ahead of Australia.

In discussing the coming budget Treasurer Chalmers has been upfront about the demands placed on the Commonwealth to fund health care, the NDIS, defence and other services. In addition there is the Covid deficit: as interest rates rise the cost of servicing that deficit will rise.

In the pre-election period, however, Labor largely ruled out any increase in taxes, apart from some possible changes to taxes on multinationals. As we explained in last week’s roundup, the only other revenue option still on the table seems to be some modification of the already-legislated income tax cuts, although that is unlikely to appear in next week’s budget. As John Quiggin points out, writing in The Conversation, in sticking with tax cuts divorced from reality, Labor is left with a hard choice, that choice being to cut services or to let debt grow, at least in the short term.

Other independent voices are calling for the government to confront the problem of our low tax base and to look at tax reform more broadly than tweaking income taxes. In a 22-minute interview with Michelle Grattan, recorded on The Conversation, former ACCC chair Rod Sims puts the case for tax reform. Tim Colebatch, writing in Inside Story, says it’s time to talk about tax. Independent MP Allegra Spender has called for a widening of our tax base.

Although these advocates for reform come from different backgrounds and shades of ideology, there is much in common in their messages. One strong point is that we need a grown-up public discussion on taxes, and to have that discussion we have to dispel three widely-held beliefs.

The first belief is that in Australia we burdened by high taxes and must therefore constrain the amount of taxes we collect. Without any supporting argument or justification, the Coalition when in office set a Commonwealth taxation ceiling of 23.9 percent of GDP. As the Australia Institute points out, it’s an arbitrary figure. (A Treasury paper on tax-to-GDP ratios reveals that this was the average tax collected over 2000-01 to 2007-08. Somehow it has assumed a salience, similar to Douglas Adams’ 42.)

As we pointed out at the beginning of this piece, at 28 percent of GDP our taxes are much lower than those in other “developed” countries. Another 7 percent of GDP would put us among countries like Canada and Germany whose taxes are around 35 percent of GDP. As a back-of-the-envelope calculation, based on our GDP of about $2 trillion, we can estimate that each one percent increase in taxes brings in another $20 billion of public revenue. To put that figure in perspective, the stage 3 tax cuts would cost around $18 to $24 billion a year. Another 7 percent of GDP is around $140 billion a year.

Fortunately, in spite of pre-election goading by then Treasurer Frydenberg, Chalmers has not committed Labor to retain that “bizarre” 23.9 percent Commonwealth cap, as Peter Martin writes in The Conversation: Australia needs an honest conversation about tax and budgets. Martin believes Chalmers is ready for a serious discussion about tax.

The second belief, perpetrated by political parties on the right, is that high taxes impede economic growth. The only trouble is that there is no evidence or coherent argument to support that belief. In all immodesty I refer to the work Miriam Lyons and I did for our 2015 book Governomics: can we afford small government?, showing that among “developed” countries there is no relationship between tax levels and economic growth, a point easily confirmed by updating the data we used in that book. In fact if an inadequate revenue base constrains public expenditure on infrastructure, education and other economic services, low taxes can impede economic growth. Australia stands out as a country that combines low taxes with low per-capita economic growth.

The third belief, or at least a commonly-held concern, is an obsession with income taxes. As the volume of media articles about the stage 3 tax cuts confirms, we are unduly focussed on income taxes. Compared with other countries Australia is heavily dependent on income taxes, partly because we do not collect much tax from other sources.

Few people, other than those on the loony libertarian fringe, would argue against a progressive income tax, but all that a progressive income tax, or, for that matter, our selective GST can do, is to help smooth out inequalities in income. That may read as a statement of the obvious, but as Thomas Piketty and others point out, inequalities in wealth have come to dwarf inequalities in income, and while inequalities in income may even out to a certain extent over people’s lifetimes, inequalities in wealth have their own self-reinforcing positive feedback mechanisms that result in them becoming wider over time.

That is one reason we should be looking at other sources of taxation to complement personal income taxes, and those who have been calling for a wider base have plenty of suggestions (many of which were in the 2010 Henry Tax review). They include:

- forms of resource-rent taxes: in comparison with other countries with natural resources we get far too little benefit from the raw materials we dig up and export;

- a carbon tax, which would not only improve resource allocation but would also provide funds for necessary pubic investments to help de-carbonise our economy, before (hopefully) in time there is no more GHG pollution to tax;

- a super-profit tax on fossil-fuel exporters when they take advantage of high world prices: it would not distort investment decisions because the industry does not have a long-term future;

- ending or reducing tax breaks for so-called “self-funded” retirees;

- a higher GST;

- inheritance taxes;

- a land tax.

These last three warrant particular comment because they all go some way towards taxing wealth.

Many people point out that a GST is regressive, and that is easily demonstrated in basic economic theory. But it is a tax that the wealthy cannot really avoid. Also, in our taxation arrangements in Australia, because GST revenue all goes to the states, it funds schools, hospitals and community protection which comprise more than half of state budgets and are highly re-distributive in their effects. Many Australians rightly urge our governments to follow the public revenue lead of Nordic countries, but rarely do they point out that Denmark, Norway and Sweden all have a 25 percent consumption tax.

Inheritance taxes are specifically directed at wealth. Their only shortcoming is that they are easily avoided, particularly by those with large amounts of financial wealth, who can arrange their affairs so as to minimize tax. That means they tend to be paid mainly by those with modest means.

Land taxes are another revenue source. Rod Sims mentioned that Australians are sitting on $5 trillion worth of real estate, and a drive around a capital city or a browse through a real-estate website confirms that a land tax would be progressive. Based on Sims’s guestimate a 0.2 percent land tax would raise about $10 billion a year. Local governments are already collecting land taxes in the form of municipal rates, and some governments, notably the ACT and New South Wales, are moving to land taxes to take the place of property transfer taxes (which are generally regressive). Piketty’s critics correctly claim that wealth taxes are hard to collect, but at least governments can tax the land component of wealth because it can’t be carted off to a tax haven: it’s the ultimate immobile asset. We covered the Grattan Institute’s thoroughly-researched work on land taxes in theSeptember 24 roundup.

Essential poll on taxes

This week’s Essential Report, apart from one question about Albanese’s approval rating (still at rock star levels) is about taxes and public expenditure – or at least the personal income tax cuts.

Australians are pretty much in a 50:50 split as to whether the Albanese government, or any government, should break an election promise if circumstances change, the political issue hanging over the stage 3 tax cuts. On this question older respondents tend to be more pragmatic than younger respondents: presumably they have seen many governments break promises without serious consequences. This question also reveals more than a little hypocrisy, because Coalition voters are far more emphatic than Labor voters in their idea that the government must adhere to its election promises. How soon fades the memory of Tony Abbott!

On more open-ended questions about the tax cuts there is a large proportion of “don’t know” responses, confirming the need for better community knowledge about taxes, but in general there is strong support for retaining progressivity in the income tax system, and for the specific proposition that “maintaining funding for education and health is more important than reducing taxes for people earning more than $200 000”. Coalition voters are the only group agreeing with the idea that “the best way to attract and keep talented people in Australia is to reduce taxes for individuals on high incomes”.

Infrastructure – impressive announcements of unimpressive allocations

Once were nation-builders – Wodonga to Cudgewa railroad, constructed between 1889 and 1919

The government has made a pre-budget announcement of a $9.6 billion investment in infrastructure. Before anyone gets too excited, it should be noted that it’s a small amount in the context of the backlogs in our urban and rural and transport infrastructure, and there is no time commitment. The amounts announced bear little relationship to the size of different states’ economies or rates of growth. They are:

- New South Wales $1.0 billion

- Victoria $2.6 billion

- Queensland $1.5 billion

- South Australia $0.7 billion

- Western Australia $0.7 billion

- Tasmania $0.7 billion

- Northern Territory $2.5 billion

- Australian Capital Territory – spared an announcement.

The hugely disproportionate Northern Territory allocation is largely explained by $1.5 billion for the Middle Arm Sustainable Development Precinct – a misleading name in view of the prominence of offshore gas and carbon capture and storage in the project. In fact it’s misleading to allocate such funding under the infrastructure budget, because it’s a facility for one industry: it should be classified as industry assistance. If the Greens succeed in their attempt to block the project they will make $1.5 billion available for useful infrastructure and save a government in the not-too-distant future from the embarrassment of a stranded asset.

Victoria gets the lion’s share, mainly for Melbourne’s Suburban Rail Loop, a $30 - $35 billion project that is not expected to be completed until 2035, and for which at present there seems to be nothing more tangible than a website. Could this announcement have anything to do with the state election next month?

The New South Wales announcement refers to “high speed rail”, but it is only “to start corridor acquisition, planning and early works”, for a possible short line from Sydney to a little past Newcastle.

Although projects announced in the allocations may be worthwhile (benefit-cost ratios are not revealed), the reason for involvement by the national government is not clear. Why should the Commonwealth be funding roads in northwest Sydney or in southern Adelaide – which should rightly be the remit of state governments – when there are glaring gaps in interstate connections? The Melbourne - Adelaide road is mainly two-lane, Canberra is connected to the Hume Highway towards Melbourne by a dangerous two-lane road, and at present parts of the low-lying Sydney-Adelaide and Melbourne-Brisbane roads are flooded.

Minister King seems to be carrying on the practice of the Morrison government – using cut-and-paste announcements for the media to cover for a lack of substance, and hoping no-one looks too closely at the figures.