Public policy

The IMF’s gloomy outlook

There has been a fair amount of media cover of the IMF World Economic Outlook with its gloomy economic outlook, particularly for the USA and Europe. That gloom is about inflation – or more specifically about the economic consequences of higher interest rates that monetary authorities are imposing in order to rein in inflation. For our region – “Advanced Asia” (including Australia) – its outlook is comparatively positive.

Its policy prescriptions are summarized in its introduction:

Global inflation is forecast to rise from 4.7 percent in 2021 to 8.8 percent in 2022 but to decline to 6.5 percent in 2023 and to 4.1 percent by 2024. Monetary policy should stay the course to restore price stability, and fiscal policy should aim to alleviate the cost-of-living pressures while maintaining a sufficiently tight stance aligned with monetary policy. Structural reforms can further support the fight against inflation by improving productivity and easing supply constraints, while multilateral cooperation is necessary for fast-tracking the green energy transition and preventing fragmentation.

That statement includes the IMF’s predictable emphasis on fiscal and monetary tightness, but at least it acknowledges supply-side constraints and the need for a green energy transition. Much of what it classifies as “inflation” is in line with strict economic terminology, but it could be better described as a set of price shocks, particularly energy and food prices, which, by the IMF’s own calculations, will fall back. It is questionable whether traditional fiscal and monetary tightening, the instruments applied to quell demand-side inflation, are the right instruments to apply in the present situation.

On a quick flip through this document its support for carbon-pricing stands out. On a carbon tax it states:

Recent macro empirical studies have assessed the impact of carbon taxes on GDP using cross-country panel regressions and have found no evidence that carbon taxes have led to reductions in activity.

So why is our government, so burdened by the “trillion dollar debt”, not levying a carbon tax?

The Reserve Bank’s monetary projections and its observation on capitalism’s demise

The Reserve Bank’s October Financial Stability Review, which follows its decision to raise the cash rate target by 25 basis points, acknowledges that some households will experience loan payment arrears.

Was it unaware of this risk over the ten years from 2012 when it kept pushing down nominal interest rates, encouraging borrowing and fuelling an unsustainable housing boom?

Most media attention has been on the RBA’s predictable monthly interest-rate decisions. Less attention has been paid to an address by the Bank’s Assistant Governor (economic), Luci Ellis: The Neutral Rate: The Pole-star Casts Faint Light. This is a thoughtful and well-researched contribution to our understanding of monetary policy and of the trajectory of capitalism in Australia and the world.

In part it’s about the difficulty monetary authorities experience in setting a real interest rate, because the real rate is the geometrical difference between the nominal rate (as set and promulgated by the central bank), and expected inflation. The bank has the latest figures on inflation, but that is a measure of inflation a few months in the past, and the bank has to estimate what inflation will be in the near future. The task is particularly difficult because the bank’s decisions will affect inflationary expectations. That’s a well-known issue, covered in basic macroeconomic units: Ellis’s explanation will be of help to economics students but unfortunately it doesn’t seem to have grabbed the attention of journalists.

The other part of her presentation is about the “neutral rate” – the interest rate that is “neither contractionary nor expansionary”. As monetary authorities have experienced, it is hard to ascertain, but once the noise is smoothed out, it is clear that it has been falling over the last 30 years in most “developed” economies, including Australia.

One interpretive summary of her address is that the era of gung-ho capitalism with easy returns is behind us. Corporations and financially wealthy individuals, conditioned by decades of high returns, rather than making real investments, have responded to monetary stimuli by pushing up the price of existing assets. We are all going to lower our expectations about investment returns.

A Marxist would have an even simpler interpretation: capitalism is in its dying days.

Tax cuts – no need to rush with a repeal

“Do you believe the Albanese government should proceed with the promised tax cuts?”

Pollsters have been putting that question, or minor variants of it, to electors. As David Crowe writes in the Sydney Morning Herald, it depends on how the question is framed.

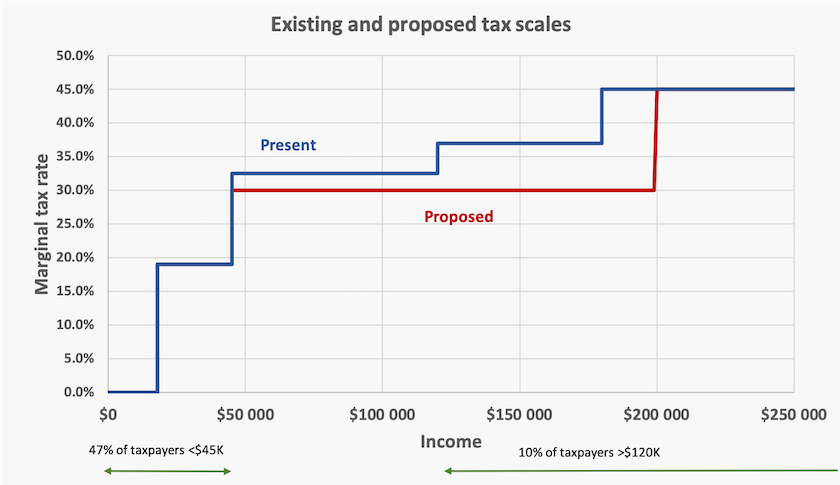

To understand the issue, it’s worthwhile considering what the tax cuts involve, as illustrated in the diagram below. The present scales are in the blue line and the stage 3 scales are in the red line. (For those who seek more precision than reading off a graph The Guardian has an article providing the figures on income thresholds and marginal rates.)

In simple terms, everyone with an income above $45 000 would get a cut. That probably sounds appealing to anyone with a full-time job paying above the minimum wage, but from a broader perspective, the median taxable income (2019-20) is only $48 000. The tax statistics relate only to the 15 million people who lodge tax returns, there being others, such as some pensioners, who do not lodge returns. Therefore they overstate people’s average and median incomes. At least half of adult Australians would get no relief from the stage 3 cuts.

The present 32.5 percent rate would drop to 30.0 percent, and the 37 percent rate, which presently cuts in at $120 000, would be abolished. Anyone with an income between $45 000 and $120 000, a range covering most full-time wage and salary earners, would get a small tax cut. That is really political spin to sell the cuts, because even at the top of this range, $120 000, the cut would be only $1 875, or 1.6 percent of income.

The main beneficiaries of this change would be those with incomes above $120 000, or 10.5 percent of taxpayers.[1]

The other change would be that the point at which the 45 percent marginal tax rate applies in is raised from $180 000 to $200 000. This would be of benefit to those 3.6 percent of taxpayers with incomes above $180 000.

Armed with those figures, and the knowledge that the cuts are not due to take effect until 2024-25, perhaps people could make some reasonably well-informed responses to surveys, at least in relation to their individual situations.

David Crowe has an article based on some detailed questions, on which a sub-editor has attached the headline: Voters back spending cuts over tax increases to fix budget but that’s too simple a summary. It’s worth looking at the responses to the questions, even if they do no more than confirm what is generally found in surveys of this nature. Not many people want to pay higher taxes, but they don’t want spending cuts either, these opposing preferences being reconciled by a hope to see the economy grow so that neither will be necessary. Only Coalition voters really stand out as strongly in favour of spending cuts. Respondents were also asked where spending cuts should be made if there were no option – health, NDIS, aged care or defence? Defence loses out badly in this test of public opinion. Does this reflect a public perception that our security situation is much safer than the hawks in government see it, or a realization that the present government has inherited a defence procurement mess?

Although the main issue relates to income tax cuts, the survey also asked about other means to raise tax revenue. Increasing corporate tax rates, and abolishing breaks for investment properties and capital gains were seen as preferable to abolishing the stage 3 cuts.

The Australia Institute also has surveyed people on the stage 3 tax cuts, and has findings broadly similar to those Crowe reports: 41 percent of respondents believe they should be repealed; 22 percent believe they should be kept; and 37 percent don’t know or are unsure.

Counter to what some may expect, those with high incomes are even more in support of repealing the cuts than those with low incomes. One Nation supporters, who are surely representative of those with the lowest income, are quite strongly in favour of retaining the tax cuts – even more so than Coalition supporters. Perhaps these responses confirm the proposition that conservative governments are adept at convincing the less well-off and the less-educated to vote against their class interests.

The Australia Institute survey finds that there is much more support for spending on government services “like health and education” than for tax cuts or spending on defence.

The main revelation from the surveys, on which Crowe and the Australia Institute report, is that for questions without a forced response there is a large “don’t know” response. Australians need to be much better informed about public revenue before they can be expected to make wise choices at the ballot box.

In the present situation, where real wages have stalled or fallen back for workers in low-paid and underpaid-jobs, and where the well-off have used their gains to drive up asset prices, contributing to a boom-bust situation, the tax cuts make no sense. In the longer term, because people’s fortunes can change quickly, there may be a case for flattening the steps in our tax scales, but why should that be at a time when we have such high public debt? Bracket creep may justify shifting the top threshold from $180 000 to $200 000, but why now? And surely there is a case for a much broader review of all our taxes, particularly in view of our overall low taxes in Australia.

The Liberal Party is prattling on about broken promises, the politics of envy and class war, but it’s unconvincing. In reality they are arguing for personal income tax cuts for people in the top ten percent of incomes, at a time when most people of more modest means are having a tough time.

1. Calculations on the number of beneficiaries are based on ATO Taxation statistics relating to individual taxpayers. The data is all available, but it requires an amount of analysis to bring it into a meaningful form. ↩

The pandemic that won’t go away

Covid-19 – sorry, it’s still around and we still need to be cautious

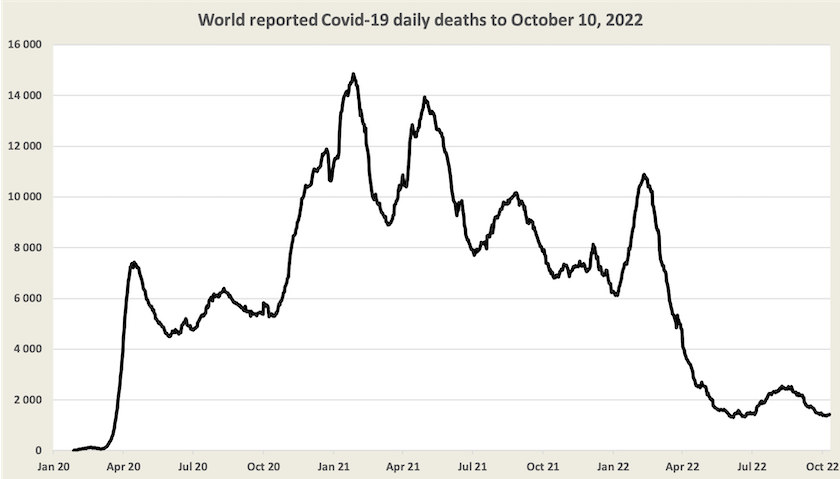

The announcement that isolation mandates were to be repealed (taking effect yesterday, Friday 14) may have given the impression that Covid-19 is on the way out, but it’s still a serious disease worldwide. While it is far less of a menace than it was in 2020 and 2021, it is still killing 1400 people a day, and it appears that deaths from Covid-19 are once again rising.

Rising case numbers in the US and Europe suggest that another surge could be on its way – maybe because of new sub-variants of Omicron, maybe because of waning immunity, and maybe because of behavioural changes associated with the onset of colder weather in the northern hemisphere.

South Australia’s Chief Public Health Officer, Nicola Spurrier, expects a peak of cases in Australia in the next couple of months. Most people will be well protected against severe illness by prior infection and earlier vaccination, but many will become ill. She recommends that people take up third-dose vaccination and fourth-dose if they are eligible.

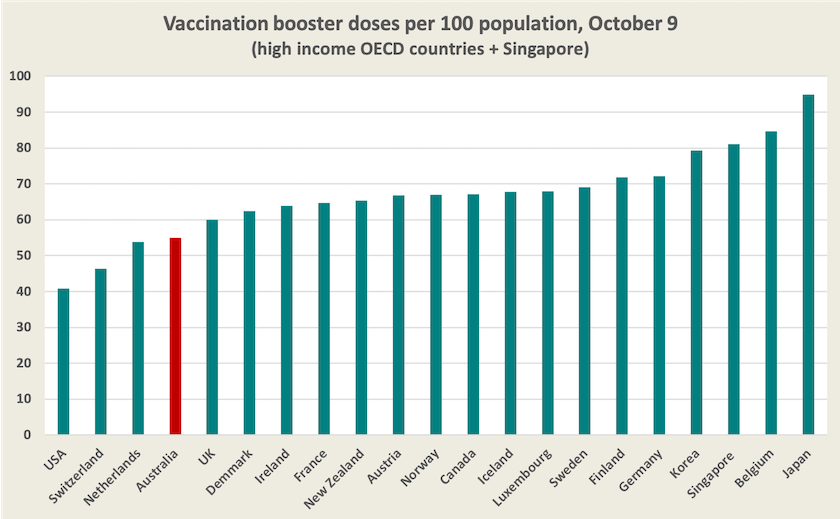

Of particular concern in Australia is our low uptake of third and fourth doses. Only about 40 percent of those eligible for a fourth dose (mainly those aged 30 or more) have had a fourth dose. While we did very well on first and second doses, our uptake of third-dose vaccination has been low in comparison with other “developed” countries. (There is only scant data on fourth-dose vaccination.)

The ABC website has an article by Sian Johnson and Yara Murray-Atfield about the relationship between vaccination mandates and people’s motivations to adapt their behaviour. They refer to work by public health expert Julie Leask, who suggests that mandates may have the unintended consequence of people becoming incautious once mandates are lifted.

A more mundane reason why cases could now rise is that some people, even if they believe they have Covid-19, will turn up at work or social events, now that mandates are lifted: many people find it difficult to understand that what is allowed in law is not necessarily ethical. Also, apart for a few particular occupations, there is no longer any government assistance for those who isolate because of Covid-19.

According to the most recent Commonwealth report cases haven’t risen as yet, but they seem to be flattening, as do hospitalizations. Deaths continue to fall – 15 per day at the end of September, and according to provisional figures, they could now be as low as 3 per day. There is evidence that in the year to June 2022 there were some thousands more deaths than normal, and which were above those recorded as Covid-19 deaths. This has led the lunatic right to claim that vaccines may have caused these deaths, but drawing on the authority of epidemiologists and actuaries, the RMIT-ABC factchecker has put down these claims.

While we have promising data on deaths and hospitalizations (so far), there is still the problem of long Covid, with its debilitating effects. The ABC reports on the work of Steven Faux, who heads a long-Covid clinic at a Sydney hospital, and others who believe that the Commonwealth chief medical officer has downplayed the risk and consequences of long Covid. They refer to research suggesting that people with triple vaccination, when infected with Omicron, had a long-Covid rate of 5 per cent.

For those seeking advice on how to adapt to a world with fewer mandates, epidemiologists Catherine Bennett and Hassan Valley of Deakin University have a Conversation article: How should we manage COVID without rules? Keep testing and stay home when positive.

Where did Covid-19 arise?

There are three opinions, none of which can be firmly verified, on the origins of Covid-19. The dominant opinion is that it made an animal-to-human transmission in a wet market in Wuhan. Asian public health experts have been warning about the risks of traditional wet markets for many years. Another opinion is that it accidentally escaped from the Wuhan Institute of Virology. The third, espoused by cold-war warrior cranks, is that the Chinese government deliberately set it loose on the world.

Raina MacIntyre, whom we have often seen on TV over the last couple of years, is understandably annoyed about the politicization of Covid’s origin and about the general way in which throughout the path of the pandemic, scientific evidence has been pushed aside by politicians, marginalizing this important issue. She does not dismiss the possibility that the virus escaped from a laboratory, but instead of implying that such an accident reflects on some distinctly Chinese sloppiness, as some politicians have suggested, she believes that throughout the world biological laboratories are not as safe as we are led to believe. Her book Dark winter: an insider’s guide to pandemics and biosecurity, will be released next month.

The Doherty Institute draws attention to a report – Independent Task Force on COVID-19 and Other Pandemics: Origins, Prevention, and Response – lending weight to the probability that Covid-19 results from an animal-to-human transfer.

In terms of public policy the specific origin of Covid-19 is less important than the broader issues of zoonotic transfer and the safety of laboratories. Even if one source is ruled out in the case of Covid-19, the other remains a hazard.

Gittins on the bright side of pandemics

The Black Death of the 14th century had its benefits, Ross Gittins writes on his website: Creative destruction: even pandemics have their upside. He describes the social and institutional changes consequent on the Black Death – changes that generally benefited the human condition.

Covid-19 has been on a much smaller scale than the Black Death, but its disruptions to the economic order have had some benefits. Two that Gittins identifies are a reduction in the number of same-day business trips people are making between capital cities, and an expansion of online business, protecting us from the horrors of shopping malls.

Other health policy – why surgeons drive Lamborghinis while GPs drive Hyundais

One revelation in the ATO’s recently-released taxation statistics is that medical specialists occupy the three highest-income occupation groups: surgeons ($406 000), anaesthetists ($389 000), and internal medicine specialists ($311 000). A little digging into the data reveals that non-specialist medical practitioners have more modest incomes. Their median income is $139 000 –$159 000 for men, $123 000 for women.

Health economist Anthony Scott has undertaken a financial analysis of medical practitioners’ practices. Their general mode of operation is to establish a corporate structure, either as a sole-trader or more commonly a jointly-owned small business.

His summary article in The Conversation is: Some GPs just keep their heads above water. Other doctors’ businesses are more profitable than law firms. His full report – Trends in the structure and financial health of private medical practices – is more readable than the summary, because it presents most data in clear graphical and tabular forms.

GPs are certainly more poorly remunerated than specialists, but even for them it is not a story of unmitigated financial hardship. They still do reasonably well in comparison with other professions, but the margins between revenue and costs have been squeezed in recent years. Those in group practices, where some costs can be shared, do better than those operating solo. This has particular implications for the viability of practices in non-metropolitan regions.

To an extent what is happening to GPs is what has happened in every profession: the income premium from a professional degree is relatively lower than it was one or two generations ago. But there are also significant problems resulting from distortions in the medical labour market, one being the incentive for graduates to bypass general practice and go on to more lucrative specializations. This, in turn, results from government policies that have subsidized private health insurance while squeezing budgets for public hospitals and for GP Medicare payments. The cost of such distortions falls to the users of health care in terms of out-of-pocket costs, which fall haphazardly with little regard to people’s means.

Also Scott’s analysis is a financial analysis. As such it does not cover long hours, stress or burnout.

UK economic policy as Stanley Kubrick would see it

Spare a thought for Britain’s newly-minted prime minister Liz Truss and her treasurer Kwasi Kwarteng (“Chancellor of the Exchequer” in that country’s quaint language), because maybe there has been some thought behind their madness.

Truss is on to something when she says she wants to restore growth in Britain’s economy, and is willing to take on the “anti-growth coalition” in order to achieve it, even if she has identified almost everyone who isn’t a paid-up member of the Tory Party as a member of that supposed coalition.

It’s easy to see the idiocy of the way she’s going about it, pursuing a Hayekian neoliberal program so savage that if it were to come off it would make Margaret Thatcher look like a social democrat. The left in Britain is beside itself in criticizing her agenda, but such criticism is about as pointless as criticizing the Taliban’s education policy or Putin’s defence policy.

To understand the broader context of her strategy, we might imagine that she and her treasurer are putting forward an economically sensible pro-growth policy – investing in skills, physical infrastructure and an energy transformation, re-structuring taxes to reward those who make a real contribution to the nation’s wellbeing rather than those who live off inherited fortunes, restructuring the country’s rustbelts, working to eliminate pockets of deep poverty, and bringing the country back to the European Community.

Such a set of policies would probably get an A+ from the country’s best economists, but it would result in the same reaction from the financial markets as the crazed policy she has put forward. No matter who is running the show, and what suite of policies they are pursuing, from Marxism through to economic libertarianism, the financial markets will disapprove and punish the government if those policies involve large budgetary cash deficits or a temporary rise in inflation. It doesn’t matter whether that deficit is financing productive infrastructure or if it is going to enrich the government’s cronies – the financiers don’t care. Their only concern is that they don’t want governments soaking up funds that should properly be circulating in private financial markets and enriching the financiers.

That’s my rough summary of an article by William Davies, Madman Economics, in the London Review of Books. It’s in a UK context, but it may help to explain why social-democratic governments, when they do achieve electoral success, are timid about pursuing policies of reconstruction, because they know what the financiers can do to them.

Davies speculates on the logic behind Truss’s and Kwarteng’s strategy. Perhaps they believe that the whole system is so rotten – so decadent and feminine to use their terms – that they want to bring on a crisis that will blow the whole joint up, allowing a new and more perfect economic life form to evolve.

We might believe that Dr Strangelove, the maniac who wanted to cleanse the world with a nuclear holocaust, was a creation of Stanley Kubrick imagination, but perhaps Strangelove is incarnate in the UK Tory Party. Life imitates art.