Politics

Sydney’s festival of really dangerous ideas

On September 10 and 11 Sydney hosted the Festival of Dangerous Ideas, which would have been better described as a forum for experts to present analysis of emerging political and economic trends – a valuable contribution to public ideas but hardly “dangerous”.

The really dangerous ideas came three weeks later, at the Conservative Political Action Conference, also held in Sydney.

“Trump administration officials and British Brexiteer Nigel Farage were invited to join a bevy of local trickle-down low-tax fantasists, opponents of anti-corruption bodies, monarchists, anti-Voice campaigners and fossil-fuel profiteers”. That’s Crispin Hull’s description of the gathering in a posting he has given the title Lessons for Australia.

The Guardian’s Josh Butler, in his article Conservative Liberals embrace at CPAC to celebrate the electoral defeat of ‘lefties’ within the party, provides a who’s who of the conference. Jacinta Price, Matt Canavan, Alex Antic, Keith Pitt, Tony Abbott, and Warren Mundine, all had a turn at the pulpit. Eric Abetz and Katherine Deeves (remember her? – the Liberal candidate for Warringah who was in mortal fear of the LBGTI community) were among the guests, as were a handful of Murdoch journalists.

A general theme was criticism of the Coalition for losing the May election – not because it had spent nine years in office ignoring structural adjustment, not because successive audit reports found it to be corrupt in administering discretionary grants, not because it wasted billions on defence purchasing, not because it had overseen deterioration in our public services, not because it had fuelled a speculative boom in housing – but for not being conservative enough. Nick Minchin was loudly booed when he refused to go along with that line. Nigel Farage described Morrison as a “letdown”. Most extraordinarily the Liberal Party’s vice president, Teena McQueen, welcomed the defeat of lefties in the election.

To whom was she referring? Josh Frydenberg (Jewish, descended from Holocaust victims); Dave Sharma (Indian heritage); Trent Zimmerman (openly gay). As Hull says, “all this would be funny if it weren’t so dangerous”.

Writing in Inside Story – Liberalism eclipsed – Mike Steketee describes the Liberal Party’s internal ideological conflicts. Nothing new about that: party members have always talked about the party being a “broad church”. The conflict Steketee writes about, however, is not the traditional left-right division on economic issues, but the strategy pursued by Morrison to pursue support in outer suburbs and non-metropolitan regions, while abandoning inner-urban electorates.

Anyone with even the slightest knowledge of what happened in Germany between 1919 and 1933 has reason to be concerned about the undercurrents at the CPAC conference. These are much more serious than any move to the right on economic issues (in fact the Liberal Party has long abandoned free markets, in favour of crony capitalism) or Morrison’s attempts to gain support from the less-educated.

Michelle Grattan, writing in The Conversation, is among political commentators who believe that the Liberals have little chance of regaining government if they stay on their drift to the far right: View from the Hill: without those “lefties” the Liberals can’t regain government. She’s probably right in the short-term, but what if the Liberals are sitting back waiting for a period of economic and social distress – a Trumpian opportunity?

Simon Birmingham, one of the more reasonable people in the Liberal Party, has called on Teena McQueen to resign. Some other Liberal Members of Parliament have signalled their annoyance. The extreme views expressed at the Conservative Political Action Conference incident reveal a serious structural problem for the Liberal Party: as it shrinks in organizational membership and in parliamentary representation, more reasonable voices are becoming marginalized, while the zealots still have their voice. The hard reality for the party is that it may have to disband and re-group, as Menzies did in 1944.

Crispin Hull is confident that our democracy is on firmer ground than America’s and Britain’s: we have the benefit of compulsory and preferential voting, an independent electoral commission, and a strongly independent High Court. Leslie Cannold writes in Crikey about threats to Australian democracy. Her article is paywalled, but the title – Be alert and a little alarmed: the price of our democracy is keeping an eye on elsewhere – provides a short summary, “elsewhere” being mainly the US and the UK.

Right-wing think tanks – the nurseries for dangerous ideas

Mike Seccombe has a major article on right-wing think tanks in The Saturday Paper. It’s mainly about the Institute for Public Affairs, which traces its origins back to 1943, but he describes the think-tank landscape more generally, including the H.R. Nicholls Society, and the Centre for Independent Studies on the right, and less ideologically-inclined organizations such as the Australia Institute and the Grattan Institute.

The right-wing think tanks were most influential last century, when their “small government”, privatization and deregulationist agenda resonated with the ideological prejudices of Coalition politicians. They have lost their influence, in part because the terrible economic consequences of neoliberal policies have been revealed, and in part because the Coalition itself backed off neoliberalism in favour of conservative crony capitalism.

The picture Seccombe paints is a dismal one of outfits still pushing an agenda of lower taxes (rather than tax reform) and keeping themselves armed to fight battles over identity and culture in a war that doesn’t exist. Climate denialism keeps them energized, while the corporate sector, once the major donor to these think-tanks, now ignores them as it goes about the serious business of investing to deal with climate change.

The Coalition’s war on capitalism

One of the most important institutions in a successful capitalist economy is a strong union movement. Unions support market capitalism in two ways. One way is by ensuring that the benefits of economic activity can be fairly distributed to those who contribute. In so doing they help capitalism maintain its social licence.

The other way is by sustaining the circularity of a market economy: workers’ wages sustain markets, the lifeblood of capitalism. Henry Ford understood this in 1914 when he doubled workers’ wages: otherwise who was going to buy cars and the other products of capitalism?

John Howard, and other senior members of the Liberal Party, have never understood this basic economics. In her National Press Club Address ACTU Secretary Sally McManus reminded us that in office the Coalition was determined to destroy unions: Employment Minister Eric Abetz openly claimed that the government was engaged in a war with the unions. Legislation was specifically designed to reduce real wages, to ensure that workers did not share in productivity gains, and to reduce employment security.

The Coalition’s success in achieving these aims is seen in the Australian economy today – runaway corporate profits, stagnant or falling real wages, further widening of wealth inequalities, and severe labour shortages. So successful have they been that many employers’ groups look on unions as institutions dominated by thugs determined to smash capitalism, rather than as partners in the economy. McManus describes the situation in the early days of the pandemic, when the Morrison government was forced to appreciate the dependence of the economy on hitherto disregarded essential workers, when most ministers “were meeting the leaders of unions who represented the working people of their portfolios for the very first time”.

Most of McManus’s address is about the need to reinstate mechanisms to ensure that a fair share of productivity gains passes through to workers. The Fair Work Commission needs to regain powers to mediate in disputes, and mechanisms to allow for collective bargaining have to be re-established.

To provide a little economic theory to her call for collective bargaining, there are arguments for firm-by-firm bargaining and for collective bargaining.

The case for firm-by-firm bargaining rests on the assumption that if some firms pay inadequate wages, workers will move to firms that do pay adequate wages, and the underpayers will have to lift their wages, or, if they cannot afford to do so, go out of business, releasing labour for employment in more productive firms.

Collective bargaining rests on the same logic, but the initial pressure is on firms to lift their wages, rather than on workers to go and get another job.

That’s the abstract theory showing how two different arrangements lead to the same outcome, but like so much basic economics it ignores the real world where there is friction in labour markets (bargaining costs and transaction costs in econospeak). As McManus explains, in industries dominated by small establishments (food service, child-minding, aged care as examples), a whole industry can be underpaying wages, and in a competitive market there is no benefit for firms to be the early movers. And even if some firms pay more reasonable wages, it is unreasonable to expect workers to bear the costs of changing jobs.

A transcript of McManus’s address is on the ACTU website. In her Q&A session starting at 33 minutes (see the link earlier in this piece) she goes into more detail about collective bargaining, long-term reforms, and issues of pandemic leave. Notably no one from the Murdoch media turned up to the session.

The Big Teal

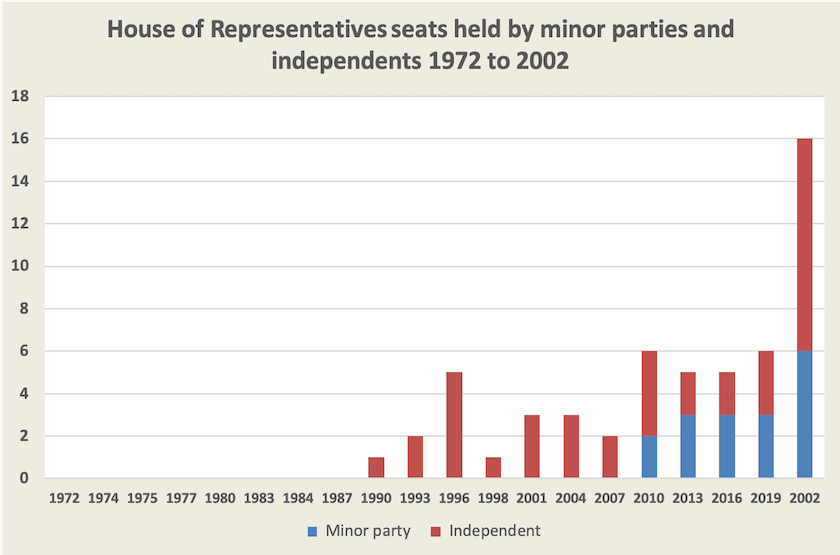

For the first 50 years after Federation, Australia’s House of Representatives was truly multi-party, but from 1951 to 1987 it was (almost) entirely dominated by Labor and the Coalition.[1]

That pattern has broken over the last 30 years, most significantly in this year’s election with the election of ten independents, including the “Teals”, shown in the graph below.[2]

On the ABC’s Breakfast program The triumph of the Teals and a new kind of politics Simon Holmes à Court, whose Climate 200 supported 9 of the Teals, provides some background to the movement, describing how it grew ten years ago from Cathy McGowan’s Voices for Indi movement.

He has written a book The big Teal correcting misinformation about independents and explaining what motivated them to seek election. They have not been a disruptive and chaotic presence in Parliament, as some claim. Rather, they have strengthened parliamentary democracy, particularly around issues to do with corruption.

In his interview he criticizes the Liberal Party for being so attuned to the Murdoch media and to people like Nigel Farage (a foreigner who, with a little help from Putin, led his country to impoverished isolation) who are urging the party to swing further to the illiberal and authoritarian right. He believes that the Liberals could win seats lost to the Teals if they could have policies more representative of the electorates they have been losing. (8 minutes)

It is notable that almost all the candidates supported by Climate 200 were women, and that women, up to about 20 years ago, had a pro-Coalition bias in their political support, but that bias has reversed. In Australia, as in other democracies, women have been turning against traditional conservative parties. Plan International, an organization campaigning for girls and young women, has published a global survey, revealing that girls and young women feel excluded from politics, and that this exclusion is particularly marked in Australia.

Holmes à Court’s Climate 200 will be supporting 4 candidates in the November Victorian election, where there are some barriers erected by the main parties but he believes Climate 200 can get around them. (Antony Green has information about the Victorian election on his blog.).

1. The exception was one term served as an independent by Sam Benson, member for Batman, elected in 1966, having been expelled from the Labor Party for his support of Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War. ↩

2. Data from Parliamentary Library Infosheet 22 - Political parties. ↩