Public policy

The Reserve Bank joins alternative lifestylers

Those who advocate more frugal lifestyles for the sake of the planet’s resources have declared October to be Buy Nothing New Month. With its 6th successive monthly rise in the cash rate target, the Reserve Bank seems to have joined their ranks.

The RBA’s statement justifying the latest increase concludes by asserting that “the Board remains resolute in its determination to return inflation to target and will do what is necessary to achieve that”. There’s no qualification about the consequences of this determination.

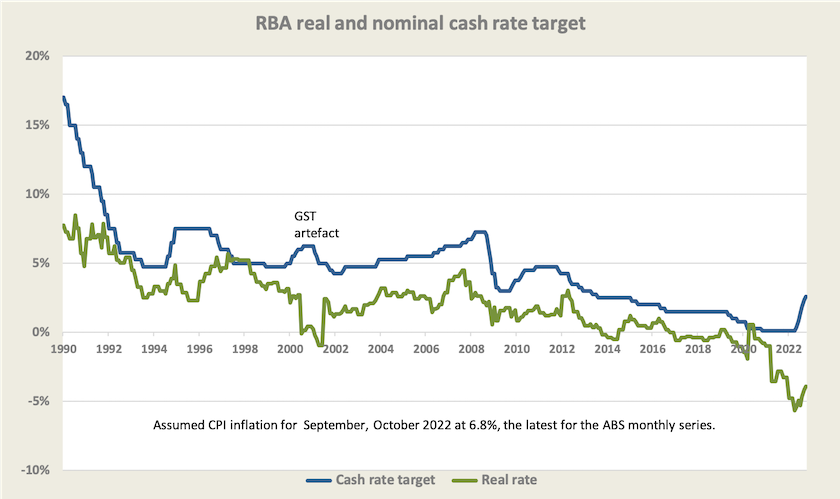

The RBA expects inflation to reduce in coming years: it estimates that the CPI will be around 8 percent this year, 4 percent next year, and 3 percent in 2024. That pattern is consistent with an economy adjusting to a severe once-off supply shock as we have had with Covid-19, rather than self-sustaining inflation. Yet the RBA is behaving as if we have an incipient situation of runaway inflation, and has forecast further interest rate rises. It is using a long-term instrument to tackle a short-term and passing problem. Admittedly it has to restore the real interest rate to positive territory, but that can take time.

Monetary policy instruments are powerful, and they are slow to take effect. Some commentators are relieved to see that the RBA has gone for a 0.25 percent rise rather than a 0.50 percent rise, but surely it could have paused to observe what effects its rises so far have had.

The media presents the usual calculations on the effects of higher interest rates on borrowers. The ABC’s Emily Sakzewski describes the consequences the last time the cash rate was raised quickly, in 1994. Her main point is that the rise in 1994 was from a high base: because borrowers were already making high repayments. This time it has been from a low base, which means the shock is greater. Also households are more heavily indebted now than they were in 1994.

There is concern about the effect of higher interest rates on home owners, particularly those who bought at the housing market’s peak. The other group easily overlooked are renters. On the ABC’s Breakfast program Patricia Karvelas gathered Eliza Owen of CoreLogic, Leo Patterson of the Tenants’ Union, and Leanne Pilkington of the Real Estate Institute to discuss the implications of rate rises for renters. There will be some effect as heavily-indebted “investors” (i.e. speculators subsidized by tax breaks) raise rents to cover higher interest payments. But the main stress on renters is a lack of supply of housing, particularly apartments, resulting in higher rental charges. Higher interest rates will contribute to this supply shortage because some “investors” will be selling properties, thus reducing the number of rental properties on the market. This could reduce the price of new housing while increasing rents. (16 minutes)

Will they be available for rent?

The policy conclusion to be drawn from that analysis is that speculators should be driven out of the housing market, to be replaced by long-term investors. Speculators make poor landlords. We need once again to regard housing as an essential service, not a financial commodity.

“Australia has a housing affordability problem”

That’s the opening sentence in the Productivity Commission Report In need of repair: The National Housing and Homelessness Agreement. Hardly news.

Its reference, from the previous government, was to review the National Housing and Homelessness Agreement. That agreement aims to improve access to “affordable, safe and sustainable housing across the housing spectrum, including to prevent and address homelessness, and to support social and economic participation” to quote from the terms of reference.

It finds that agreement to be ineffective in meeting its objective.

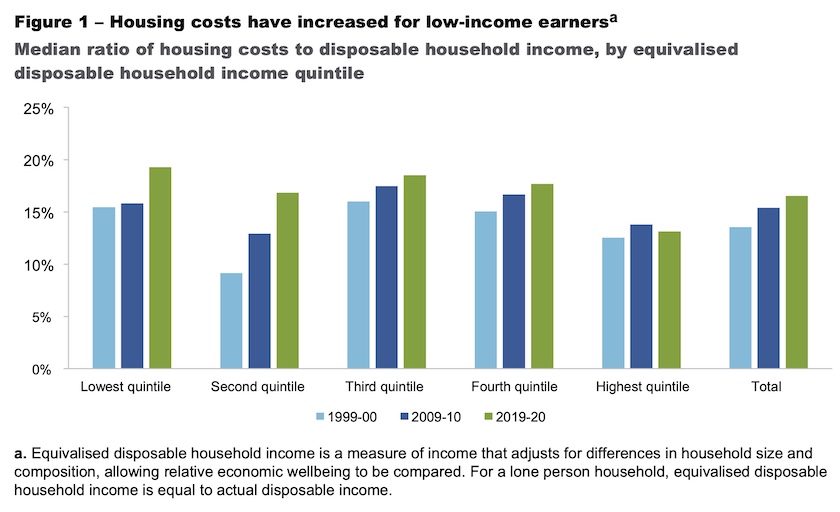

The report’s findings on housing affordability are summarized in a graph, showing rising housing costs as a proportion of disposable income by income quintile, copied below:

Note the particularly steep rise in housing costs for those in the bottom two income quintiles.

The Commission is generally not enthusiastic about demand-side programs, asserting, in particular, that “the economic case for supporting home ownership is not strong”. Its main concern is for renters, noting, for example, that 77 percent of low-income households have less than $500 a week after paying rent. It is also concerned for those who cannot get into housing at all, finding that “the public and private benefits from assisting people who are – or at risk of – experiencing homelessness are likely to be greater than helping people buy a home”.

It recommends that Commonwealth rent assistance, by far the largest government housing program, be better targeted at those who are in most stress. The long-term solution lies on the supply side, and the Commission makes little distinction between social housing and other housing, just as long as more housing at the lower end of the market can be provided.

Notably it makes no mention of the tax breaks – capital gains tax breaks and “negative gearing” allowances – that have contributed to housing becoming a financial commodity for speculators, but it is critical of state governments for some of their zoning restrictions. These criticisms do not distinguish between restrictions resulting from NIMBY pressure and those based on constraints in infrastructure that cannot cope with a higher population density. Housing has to be considered within the broader context of land-use planning, and should not be considered separately from a broader settlement policy.

Affordable financial advice

Should a financial adviser be required to act “in the client’s best interests” or would offering “good advice” be sufficient, resulting in lower costs so that more people would seek advice?

That’s the question Geraldine Doogue discusses with David Bell of Connexus Institute on last week’s Saturday Extra: Watering down financial services regulation? (14 minutes)

The context is a report on the quality of financial advice, commissioned by Treasury, its Quality of Advice Review, which includes a recently-released Proposals Paper. (There was an Issues Paper published in March this year.)

The main proposal in the paper is that rather than regulating the conduct of advisers, and requiring them to offer that advice “in the client’s best interests”, as the present regulations do, the focus should be on regulating the content of the advice. This would involve lower compliance costs on advisers, allowing more people to access advice at lower cost but without the tailored service that is directed to the specific client’s best interests.

Consumer groups are generally opposed to the idea, because it would pave the way for banks and other financial institutions to re-enter the advice industry, offering “advice” related to their particular products.

Bell observes that people tend not to think much about financial planning until retirement looms, at about age 60. He also observes that in Australia, as in many other countries, people’s financial literacy is low.

(Having been a lecturer in finance I too am struck by the general low level of financial literacy among otherwise well-educated people. Most people are unfamiliar with basic issues such as compounding, the difference between real and nominal returns, dividend and capital gain returns, and dividend imputation, even though mastering these concepts requires only early high school math. When properly presented they are easy for students to learn.)

Essential poll: we should still do more on climate change

This fortnight’s Essential poll looks at our attitudes to climate change, the Optus debacle, and our “perception for the future of humanity”.

On climate change the question is whether “Australia is doing enough, not enough, or too much to address climate change”. Three years ago “not doing enough” dominated (60 percent or higher). Now 43 percent of respondents still think we’re not doing enough. There are disappointing but predictable partisan and age differences, and a less-predictable significant gender difference, women being much more inclined than men to say we’re not doing enough.

Regarding the Optus breach, only 21 percent of people who have been surveyed say they have been affected: this is much lower than the 10 million whose data has been compromised. Respondents are very concerned about the risk of scammers stealing our personal information and are generally in support of stronger restrictions on how much personal information corporations and governments can collect. Essential also asks about how we feel about facial recognition technology as a predictor of our behaviour, and artificial intelligence making decisions for us. Theirs is some opposition, about 30 percent, to these ideas.

On the future of humanity, we’re not particularly optimistic. Men and young people are more optimistic than women and old people.

Climate change and public authorities

When we think of risks associated with climate change we tend to be concerned with private and corporate losses through fires, floods, sea-level rises and droughts, many of which are at least partially covered by insurance firms. The incidence of such risks is very much influenced by public authorities who set zoning rules and building codes, and who decide on the location of infrastructure including water supply, drainage and roads. Also public authorities are custodians of assets subject to climate risk, such as national parks.

The Centre for Policy Development has published a paper Raising the bar: managing climate risk in public authorities as a guide to best practice in managing climate risk for managers in government.

Another enduring reason for high electricity bills

Most Australians would be surprised to learn that only a quarter to a third of their bill goes to paying for the generation of electricity – the old coal-fired power stations, or the wind and solar plants that are replacing them.

The rest goes to firms that transmit and distribute electricity (the “network” companies), and to the retailers – the companies that do nothing much other than send you a bill, after making a profit from buying wholesale and selling retail, evening out the fluctuations in spot prices. Network costs typically comprise about half the bill paid by households and small businesses.

Networks are natural monopolies: it would be wasteful (and ugly) for our streets to be cluttered with the poles, wires and transformers belonging to competing companies. Conventional economic practice is for natural monopolies to be kept in public ownership, particularly in the case of capital-intensive industries with mature technologies such as electricity distribution. But in an ideological frenzy twenty years ago, the networks were put on the market and subjected to regulation by the Australian Energy Regulator. (They weren’t all sold to the private sector: the Queensland and Tasmanian governments still own substantial parts of the networks, and the Singapore and Chinese governments own parts of the Victorian network – but that’s another story.)

The Institution for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis has released a study which, in sum, claims that because of lax regulations, the networks have gotten away with about $10 billion excess profits (“supernormal profit” in econospeak), or about $1000 per customer in the National Electricity Market. Regulated electricity network prices are higher than necessary.

The report’s author, Simon Orne, explains the findings on ABC radio: Report suggests electricity consumers overpaid $10 billion. The same 7-minute session includes a comment from Andrew Dillon of Energy Networks Australia who says that the report is “misguided”, because any profits are merely transitory – the results of firms having achieved cost-savings not anticipated by the regulator. Dillon explains that the AER sets a price based on the calculated cost of operating and maintaining the network, including a normal return on capital: it does not set profits. AER Chair Clare Savage’s comments (posted on the website) largely repeat those made by Dillon.

Bruce Mountain of the Victorian Energy Policy Centre also appears on the session. He does not fully agree with the IEEFA analysis: some of what it claims to be excess profits may be reasonable costs. But he does suggest that the AER’s calculation of what constitutes a “normal profit” may be too generous because of the methodology it uses to calculate a reasonable return on capital. Mountain does not go into the detail of that methodology but it is described on the AER’s website. The AER uses a long-established model known as “CAPM” (the capital-asset pricing model), which assumes that firms need a premium over the risk-free return on capital to compensate for risk. But few ventures could be less risky than investments in transmission lines and transformers in a market with a growing demand. Firms are being compensated for a risk that is nothing more than an artefact in the math of the CAPM model.[1]

1Where half your money goes

In view of the necessary investment in transmission to connect up the nation’s renewable resources – the Australian Energy Market Operator’s Integrated System Plan – getting the right method for calculating the cost of capital is important, because up to $12 billion on new capital expenditure is involved in that plan.

1. The CAPM model uses the volatility of returns as an indicator of risk, and assumes firms will use a debt-to-equity structure consistent with that estimated risk. But volatility is a poor proxy for risk, and network firms tend to use a highly-geared financial structure, realistically appropriate for a low-risk environment, which means that their actual cost of capital is not much higher than the long-term bond rate. ↩

Health policy – false economies and lingering Covid-19

Missing and overworked GPs

Three quarters of GPs, the frontline providers of health services, report that they have experienced feelings of burnout over the last twelve months. The profession is ageing: there are not enough graduates replacing those who are retiring: consequently there could be a shortage of 11 500 GPs by 2032. Based on a ratio of around 1.2 GPs per 1000 people, that’s equivalent to 10 million people having no access to GPs. (In reality the queues would just get longer.)

These are some of the findings of a report General Practice Health of the Nation 2022, by the “Royal” Australian College of General Practitioners.

GPs are dealing with the added workload of Covid-19, and a strong rise in the number of Australians seeking treatment for mental illness.

The shortage of GPs is largely explained by successive governments’ failure over many years to index the Medicare payments for GP consultations. In rough figures the Medicare rebate for a standard consultation ($39.10) is only about 60 percent of what GPs see as a reasonable fee. Medicine is becoming a less appealing profession, and many of those who graduate find that further studies to become specialists are more financially rewarding than general practice.

The lack of indexation of fees has been a deliberate decision by ideologically-driven governments, determined to destroy Medicare as a universal model, who have seen frozen rebates as a means of eradicating “bulk billing”. Also, in the pre-budgetary processes there are often arbitrary cuts to line items in the health budget, such is the crudity of our public financial management arrangements. Non-indexation looks acceptable because it can be presented as “not really a cut”, but over many years it accumulates as a substantial cut.

According to the College report, GPs in Australia earn around $140 000 a year – not a high figure for a 6-year degree followed by a tough apprenticeship – and below the OECD average of around $200 000. (We may not be able to rely so easily on immigrants as we have in recent times.)

Even though there would be a normal level of self-interest driving the College’s bid for higher rebates, its economic case is strong. Underpaying GPs to the extent that they are leaving the profession and having to charge high co-payments, is a false economy. Those who cannot get access to a GP, either because of the price of a consultation or difficulty in arranging a timely consultation, are likely to turn up at hospital emergency departments or to delay treatment of conditions until they become severe, incurring very high private and public costs down the line.

Rumours of the death of Covid-19 are greatly exaggerated

Norman Swan seems to be greatly exasperated at talk of Covid-19 being on the way out.

It isn’t.

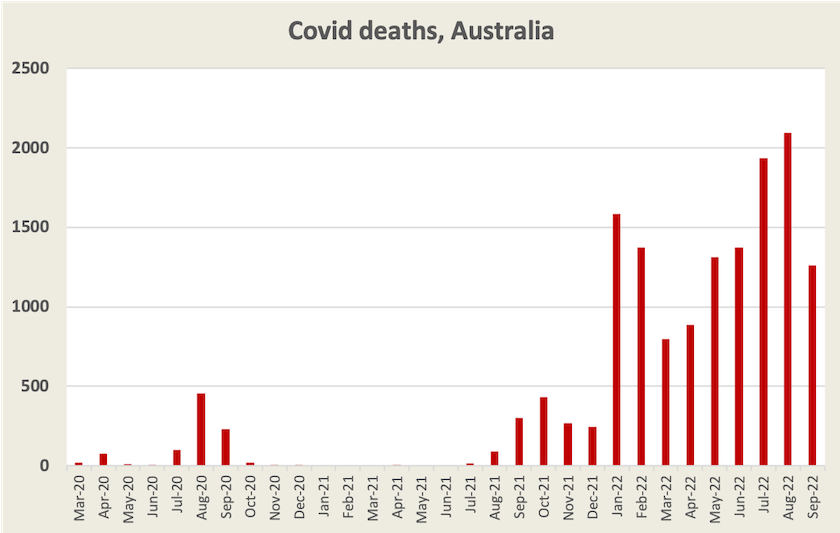

On ABC Breakfast he warns that lifting of isolation mandates does not mean that Covid-19 is on the way out. Worldwide the virus goes on mutating and surging in new outbreaks. Hospitalizations in Australia have been falling, and deaths are down from their peak, but the death rate is still high – “one Bali bombing a week”.

And we are under-vaccinated: 30 percent of people eligible for a third dose have not had one.

Swan disputes the idea that people are enjoying “hybrid immunity” because of prior infection and vaccination: the virus is still mutating and bypassing immunity, and immunity against Covid-19 wears off in time.

He is critical of the way governments seem to have pushed Covid-19 off the agenda. We need clear information and clear rules if we are to make wise choices about taking public health measures and socializing. (6 minutes)

Swan’s warning is echoed in a Conversation contribution from Raina MacIntyre, Brendan Crabb and Nancy Baxter: If you think scrapping COVID isolation periods will get us back to work and past the pandemic, think again.

If we need convincing that the virus is still with us, below is a chart of deaths, month by month, since the virus first appeared in Australia: 13 000 of Australia’s 15 000 Covid-19 deaths have occurred this year. Any economic benefit from relaxing isolation requirements will be short-lived, they warn. Prior infection provides only waning immunity. Re-infection can be worse than the initial infection, and it can heighten the risk of contracting other severe diseases. They recommend measures to mitigate the transmission of Covid-19 through “raising rates of boosters, widening access to antivirals and other treatments, masks, safe indoor air, and widely accessible testing”.

The advice from public health experts is clear, but will bully bosses put short-term performance and their desire to display their status ahead of people’s health? Will they refuse to allow people to work from home? Will they crowd people into cramped open offices? As research in organizational behaviour demonstrates, insecure middle-level managers are often more concerned about preserving the fragile symbols of their authority than in attending to the organization’s productivity or the wellbeing of their subordinates.

Latest Covid-19 data

The most recent case numbers and statistics from the Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care show that the number of Australians in hospital and in ICU with Covid-19, and the number of deaths of people with Covid-19, has continued to fall. According to the most recent confirmed figures, in late September around 20 people a day were dying from or with Covid-19, and subsequent provisional figures show a continuing downward trend. This brings Australia’s death rate broadly into line with the rates in other “developed” countries.

Does this contradict the advice from Norman Swan and others? Not really. Their warning is about the way Covid-19 appears in waves as people slacken off in their preventative behaviour, the way protection from vaccination and prior infection diminishes, and the risk of new variants. And a daily Covid-19 death rate of 20 is a large proportion of our daily death rate from all causes of 470.

The ABC – diminished by governments afraid of independent media

One thing you don’t see on Liberal Party campaign material is the motion, passed by a two-to-one majority at their peak council in 2018, to privatize the ABC.

This is just one of the revelations in Martyn Goddard’s piece on his Policy Post: After 50 years of cuts, is it now too late to rescue the ABC? he takes us through 50 years of the relationship between the ABC and the Commonwealth Government. Hostility to the ABC has come mainly from the Coalition, but also from Labor at times. The Coalition has a track record of cutting funding for the ABC, while Labor has generally restored funding, but not enough to compensate for Coalition cuts. Goddard lists the net losses over the eight years of Coalition government in physical terms, including a cut of 640 staff members and a 26 percent reduction in commissioned drama.

To return to Goddard’s question, he concludes that although in our current era we have more need of independent journalism than at any time in the past, “the ABC’s role as a comprehensive broadcaster is likely to be permanently reduced. That’s an inescapable reality of costs and funding”.

Education at a glance: promising developments

The OECD has published its regular update of Education at a Glance for 2022 – a 460 page document of comparative education data across OECD countries.

The most promising finding is in its summary of tertiary education attainment:

The average share of 25-34 year-olds with a tertiary qualification increased from 27% in 2000 to 48% in 2021 across OECD countries. On average, tertiary education is now the most common attainment level among 25-34 year-olds and will soon be the most common among all working-age adults across the OECD. The increase in tertiary attainment was especially strong among women. Women now make up a clear majority of young adults with a bachelor’s, master’s or doctoral degree, at 57% of 25-34 year-olds compared to 43% for their male peers.

This document presents the data without going into the political and economic implications of such findings. What does higher education attainment mean for the populists who seek and sometimes achieve office on the franchise of the unschooled? What will be the consequences politically and economically of women being more educated than men?

The report’s tables indicate that Australia has achieved sound education progress compared with other OECD countries. Among 25-34 year-olds, 54 percent of Australians now have tertiary qualifications, up from 45 percent ten years ago. That puts us among the higher achievers, but Japan and Korea are still well ahead of us. As with other countries Australian women are outpacing men in education attainment: 62 percent of women have a tertiary education compared with 46 percent of men.

The media have given a fair bit of attention to the revelation that Australia is heavily reliant on private funding for education and that we were one of only a few countries to reduce public expenditure on education between 2019 and 2020. A glance at Chapter C – “Financial resources invested in education” – confirms these reports. The only OECD countries less reliant on public spending are Turkey, Colombia, Chile and Mexico and we were one of only two countries to outlay less public expenditure on education in 2019 and 2020. (Hungary was the other.)

The report also confirms that Australia is among a handful of countries with high student fees (in the order of $US5 000 to $US10 000) for university study. Elsewhere in the document (Page 80) it is revealed that in comparison with other countries Australian graduates enjoy very little premium in earnings compared with graduates in other OECD countries. An Australian with a bachelor’s degree enjoys an earnings premium of 37 percent over non-graduates, while a Chilean graduate enjoys a 179 percent premium. This is unsurprising because it’s the operation of the laws of supply and demand: as countries’ education attainment advances, the earnings premium reduces. But it calls into question the distributional justice and allocative efficiency of Australia’s policies of increasing tertiary education fees over recent years and decades.

The other significant finding in relation to Australia is that in 2020 we had 458 000 foreign students in our tertiary education institutions, second only to the UK which had 551 000 foreign students (with 2.6 times our population).

Budget advice

So far questions about whether or not the government should go ahead with promised tax cuts seem to be the main issues in discussions about the Commonwealth budget, to be presented on Tuesday October 25. Will Labor break a promise or will it be guided by good economic and fiscal advice, and by observing the unfortunate misadventure of Britain’s Liz Truss? The Financial Review’s Phil Coorey believes that the government is gently building a case for ditching the cuts. David Speers reports from economists who suggest that the government should keep the cuts, but in a more progressive form.

There is disagreement in the party, but presumably they will resolve their differences, with each side understanding the other side’s perspectives and principles.

Shadow Finance Minister Jane Hume said on an ABC Breakfast interview that the tax cuts are good economic sense (have they still learned nothing about economics?) and that a government should not break election promises (have they forgotten about Tony Abbott?). Her defence of tax cuts is close to economic drivel. There is no point in giving any more money to the well-off: fiscal and monetary stimuli of the last few years have gone mainly to the financially secure, who, rather than investing their gains productively, have simply driven up the prices of equities and real estate. (9 minutes)

Building on its work concerned with redefining progress, the Centre for Policy Development has spelled out principles for an effective wellbeing budget. Clear goals should be established, and there should be an analytical process to assess progress towards those goals. Governments should “commit resources for research and analysis of the complex causal dynamics that generate the sort of outcomes Australians want to see, learning from existing preventative work underway overseas and in Australia”. A genuine commitment to wellbeing will necessarily involve public servants re-conceiving the way they approach public policy and deal with stakeholders.