Other public policy

Is a recession on the way?

Not necessarily, writes Peter Martin in The Conversation: A global recession looks increasingly likely – but here’s how Australia could escape it. He’s reasonably certain that there will be a recession in the US, where the Fed seems to be determined to kill inflation, even if it throws the country into recession – echoes of the Vietnam war-era aphorism “we had to destroy the village in order to save it”. The UK, rarely a model of sound public policy, has embarked on the madness of tax cuts and fiscal expansion that will cost ₤161 billion and will drive the ₤ to parity with the Turkmenistan Manat. He doesn’t mention China where a zero-Covid policy is inflicting economic damage, or Italy which is yearning for a replication of the economic idiocy of the Mussolini government.

Martin’s conditional optimism is based in part on commodity prices. Although they have fallen, and may fall further because of global conditions, they are still reasonably strong, thanks to Putin and his bellicose inner circle. And he hopes that our Reserve Bank does not blindly follow the US Fed or the Bank of England.

Our inflation fears may be assuaged if we stop being so obsessed by the $US-$A exchange rate. Over the last few years, while the $A has fallen sharply in relation to the $US, it has risen in relation to the trade-weighted index – the countries with which we actually trade. Perhaps if you have had your heart set on a skiing holiday in Aspen, you may consider a holiday in Tuscany instead.

If you are wondering what drives the thinking of central bankers, John Edwards has a short article in Inside Story: Central bankers unbound, which is a review of a work The Fed Unbound by Lew Menand. Edwards explains why, in economic policy and in the political debate, central banks have risen to prominence in recent time. His article is a contribution to the long-standing debate about the choice between fiscal and monetary policy as means to stabilize the economy.

Commenting on the US Fed’s recent hikes in interest rates Robert Reich has a nine-minute scathing criticism of the Fed (and by extension other central bankers), in an appearance before Congress, for what he sees as an assault on workers’ wages. The inflationary pressure is coming from corporate profiteering, made possible by industry concentration and supply shortages.

Can Australia lift its productivity performance?

The Productivity Commission has published two more interim reports on productivity.

“Innovation for the 98%” is the cryptic title of the Commission’s third interim report. This is a reference to its finding that only 1 to 2 percent of Australian businesses innovate in ways that are new to the world. This report is about the other 98 percent. “Much productivity improvement involves the wider adoption of established, even dated, technologies and practices among those millions of businesses”. In those 98 percent productivity improvements will mainly be incremental, and will depend largely on the quality of management. The Commission refers to “the huge power of small changes across many firms”.

The Commission also stresses the opportunities for innovation in the public sector. That’s a break from the neoliberal view of the public sector as an indulgent and unproductive overhead.

To promote innovation the Commission has a gentle rebuke of industry- or firm-specific interventions by government. It writes that “the drivers for diffusion are less about specific government funding programs than about getting broad market settings right to create a vibrant business environment”.

It is notable that the Commission focuses more on human capital rather than physical capital as the path to improving productivity.

That emphasis on human capital is refreshing. The Abbott and Morrison governments pursued a war on knowledge, seemingly in the belief that education was simply some luxury for enjoyment by middle-class liberals. Yet evidence from around the world shows that years of schooling are strongly correlated with a nation’s productivity, international economic competitiveness and strength in other dimensions. A recent Foreign Affairs article by Nicholas Eberstadt and Evan Abramsky – America’s education crisis is a national security threat – points out how in terms of education, the US, and by extension similar countries, is already slipping relative to China and will be overtaken by India in a few years.

The Commission does not mention government policies that have coddled small businesses. They could examine whether national productivity has been improved by family trust concessions, or by instant depreciation allowances for twin-cab Toyota Hiluxes bought by small business owners.

The Commission’s fourth interim report has the buzz-word title “A competitive, dynamic and sustainable future”, but it is really about investment. Private investment in Australia has stagnated in recent years: that was in train well before the pandemic arrived. The Commission provides evidence that firms have become more risk-averse, and in spite of reduced borrowing costs have been applying high hurdle rates for new investment. It notes that there has been increasing industry concentration and therefore less competition and increased mark-ups in the business sector.

It devotes a chapter to the investments needed to deal with climate change, both in terms of reducing emissions and in coping with the effects of climate change. It takes a not-too-subtle swipe at successive governments for their attitude to carbon pricing:

Broad-based explicit carbon pricing mechanisms generally promote least-cost abatement across an economy. However, Australia has implemented a suite of alternative policies that impose a range of implicit carbon prices on the economy, some much higher than likely under explicit carbon pricing.

Unsurprisingly it mentions a number of regulatory impediments to competition. The Commission can generally be counted on to take a deregulationist line, rather than suggesting ways to improve resource allocation by increasing government involvement. For example in this report it is critical of regulations on private health insurance, but it does not canvass the benefits of abolishing the industry altogether and relying on a single national insurer.

If one were to summarize the findings of this report, without the style restraints applied by government agencies, one could say that it reports on a private sector that has been conditioned to easy returns through resource exploitation and successful rent-seeking from successive Coalition governments that have placed corporate profits ahead of the public interest.

Transport emissions: the tradies’ future is an electric twin-cab

The government has released a short consultation paper: National Electric Vehicle Strategy. It asks for public input on how emissions from the road transport sector can be reduced, through increasing the uptake of electric vehicles and through tighter fuel efficiency standards. It also asks for suggestions on how the revenue lost from fuel excise should be replaced as gasoline and diesel sales fall.

Real men drive big twin cabs

Curiously, throughout the paper it uses the single word “emissions” without clarification as to whether they relate only to greenhouse gas emissions, or to all tailpipe emissions.

Submissions should be made by the end of this month. There is a webpage with information on making a submission, with a reminder that there will be online sessions to discuss the paper’s options.

When transport policy is discussed in the public arena there is often a strong discussion about cars, but it should be remembered that cars account for only 45 percent of transport emissions, the balance being light commercial vehicles, trucks and buses.

Undoubtedly some will argue that Australia has a special need to retain internal combustion vehicles because of our vast distances. But we are heavily urbanised in comparison with other countries, and as the paper points out, in Sweden, another country with long road distances, 43 percent of light vehicle sales last year were EVs, compared with 2 percent in Australia.

Energy prices: relief is some way down the track

The Australian Energy Regulator has released its State of the energy market 2022. The overview summarizes the immediate situation:

Electricity and gas wholesale market prices were relatively low at the start of 2021 but have since surged to record and persistent highs, driven by a perfect storm of supply-side constraints.

It goes on to suggest that those high prices will persist for at least the next two years.

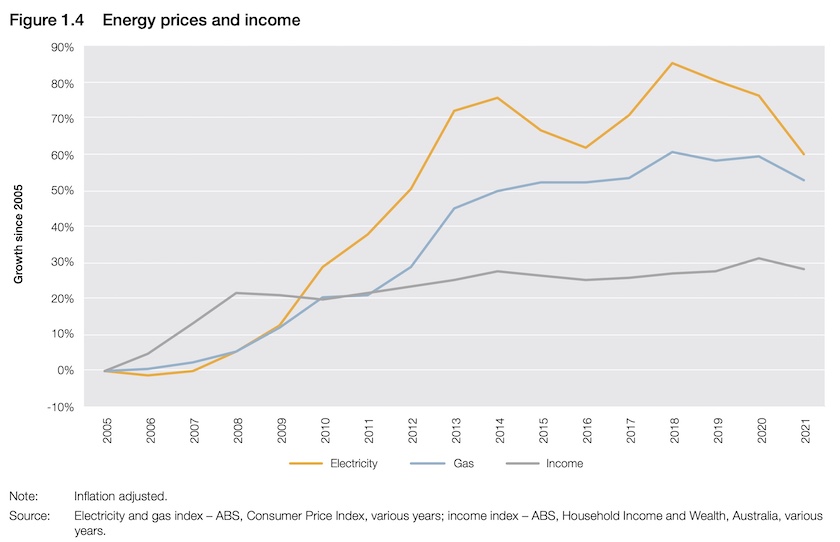

For households the story is presented in one of its key charts, copied below:

The good news is that it sees an acceleration in our transition from a centralized fossil-fuel based electricity system towards a dispersed renewable-based system. But that will require substantial new investment in electricity transmission networks. Unless the government picks up the tab for all or part of the investment, which would spread the cost across the community rather than as a de-facto sales tax on electricity consumers, electricity prices will stay high for some time until we have the infrastructure in place to take advantage of the low cost of electricity generated from renewable sources. That’s the catch-up cost of a long period of deliberate neglect.

A related publication is the Energy Security Board’s Health of the National Electricity Market report for 2022. The Board is concerned with reliability of supply, particularly during the transition from fossil fuel to renewable energy. In addition to this medium-term need, which presents many problems to be overcome, there have been short-term disruptions to the market, driving up peak prices, including unexpected failures in old coal-fired generators, the Ukraine war pushing up fossil fuel prices, and extreme weather events. These have resulted in an increasing number of situations when the network has been close to failing to provide adequate supply.

The report reveals ways in which the retail market is not working well for the least well-off customers, whose electricity usage is generally higher than better-off customers. This is mainly because they cannot afford insulation and other investments, such as batteries and photovoltaic panels, that better-off consumers use. Many customers struggling with high electricity bills are renters.

Technologies that can and should be employed to improve security and smooth out demand are not being fully utilised and are not always integrated with the electricity network. In many households smart meters have been installed, but consumers are not using them to control charges.

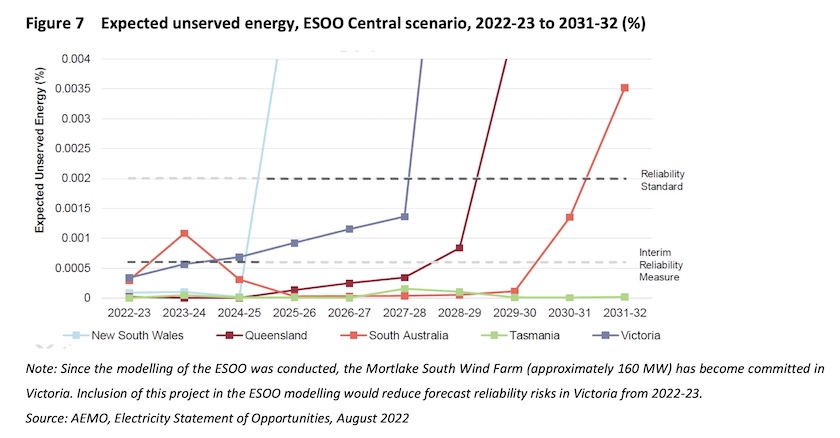

The Board has factored the retirement of coal-fired stations into its supply-demand forecasts. It foresees significant gaps between supply and demand – “unserved energy” in coming years, shown below in one of its key diagrams.

These shortages are state specific. It is therefore important that investment in transmission, as laid out in the Integrated System Plan, is expedited. Large investments are needed – $30 billion out to 2050. These are in addition to needed investments in renewable resources.

These two reports, presented in the last few days, are about medium and long-term trends. This week has been a busy time with significant announcements in the energy sector. Renew Economy has articles on Queensland’s 80 percent renewables target for 2035, incorporating massive pumped-hydro projects, and on AGL’s plan to close its last coal-fired plant by 2035, ten years earlier than previously planned.

Optus – a case study in self-regulation and privatization

On Monday night Cyber Security Minister Clare O’Neil appeared on the ABC’s 730 Report explaining the government’s response to the Optus data breach. She covered the extent of the breach and the vulnerability of customers to identity theft – which has been covered on many media.

O’Neil was mainly concerned about how such a basic breach happened – how a huge window could have been left open for thieves. She could have justifiably blamed the former government for its laxity, but she refrained from such politicization. She did, however, refer to the weakness in legal cyber protection that the Albanese government has inherited. The Coalition had introduced well-considered cyber-security legislation, but it exempted Telcos, convinced by their assurances that they could handle cyber-security without regulation. (9 minutes)

Three academics from Sydney and Macquarie Universities have informative articles on The Conversation with advice for those 10 million Optus customers whose data may have been stolen. Their first article What does the Optus data breach mean for you and how can you protect yourself? A step-by-step guide provides immediate advice, which, judging by the length of queues for replacement drivers’ licences, many people are heeding. The second article The “Optus hacker” claims they’ve deleted the data. Here’s what experts want you to know gives some insight into how the theft has worked.

The immediate policy response has to be about tightening up regulation and setting higher penalties for not protecting customers’ data, as Minister O’Neil promises. There are also broader policy issues that the government may be less inclined to address, such as the appropriateness or otherwise of allowing industries to self-regulate, and more basically the wisdom of ever having privatized telecommunications.

It is indeed extraordinary that a breach like this can occur. Government agencies handling sensitive information store a great amount of data, but they keep it on computer systems with no connection to the rest of the world, physically separated from computers connected to the Internet. Private businesses have a thing or two to learn from well-run government enterprises.

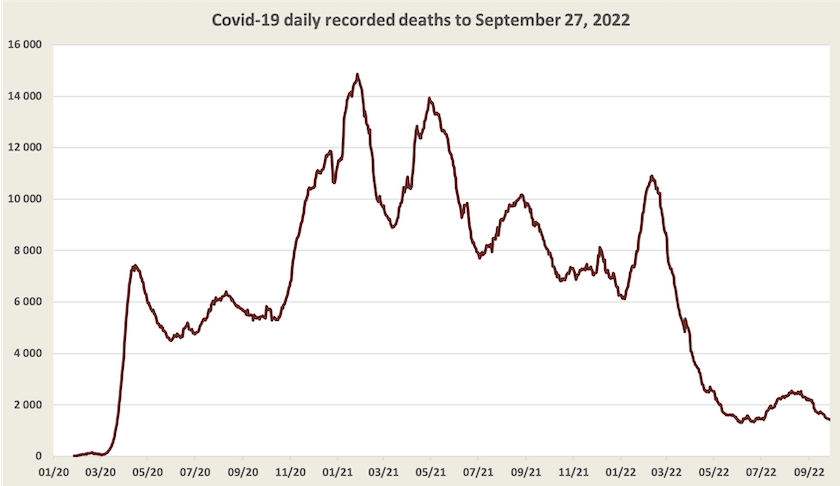

Covid-19 is still hanging around

Worldwide Covid-19 deaths are falling.[1] The big picture is the decline in deaths since the peak in early 2021 – a decline following a pattern familiar to many system analysts, because there is a certain amount of “ringing” – ongoing waves around the trend, generally of weakening intensity. There could still be more waves as the northern hemisphere goes into winter, as people slacken off from preventative health behaviour, and as the protections of vaccinations and prior infection wear off.

The Commonwealth’s weekly figures on case numbers and statistics show a continuing fall in notified cases, although the curve is flattening. Deaths are continuing to fall: provisional figures suggest that nationally daily deaths are now down to around 5, but these provisional figures seem to be the most optimistic estimate. Australia is reporting around 25 daily Covid-related deaths to the WHO, which, per capita, is a little higher than the death rate in western European countries, but it is on the way down.

The number of people in hospital with Covid-19 continues to fall – 1700 at September 27, down from 5400 in late July, the peak of the current outbreak.

The Halton Review – practical advice for policymakers

Just three months ago the Minister for Health and Aged Care commissioned an independent review of “the purchasing and procurement of COVID-19 vaccine and treatments to inform the next 12-24 months”.

The review, conducted under the direction of Jane Halton, was published by the government on September 27. Its 8 recommendations, in line with its brief, are mainly about managing procurement and distribution, and they include a recommendation that the government now take steps to ensure an adequate supply of vaccines and treatments in 2023 and 2024. On the ABC PM program Halton expressed mild surprise that the government has not made those orders as yet.

She also recommends that public health campaigns be used to improve booster coverage. On the same PM program she said that she was disappointed that only about 40 percent of people who are eligible for a fourth shot have taken up the offer: we’re running behind comparable countries. (5 minutes)

One notable recommendation is that the roles of decision-makers and advisors should be clarified, and that “reasons for decisions should be evidenced including indicating where they are based on judgment” – an implicit criticism of both the current and previous government for their secrecy and keeping much information hidden from public view.

The review did what it was asked to do: it provided advice to the present government on handling Covid-19 in the medium term. Yet news.com.au announced the review with a headline Report into vaccine procurement declines to criticise Scott Morrison, as if everything a government does is for partisan point-scoring and that this inquiry delivered an own goal. Somehow the Murdoch media cannot understand that sometimes governments commission inquiries in order to advance the public interest.

Vaccination

As the Halton Review points out, although Australia achieved high coverage of first and second-dose vaccination (93 percent and 90 percent of the eligible population), our performance on third and fourth doses has been less impressive, and vaccination rates have virtually stalled.

Because not many countries are recording fourth doses, it is not easy to compare Australia’s fourth-dose cover with other countries, but there is data on third dose cover, and at 55 percent of the population it is low.[2] Most “developed” European and Asian countries have third-dose vaccination cover between 60 and 70 percent. The US stands out with only 40 percent cover. Within Australia there is considerable variation in cover – from 47 percent in Queensland to 62 percent in the ACT.

1. There has always been a bias in these figures, provided by the WHO, because in many poor countries deaths have not been recorded. But there is no reason to doubt that they depict the general trend in the spread and attenuation of Covid-1. ↩

2. That is 55 percent of the entire population, or 72 percent of the eligible 16+ population. ↩