Other public policy

Everything you ever need to know about housing policy

It’s the land, not the house

Arguments about housing can degenerate into trench warfare as protagonists push their solutions to our housing shortage – provide more help for buyers, free up supply constraints, ease zoning rules, build public housing, abolish negative gearing breaks, stop immigration …

Brendan Coates of the Grattan Institute has used housing as a theme for the Annual Henry George Commemorative Lecture, with the title The Great Australian Nightmare.

Henry George believed that because the supply of land is fixed, unlike other factors of production (labour and capital) its owners enjoy economic rent, and that therefore land ownership is the main source of inequality. He advocated land tax as the main means of collecting public revenue.

George’s ideas went out of fashion as, in confirmation of Marx’s ideas, ownership of capital became the main source of inequality as agricultural productivity improved, and as settler societies in the New World stole more land from original owners.

But land ownership should be back on the agenda Coates suggests. His concern is urban land this time, because its owners are enjoying economic rent manifest as income and wealth accumulation (and “rent” in the everyday use of the term).

That’s the theoretical background to his presentation. It is also replete with data on housing. He corrects a few myths: young people aren’t blowing their income on smashed avocado rather than saving for a deposit; immigrants do add to housing demand and push up prices, but only by a small amount; some property developers are quite reasonably demanding that zoning laws are impeding construction of the type of housing people want because not everyone wants a free-standing house on a 0.1 hectare block.

For public policy responses, he urges a raft of reforms, rather than a focus on one issue.

A different perspective on housing is provided by three academics from RMIT University, writing in The Conversation: “We haven’t built it, and they’ve come”: the e-change pressures on Australia’s lifestyle towns. From a general public policy viewpoint the move of working-age people to country towns makes good sense, but this migration is putting infrastructure and health services under pressure. They quote Helen Haines, Member for Indi, who says “For a long time, when we talked about regional development, we said ‘build it and they will come’. Well we haven’t built it and they’ve come”.

When will houses become more affordable?

Houses have become cheaper and they have become more affordable if you depend on the bank of mum and dad, or if you made a fortune at Star Casino before you were 25. But for lesser mortals buying their first house and having to take a mortgage, the rise in interest rates affecting mortgage repayments are greater burdens than any offsetting fall in house prices that result from higher interest rates. That will be the case for some time.

That’s the main conclusion in a speech delivered by Jonathan Kearns of the Reserve Bank: Interest rates and the property market. It could be two years before houses become more affordable for first home buyers using mortgage finance.

Between the highly cashed-up who need no mortgage, and those who take the maximum mortgage, there is a whole spectrum of house buyers. If no one got a head start and everyone had to take a maximum mortgage, the effects of higher interest rates and lower prices would pretty well offset each other, but those who are more cashed-up and take less mortgage finance tend to sustain high house prices. That’s why there is a significant lag between interest rates rising and house prices falling.

Kearns’s paper has some revelations about sectors of the housing market. Prices of the most expensive houses (75th to 95th percentile) have fallen more sharply than the prices of lower-priced houses, and house prices outside capital cities have held up more strongly than prices in capital city regions.

The US is becoming a “developing country” and we’re following its path

Most people whose formative years were in the last half of the twentieth century grew up with the image of the United States as the world’s hegemon, as a strong democracy, and as a country that had achieved a basic decent living for all even though its income and wealth distribution was not particularly egalitarian. To billions of people there was worth striving for more than a US “Green Card” with its entitlement to live and work in the promised land.

Writing in The Conversation – US is becoming a “developing country” on global rankings that measure democracy, inequality – Kathleen Frydl of Johns Hopkins University updates that image with reference to two indicators that look at more than a country’s GDP. These are The Economist’s democracy index and the UN Sustainable Development Index.

On the Economist Democracy Index, the US falls into the category of “flawed democracies”. In Australia we still belong in the category of “full democracies”, but in our region both New Zealand and Taiwan rank more highly, and the Nordic countries lead the pack.

On the UN Sustainable Devlopment Index, an index that incorporates 17 sub-indices covering people’s material conditions, health, safety, housing, environmental sustainability, inequality and others, the US comes in at position 41, marked down badly for inequality and unsustainable production and consumption, and with mediocre ratings on most other indicators. Lest we feel too smug, we come in at position 38, and like the US we are marked down for inequality and unsustainable production and consumption.

On the sustainable development index the Nordic countries, Germany and Austria lead the pack. Even Ireland, the UK and Italy, countries from where immigrants have come to Australia seeking better lives, rank well ahead of us.

Frydl explains that America’s poor showing is due to “structural disparities in the United States, which are most pronounced for African Americans”.

A clever Australia needs more science teachers and more women in STEM

The Conversation has two articles on ways to build our capacities in STEM.

Lisa Harvey Smith of the University of New South Wales points out that More women are studying STEM, but there are still stubborn workplace barriers. Although it’s from a small base (less than 20 percent), there has been an impressive rise in the number and percentage of women graduating with STEM qualifications. But there are blockages in the workplace, where women experience pay gaps and inflexible employment arrangements. Harvey finds, for example, that five years after graduating only one in ten STEM-qualified women were working in a STEM industry.

Tracey-Anne Palmer of the University of Technology Sydney reports on the barriers facing science teachers in Australia. There are many long-standing vacancies for science teachers, and in most schools science is taught by non-science teachers. As with other teachers, science teachers are overburdened with non-teaching tasks – in fact more so than other teachers because of safety requirements and other provisions in science laboratories.

Stage 3 tax cuts – a promise Labor must break

John Hewson’s regular contribution in the Saturday Paper last week was a little advice to the government on fiscal policy: Albanese’s budget reality check. It’s mostly about the Reserve Bank’s determination to raise interest rates, which Hewson sees as necessary to combat inflation in our structurally weakened economy, and as part of a global movement by reserve banks. Fiscal policy should also play its part in cooling the economy. In this regard he urges the government to be ruthless on the previous government’s boondoggles and to have the political courage to drop the promised stage 3 tax cuts.

Covid-19 is waning but it’s still with us

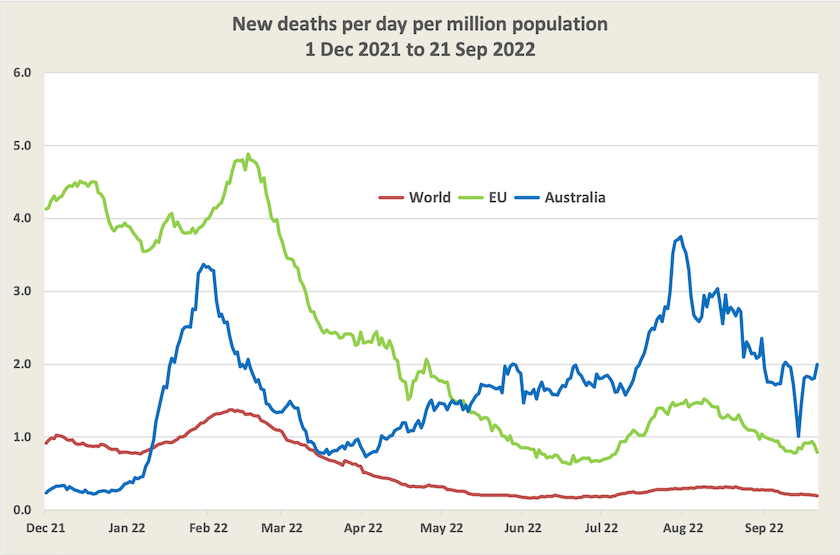

From WHO data, to which Australia contributes, it’s evident that Covid-19 is waning, but there is no evidence that it’s making a hasty exit. The graph below, drawn from WHO data, shows the trajectory of Covid-19 deaths worldwide, in the EU, and in Australia since the current Omicron variant broke out last December. Australia’s deaths, as reported to the WHO, are falling rapidly, but the apparent bounce in recent days may be no more than a result of states being lax in reporting deaths, because there is no evidence of a preceding rise in cases or hospitalizations.

World figures – the red line – presents a deceptive picture, in part because many poor countries are not reporting deaths accurately, and China, which accounts for a fifth of the world’s population, is sticking to a zero Covid policy. But like the EU curve the world curve shows a fall from the northern hemisphere winter peak.

Now that daily reporting has given way to weekly reporting, the Commonwealth has been developing a website on case numbers and statistics, showing cases, deaths, vaccinations, hospitalizations and treatments, mainly in graphical form.

The report to 20 September shows a continuing fall in case notifications, but not much weight should be put on reported cases because there is significant underreporting and the rate of underreporting is probably increasing.

Its chart on deaths suggests that our daily death rate is now around 7 a day, with a significant margin of error. That’s a steep fall from the 75 a day at the end of July, but it is consistent with earlier falls in hospitalizations. It would equate to around 0.3 per day per million population. That is plausible: it’s about the same as the rate in the UK and France.

Its data on hospitalization and on the virus’s impact on aged care homes shows promising trends.

This is all promising, but about all that can be said with certainty is that hospitalizations and deaths are falling and that the risk of suffering from a severe case of Covid-19 is much lower than it has been over most of this year so far. It would be rash to suggest that cases and deaths will go on falling, however. Slackening of social distancing and mask wearing, and waning protection from vaccines and prior infection, could see the virus’s rate of reproduction rise above one, and there is the omnipresent risk of a new variant.

Lockdowns – a retrospective

Nicholas Biddle and his colleagues at ANU have studied the effect of Covid-19 lockdowns on people’s life satisfaction. They have also studied the effect of cases of Covid-19 and deaths on life satisfaction.

Unsurprisingly lockdowns had a negative effect on life satisfaction. Also unsurprisingly the incidence of cases and deaths in one’s city or region also had a negative effect, but less severe than the effect of lockdowns. Young people were particularly hard hit by lockdowns.

The researchers acknowledge that they didn’t consider the counterfactual – the distress that would have resulted had there been no lockdowns and the virus had spread rapidly through an unvaccinated community.

The study is summarized on the ANU’s website, which has a chain of further links leading to the study. The study has a great deal of data, in easily accessed form, about lockdowns by data and region. The lockdowns were tough all over Australia in the first half of 2020, and in Melbourne for the rest of that year. Melbourne and Sydney were again subject to tough lockdowns in late 2021. It’s a useful reminder of what Australians in different regions have experienced over the last 30 months.

Footy news

News media are providing plenty of coverage of allegations of shocking behaviour by one of Australia’s football clubs. ABC indigenous affairs editor Bridget Brennan writes On a dark day for the AFL, the full impact of Australia's history weighs heavy. Her article puts the issue into the wide context of the brutal separation of young indigenous people – the stolen generation – from their families and their culture. Footballers’ separation from families is just one aspect of that brutality.

Writing in The Conversation Matthew Klugman of Victoria University puts the allegations about the Hawthorn club into the context of bad behaviour of AFL teams generally – racism, misogyny, and their tolerance of physical violence: As the 2022 AFLM season comes to a close, the game must ask itself some difficult questions – especially on racism.

The allegations have exposed once again the brutally paternalistic and controlling conditions some “coaches” (a misnomer because they are more like martinets than trainers) impose on footballers. It’s a process in which grown men are systematically infantilised, presenting a tremendous challenge when they have to adjust to normal civilized behaviour once their football days are over.

Of course these allegations should be subject to inquiries and, if proven, to the full force of racial discrimination law. But the problems are systemic, to do with the transformation over many decades of football from a game to a commercial venture in which megabucks are at stake, and which supports a parasitic sport gambling industry. The ABC program The Money devotes a whole 30-minute program to the big business of online sports betting. The techniques sports betting companies use to lure naïve punters make poker machine clubs look virtuous by comparison.

Governments could help redeem football by ceasing to invest public money in stadiums (there is no market failure justifying subsidies for spectator sports), redirecting funding to community participatory sports (guided by objective and clear criteria), and banning sports betting.