Other public policy

Economists are shocked to learn that school teachers are overworked

The Productivity Commission has released its interim report on the National School Reform Agreement. The Commission’s inquiry, referred by the previous government, was “spurred in part by concerns that, despite the large increase in public funding since 2018, student outcomes have stagnated”.

It is not clear what is meant by “the large increase in public funding”. It is easy enough to add up Commonwealth and state appropriations and report an increase, but then come questions of an appropriate deflator to bring figures back to “real” terms (the CPI, an education wage cost index, or some wage cost index for equivalent work, in view of the labour-intensity of school education?), and then some divisor to account for a rising school-age population (per student, per high-school student in view of greater retention, some allowance for changes in student expectations?).

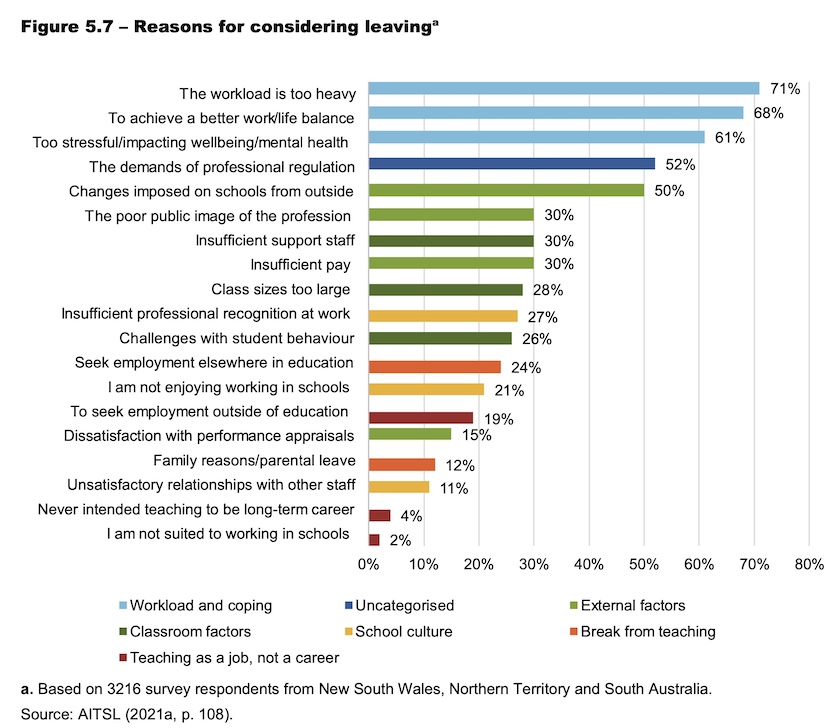

The report’s main concern is with the supply of teachers, and with ensuring that teaching remains (or becomes once again) an attractive profession. It notes that too much of teachers’ time is taken with non-teaching activities. Most notably it acknowledges the effect of high workloads on teachers, with consequences for both teachers and students. In this regard the findings of a survey it conducted on reasons teachers are considering leaving the profession are informative:

Note that pay is still a concern for 30 percent of respondents, and that although workload is clearly the main concern, pay and workload are not inseparable. Some people will accept a high workload if it is adequately remunerated.

The report notes the apparent decline in outcomes revealed in PISA and NAPLAN tests, and takes great care in examining the assumptions and methodology that go into these indicators. It has suggestions for better ways to track student progress, but rather than being too influenced by changing indicators, its concern is more with the shortfall in absolute outcomes, particularly for the “5 to 9 per cent of students struggling to meet minimum standards”.

There is a short (8 minute) session on the report on the ABC Breakfast program, where Patricia Karvelas interviews Jordana Hunter of the Grattan Institute: Teacher workloads holding students back.

The Commission invites submissions in response to this interim report. They should be made by October 21.

Refugees – the high cost of keeping people in misery

Mike Seccombe, writing in The Saturday Paper – ‘I am hopeless now’: Australia’s $9.65 billion torture camps – reminds us that there are still around 200 asylum-seekers, most of whom have been determined to be genuine refugees, held offshore in Nauru and Papua New Guinea. There are also another 1000 or so in Australia, not permitted to work and with no path to settlement in Australia. There is a trickle of people being resettled in the USA (probably the worst place imaginable for anybody needing health care) and as yet no one has been settled in New Zealand.

The Albanese government seems to be continuing the harsh policies of previous administrations, Labor and Coalition, and as Seccombe reports secrecy still prevails around offshore processing. In Parliament only independents – Secombe mentions Allegra Spender and Andrew Wilkie – are taking up their cause.

Gambling – at the top end of town and in the western suburbs

Gambling is in the news because of the report presented to the New South Wales Independent Casino Commission that found Star to be unsuitable to hold a casino licence. According to the government’s press statement (which includes a link to the report) “not only were huge amounts of money disguised by the casino as hotel expenses, but vast sums of cash evaded anti-money laundering protocols in numerous situations, most alarmingly through Salon 95 – the secret room with a second cash cage”.

Tim Costello in his role as an advocate for the Alliance for Gaming Reform reminds us that a bad report does not lead to a revocation of a casino’s licences. In his press statement he wonders “what criminal activity needs to happen under the noses of regulators before they lose their licence to operate”. Crown Casino, subject to similar revelations of wrongdoing, is still operating.

Criminal activity in the nation’s flashy casinos has been catching our attention in recent times, but we should not forget the less glamorous and more pervasive gambling that goes on in suburban pubs and clubs.

Charles Livingstone and his colleagues at the Monash University Gambling and Social Determinants Unit has just produced a report on recent gambling machine losses in five states (not including Western Australia and the territories). In 2021-22 a total of $11.4 billion was lost by people using gambling machines in these states.

That’s around $658 per adult, but not all adults use gaming machines. The losses per gambling machine user were $3 429 ($4 525 in New South Wales), and they were further concentrated in some of the poorer urban regions, such as Fairfield in western Sydney and Brimbank in western Melbourne.

In terms of what this money could otherwise have been spent on – the opportunity cost in econospeak – those losses are substantial. In Fairfield losses per adult were $2 519: we can imagine what that amount could have bought in private consumption to make life a bit easier, or in taxes to provide health care, education and urban infrastructure. Looked at from a broad economic perspective, Australia’s permissive attitude to gambling makes no sense.

But state governments tolerate casinos and poker machines because of their contribution to state revenue. Economists can demonstrate that if gambling were constrained to the levels permitted in other “developed” countries, there would be less poverty and associated problems, people’s incomes in the poorer regions would be boosted, and there would be more income tax and GST collected than is presently collected by state governments as gambling taxes. But those taxes would go to the Commonwealth, not to the states. Until we have substantial tax reform we will have casinos and poker machines.

The Tasmanian government has just announced that it plans to have a pre-commitment scheme to limit gambler’s losses. Industry spokespeople are already squealing in protest. The louder they squeal the more assured we can be that gambling venues have been heavily dependent on losses by addicted gamblers.

Ten steps to our emission reduction target

Now that we have legislation to achieve a 43 percent reduction in emissions by 2030, the Climate Council has put up a way to get on with the job: Power up: ten climate gamechangers. These are:

- Plug in 100 per cent renewables. (This is about investing in the national electricity grid).

- Boost batteries for rock-solid renewable supplies.

- Upskill Australians for clean trades. (A fancy way of saying we should invest in electrical and electronic skills.)

- Plan ahead for coal closures so no-one is left behind.

- Rev up fuel efficiency standards. (Or rev down?)

- Ditch diesel for renewable electric buses.

- Make new buildings net zero, and electrify established ones.

- Ensure major polluters do their fair share.

- End public funding and finance for coal, gas and oil.

- Develop a comprehensive climate and energy investment plan.

That’s a fairly cryptic list. Wesley Morgan of Griffith University, writing in The Conversation, has a more fleshed-out summary of those points.

The Climate Council stresses that there is no policy conflict between increasing our use of clean energy and addressing cost-of-living concerns. Both objectives can be met if we invest in the necessary infrastructure and skills.

Electric vehicles: if Californians can do it so can we

Australia’s local automobile retailers and repairers suggest that because we are starting a long way behind, and because we have shown a strong preference for big cars, we should go easy in a transition to electric vehicles.

Room for many more

Three academics from the University of California, Davis, consider these to be weak excuses. Writing in The Conversation – Australia is failing on electric vehicles. California shows it’s possible to pick up the pace – they point out that California and Australia are remarkably similar in terms of motor vehicle markets. In both markets there has been a preference for large cars and trucks. Drivers in Australia and California travel similar distances per year, and most trips are well within electric vehicle range – now around 450 km. We don’t have much charging infrastructure yet but that should not be a great impediment: most Californians charge their EVs at home.

The only impediment in Australia is the policy environment that is not supportive of EVs, particularly in its lack of vehicle emission standards.

The benefits EVs would bring to Australia are calculated by a group of researchers at the Swinburne Institute of Technology, who have done benefit-cost modelling of different trajectories of the rate of uptake of electric vehicles and summarized the results in The Conversation. Their “aggressive adoption strategy” would cost $152 billion and deliver benefits of $345 billion. It would also save 28 000 lives over the next 20 years because of lower exhaust emissions.

Covid-19 is still here even if we don’t want to see it

Independent member of Parliament and medical practitioner Monique Ryan is critical of the way governments, state and federal, are downplaying the seriousness of Covid-19. It’s as if by ignoring it we can wish it away. On ABC Breakfast she asks the government to re-think Covid management. She talks about the ongoing cost of long Covid, the general background of Covid work absences, and the risk of new variants arising for which we are not prepared. She warns of the consequences if we further relax already loosened isolation rules.

Readers may note that I am no longer providing graphs of the incidence of Covid-19. In keeping with the idea that if we don’t report Covid-19, it isn’t there, states have agreed to cease providing daily reports of Covid-19 cases, hospitalizations and deaths. Not that they have been serious about keeping the public informed anyway: on September 9, the last day of daily reporting, South Australia announced 63 Covid-19 deaths in one day, after a long period in which the daily death rate had been around 4. Most of these deaths had occurred between March and August, and hadn’t been reported. If members of the public don’t know how Covid is developing, how are they to make intelligent choices relating to vaccination, mask-wearing and social isolation?

If you’re missing my charts you may be interested in a set of charts of economic gains and losses over the Covid-19 pandemic, produced by the ABS. They plot the course of economic indicators, comparing them with trend lines of the same indicators. The general pattern, which will disappoint some armchair prophets who expected Covid-19 to presage the end of capitalism or the long-awaited dawn of the age of Aquarius, is that most indicators are heading back to trend. Profits are way up off trend, however.

And even if Australia isn’t keeping good data, the WHO still has its eye on Covid-19 globally. Its latest epidemiological update (September 14) shows an encouraging worldwide fall in Covid-19 deaths – a downward trend, with many bumps, since the peak in early 2021. Its global map shows that Australia still has a very high death rate. As we have been pointing out on this site, our death rate is high, but recent figures are almost certainly overstated due to the late reporting of deaths by state authorities (which means earlier figures were understated).

Journalists have seized on remarks by WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus who has said that the end of the pandemic is in sight, but reading his remarks in full, it’s more an exhortation not to slacken off than a celebration, and it includes a warning about possible new variants. Under-vaccinated populations are ideal incubators for new variants. On the ABC on Thursday night Mike Toole of the Burnet Institute noted that Australia still has a high Covid-19 death rate and echoed the WHO’s warnings. He repeated the observation that although we have a high two-dose vaccination level, our third dose level is low (72 percent of those who are eligible), our fourth dose is even lower (40 percent), and the pace of vaccination has slowed right down. (16 minutes)

Michael Toole and his colleague Brendan Crabb at the Burnet Institute write in The Conversation that imagining COVID is ‘like the flu’ is cutting thousands of lives short: it’s time to wake up. They are concerned not only about its high death rate, but also about its lingering effects on the lungs, heart, brain, kidneys and immune system – effects suffered by at least 4 percent of those infected with Omicron.