Other public policy

Gaslighting Australia

Santos Moomba gas plant: surely we have enough for our needs

Resources Minister Madeleine King has announced the release of 10 sites for oil and gas exploration in Commonwealth waters. They are in the Bonaparte, Browse and Northern Carnarvon Basin, off the northern Western Australia and Northern Territory coasts, and the Gippsland Basin off the eastern Victoria coast. Minister King’s media statement justifies the decision on the basis of securing gas as a transition fuel and securing our energy supplies.

The Australian Petroleum Production & Exploration Association APPEA welcomes the minister’s announcement, on the grounds that “our industry can continue to reduce emissions while ensuring future energy security”.

The Greens and independent Senator David Pocock are highly critical of the decision. Writing about the decision in the Sydney Morning Herald, journalist Nick O’Malley points out that the International Energy Agency has warned that the world cannot build any new oil and gas projects if it expects to meet Paris Agreement climate goals: Government releases 10 sites for oil and gas exploration, angering crossbench. Adam Morton, writing in The Guardian, reads King’s media statement as if it is “based on a bet that the world will fail on climate change”: Labor is sending mixed messages on energy – and some of it sounds like climate denial. As for the over-worked claim about a transition fuel, Morton suggests that there is a growing possibility that for our major population centres we will be able to make a rapid shift from coal to renewables, with only a small need for backup. (That would not negate the use of gas for short periods of peak demand, but that’s a minor requirement, for which we have plenty of gas on hand.)

The APPEA claim about reducing emissions is strange. Even if we take the morally dubious stance that whatever other countries do with our gas is no business of ours, extraction of gas involves fugitive emissions of methane – a greenhouse gas many times more dangerous than carbon dioxide – and the refrigeration of gas for transport as LNG is an energy-intensive operation. As for their concern with energy security, we are already the world’s largest gas exporter, accounting for 21 percent of the world’s gas exports. The problem lies in our failure to have reserved gas for domestic use – a problem in government regulation, not in resource availability, and it appears that the Commonwealth is moving towards implementing the Australian Domestic Gas Security Mechanism (AFR, paywalled). Richard Denniss deals with APPEA’s spurious arguments for expanding gas production in his June article Gaslighting Australia.

Mike Seccombe goes into the detail of King’s announcement in his Saturday Paper article How Labor is jeopardising its own climate target. He quotes King as asserting that this release of exploration permits would “support international energy security, particularly during the global turbulence caused largely by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine”. Really? Is the war in Ukraine expected to drag on over the years companies would take to drill exploration wells, verify supply, build drilling platforms, and build refrigeration and export facilities? Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is pushing up gas and oil prices in the short term, but it is also accelerating Europe’s transition to renewable energy and a corresponding enduring fall in the price of fossil fuels.

Fortescue Metals CEO Andrew “Twiggy” Forrest has thrown his weight behind the idea of banning new coal and gas development. In view of his company’s plans for investment in hydrogen, a cynic may accuse him of acting in self-interest, but that is to ignore the subsidies the fossil fuel industries enjoy, described by Richard Denniss in his Conversation article detailing their direct subsidies, and the de-facto subsidy they enjoy in not having to pay a price that accounts for their environmental damage (“externalities” in econospeak. ) These subsidies to the fossil fuel industries place hydrogen and other green investments at a competitive disadvantage.[1]

It’s hard to work out what has driven the government’s decision to keep on expanding opportunities for gas and oil exploration. Even if there were a secure market for LNG, there’s not much in it for Australia. Energy companies are adept at shifting profits offshore. As Denniss reminds us “four out of the five biggest gas miners paid no income tax at all in the seven years to 2020”, and because of deficiencies in our petroleum taxes, we collect far too little resource rent tax from gas. At most it could be said that if any new gas projects were to go ahead, our GDP would be boosted, but that’s only a statistical artefact because with profits flowing offshore it would do little for our GNI – our gross national income. Mike Seccombe suggests “The most charitable explanation is that Labor, having gone to the election saying it was not going to stand in the way of coal and gas projects, is operating on the expectation – or hope – that the market will decide against developing them”. Maybe Labor is still smarting from the hysterical reaction to the Rudd Government’s Resource Super Profit Tax. Confirming this possibility The Guardian’s political editor, Katherine Murphy, describes King’s efforts to keep the oil and gas industry onside: Federal Labor’s Madeleine King defends gas as “critical” to Australia’s needs. Or maybe the oil and gas companies simply want a few exploration permits they can count as “assets” on their balance sheets.

Carbon capture and storage as part of the deal

Besides the exploration permits, in another press release Minister King announces that she will shortly be finalising the award of offshore gas storage permits under the 2021 offshore Greenhouse Gas Storage Acreage Release.

The keyword in her statement is “offshore”. Carbon capture and storage is a wickedly expensive way to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. It may be economic in the production of cement, which involves burning limestone to produce carbon dioxide, but in general it is more economic not to produce carbon dioxide in the first place.

Peter Milne, writing in the Sydney Morning Herald – Carbon storage: climate cure or palliative care for fossil fuels? – quotes Woodside CEO Meg O’Neill as saying that the development of the Browse field is dependent on carbon dioxide, which is mixed with methane, being captured in the reservoirs. Otherwise the project is uneconomic. Milne points out that Chevron’s attempt to use carbon storage in its Gorgon project is working at half only its design capacity, and consequently the firm has had to buy 5 million tonnes of carbon offsets.

The emissions that would be captured in these storage projects are what are known as “fugitive emissions” that are associated with bringing gas out of its underground wells, but not the emissions from the energy used to refrigerate the gas.

Woodside and Timor Leste

Another gas development is the Sunrise project, operated by Woodside but 57 percent owned by the Timorese Government. In last weekend’s Saturday Extra Geraldine Doogue interviewed energy expert Saul Kavonic from Credit Suisse on the Timor Leste-Woodside gas deal. For the Timor government, bringing the gas ashore on its land in southern Timor is important because it would be a $10 billion industrial development for that very poor country, but Woodside claims that the project is economic, with benefits for Timor and Woodside, only if the gas is brought ashore at Darwin where there is already infrastructure. (13 minutes)

Most of the interview is about the Timor Leste Government’s commitment to developing Sunrise with a terminal on its own land, and its hint that it may seek help from China if Woodside or the Australian Government don’t come to its aid. Time is running out, because there is only a short period in which new LNG projects will be economic. A point easily overlooked is that if the Sunrise project, with proven reserves, has only a short window of opportunity, and cannot justify a new terminal, there doesn’t seem to be much hope for projects that are only at the early exploration stage.

1. Disclosure: I hold shares in Fortescue Metals in my superannuation fund. ↩

Other issues in the transition to renewable energy

Why did we break up those well-functioning state-owned electricity utilities?

The application of market fundamentalism to electricity markets has engendered the belief that governments, through breaking up and privatizing the old vertically-integrated electricity utilities, can simulate a competitive and thus efficient electricity market.

So writes Yanis Varoufakis in Project Syndicate: Time to blow up electricity markets. Application of the economists’ obsession with competition and their dictum that price should reflect the marginal cost of the least efficient producer, has not worked. Instead of providing an incentive for a transition to low-cost renewable energy, it has delivered a bonanza of monopoly profits to power companies at the expense of electricity users. Worse, in the public mind, those crippling power prices have come to be seen as a consequence of the shift to renewable energy.

Varoufakis is writing about Europe, where electricity price rises in the coming winter make our recent price rises look modest in comparison. His point is general, however. Our National Electricity Market was developed by people with too much faith in the abstract concepts of competitive markets, and with too little knowledge of the technologies and costs involved in electricity generation, transmission and distribution. In Australia we have pricing systems that are completely out of whack with equity and allocative efficiency. Electricity connection charges are too high (connection should be free because demand for connection is quite inelastic), and the “retailers” set per kWh usage charges that are the same for warming an electric blanket as heating a swimming pool (prices should be low for the first few kWh and then rise very steeply.)

If you think a Toyota Hilux is a gas guzzler, try a Bushmaster

Low emissions of past armies

If we were to measure the carbon dioxide emissions from the operations of our defence forces, the ADF would rank at #16 on the list of Australia’s biggest contributors, ahead of South 32, Alcoa, BHP, Fortescue, Shell, ExxonMobil and the major coal miners.

That’s a calculation by Martyn Goddard in his Policy Post contribution: In denial: Defence’s giant carbon footprint. He includes a number of tables on the fuel consumption of military equipment. The Bushmaster, for example, has a fuel consumption of between 50 and 200 liters per 100 km, and a tank almost has to be followed by a fuel truck. (Do the Ukrainians have to rely on Russian fuel for the Bushmasters we sent them?)

Gas guzzlers

But the real gas guzzlers are military aircraft, that dwarf civilian aircraft in their fuel consumption.

Goddard points out that the ADF reveals little about its carbon dioxide emissions or fuel use, but he is able to make some reasonably good estimates, using a range of data sources. His other main point is that even in peacetime the ADF is highly dependent on fossil fuels for its normal training operations. They don’t seem to be in any rush to electrify their vehicles.

Have we learned nothing from the fuel-supply line problems that beset the military forces in the 1937-45 wars?

National accounts – profits up, wages down

On Wednesday the ABS released National Accounts for the June quarter, showing a 0.9 percent growth in GDP over the quarter and 3.6 percent over the year to June.

Notably it finds that the wages-profit share of national income has moved decisively in favour of profits. Wages had been hovering around 50.0 percent of GDP for a few quarters, but in the June quarter they fell to 48.5 percent of GDP. This is the latest instalment in an erosion of wages’ share of GDP since its 55.2 percent high point in 2016.

The ABS identifies mining as the main source of profits over the last two quarters, confirming that the Coalition was certainly effective in its policy of suppressing wages and diverting income to the mining sector.

Over the last two quarters there has been some growth in nominal wages in the private sector, but very little in the public sector. Teachers, nurses and other public sector workers are experiencing not only an absolute fall in real wages, but also a fall relative to workers in the private sector.

There has been a net run-down of inventories, consistent with supply-side constraints.

Net trade – the excess of exports over imports – has contributed 1.0 percent to GDP over the quarter. In other words, without this boost GDP would have fallen a little, and as Treasurer Chalmers points out, mineral commodity prices have fallen in the two months since June.

For those seeking more than my selective summary, the ABS has an informative and readable website: 16 things that happened in the Australian economy in June quarter 2022.

Interest rates – The RBA pushes on

In raising interest rates by 50 basis points the RBA did not wait for Wednesday’s release of the national accounts, which were to dispel any notion of a general breakout in wages. Nor was it influenced by Monday’s figures on business indicators revealing a 28.5 percent rise in profits over the last year, contrasting with a 6.8 percent rise in wages – a standstill in real terms.

The RBA media release emphasised inflation as its overriding concern: “The Board is committed to doing what is necessary to ensure that inflation in Australia returns to target over time”, where that target is 2-3 percent.

Tightening monetary policy works by influencing aggregate demand, but it does nothing to dampen inflation resulting from supply-side constraints: indeed high interest rates can worsen supply-side inflation if it impedes productivity-improving investment. (The RBA Board is a collection of learned folk, but it includes no engineers.)

The RBA acknowledges that there are “capacity constraints in some sectors of the economy” and that “consumer confidence has fallen”, but it also notes that “there are some pockets where labour costs are increasing briskly”.

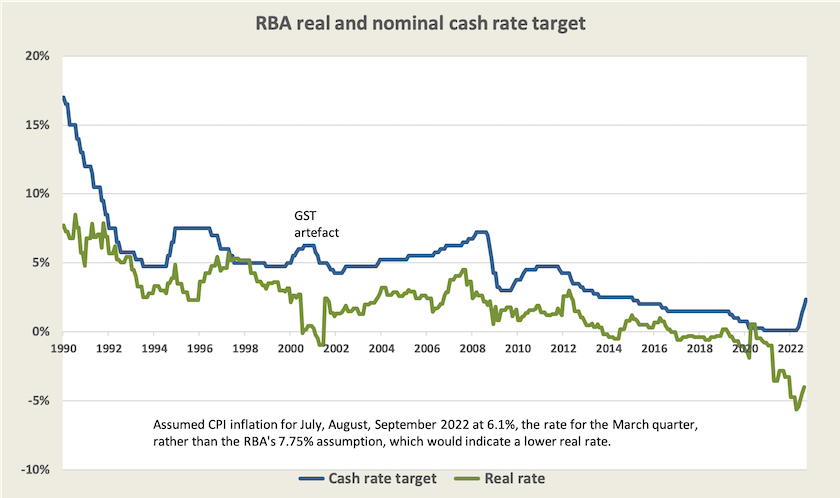

This latest rise leaves the real rate (after inflation) in negative territory, where it has been for most of the last five years.

If housing is to become affordable and if there is to be any progress in closing wealth disparities, positive real rates have to be restored, but some people believe the RBA should not be raising rates just now. Before the decision Greens Senator Nick McKim suggested the RBA hold off raising rates until after the October budget, and that the government should rein in corporate profiteering – essentially replacing broad-brush monetary policy with directed fiscal policy.

There are three other arguments for not raising rates too quickly. One is about the time lag for monetary policy to take effect, particularly when there are fixed-rate home loans to be rescheduled many months from now. In these roundups we have already used the metaphor of steering a big boat: it’s easy for the driver to apply too much rudder, not realising that the boat’s reaction is slow but strong. Martin North, of Digital Finance Analytics, in a 10-minute interview on the ABC’s Breakfast program, points out that the effect of an interest rate rise takes two to three months to show up in higher mortgage repayments and household stress. He estimates that around 1.7 million households may be facing severe mortgage stress (which he defines as negative household cash flow). When asked if the RBA has been too aggressive, he responds by pointing out that it should have been raising rates much earlier.

Another reason the RBA should hold off is the shock of the accumulated 2.25 percent rise in interest rates over five months. When housing rates were 8 to 10 percent in the late 90s and early 2000s, a 2.25 percent rise was relatively much smaller than when housing rates are as low as 4 percent, as they have been recently.

The third reason is that a moderate level of inflation, perhaps in the order of 4 or 5 percent, if allowed to pass through to nominal wages, relieves borrowers of the burden of their loans. Inflation is tough on lenders but easy on borrowers. In earlier times inflation has been an effective means towards cancelling debt, including the debt the Commonwealth accumulated during the Pacific War, and inflation reduced people’s housing debt in the 1970s. One may argue that such logic implies an injustice on lenders, but in a capitalist economy there is a good reason why people should do something more adventurous with their cash than putting it in cash or low-interest bonds.

Martin North says that the RBA is now conducting a high-risk experiment in using monetary policy to combat supply-side inflation. It’s hard to be confident in the RBA: its policy of holding rates so low for so long failed to stimulate either business investment or consumer spending, as the textbooks suggest. Conversely recent rate rises have not dampened consumer spending as cashed-up households return to the shops with pent-up demand. Such an observation is easy to make in hindsight: two years ago no one knew how the pandemic would play out. But it is a comment that the RBA is still in unfamiliar territory, and should be cautious lest it destroy the economy in order to save it.

Extracting information from the government is getting harder

The Centre for Public Integrity has researched the ease or difficulty in extracting information from the Commonwealth under Freedom of Information provisions.

In their media release, which includes a link to their detailed paper “Delay and Decay”, the Centre reveals that in the ten years to 2020-21 there has been a doubling in the proportion of FOI requests that are not handled within the statutory 30-day period, and a tenfold increase in the number of requests taking over 90 days. There has also been a large increase in the number of requests refused and only partially filled.

CPI director Geoffrey Watson says “FOI is an important aspect of our democracy. Without transparency of information, a culture of secrecy and corruption can flourish.”

Covid-19 – good news for now

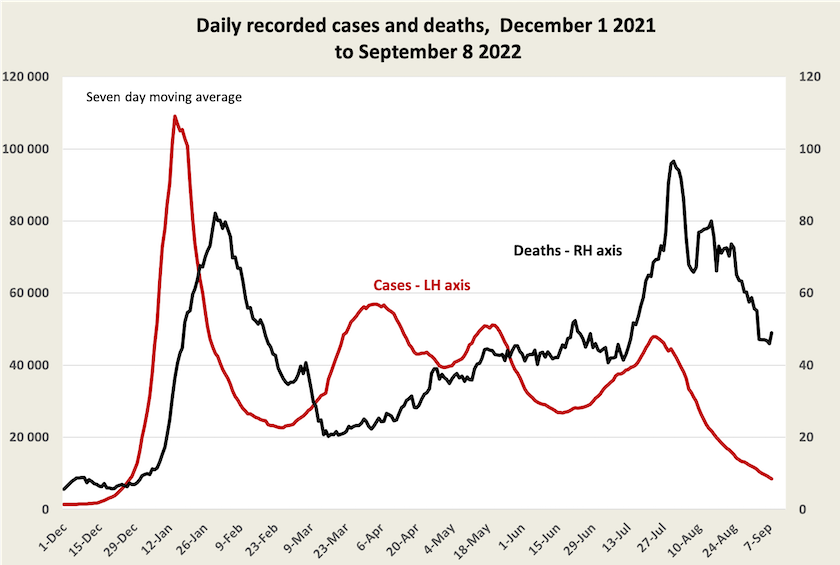

Recorded cases and deaths continue to fall.

At 1.8 daily deaths per million population, our death rate is still high, however, compared with other “developed countries”, where the rate is typically between around 0.8 and 1.4. Death rates are particularly high in Victoria, at 2.7 daily deaths per million.

Writing in The Guardian Nick Evershed suggests that the Covid pandemic may be causing more deaths than Australia’s daily numbers suggest, because it is difficult to ascribe the cause of death when there is co-morbidity, and there is a possibility that Covid-19 contributes to an increased risk of heart disease.

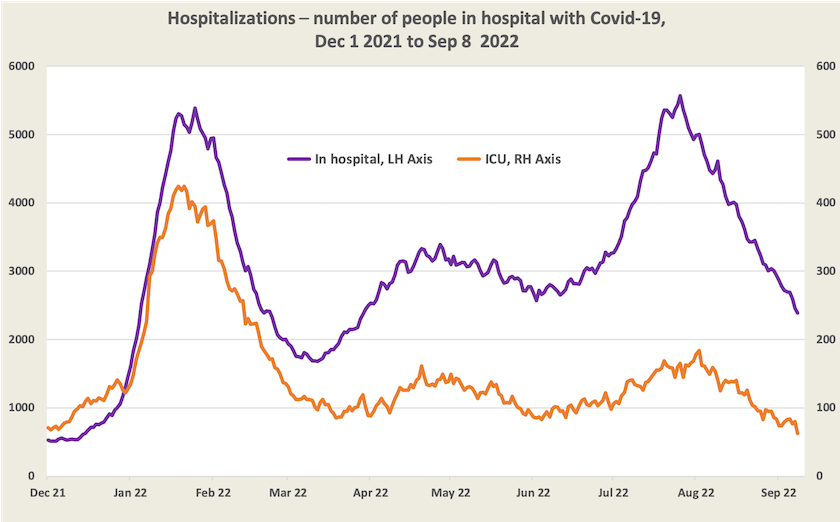

The number of Covid-19 sufferers in hospital and in ICU continues to fall.

Governments will no longer be collecting daily data on cases or deaths. In view of the serious undercount of cases, this is no great loss, but it means trends and turning points will no longer be easily visible. Death data has been generally accurate but lumpy because health authorities have been letting deaths accumulate before reporting them. Nevertheless it seems strange for health authorities to be easing off on reporting deaths when they are still running at about 45 a day, or 16 000 annualized – around 10 percent of deaths from all causes.

Vaccination

We achieved high levels of first and second dose vaccination – respectively 98.0 and 96.3 percent of the eligible population.

Uptake of third and fourth dose vaccination is a less encouraging story. Only 71.7 percent of the eligible population has received a third dose and 40.1 percent of the eligible population has received a fourth dose. The rates of vaccination have slowed to a crawl: at the present rate it would take 7 years for 100 percent third dose cover and 2 years for fourth dose cover.

Cover varies significantly by jurisdiction. The ACT has 80.2 percent third dose cover, while at the other end Queensland has only 64.8 percent third dose cover.

Paul Griffin of the University of Queensland, writing in The Conversation, reports on the development of Omicron-specific vaccines. The Moderna Omicron booster has been provisionally approved in Australia for adults aged 18 and over, but as yet supplies have not arrived and so far the Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation has not issued guidance on its use. He also outlines some expected vaccine developments in the future.