Other public policy

Those tax cuts clash with the government’s policy, but are they really so important?

It’s hard to find anyone defending the stage 3 income tax cuts – cuts that will see a 32.5 percent marginal tax rate applied to all incomes between $45 000 and $200 000. As the Australia Institute points out, most of the benefit will go to the top 10 percent of taxpayers, while the bottom 20 percent receive nothing. Peter Martin points out that they will send middle earners backwards and give high earners thousands.

When we have the problems of falling real wages and too much money in the hands of the well-off, sloshing money around and driving up asset prices, we don’t need tax cuts. Also they are fiscally costly: the Parliamentary Budget Office calculates that they will cost $16 billion in their first year (2024-25), with an accumulated cost of $184 billion over ten years. That’s a tough hit on a budget carrying a “trillion dollar deficit”. The Guardian gets across the point about the extravagance of these cuts by presenting 37 costed expenditure proposals – raising the unemployment benefit, increasing Medicare rebates, building a proper Sydney Melbourne railroad and so on – inviting readers to choose how they would spend that $184 million. The exercise is rough, in that it bundles capital and recurrent expenditure, but it gets the message across: these tax cuts come at a big opportunity cost in terms of forgone public services.

Much attention is focussed on the government’s insistence that it will not go back on its promise to retain the cuts, a promise Albanese repeated in his Press Club address on Monday. Although they were not in his prepared speech, they came up in the questioning. The ABC has a 2-minute clip of Andrew Probyn’s question and Albanese’s reply. Albanese’s response is strong in terms of Labor keeping its pre-election promises, but his argument is unconvincing.

The tax cuts go right against Labor’s espoused philosophy and political priorities. Some journalists are surmising that the government has no reason, right now, to break its promise: the cuts don’t come into effect until 2024-25 and there will be two budgets before then, in October this year and in May next year. The government can sit back for now, as pressure builds up for the cuts to be dumped.

That pressure is mounting. Liberal MP Russell Broadbent has added his voice to those of independent MPs calling for the cuts to be repealed. And so long as the issue stays alive it may be in Labor’s political interests to have Dutton pleading for the interests of the nation’s most well-off.

It is notable in Albanese’s speech that, while he spoke about the fiscal conditions shaping the October budget, he did so only in the context of the work of Cabinet’s Expenditure Review Committee. As its name implies, this committee is concerned only with expenditure: revenue is handled separately. It’s an arrangement designed around the Coalition’s obsession with capping taxes (at 23.9 percent of GDP), and forcing a policy focus on cutting expenditure.

In its zeal for reform of government processes, the government could be well advised to re-visit this process, and to consider revenue and expenditure proposals together, to break from the inherited assumption that taxes must be kept at X percent of GDP, where X is a figure based on something or other that has never been specified.

The tax cuts average out at a cost of $18 billion a year. In fact that’s small beer. As pointed out in the roundup of 23 July, Australia’s taxes (Commonwealth plus state), at around 28 percent of GDP, are close to the lowest of all high-income “developed” countries. If we lifted our taxes to 35 percent of GDP, around the level in the more moderately-taxed EU countries, we could be raising another $140 billion a year. That’s probably around the revenue we need to bring our public services up to scratch, to provide decent social security benefits, and to reduce Commonwealth Government debt.

In any event it is not clear that the focus of tax reform should be on one aspect of personal income tax. As Shane Wright writes in the Sydney Morning Herald – Tax cut debate sells the country, the economy and the future short – “the problem is the entire tax debate has narrowed to elements of the income tax system. It’s now devoid of important economic and budget issues around tax”.

We have a worsening problem in achieving an equitable distribution of the benefits of economic activity, but the deepest and most rapidly-widening inequities are in wealth and life chances, not in income.

Even within our income taxes, however, there are indefensible inequities relating to tax allowances for so-called “self-funded” retirees, whose pension benefits are not subject to normal income tax. Then there are inequities to do with concessions for family trusts, and a capital-gains tax system that gives concessional treatment to short-term financial speculation while relatively penalizing long-term investment.

In fact there could be a justifiable case for retaining a flat tax for incomes over a wide range ($45K to $200K), because a progressive income tax with many steps is most suited to an economy where people have a steady or rising income, year to year. That is not the economy that’s emerging, where many people’s incomes, through choice or happenstance, can change significantly from year to year. Women in particular tend to be subject to highly fluctuating incomes.

It may be a good idea for the government to let the income tax cuts go through to the keeper, while it pursues the more serious work of fundamental tax reform to restore our emaciated public services.

Should superannuation be used for nation building projects like social housing?

That’s the title of a 21-minute segment on last week’s Saturday Extra, where Geraldine Doogue discusses whether superannuation funds should be directed to invest in projects that the government sees to be economically beneficial. Her guests are University of New South Wales economist Richard Holden and Matthew Linden of Industry Super, the coordinating body for 12 industry superannuation funds.

A little public finance theory helps clarify the issues they discuss. Many investments undertaken by government pass muster on cost-benefit grounds but they don’t provide enough income to make them worthwhile for private investors: they are economically viable but not financially viable. Public housing is a case in point. If it achieves its purpose of making housing affordable for those with low income, it probably won’t provide enough cash flow for investors. Its economic benefits will be diffuse, manifest as savings in health care and social security assistance and in providing better-functioning communities – “positive externalities” in econospeak. These benefits flow to the community at large, but not in identifiable cash flows.

It would be a major intervention by the government to require superannuation funds to make such unprofitable investments – essentially an appropriation of private capital to do what the public finance system has neglected to do, or a “privatized tax”. In the discussion Holden and Linden understandably argue against such an intervention, but they are open to the idea of governments subsidizing such investments so that private capital, as may be provided by superannuation funds, can achieve a reasonable return.

Such investments are likely to be unexciting but reasonably secure. It is in the interest of their members for the superannuation funds to have a diversified portfolio of assets ranging from high-return-high-risk through to low-return-low-risk. Infrastructure assets can be an ideal means to provide that security buffer.

Climate change and energy

The RBA on climate change risk

One notable feature of Commonwealth budget papers is that their statements of risks make no mention of climate change. (Will it be different in Chalmers’ budget in October?). The Reserve Bank, however, has been upfront about Climate Change Risk in the Financial System in a speech by Jonathan Kearns, Head of Domestic Markets.

He presents by now well-known data on climate change, and identifies three categories of risk associated with climate change. There is an increasing incidence of acute physical risk – damage to assets resulting from fire, flood and other disasters. There is chronic physical risk – loss of the productive capacity of farmland for example. And there is transition risk – “risks resulting from changes to policies, technology and people's preferences that are brought about by climate change”.

He goes on to describe how financial analysts have developed a risk model (the Climate Vulnerability Assessment) to model combinations of physical risk (not controllable by government) and transition risk (influenced in large part by Australian and foreign government policies). Transition risk can be reduced by having clear, stable and well-communicated policies.

AEMO on electricity supply: blackouts or investment opportunities?

The Australian Energy Market Operator’s 2022 Electricity Statement of Opportunities can be read in different ways – as an assurance that we have plenty of electricity to see us through 2022-23, as an invitation to investors (including the government) to take advantage of opportunities to invest in new assets as aged coal-fired stations close down, as a warning of a future of blackouts, or as an indictment of those policymakers who for ten years have deliberately impeded our energy transition.

To quote its summary:

This 2022 ESOO signals a need to urgently progress anticipated generation, storage and transmission developments, including ISP [Integrated System Plan] actionable transmission developments, to support the energy transition underway. With the NEM [National Electricity Market] expected to experience a cluster of five announced coal-fired generator retirements in the next decade, and needing resilience for potential future closures as well, the investment need is pressing and widespread across the NEM.

It’s worthwhile giving the document a quick glance so as to appreciate its scope, because it deals with multiple and interacting uncertainties. How reliable will the old coal-fired stations in New South Wales and Victoria be in their final years? Will the government get cracking on investing in transmission lines to link our renewable resources, as outlined in the ISP? Will households and businesses continue to invest in distributed (“rooftop”) solar? Will the general economic environment – cost of capital, fiscal and monetary settings – be favourable to investment? Will real resources – engineers, technicians, equipment – be available?

Those are some of the uncertainties on the supply side. On the demand side there are many more. What will be the rate of immigration? How will electric vehicles affect the NEM – as challenging new sources of demand, or as means to stabilize demand? How will consumers react to already-announced changes in prices, and will tariffs set by “retailers” act to allocate scarce resources efficiently or to maximize their profits? Will consumers invest in batteries and adopt demand-side technologies to reduce peak demand? How will climate change affect both supply and demand? An illustration of how the AEMO is considering these uncertainties is on Pages 25 to 29 of the report where consumption forecasts are modelled.

Any journalist or politician who latches on to this document to claim renewable energy is not up to the task is misreading it. Its baseline assumptions are conservative, and it identifies huge opportunities for investors.

Utes and trucks

Speaking on that usually impeccable news channel Sky News, deputy Liberal leader Sussan Ley noted that “no one in the world is making an electric ute, by the way, and even if they were it would be unaffordable”. In its factcheck of Ley’s statement, the ABC came close to breaking its rules prohibiting commercial advertising, as it listed several electric ute manufacturers, and gave some indicative prices. EV Council CEO Behyad Jafar called her statement a monumental blunder. Politicians are mortals who make mistakes, but within the Coalition ranks there seems to be a deliberate policy to ridicule any moves to decarbonize the transport sector.

Pre 2003. now zero emissions

On a different but closely-related issue the Grattan Institute has established a case to ban old trucks (pre-2003) from our densely-populated biggest cities, a practice in many cities that have designated low-emission zones. Australia has a particularly old fleet of trucks: 14 percent of our trucks are pre-1966, emitting “60 times the particulate matter of a new truck, and eight times the poisonous nitrogen oxides”. According to the report emissions from trucks kill more than 400 Australians each year, and contribute to chronic respiratory illnesses.

On the ABC PM program Gavin Coote interviews Marion Terrill of the Institute on the report. A trucking industry lobbyist argues against such a ban because there is a current worldwide shortage of trucks – a lame reason in view of the temporary nature of the shortage – and an owner of 70 trucks says he has no trouble in keeping his fleet updated. (6 minutes)

The issue illustrates that reducing greenhouse gases is not the only environmental issue facing the transport sector, but moves to reduce GHG pollution will probably have other benefits. Indeed, filthy black smoke emanating from a tailpipe is likely to promote a stronger reaction from the public than emissions of invisible and odourless carbon dioxide. It also illustrates a general point that in some sectors larger companies are more able to take the energy transition in their stride than smaller businesses.

Sexual violence: it’s more prevalent than we may believe

Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety has produced a confronting report on the incidence of sexual violence. You can get to the report through ANROWS’ media release, or you can skip the menus and download it directly.

The researchers found a surprisingly high incidence of sexual violence: 51 percent of women in their twenties reported having experienced sexual violence at some time, while older women reported lower, but still high lifetime experience of sexual violence. This age gradient suggests that either sexual violence is becoming more prevalent, or that younger people are more likely to classify incidents as sexual violence than older people do in their recollections. It is notable that ANROWS uses WHO’s broad definition of sexual violence.

Women who experienced sexual violence in childhood were more likely than other women to experience sexual violence as adults, as were women with lower levels of education, and women who identified as bisexual or homosexual.

The report’s public policy recommendations are mainly around supporting and protecting women who have suffered or are at risk of suffering sexual violence. The only mention of policies to prevent sexual violence focuses on women’s behaviour, for example in relation to use of alcohol and other drugs. Considerations of men’s upbringing and behaviour, and issues such as the valorisation of violent sports, are not covered.

Covid-19 – waning, for now

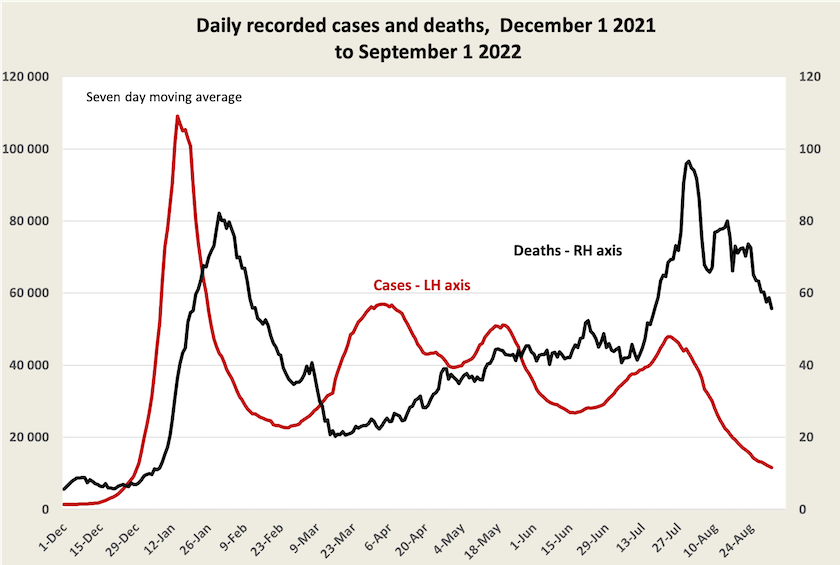

Figures on cases and deaths look promising. To repeat the usual qualification, cases are under-reported, and that under-reporting is becoming more significant as cases go undetected and as people don’t bother reporting cases, but at least they suggest that infections probably peaked around the last week in July. Deaths get recorded, but the timing of death is unreliable: for example this week the New South Wales Health Department reported that not all the 37 deaths recorded on Monday occurred “in this week”, and in Queensland it appears that no-one is allowed to die of or with Covid-19 on a weekend. Because of these recording lags, the actual decline in deaths has probably been more marked than is suggested by the graph.

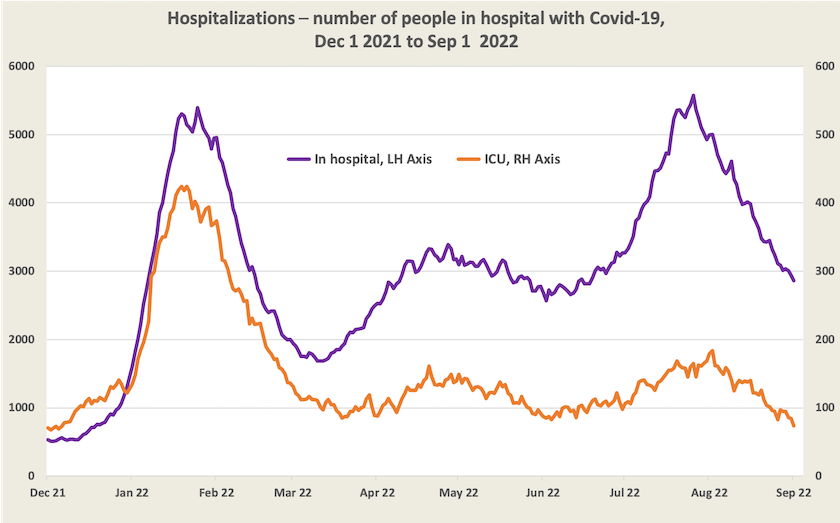

More reliable up-to-date indicators of the severity of Covid-19 and its load on hospitals is given by data on the number of Covid-19 sufferers in hospital and in ICU. These are clearly on the way down. Also it is notable from the graph that earlier this year for every 1000 people in hospital with Covid-19 around 8 were in ICU. Now only around 3 in every 1000 are in ICU.

Does this mean we can slacken off? Maybe, but only carefully

Much publicity has been given to the relaxation of isolation rules and abolition of the requirement to wear masks when travelling by air.

The AMA has criticized the shortening of isolation periods, and has made the reasonable demand that the government release the health advice upon which the decision was made, but, like its predecessor, the Albanese government is parsimonious in providing the public with information on Covid-19.

In a move reminiscent of George Bush’s “mission accomplished”, the Queensland government has declared that the state has passed its third Omicron wave, has removed a number of vaccine mandates, and will be cutting back on its already limited reporting on cases and deaths.

On the ABC Breakfast program on Monday Gerard Hayes of the Health Services Union presented a convincing case for Covid isolation rules to be scrapped altogether. Some people have a mild dose of Covid with a short infectious period, while others may have Covid for more than a week: a one-size-fits-all should not apply.

He noted that people’s experience with Covid has raised awareness of the cost of soldiering on at the workplace with an infectious disease. There have been sensible changes in people’s behaviour, such as working from home where possible, and not sitting in a GP’s waiting room infecting everyone else in order to get a sick certificate. But many managers have shown less adaptability. (It’s a strange workplace that puts more trust in the words of an unknown GP than in one of its own staff.)

The Health Services Union has a valid point. Because people rely heavily on RAT tests, which often give false negatives (but fewer false positives), and because more people seem to be getting asymptomatic cases, it is likely that many people will be going to workplaces, universities and social gatherings unaware that they have Covid-19. At some time there will have to be less reliance on test results and more reliance on norms of good social behaviour.

Let’s not forget vaccination

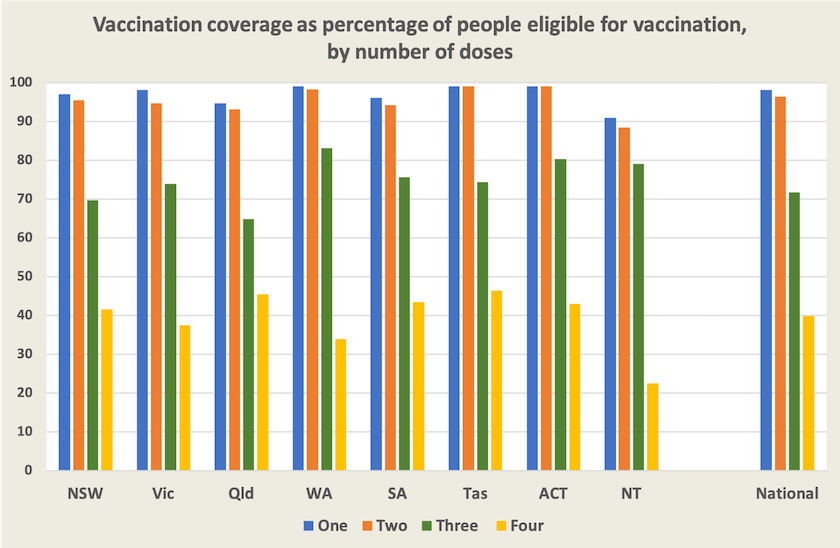

With all the attention on isolation periods and mask mandates, it is important to remember that while 98 percent of adult Australians have had two doses of vaccines, only 72 percent have had a third dose (65 percent in Queensland), and only 40 percent of eligible adults (>30 years old) have had a fourth dose.

Also it is evident from Health Department vaccine rollout reports that the rate of vaccination has slowed to a crawl in the last few weeks.

There may be sound reasons for shortening isolation periods, but there is the risk that the public will interpret this change, and the Queensland government’s relaxed approach, as a message that Covid-19 is no longer a menace. But there is still a large vaccination gap, and even though for most Australians the risk of severe illness or death may be receding, there are many people with compromised immune systems for whom the risks are serious. Also there is the risk for everyone of long-term debilitating effects of Covid-19.

We cannot eliminate Covid-19, but we should be taking all reasonable steps to suppress it.

Food and public health

In the last week or so diet seems to have come back on the agenda. In the context of cost-of-living concerns, ABC journalists in north Queensland, disturbed by the prevalence of diabetes in remote communities, remind us (once again) that processed carbohydrates such as rice and pasta are much more affordable than fresh fruit and vegetables.

Crispin Hull reminds us that last week was sugar-awareness week, and urges us to follow the example of countries that have imposed a sugar levy on drinks – a levy that’s much more effective in reducing child obesity that easily-circumvented labelling laws.

The Australia Institute has conducted a survey on people’s attitudes to TV advertising. Of those surveyed 66 percent believed that junk food advertisements should be banned during children’s viewing hours, and 51 percent believed that alcohol advertisements should be banned on TV. There was even stronger support (71 percent) for a ban on gambling advertisements.

Such regulations would surely be in the public interest because of their savings in health and social security costs.