Health policy

The pandemic in pictures

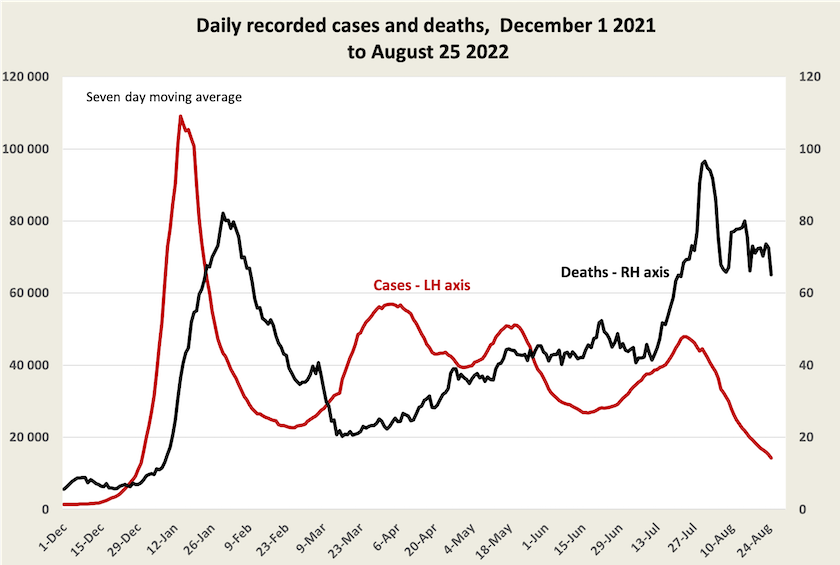

Even with smoothing (lagging average over 7 days) death data is daggy, but it does appear that our daily death rate is falling. Once again the caveats: death data is probably accurate, but some states allow numbers to accumulate before reporting them, while case data is probably subject to significant under-estimation, and becoming more so.

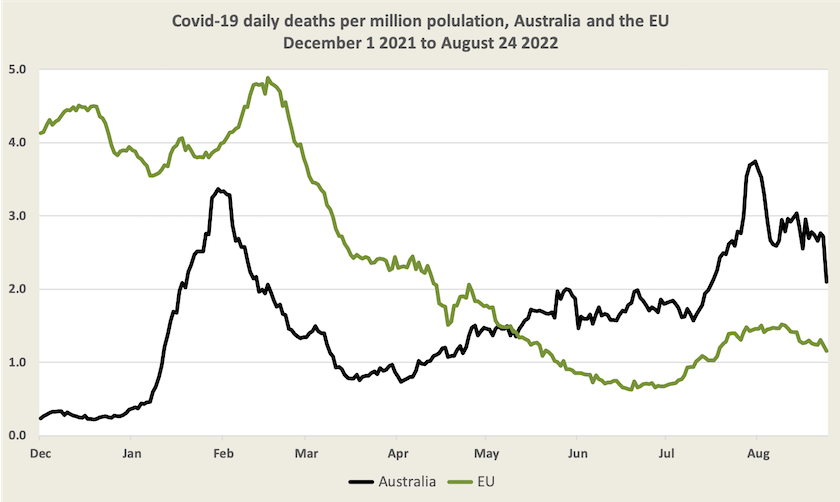

Our daily death rate is still high in comparison with Europe’s.

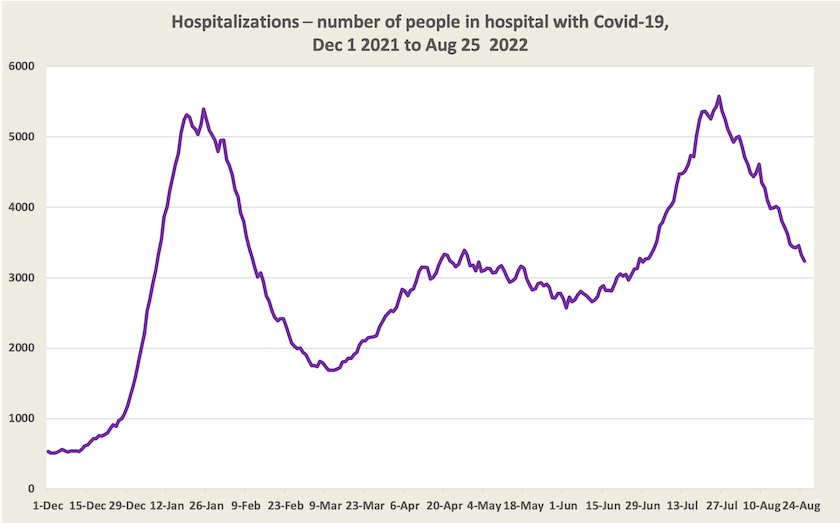

The number of Australians in hospital with Covid-19 is coming down.

Other winter pestilences

One reader has brought to our attention the Flu Tracking Participant Newsletters. Because there is no definite way of identifying influenza, the newsletter reports on the incidence among its respondents of “runny nose and sore cough”, and “fever and cough”.

It has been a bad winter in both these categories. A glance at their graph shows “fever and cough” (a rough indicator for influenza), has been peaking at the same times as the Covid-19 Omicron peaks, suggesting strongly that many people are contracting Covid-19 and interpreting it as influenza. (Note that RAT tests, while rarely giving false positives, often give false negatives.) The good news is that these respiratory illnesses are on the way down.

One significant figure is that over May to July, around 1.5 percent of respondents reported having a fever and cough and taking two or more days off normal duties. That has now dropped to around 0.5 percent and is still falling. Because these figures relate to the 89 000 participants in the flu tracking project they may reflect some selection bias, but they help explain the high rate of absences and associated business disruptions in recent weeks.

Economic and political reflections on Covid-19 in Australia

Economists

Joe Walker’s Jolly Swagman podcast has a long discussion with two economists, Richard Holden and Steven Martin, titled The Race that Stopped the Nation. The podcast is two hours, but there is a transcript provided. They accept that the pandemic has challenged economists to re-think their views on trade-offs and risk-benefit calculations.

They believe that in spite of the Commonwealth’s poor performance on ordering vaccines, we have come through Covid-19 (so far) very well in comparison with other countries, and they speak positively of the flexibility shown by the Treasury Department and Treasurer Frydenberg, for accepting that it was necessary to do what it takes to deal with the pandemic.

Politicians

Even Morrison’s harshest critics acknowledge that there may have been some justification in his taking on the health portfolio role in the early days of the pandemic, although they rightly criticize him for his secrecy around the decision and they point out that the dual appointment was unnecessary, even in the face of what could have been a far worse situation.

The ABC’s Andrew Probyn describes how Morrison took on the health portfolio, with advice having been offered by Attorney-General Christian Porter: Scott Morrison's power grab was set up by a handful of senior Coalition MPs — but none of them knew what would come next. The rest is covered in the Solicitor-General’s report.

The GP shortage explained

It will take time to relieve the GP shortage, but all we need to do is to get more students studying medicine.

Wrong.

In fact in comparison with other “developed” countries we do reasonably well for medical graduations. The trouble is that on completing their MBBS, graduates find there are more financially appealing career options than general practice, including further study to become specialists. In 2013 469 medical graduates became GPs, but in 2021 only 252 did.

This is one of the revelations in Martyn Goddard’s Policy Post: How the GP crisis happened – and why it will get much worse. Goddard describes what has led to this situation, particularly the government’s squeeze on Medicare rebates. The consequences are delays in seeing GPs, particularly in non-metropolitan regions, unnecessary presentations at hospital emergency departments, and high co-payments by patients. He also looks at indicators that support government claims that “bulk billing” rates are rising. They are indeed, but that’s to do with items direct-billed, not consultations. Use of these direct-billing figures to make political claims is a “scam” Goddard explains.