Public policy

Real men don’t drive electrics, or why electric cars need a nudge

Here is a quick thought experiment. Imagine you are buying a new car. Two models are on offer, identical in all aspects other than fuel efficiency. One model has a fuel efficiency of 11 liters per 100 km, about the average for the Australian fleet, while the other has an efficiency of 7 liters per 100 km, but is $5 000 more expensive. Which do you choose?

It’s a fair bet that most people will go for the cheaper car, even though, based on figures for average car use, car life, gasoline price, and their cost of finance, there is an $8 000 fuel saving in going for the more expensive car – an overall saving of $3 000.[1] In fact it’s unlikely that many people, other than a few retired nerdish engineers addicted to spreadsheet modelling, will bother to calculate the savings.

So twentieth century

The findings of behavioural economics suggest that when we have a choice involving upfront costs that yield savings over time, even if these savings are substantial, we go for the cheaper immediate outlay.[2] It’s the same bias that sucks us into buying a cheap printer with outrageously expensive ink. It’s because we recognize that weakness in our own decision-making that we accept the idea of compulsory superannuation.

That is the context in which the government has decided to review fuel efficiency standards, with a view to making electric vehicles (EVs) more affordable in comparison with traditional internal-combustion (IC) vehicles. With more stringent fuel standards, even those who, for reasons of range perhaps, cannot buy an EV yet, will still have an incentive to buy a more efficient IC vehicle.

On last weekend’s Saturday Extra Geraldine Doogue discussed the political, technical and economic contextof the government’s move towards mandating fuel efficiency standards with Helen Rowe of Climateworks and Marty Andrews of Chargefox. Because Australia has been almost the only “developed” country without fuel efficiency standards (the other is Russia), we have been a dumping ground for fuel-inefficient vehicles.

When we had a car manufacturing industry our lack of standards was an indirect form of protection for our manufacturers, but even though manufacturing ended in 2017 the Coalition government refused to introduce standards. Now, however “we’re in the most positive federal political landscape we’ve been in in Australia for EVs for a long time” as Andrews puts it, and the industry has generally welcomed the government’s move because it gives car importers and firms providing charge stations some certainty.

With fuel efficiency standards, and other nudges from the federal and state governments, we can expect the market for EVs to show rapid growth from its present low base.[3] Hybrids will probably phase out, perhaps a little later than IC vehicles.

In the longer term there will have to be policies relating to trucks and buses, and governments will have to devise ways to recover road use costs, including congestion, from EV users.

Also the whole motor vehicle maintenance industry will face serious challenges. The internal combustion engine, with its mechanical complexity, metal-on-metal moving parts, and its narrow speed-torque performance, has spawned a massive industry to maintain engines and drive trains, and has provided employment for thousands of skilled mechanics. EVs are mechanically simpler (therefore likely to be longer-lasting) and require a completely new set of skills for their maintenance, including skills in electronics and programming.

That’s about EV users. Also there are opportunities for Australia not only in the raw materials for EVs – we have all the necessary minerals – but also in value-added, at least up to the point of manufacturing batteries for a world market. But as Shannon O'Rourke of the Future Battery Industries Cooperative Research Centre points out in an article by the ABC’s Daniel Mercer, “time is running out for Australia to play a leading role in the battery value chain”: As EVs drive a mining revolution, will Australia become a battery minerals superpower?. Will batteries be another lost opportunity, victim of our tax system that encourages get-rich-quick speculation while penalizing long-term investment?

The Coalition’s contribution to the EV transition so far has been to bleat about “Labor’s broken promise”. Is that all it can do? Surely there will be many issues around re-training, road user charging and policies to do with adding value to raw materials that a political party, seriously concerned with public policy, could address.

1. Assumptions are a car life of 10, years, a gasoline price of $1.80/liter, annual distance travelled 13 000km, cost of finance 4.5 percent real. That 4.5 percent is a typical opportunity cost for someone with enough liquidity to invest. The cost for a borrower taking a car loan may be 7.0 percent real, but even at that rate the present value of the saving is $7 000. ↩

2. Economists have given this departure from rational self-interest the name “hyperbolic discounting”, even though it has little relationship to hyperbolae. ↩

3. EVs are subject to “network effects”, which means growth proceeds slowly until people realize that there will be adequate provision of charging points and service facilities, at which point demand takes off in a logistic curve. ↩

Employment, unemployment and wages

In the 1961 federal election Menzies was almost thrown out of office because the unemployment rate had crept above two percent. Only a strong preference flow from the Communists saved him. Now any unemployment rate below five percent carries bragging rights for the government.

Last week the ABS recorded July’s unemployment rate of 3.4 percent, the lowest since 1974 and down another 0.1 percent on June’s rate, the fall being partly because of a lower participation rate.

Over the last 30 months, with the disruption of the pandemic, it’s been difficult for economists to make any observations on longer-term developments in employment and unemployment, but as Covid-19 recedes (at least for the time being), they are starting to find trends and make cautious predictions, and even the ABS is cautiously resuming publication of trend series.

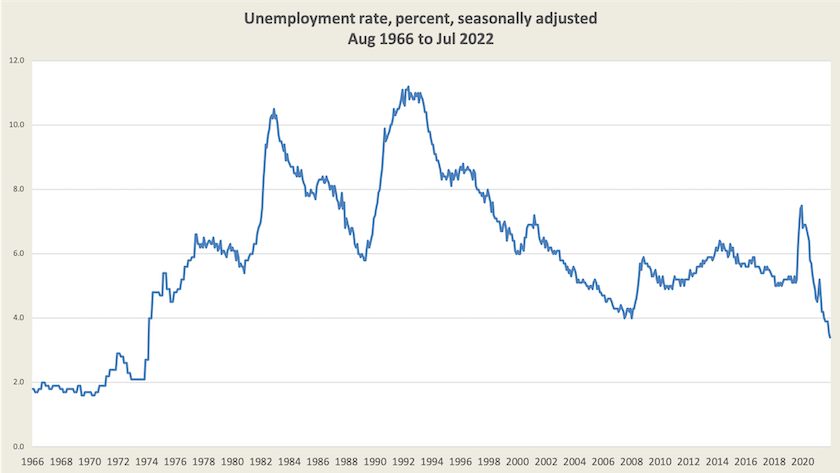

Peter Martin, writing in The Conversation, believes that unemployment is set to stay below 5 percent for years to come. He explains his optimism, in part, by the pattern of unemployment over the longer term, shown in the graph below:[4]

In past times, in response to economic shocks there were sudden surges in unemployment, followed by painfully slow recoveries, but in this century the surges have been less severe and the recovery has been more rapid – compare the lumps in the graph before and after 2000. He credits the Reserve Bank for having made rapid monetary responses to the shocks of this century, particularly the GFC and Covid-19. Economic shocks will result in unemployment, but if people can be brought back to work quickly we are protected from the “scarring” effect of long-term unemployment.

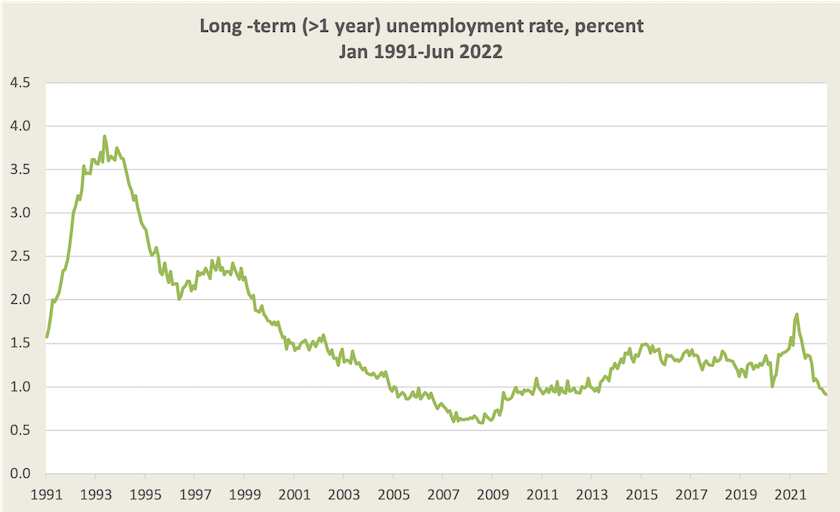

Gareth Hutchens, writing on the ABC website, takes up where Martin leaves off: Long-term unemployment is falling rapidly, and it's changing lives. Those who have been out of work for a long time – possibly years – are the most scarred. The longer one is out of work the harder it is, for many reasons, to get back to work. Hutchens notes that during this century so far there has been a significant fall in the long-term (> 1 year) unemployment rate, and a steep fall in long-term unemployment in the post-pandemic recovery.[5]

Ross Gittins is another who believes that our low unemployment will be sustained. He too notes that the rate of long-term unemployment has fallen in the post-pandemic recovery. The general pattern in the past has been for employers to turn to immigrants to fill labour shortages, but this time, with the borders having been closed, employers have turned to unemployed Australians, including the long-term unemployed. Gittins believes that the labour market in Australia is changing: he foresees a world where workers gain the upper hand. This is because of domestic demographic factors – we’re ageing – and even if we open up to immigration it will be difficult for any government to use immigration to suppress wages, because there is a worldwide demand for skilled labour.

Nevertheless some business lobbies are pressing the government to allow more immigrants into Australia. They seem to be aware that this government will not be encouraging unskilled immigrants, but business lobbies are still seeking to see more skilled immigrants brought into Australia. Crispin Hull analyses that argument – Skills shortage plea is a sham – pointing out that many so-called “skilled” immigrants are actually semi-skilled, and do nothing to alleviate the shortage of highly-skilled workers. In fact, because they add to aggregate demand, they may worsen it. Hull sees the solution in raising the pay of skilled workers whose real incomes have fallen because of government budget cuts – teachers, GPs and nurses.

One may ask if unemployment is so low, and demand for labour is so high, why aren’t wages rising? ABC journalists Michael Janda and Rhiana Whitson ask this question when they find that wages fall further behind the cost of living as pay rises lag surging inflation.

In a short (2-minute) clip – Unemployment has fallen rapidly but real wage growth remains suppressed – Alan Kohler explains the basic dynamics of the labour market. In part it has to do with the Coalition’s success in suppressing wages, but the fall in real wages from 2013, when the Coalition was re-elected is “largely coincidence”. He attributes effective wage suppression to earlier policies by the Howard government, which are still in force. In recent times wages have stalled, private investment has dried up, and profits have risen. Our present government may be less hostile towards wage earners, and employers are coming to realize that to attract and retain workers they may have to improve pay and conditions, but there can be a long lag between policy interventions, changes in demand for labour, and changes in wages. In the absence of industry-wide bargaining, pay rises in the private sector tend to occur through workers changing jobs and employers, a process that takes time, and in the public sector pay rises come through the slow process of the Fair Work Commission.

In the short term much depends on the Reserve Bank’s monthly moves, and Kohler expects the RBA to prioritize suppressing inflation, even if this increases the probability of a housing crash.

In the medium term much depends on the extent to which there will be reforms emanating from the “jobs and skills” summit. The ACTU is pushing for a move towards a return to collective bargaining, while some peak business lobbies seek to see only minor changes to the existing enterprise bargaining system.

In a perfect market collective bargaining and enterprise bargaining should produce the same outcomes, but the market is far from perfect: reliance on enterprise bargaining leaves many workers behind. Free market economists claim that underpaid workers can find employment in firms paying higher wages, but that’s not how it works. There are many impediments to such movement, including workers’ investments in firm-specific skills, their accumulations of sick and long-service leave, their lack of knowledge of opportunities, and the possible need for re-location. In industries dominated by small businesses subject to high competition, individual enterprise wage increases are almost impossible to achieve. Minister for Employment and Workplace Relations Tony Burke has expressed some interest in multi-employer bargaining.

4. Data from ABS special series Historical [labour force] charts from August 1966 to July 2022. ↩

5. Data from ABS Labour Force, Australia, Detailed. ↩

More advice for the Reserve Bank, but are they listening?

The next RBA Board meeting will be on Tuesday September 6, a day before the ABS releases the June quarter national accounts, and before the ABS formally commences its monthly CPI series (a stripped-down version of the quarterly CPI).[6] In view of the uncertainty around the economy’s short-term direction, it may be wise for the RBA to hold off doing anything for now, even though central banks in other countries, particularly the USA, have been raising rates rather aggressively.

The ABC’s David Taylor, drawing heavily on the view of former RBA board member Warwick McKibbin, believes that the Reserve Bank doesn't have enough information to make accurate interest rate calls. It’s not just about the timeliness of data: it’s more about the bank’s interpretation of that data: “the Reserve Bank's understanding of the main drivers of inflation is incomplete and has led to policy error.”

Writing in The Saturday Paper Mike Seccombe asks if the RBA really understands what’s driving price rises and if it clearly understands how it should respond: Where Australia is going wrong on the economy. The RBA’s established approach of raising interest rates in response to inflation is probably appropriate when there is an established cycle of rising prices and rising nominal wages – the textbook case of demand-pull inflation. But our current situation is very different: many price rises are a result of supply-side disruptions, and a large part of our demand-side inflation is due to pent-up demand and delayed spending during the pandemic, essentially a one-off phenomenon.

6. Some media have already seized upon a figure of 6.8 percent as the ABS’s estimate for CPI inflation in June, but this is highly qualified, more for illustrating how the monthly series relates to the quarterly series than providing a policy-relevant estimate of inflation. ↩

The indiscretion of discretionary grants

Two months before the election this year Prime Minister Morrison took personal responsibility for allocating $828 million grants to firms under a scheme known as the Modern Manufacturing Initiative. Sydney Morning Herald journalist David Crowe reports that more than half of the 17 recipients were in Coalition electorates and in other electorates that the Coalition considered to be contestable.

It would take a forensic investigation by the Australian National Audit Office to determine whether there was any political bias in funding. Maybe there is a concentration of innovative firms in Coalition electorates, but the main issue is that the prime minister took over control of grant allocation from the relevant industry minister. Also in this case, while the government was in haste to tell these 17 successful applicants that their grants were approved, others were been left in the dark: were their applications rejected or were they still being processed?

The more basic concern is whether any grants program should be designed in a way that gives a minister discretion over which projects should or should not be approved.

The Grattan Institute has looked at the distribution of grants in programs run by the federal government and the governments of the three largest states, and has found that in general government-held electorates receive much more funding that opposition-held electorates. Media reports of this work suggest that Coalition and Labor governments are equally guilty of pork barrelling, but the Coalition is the master at pork barrelling: the standout programs are the Commonwealth Community Development Grants, the Commonwealth Sports Infrastructure Program, and the New South Wales Stronger Communities Fund.

The report’s authors – Kate Griffiths, Anika Stobart and Danielle Wood – summarize their findings and recommendations in a Conversation article: Pork-barrelling is unfair and wasteful. Here’s a plan to end it. There is a link to their full report at the Grattan website, and Danielle Wood has given a short account on ABC Breakfast. (7-minutes) It’s worth flipping through the full report, even if it’s to do no more than to see the rigour of their analysis and to read on Page 16 some politicians’ outrageous justifications for political discretion. Everyone does it, therefore it’s OK.

The authors’ propose, in line with most normative standards of good public administration, that ministers should define the purpose of a grants program, and approve the program’s selection criteria, leaving the allocation to the relevant government department or agency.

Also on ABC Breakfast, Industry and Science Minister Ed Husic discusses the revelations about the Modern Manufacturing grants and the Grattan findings and recommendations. He is quick to criticize the Coalition’s record, but he doesn’t go along with the recommendation for removal of ministerial discretion. (12 minutes)

His reasons for retaining ministerial discretion in grants programs are unconvincing. When we look at the reputational damage discretionary grants have done to the Coalition, we might reasonably ask why Labor wants to subject itself to the same risk. The ANU’s Ian McAllister has looked for evidence that pork barrelling is of benefit to political parties, and has found that it’s not a big vote winner. He tentatively concludes that voters take a cynical view of pork barrelling, and politicians tend to over-estimate its political benefits.

Why Malcolm Turnbull will be voting for an indigenous voice to Parliament

In an essay in The Guardian – I will be voting yes to establish an Indigenous voice to parliament – Malcolm Turnbull explains why he has come around to support a “yes” vote in a referendum for a constitutionally enshrined indigenous voice to Parliament. His own preference would have been for mechanisms to have been developed at local and national levels first, before being put to a constitutional amendment, but he acknowledges the effort and careful consideration that has gone into this project. The people involved have dealt with some of the concerns he and others had earlier expressed.

Anyone who has misgivings about the proposal would do well to read his essay, where he explains both the deliberately constrained power of the Voice and its importance. There would have to be very strong reasons for anyone to say “no” to the change. He writes:

In my view, there is enormous goodwill behind reconciliation and constitutional recognition in principle. A rejection of this proposal would be, once again, because a constitutionally conservative nation was not sufficiently persuaded of the merits of the change.