Our winter of discontent – the pandemic

Epidemiologists and other public health experts are expressing discontent on three aspects of Covid-19 – information, compliance with advice, and political leadership.

Andrew Robertson, Western Australia’s Chief Health Officer, is frustrated by the lack of Covid-19 modelling in the state health department. Early on we had the Doherty Institute modelling guiding public policy, but now public health officials seem to be relying on back-of-the envelope models.

ABC Adelaide journalist Daniel Keane quotes epidemiologist and biostatistician Adrian Esterman, who is frustrated by Covid complacency. Even on public transport, a high risk setting and where in South Australia there is a mask mandate, compliance is low. Frank Bongiorno, writing in The Conversation, asks if we care enough about Covid, and criticizes governments for taking what he sees as a utilitarian approach to Covid: if a few people are dying each day that is balanced against the benefit to others who, in the absence of mandates or hectoring about vaccination, can go about their daily business. But even on utilitarian grounds, measures such as enforced mask mandates are low-cost.

Charis Chang of SBS News quotes AMA Vice-President Chris Moy and epidemiologist Catherine Bennet who both call for more leadership from governments, state and Commonwealth: 'Complete lack of leadership': Australia condemned as COVID-19 hospitalisations set new record. Although governments are urging people to get booster shots, progress is painfully slow. At our present rate it would take two years for all adults to have received their third dose.

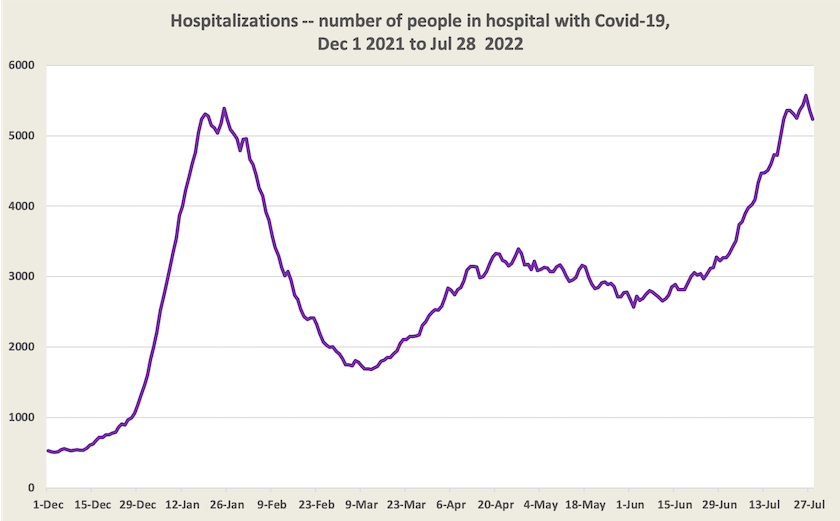

Hospitalizations (i.e. the number of people in hospital with Covid-19) have indeed reached a new high point. An optimist may say they have peaked, but such a conclusion would be premature.

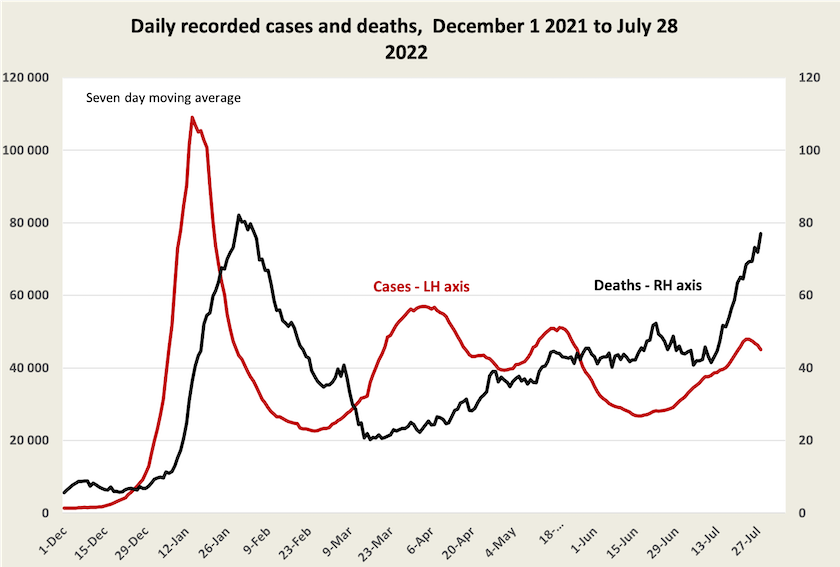

While hospitalizations provide the most reliable data, there is also data on cases and deaths.

Cases seem to have peaked, about one week ago. We know, for various reasons, that case numbers are understated, but if this understatement is consistent then cases may indeed have peaked. When we drill down into data at a state level cases seem to have peaked in all states apart from New South Wales. Even if a peak has been reached, however, we would not expect to see a turnaround in death figures until early to mid-August.

A check on the extent of understatement of cases is provided by antibody testing undertaken by the Kirby Institute. That testing, an update of their earlier work, suggests that as at mid-June, at least 46 percent of Australians had been infected with Covid-19 (a figure that’s significantly lower than is revealed in the somewhat scrappy data coming from other countries). Because in mid-June official figures showed that 30 percent of the population had been infected, these antibody tests suggest that the understatement bias is in the order of 50 percent: for every two reported cases there is an additional unreported case. Applying that factor to most recent case numbers suggests that just over half of Australians have been infected with Covid-19. (Relevant qualifications to these estimates are in the June 25 roundup, when the earlier results were noted.)

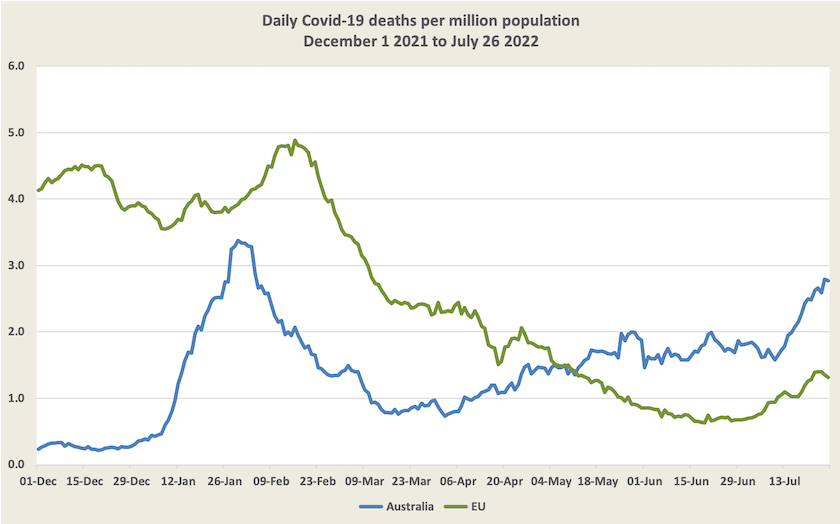

As Norman Swan explains, international comparisons are tricky, because medical practitioners can be lax about reporting causes of death, and some countries record all deaths as Covid deaths, even if there are other likely causes, while in Australia we tend to be cautious, recording as Covid deaths only those who die of Covid, rather than those who die with Covid: there is about a 20 percent difference between deaths with Covid and deaths of Covid.

Even with these qualifications, Australia’s Covid-19 death rate seems to be high in comparison with other “developed” countries, as revealed in a comparison with the EU. In interpreting this graph we should note that the Omicron wave hit Australia later than it did in Europe and there is probably a summer-winter effect.

The rate of deaths per recorded case – what epidemiologists call the “case-specific death rate” is still creeping up. In late April it was around 0.07 percent, or around 1 death in 1400 cases. It is now around 0.25 percent, or around 1 death in 400 cases, but it’s considerably higher in Victoria (1 in 300 cases), and is still low in Western Australia (1 in 1400 cases).

It is notable that case specific death rates in both Western Australia and the ACT are low. These are also the jurisdictions with vaccination rates significantly higher than in other states and territories. It would be rash to draw any conclusion about a causal relationship however. There could be many intervening variables. Also because Western Australia’s vaccination uptake was later than in other states, Western Australians may still have stronger vaccination immunity protecting them against severe disease, and as for the ACT, all those good public servants, academics and soldiers stay at home during winter writing blogs and pursuing other wholesome pastimes.