Public policy

Chalmers’ economic update

In many ways Treasurer Chalmers’ economic update – the Ministerial Statement on the Economy – follows an established pattern for an incoming government. Emphasize the mess the previous administration handed on, cite external factors making things even worse, and promise that things will pick up before the next election.

This time that standard narrative has some justification: “the fault lies with a decade of wasted opportunities, wrong priorities and wilful neglect – that Australians are all now paying for” he says.

He puts high inflation and the corresponding shortfall in real wages down to years of neglect of our economic structure: “a decade of energy policy paralysis”, “a lack of the right investment in skills and local manufacturing capability”, and “an objective to keep wages low as a deliberate design feature of the economy”.

He also lays some of the blame on Putin and Xi.

It’s mainly an economic statement rather than a fiscal statement. There is a section on the budget, but it’s mainly a re-statement of Labor’s election promises, with some adjustments for unexpected Covid-related expenditure and lower revenue in coming years, mainly because there will be little wage growth. Preparation of the budget will be aided by an Audit of Rorts and Waste, which should find some savings. But those hoping to find hints of a substantial lift in taxes will find nothing in this statement. Labor has inherited not only an economic mess, but also, it seems, the Coalition’s economically destructive “small government” philosophy.

The most notable aspect of the statement is the forecast that over this fiscal year there will be a small decrease in real wages, and only modest growth after that.

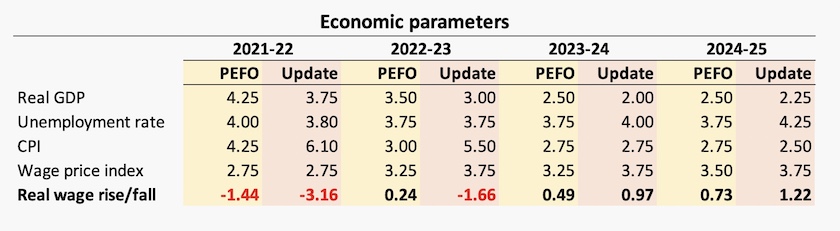

At the end of the Treasurer’s speech is a mind-boggling table, with a mixture of decimals and fractions. Without changing any of the data, I have tried to simplify it, and have added a line revealing the implicit change in real wages. I have not included the 2025-26 forecast – that’s getting into the realm of creative fiction.

Most striking are the differences between this statement and the Pre-Election Economic and Fiscal Outlook (PEFO), prepared by the same people who prepared this statement. In the short term there are big changes in expected CPI inflation, and there is a substantial reduction in GDP growth for this year and the next two years. Has the world really changed that quickly?

Cost of living – the “skyrocketing” CPI

There was a time when a 6.1 percent increase in the CPI would have been seen as somewhat on the high side, but would not have ABC journalists talking about “skyrocketing” inflation.

But perhaps their over-used adjective is correct this time, because rockets have a short flight before falling back to earth. The inflation we are experiencing is not the self-sustaining type, where wages feed into prices which feed back into wages in a continuing feedback cycle. What little movement there is in wages is well below the movement in CPI.

At the core is the classic driver of inflation: there is too much money in Australia (as in other countries) to match the economy’s productive capacity.

There are many reasons why our productive capacity is constrained.

They’ll get mrore affordable

One is the pandemic, which has had an impact on global supply chains, affecting a whole range of imported goods from cars to timber, to name two items that contribute heavily to the latest CPI. Also, the pandemic has its domestic consequences due to absences: although office workers can work from home while infectious, people who do immediately useful work have to absent themselves from workplaces.

Another is Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which has had an immediate effect on the price of energy, including gasoline, and the price of grain. Both show up strongly in our CPI: bread prices in this quarter have risen by 3.1 percent. We should spare a thought for those millions in the world where high fuel and grain prices are causing severe hardship.

Then there are our own problems with food supply, most notably caused by the heavy rainfall and flooding in our horticultural regions in New South Wales and Queensland.

Some of these pressures should ease in the coming months. That’s why it would be rash for the Reserve Bank to react too heavily to lagging and partial indicators such as the CPI: its job, within its narrow remit, is to deal with expected inflation.

But the problem that will take longer to rectify is a weakness in the economy resulting from years of neglect of structural reform, under a succession of (mainly) Coalition governments. We have not invested in the skills and education needed in our economy, we have been pitifully slow in making a transition to low-cost renewable energy, we have let our transport infrastructure decay, and we have taxation policies that encourage speculation in housing and other quick-return ventures while penalising long-term patient investment. These structural weaknesses will take time to rectify.

“Housing has become one of the most pressing policy challenges of our time”

That’s a quote from the OECD document Housing taxation in OECD countries. It states:

The concentration of demand in supply-constrained areas has pushed up house prices and deteriorated housing affordability across many OECD countries. Unprecedented house price growth has been making it harder for younger generations to become homeowners and build up housing wealth. … The functioning of housing markets also has wider social, economic and environmental implications, including for social cohesion, financial resilience, residential and intergenerational mobility and the transition to a low-carbon economy.

Nassim Khadem, writing on the ABC website, summarizes the report’s findings in relation to Australia, particularly the resource misallocation and price inflation resulting from our capital gains tax breaks: 'Unprecedented growth in house prices': OECD calls for cap on housing tax breaks benefiting the rich.

Australia stands out for bearing the highest household debt of all 34 OECD countries, and the second-highest mortgage debt. In terms of how many years a person on an average income takes to pay for a 100 square meter dwelling, Australia is one of the most expensive countries. Also, presumably reflecting our generous tax breaks for housing speculators, Australia is second (to Luxembourg) in terms of “secondary real estate wealth” (housing that is not owner-occupied), and that wealth is highly concentrated in the 20 percent of people with the highest income.

Australia gets one positive mention for its early moves to shift housing taxation from housing transactions (buying and selling) and on to house ownership, so far partly under way in the ACT and at an early consultation and planning state in New South Wales.

The OECD report draws attention to the environmental impacts of housing, and with its European bias notes the amount of energy devoted to house heating. The same applies to Australia, but more in relation to cooling, in suburbs lacking the ameliorating effect of tree cover. Writing in The Conversation Gregory Moore of the University of Melbourne points out that our Urban patchwork is losing its green, making our cities and all who live in them vulnerable. He has taken to the air for his observation, but you can get much the same impression from Google Maps. Look not only for street trees (remembering that they take time to grow), but also for open space close to houses, not including areas likely to be fenced off such as golf courses and sporting grounds cleared of trees. (The above hyperlink on Google Maps is set to a newish development in Logan, south of Brisbane.)

Closing the gap

There is progress in closing the gap between indigenous and other Australians, but it is patchy, and in some important areas the gap is widening.

The Productivity Commission has published the Annual Data Compilation Report on the National Agreement on Closing the Gap. The data monitored by the Commission covers indicators of the progress towards meeting 17 specific targets in socioeconomic outcomes, 9 of which are updated in this report. To quote from the summary:

Four are on track (healthy birthweight of babies, the enrolment of children in the preschool, youth detention rates and land mass subject to rights and interests).

Five are not on track (children commencing school developmentally on track, out-of-home care, adult imprisonment, suicide deaths, and sea country subject to rights and interests).