The pandemic and how it’s overloading our hospitals

Awareness at last

Perhaps it was the election, perhaps it was the floods, perhaps it was the war in Ukraine, but whatever it was, Australians took their eye off Covid-19, until it became too obvious to ignore. Any nurse or doctor working in a hospital could have warned us that the health care system was stressed, as could have anyone waiting for elective surgery, even before there was any specific awareness of the latest Omicron variants.

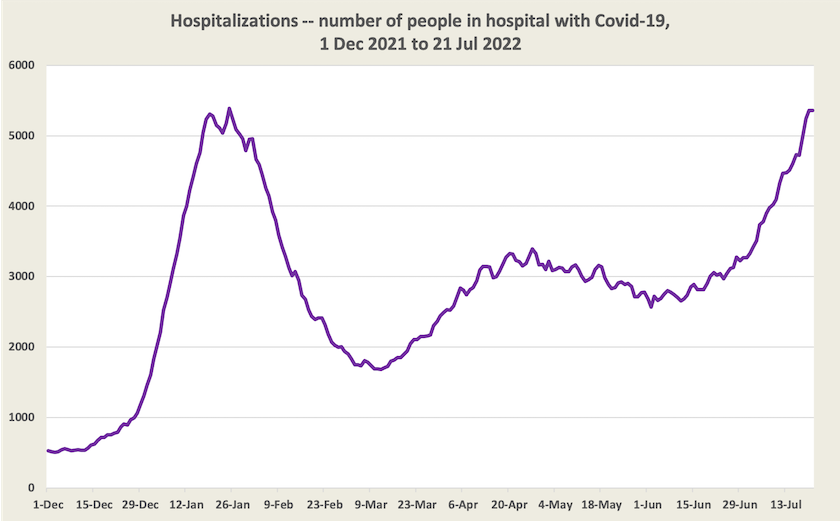

A graph on hospitalizations shows that by now, in terms of the load on health resources, this outbreak is at least as burdensome as the initial Omicron surge in January.

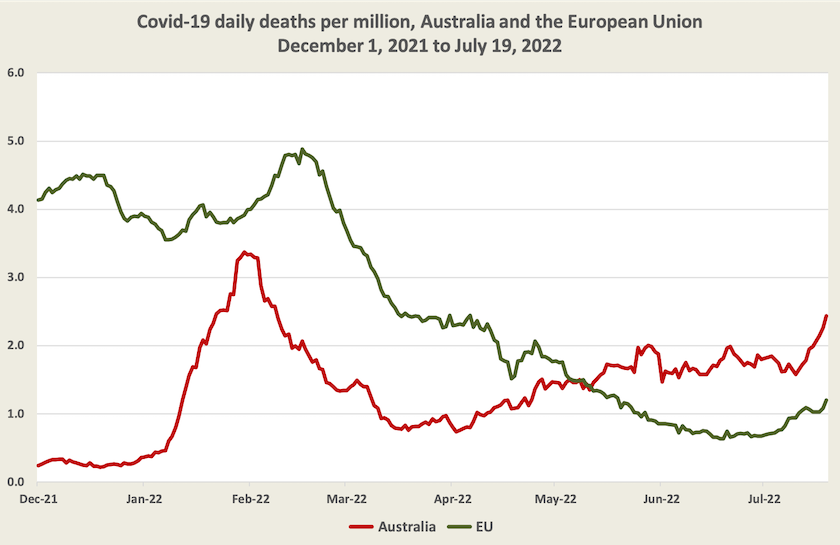

Australia is not alone in this outbreak, but in comparison with most other “developed” countries, we seem to have a high incidence of death from Covid-19.

The chart below compares our daily death numbers per million with that of the EU. Europe was hit earlier and harder than us by Omicron (and possibly by some residual Delta), but our death rate per million has been higher that in the EU for the last two months: it is now twice the European rate. Is this to do with our and their summers and winters being out of sync, or with the fact that in Australia Omicron and its variants have been spreading among a previously uninfected population? Nigel McMillan of the Menzies Health Institute is warning that Covid-19 is on track to become our leading cause of death overtaking heart disease as our #1 killer.

Somehow Covid-19 is keeping well ahead of the capacity of public health authorities to analyse its progress. That’s odd when many of us have cars that display on a screen real-time traffic information and likely trip times, based on massive computational power applied to masses of data. It seems that public health has never had the money for timely data analysis. It’s little wonder then that we all seem to have been caught off-guard by this latest outbreak.

No one knows just how many people are catching Covid-19. The media refer to figures such as 50 000 a day, but these figures relate only to cases reported to public health authorities. They exclude asymptomatic cases, false negatives on RAT tests, and cases where people just don’t bother even testing for Covid-19. And on top of Covid-19 this winter is turning out to be a bad one for other respiratory illnesses, including influenza – certainly the worst since 2017.

It’s probably been workplace absences contributing to school staffing shortages, air travel chaos and project delays, that has really brought the situation to the attention of the public and policymakers.

This wave of the virus has placed us in a situation where there is a divergence between personal collective interests. In the early waves of the virus, before there was any vaccine, fear of death or serious illness was enough to make people accept the harshest of measures, even curfews and lockdowns. Now, however, anyone in good health, with maximum vaccination, and who knows that effective anti-viral medications are available, can make the personal assessment that he or she bears little risk of severe illness or death. Even a mask mandate now looks like an unnecessarily onerous restriction to many people. So people go about life as usual, with scant regard for public health precautions, often unknowingly spreading the virus, with serious consequences for the unvaccinated, people with weakened immune systems, the frail and the very old, thereby putting a load on our health care resources and forcing aged-care homes into lockdowns.

Realistically governments cannot impose hard restrictions, but the best they can do is to try to slow the spread of the virus so that hospitals do not get overloaded, using behavioural nudges, and hoping that enough people are sufficiently civic-minded to help achieve this end.

Policy responses

A hastily-convened meeting of National Cabinet brought about a temporary resumption of Covid leave payments, but not any national mask mandate or “Jobkeeper”-type payments. For even these modest moves journalists were in haste to accuse the government of a “backflip”, as if there is some virtue in policy rigidity in the face of changing circumstances.

Governments are now urging people to get vaccinated. Nationally, we reached a high level (96 percent) of adults (16+) with two-dose vaccination, but only 68 percent of adults have received a third dose, and fourth dose vaccination is just getting underway. Since the beginning of this month there has been some pickup in third-dose vaccination, but it’s still slow: at the current rate it would take at least 18 months for our third-dose coverage to reach our second-dose coverage.

The most serious policy considerations relate to the funding and resourcing of health care, and Covid-19 is amplifying stresses already present in our health care arrangements.

Many people diagnosed with Covid-19 are eligible for antiviral medication, but some cannot secure a timely medical appointment in order to get a prescription, even though the medication should be taken as soon as possible after symptoms develop. We may be paying a deadly price for a long-standing demarcation issue, originally designed to protect GPs’ commercial interests but that is quite dysfunctional when our primary health care networks are so badly overworked.

Similarly, for those whose employment conditions include paid sick leave, many employers insist on employees producing a medical certificate to justify use of that leave, further overloading the primary health care system. There is something feudal in employment arrangements where an employer places more trust in an unknown GP or JP rather than in the businesses’ own employees. If this is what businesses and unions think is normal, it reveals a terrible trust deficit, and an assumption that workers have no intrinsic motivation to turn up to work. That’s a problem in our industrial culture, going way beyond problems in our health care arrangements.

Above all there is a resource problem. We need more nurses and medical practitioners in our hospitals, not only to cope with high demand, but also to replace those who are leaving these professions, often because of burnout. While the government is taking a cautious approach to increasing immigration, it has given priority to immigrants with health care qualifications, but in a world where every country is dealing with Covid-19, Australia is hardly in a buyers’ market for health care staff.

The longer-term solution has to lie in investment in university courses, and in structural change in our health care arrangements so that we use the resources we have more efficiently and effectively. On the ABC’s The Money program on Thursday night Jennifer Doggett, of the Centre for Health Policy Development, provides a 15-minute presentation of what meaningful and practical reform would look like. Such reform would see the provision of services more appropriate to people’s needs, and more tolerable working conditions, without excessive demands on the public purse or on our own pockets. Like other health policy specialists, Doggett is particularly mindful of the way fragmentation of responsibilities, particularly between the Commonwealth and state governments, and the multiplicity of funding sources, is holding back the performance of Australia’s health care systems.