Public policy

It’s time we talked about tax

Jim Chalmers is running true to script for a treasurer in a newly-elected government. As the standard speaking notes put it, because the outgoing mob left a terrible deficit the new government is going to be really tough in getting the nation’s public finances back in order.

For once that political message aligns with reality: they really did leave a large debt, with not much to show on the other side of the balance sheet.

In the situation confronting Australia in 2020 and 2021 any responsible government would have applied expansionary fiscal policy, but they would have tried to spend in ways with lasting benefits, rather than simply boosting corporate profits through loosely-designed programs like “Jobkeeper”. Then, putting more stress on public finances, there was a splash of pre-election discretionary spending, even though all signs were that the economy was recovering rather quickly.

Chalmers’ fiscal update to be presented to Parliament will probably confirm the figures in the Treasury’s Pre-election Economic and Fiscal Outlook: gross debt by the end of 2021-22 will turn out to be around $920 billion (conveniently rounded up to “one trillion”) and net debt will be around $630 billion, or close to 30 percent of GDP. They’re big figures, but still lower in relation to GDP than the situation in 1945 at the end of the Pacific War.

There is no fiscal relief on the horizon, and the government has committed itself to the Coalition’s income tax cuts from 2024, that will cost $16 billion in its first year, with three-quarters of the benefit to be enjoyed by people with incomes of $120 000 and higher. That’s hardly the best fiscal setting when real wages are falling and the well-off are generally in a stronger financial situation than they were when the pandemic broke out. Stephen Koukoulas presents a strong argument, with political face-savers, for the government to repeal “Morrison’s irresponsible tax cuts”, but Labor seems to be determined to stick to every one of its election promises.

The government has some modest spending commitments – a net $7 billion over four years, after dealing with some of the Coalition’s most egregious waste. In a $600 billion budget that’s closer to a rounding error than an accurate estimate.

In terms of the fiscal task this government must confront, these figures are all close to insignificant. We have a badly underfunded public sector: it was underfunded before 2020, and in the last two years the situation has worsened.

When we look around at the condition of government services we see stressed and underfunded public hospitals, schools, aged care, disability services, primary health care, universities, and technical education. These are all skilled labour-intensive services, for which there is a need for both higher pay for existing staff and more budgetary allocation to finance additional staff. In addition there is pressure on our defence budget, and there is still a great deal to be done to bring our public infrastructure up to date.

To put it simply, we aren’t collecting enough tax to fund our public services.

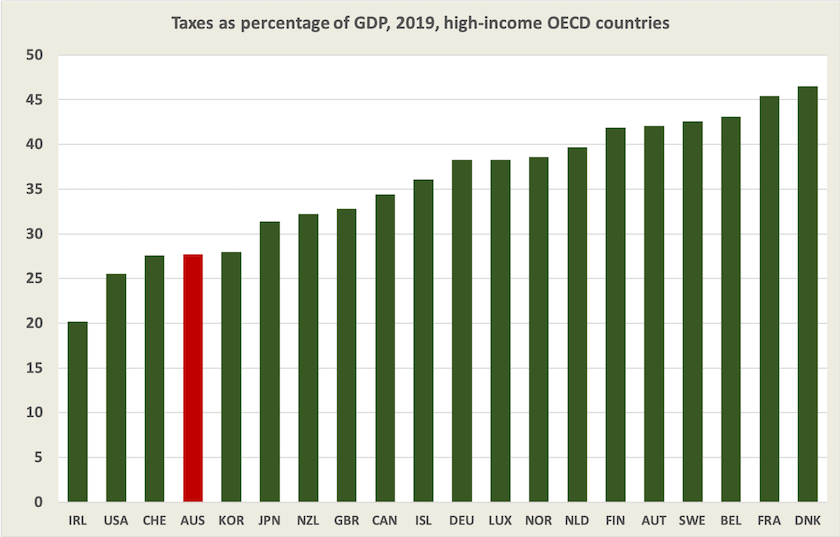

Among the world’s prosperous “developed” countries, Australia has one of the lowest tax-to-GDP ratios, as shown in the chart below, taken from the most recent data for the twenty highest-income countries in the OECD.[1] At 28 percent of GDP (roughly 22 percent Commonwealth, 6 percent state and local), we are near the bottom.

A defender of our low ranking may point out that three countries – Ireland, the USA and Switzerland – are getting by with lower taxes, but it’s worthwhile looking at their arrangements to forestall any suggestion that they offer a fair basis for comparison with Australia.

Ireland has gotten by as a tax haven for multinational companies, but as G20 countries come to agree on minimum taxes for multinationals and crack down on tax havens, that arrangement may be coming to an end. Ireland’s “leprechaun economy” is a passing phenomenon. In any event such tax competition is an option only for small countries: Ireland’s population is 5 million, while ours is 26 million.

The USA manages by running huge budget deficits – 6 percent of GDP – a situation sustainable only so long as the rest of the world is willing to finance America’s current account and government deficits. That’s one of the benefits, or curses, of a country whose domestic currency is a safe haven world currency. If the USA were to finance its public spending from a balanced budget, its taxes would be around 32 percent of GDP, significantly higher than Australia’s. Also any worker in the USA virtually has to hold private health insurance – essentially a “privatized tax” which is not counted in public finance figures.

Then there’s Switzerland, but before any readers rush off to Switzerland with their fortunes, they should be warned that Swiss workers are actually compelled to take private health insurance, that the government collects non-tax fees on bank accounts, and that some of those cute little cantons impose special levies on their residents.

Some may note that Korea has a tax-to-GDP ratio similar to ours, but it is on a trajectory of collecting more taxes.

If we were to lift our taxes perhaps to 35 percent of GDP – a figure that would put us somewhere between Canada and Germany – we would be collecting around another $150 billion a year. At first sight that appears to be beyond reach, but one thing the Albanese government has inherited from its predecessors is a country with plenty of untapped taxation capacity. Even if income tax rises are presently off the agenda, there are opportunities to tax the incomes of so-called “self-funded” retirees, to crack down on family trusts (the choice of small business), to tax inheritances, to impose a realistic resource rent tax, to tax rentier income, to collect levies in the form of tax surcharges for specific purposes, and to raise the rate and scope of the GST (Norway’s 25 percent VAT hasn’t left households struggling).

Improving our tax base should be a task for the Commonwealth. States can and do collect taxes, but many, such as motor vehicle registration, are regressive. State payroll taxes don’t do anything for employment or wages, and state governments have become dependent on gambling taxes, treating the harm of poker-machine addiction as collateral damage in satisfying their need for public revenue. The Commonwealth has more capacity than the states to tax fairly and to use taxes in ways that improve resource allocation.

1. For this comparison I have chosen the 20 countries with per-capita GDP above $US42 000 in 2020 (purchasing-power-parity) . With a per-capita GDP of $57 000 Australia occupies position #9, around the middle of this group. Some commentators use the entire 38 OECD countries as a basis for comparison, but that is to include a large number of low-income countries in the Americas (Colombia, Costa Rica, Mexico), in the Mediterranean (Italy, Greece, Turkey), and in former Soviet-zone eastern Europe (Hungary, Poland). ↩

The Reserve Bank again

Where is the Reserve Bank headed?

The minutes of the RBA Board, explaining their decision to raise the interest rate on July 5, cover the usual issues, including national and international economic developments. They also have a section on “the neutral interest rate” – the rate that is neither expansionary nor contractionary for the economy.

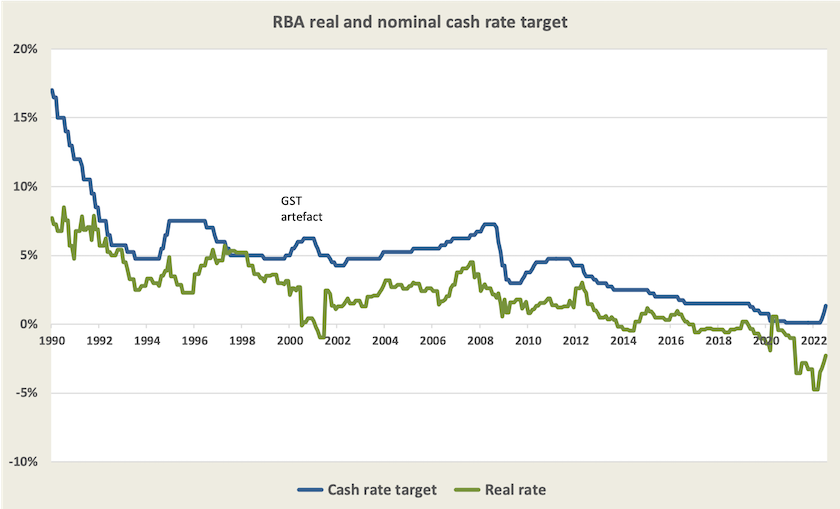

They note that the neutral rate is defined in real (i.e. after inflation) terms. Conceptually that’s straightforward: the real rate is the nominal rate minus inflation.[2] That implies some figure that’s stable over the long term. The short-term rate may fluctuate around this figure depending on whether monetary policy is expansionary or contractionary, but over the long term the rate would come back to this figure.

So what does the evidence reveal?

The graph below shows that the real rate (the green line) has been bumpy, while declining over the long term, travelling like a billycart down a rocky hill. Also it has been negative most of the time since 2017, three years before there was Covid-19. If the theory of a neutral rate has any validity, then the RBA has done a poor job in holding to that theory.

The other problem, acknowledged in the minutes, is that the nominal rate is set in accordance with expectedinflation: if the bank gets the expected rate of inflation wrong, it will set the real rate too high or too low. Anyone who looks at recent inflation forecasts will notice that expert opinion is changing almost day-by-day.

Can households bear a rise in interest rates?

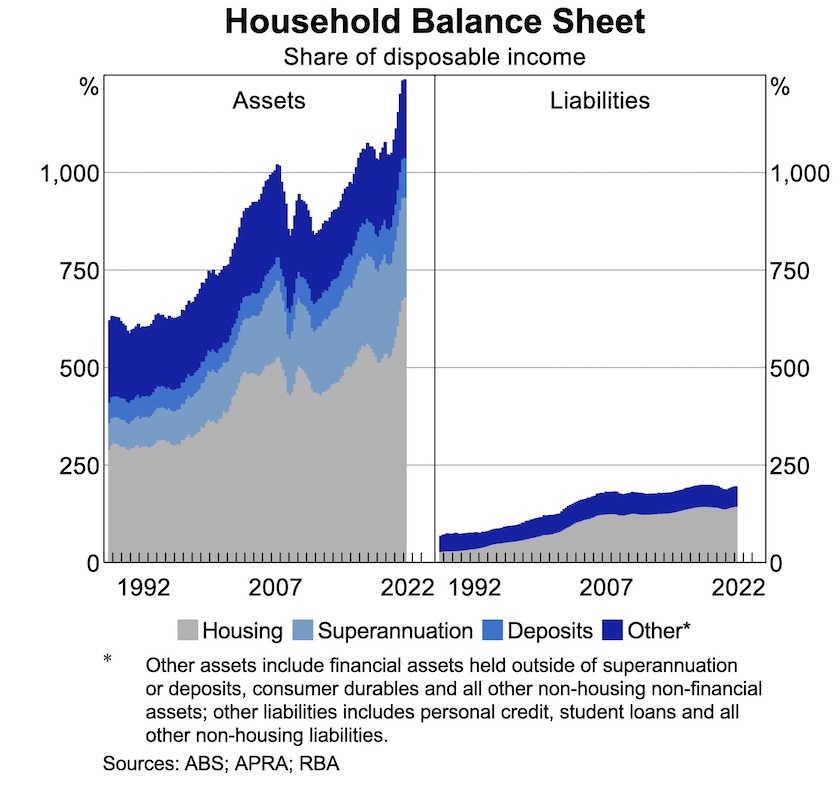

On Tuesday Reserve Bank Deputy Governor Michele Bullock delivered a well-researched address: How are households placed for interest rate increases? As has been the case with other RBA presentations on the same topic, she points out that although Australian households are carrying heavy debt, with a credit-to income ratio of around 150 percent, household balance sheets are generally strong, and that in general the highest debt is carried by the highest income households. Also, particularly since the onset of Covid-19, many households have increased their saving, including through getting ahead with additional mortgage repayments. In terms of financial stability, all should be OK, even if interest rates rise.

The media have become somewhat excited by the presentation having included a stress test, modelling the effect of a rise of 3.0 percent rise in interest rates. Is the RBA softening us up for such a rise, or is it simply presenting a model that has to be seeded with some realistic parameters? All that the bank says is that a 300 basis point rise in mortgage interest rates “is broadly informed by recent market pricing to mid-2023”.

The RBA finds, unsurprisingly, that with a rise in interest rates “the impact on individual borrowers will be varied”. Almost 30 percent of borrowers would experience a 40 percent or higher repayment burden if variable interest rates were to rise by 300 basis points. Writing on the ABC website, Michael Janda puts this figure into perspective: making it clear that the burden of higher interest rates will fall disproportionally on a few young people. Older people who own their homes outright, or who have largely paid off their mortgages from times when houses were cheaper, will be unaffected or only lightly touched by higher rates.

The RBA is somewhat in the dark when it comes to those who took low-interest fixed-rate loans in 2020 and 2021, many of which will expire and will be rolled into variable rate loans next year. Have these people accumulated savings, in expectation of rising rates, or are they highly vulnerable? Nor do we know if they are “investors” (i.e. speculators) or people living in their own homes. The RBA, however, believes that “investors” are likely to have resources to withstand a rise in rates, implying therefore that the pain is more likely to affect people paying off their own homes.

Is the RBA’s charter so narrow that it is exempt from any consideration of the equity effects of its decisions?

Another problem with the RBA’s way of looking at the world is captured in their presentation of the average household balance sheet, copied below:

That all looks healthy. Households, or at least the “average” household, have plenty of assets on the left-hand side to cover the liabilities on the right-hand side. But note that the largest component of those assets is housing, an asset whose growth in value has been due to inflation (although the RBA ignores asset price inflation), and is illiquid, as is the next biggest component of assets – superannuation. The RBA states that “the household sector as a whole has accumulated sizeable equity via higher housing prices over recent years”, but isn’t it going against the conservatism convention of accounting to count inflationary gains as an increase in an asset’s value?[3]

The RBA is not alone in seeing rising house prices as real gains, even when there is no evidence of any increase in the value of services they produce – shelter, convenience. They fall into the same way of thinking as naïve housing speculators, and people who think that because the market value of their house has risen by $X 000, they are $X 000 better off. Unfortunately, for financial stability, when X becomes negative, the same way of thinking will lead them into a depressive funk and they will stop spending.

Reserve Bank Review

Our unhappy experience with the way monetary policy has operated in Australia justifies a review of the RBA’s role – a review supported by both main political parties.

On Wednesday Treasurer Chalmers formally announced the Review of the Reserve Bank. This will review “the continued appropriateness of the inflation targeting framework”, and general issues to do with its governance, culture, and the way it trades off particular objectives.

You can hear Jim Chalmers discussing the review on ABC Breakfast, but he doesn’t give away anything that isn’t in his press release (linked above). As the very model of a modern treasurer, he holds rigorously to the line that the central bank is independent of government, and in spite of Patricia Karvelas’s best efforts, he cannot be drawn into criticizing its recent decisions.

2. To be mathematically precise, the real rate is ((1 + nominal rate)/(1 + inflation) – 1), but when the numbers are small (nominal rate – inflation) is a very close approximation. ↩

3. By the conservatism convention of accounting, assets are carried on the books at the price paid to acquire them, not some notional market price. ↩

State of the Environment Report

The media have given a fair amount of coverage to the State of the Environment Report, including the fact that the previous government, even though it received it in December last year, deliberately refused to release it.

The report’s broad finding is:

Overall, the state and trend of the environment of Australia are poor and deteriorating as a result of increasing pressures from climate change, habitat loss, invasive species, pollution and resource extraction.

Monolith Valley, Budawang National Park

That general finding is backed up with detailed assessments of 12 areas of concern.

Writing in The Conversation – This is Australia’s most important report on the environment’s deteriorating health. We present its grim findings – three senior academics from the University of Sydney provide a short summary.

Speaking at the National Press Club, Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek provides the government’s initial response to the report.

The first 15 minutes of her presentation is about the previous government’s “wilful neglect” of the environment. She refers to promises and announcements made and then forgotten, contempt for expert opinion, general poor administration, and the community’s resulting mistrust of the government’s capacity or will to address environmental problems. She refers particularly to the 2020 Independent Review of the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act – the “Samuel Review” – which recommended significant changes in governance, standard-setting and intergovernmental cooperation. This review was largely ignored by the Morrison government, but Plibersek has committed the present government to respond to it by the end of the year.

The next 15 minutes is about the government’s reaction to the State of the Environment Report. She speaks mainly about policy principles: the government has no intention to rush into any decisions that cut across so many portfolios and which necessitate consultation with state governments, local governments, corporations and community interest groups. But she does re-commit the government to its environmental election commitments, and she announces that the government will set a goal of protecting 30 percent of our land and 30 percent of our ocean by 2030.

Also, she shows she is well across environmental issues, from the effects of climate change, through the condition of the Murray-Darling Basin, to the need to protect the habitat of the Greater Glider, and many issues in between. Writing in The Conversation Laura Schuijers and Thomas Newsome of the University of Sydney summarize Plibersek’s specific commitments.

The remaining 40 minutes of her presentation is given to Q&A from the media. Unsurprisingly there are questions about Labor’s 2030 commitment to reduce emissions by 43 percent and negotiations with the Greens and others: in response she plays a straight bat, holding the party line about keeping promises taken to the election. In response to a question about possibly stopping development of coal mines she stresses that Australia is responsible for its own emissions, not those of other countries using Australian coal. (It’s hard to see this being the end of the matter, in both domestic and international forums.)

One of the more significant findings in the State of the Environment Report was that out of 450 gigalitres of water that was to be returned to the environment by 2024 under the Murray-Darling Basin Plan, only 2 gigalitres has so far been delivered. In response to a question by the ABC’s Melissa Clarke, Plibersek admitted that she was shocked by the finding, and that it would be “next to impossible” to achieve this outcome by 2024. The ABC’s Kath Sullivan has an article on this particularly important finding and on the government’s response: Water Minister Tanya Plibersek 'gobsmacked' by how badly Australia has been doing on Murray-Darling Basin Plan target. (The Commonwealth and all four MDB state governments share some responsibility for this disgraceful outcome, but the National Party, which holds a mere 12 seats in the 93-member New South Wales Legislative Assembly, bears a large part of this responsibility. Those 12 members play the part of our own Joe Minchin.)

In many journalists’ questions there is the implicit, and sometimes explicit, assumption that there is some necessary trade-off between “jobs” and “the environment”. In anticipation of this view she stresses that “good environmental law is also good economic reform”, and provides specific examples where there is no such trade-off.

The idea of a trade-off is flawed economic thinking – indeed it’s a fundamental category error – but it’s so deeply ingrained, by both the “right” and the “left”, that breaking this assumption will be an ongoing policy challenge for the government.

Legislated emissions targets – shadows of 2008

The events of 2008, when the Greens voted in the Senate with the Abbott government to defeat the Rudd government’s carbon pollution reduction scheme, have left a bitter taste with Labor. (For those whose memories are hazy, Mark Butler wrote an account of these political developments in The Guardian in 2017: How Australia bungled climate policy to create a decade of disappointment.)

Now, as Yogi Berra would say, it’s déjà vu all over again, with the Greens, now in an even stronger position in the Senate, dropping hints that they may align with the Dutton opposition to defeat Labor’s target of a 43 percent emissions reduction by 2030.

Maybe the Greens are only playing an opening gambit, and maybe Labor and the Greens would accept 43 percent to be defined as a floor rather than as a target, and even the qualifier of “at least” 43 percent. Or, maybe, the Greens have a hard-line political model akin to that of the communists of old, who would consider no compromise, rather than the model adopted by most left and progressive movements who work to lock in small gains, before moving to further progress.

Two articles in The Conversation suggest ways around a possible Green-Labor impasse. Adam Simpson of the University of South Australia suggests that Labor, the Greens, and other parties pushing for more ambitious progress, develop a strong 2035 target that would subsume the 2030 target: There’s a smart way to push Labor harder on emissions cuts – without reigniting the climate wars.

Rebecca Pearse of the ANU sees a possible meeting of minds if our carbon reduction policies can be thoroughly integrated with our industry policy: 3 lessons from Australia’s ‘climate wars’ and how we can finally achieve better climate policy.

Our green industrial future

Probably made in China

There are around 60 million solar panels in Australia – about six per household on average. Only around one percent of these are made in Australia. Most are made in China.

Australia had an early lead in solar technology, particularly at the School of Photovoltaic and Renewable Energy Engineering at the University of New South Wales where Zhengrong Shi was heavily involved in those developments. He went on to found Suntech Power in China, for a time the world’s largest solar module manufacturer.

If we are to realize our opportunities to develop along the green energy supply chains, how far along that chain should we go? Should we resurrect our solar panel industry?

On last weekend’s Saturday Extra Geraldine Doogue discussed this question with Tennant Reed of the Australian Industry Group and Gavin Lockyer of Arafura Resources, a company mining and refining rare earth minerals for magnets used in wind turbines, servo motors, traction motors and other applications key to emerging low-emission technologies, including electric vehicles.

Solar panel manufacturing has become a highly competitive industry, with thin margins. In line with the economic theory of comparative advantage, we may do better by investing in other parts of the supply chain, where there are plenty of opportunities not only for manufacturing, but also for helping other countries in our region make their own energy transitions.

Some green manufacturing can be developed quickly. If we weren’t too worried about the competitive environment we could probably be into large-scale panel manufacture within a couple of years, but other industries take a long time and a great amount of patient capital before they can provide a return to investors. Arafura Resources, for example, has been around for more than 20 years, and is only now moving into further processing.

The discussion only touched on questions of finance, but in the background is the policy environment in Australia, developed as a result of a long-standing close relationship between the finance sector and Coalition governments. Our tax and related policies favour housing speculation over value-creating investment, and we have a capital gains tax regime that actually penalises long-term patient investment while encouraging fast-turnover speculation. If we are to enjoy a green industrial future, we have to get serious about tax reform.