Covid-19

These new sub-variants really are serious

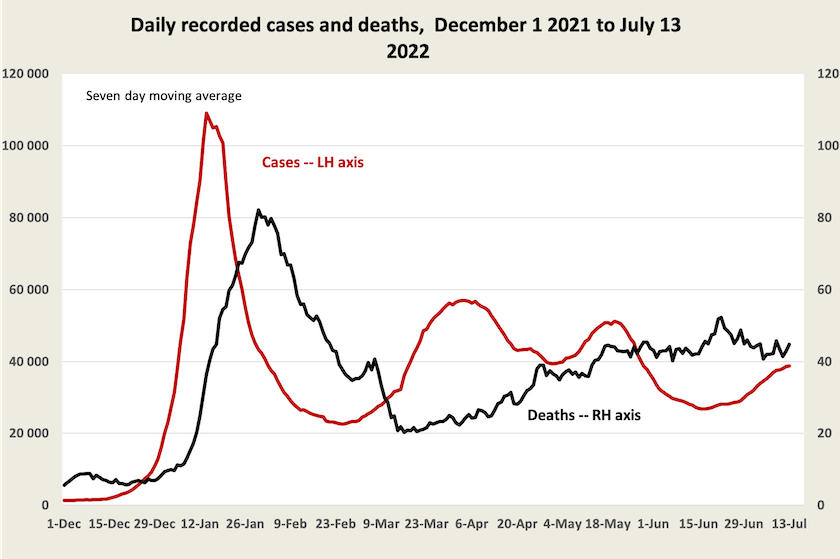

Over the last few months I have been regularly presenting the following graph of cases and deaths.

Anyone looking at this graph would be wondering what all the fuss is about: this current wave seems to be much milder than previous waves.

But why are deaths so stubbornly high?

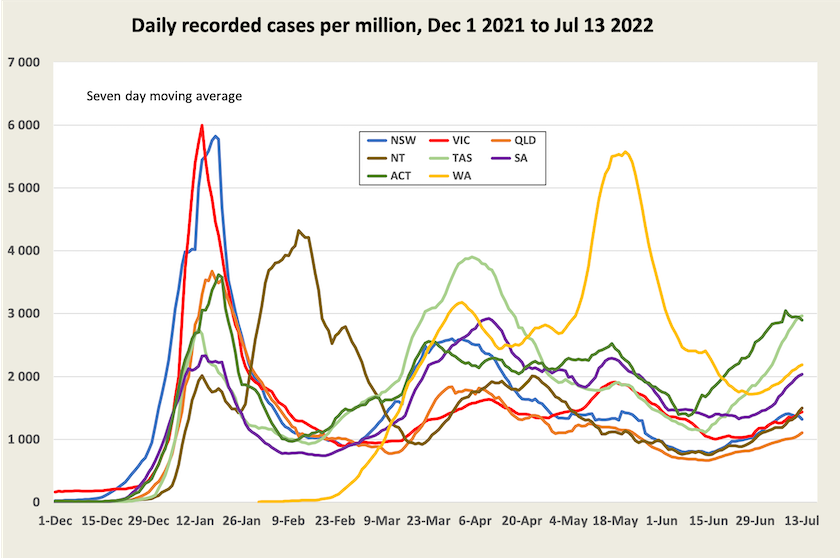

Perhaps there is something wrong with official data, based on reported cases. A look at the daily case rate by state is revealing.

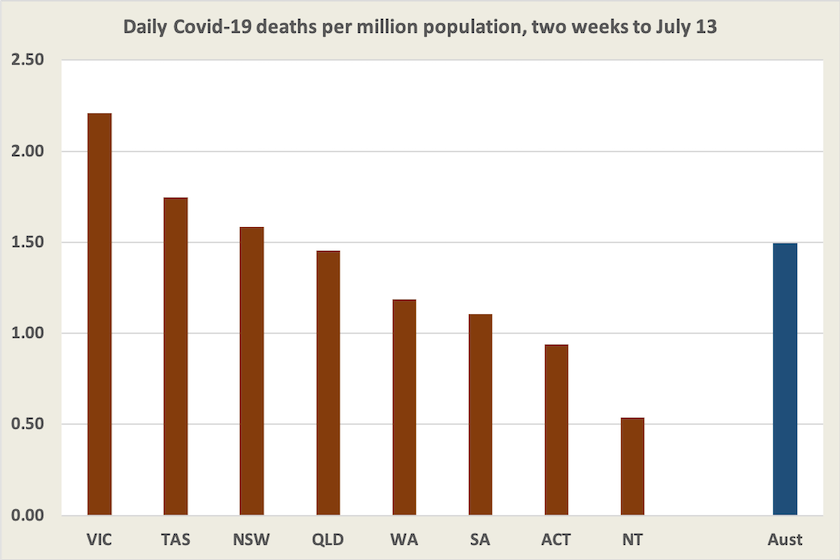

Note that the jurisdictions with the highest case rates are Tasmania and the ACT. Is this something to do with winter, perhaps? But the following chart puts paid to that idea. Based on the reported case rates we would expect Tasmania and the ACT to have the highest death rates, but the ACT actually has a low daily death rate.

Writing on the ABC website – Tasmania tops the list for new COVID-19 cases per capita – but is that really what's going on? – Alexandra Alvaro offers a convincing explanation. Tasmanians are diligent in reporting Covid-19 infections. She summarises the explanation given by epidemiologist Catherine Bennett: “Tasmanians are better at reporting their illness to the state government, and better at testing, in part due to Tasmanians having a late introduction to widespread community transmission”.

A similar explanation probably holds for the ACT where it is unthinkable for a public servant or soldier, active or retired, not to obey a direction to report cases.

In short, national and state case numbers are worse than useless. We know they have always been understated, but if that understatement bias was more or less constant they at least revealed trends, but because that degree of understatement seems to have worsened, they have masked the seriousness of the current wave.

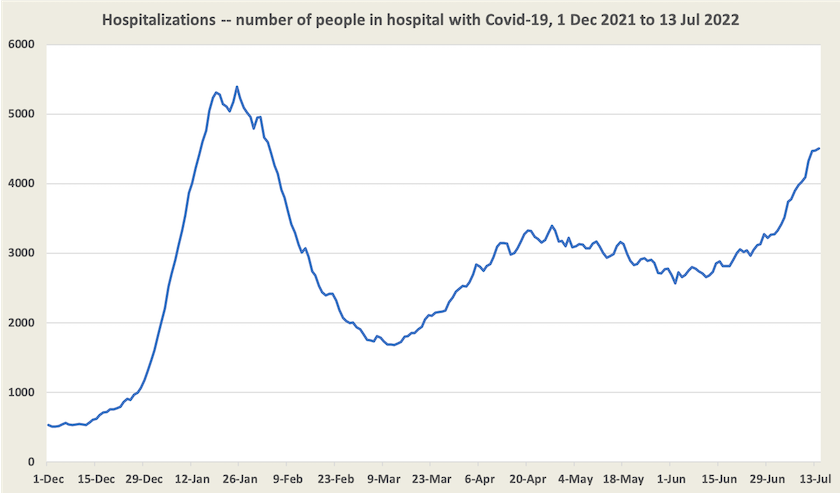

Hospitalizations give a better idea about what’s going on.

Hospitalization still isn’t the best dataset for analysis. It’s a measure of the number of people in hospital with Covid-19, not the number of people being admitted to hospital each day with Covid-19. (It’s a stock variable rather than a flow variable.) And as Juliette O’Brien points out, there are inconsistencies between different states’ measures.[1]

But hospitalization data does give us an indication of the load on the health system, and the data suggests that this surge could be becoming as serious as the first Omicron surge in December last year. Already our national daily death rate, at 1.5 per million, is significantly higher than in most other “developed” countries: the EU rate is around 1.0 per million.

Martyn Goddard has an article on his Policy Post urging governments to “do their bloody job”. He is frustrated that governments, state and federal, are reluctant to re-introduce mask mandates, and he notes that although we achieved high levels of second-dose vaccination, third-dose vaccination has stalled (while fourth-dose vaccination is only starting).

It’s clear from Health Minister Butler’s press releases that the Commonwealth is prioritizing vaccination, particularly fourth-dose vaccination, access to antiviral medications, and provision of personal protective equipment to health and aged care facilities. But that’s the limit of its response because it sees itself as bound by two political constraints: one to do with “mandates”, the other to do with self-imposed fiscal constraints.

On mask mandates, the government is politically fearful, even of urging state governments to re-institute them. Goddard points out that masks could save 2000 lives a year, and as anyone who goes shopping realizes, few people are wearing them. There is a stridently vocal far right anti-vax-anti-mask-mandate fringe, ready to raise a ruckus. And while governments may be relaxed about ignoring far-right fringe groups, in Victoria the state Liberal opposition is raising its own scare campaign, in an emotionally worded party statement: Chaos and confusion over Covid rules.

The chaos and confusion is in the statement, for it conveys the misleading impression that mask mandates and lockdowns are similar policy responses. Having seen a state Liberal opposition behave so irresponsibly, Federal Minister Butler is understandably cautious about what the federal Dutton opposition may do; the national interest rarely stands in the way of the federal Liberal Party’s political tactics.

Stephen Duckett and Sarah Duckett, writing in The Conversation, explain that we still have to deal with the Morrison government’s having weakened the social licence of governments to regulate for public health: We lost the plot on COVID messaging – now governments will have to be bold to get us back on track.

The other constraint, largely of the government’s own making, relates to its concern to contain health spending, evident in its defensive response to its decision to discontinue providing free RAT tests to certain groups, and to refuse to continue funding leave for those who have to take time off work because of Covid-19 isolation restrictions and who do not have other leave provisions. In an interview on ABC Breakfast Aged Care Minister Anika Wells explains the government’s fiscal constraints, and the difficult budgetary situation it has inherited.

The government is ducking the clear signs that health care is severely underfunded. Even without Covid, there are reasons, to do with demographics and the intrinsic labour-intensity of health care, why public funding for health care has to increase, and that increase has to be at a rate higher than the growth in GDP. That comes back to the need to raise taxes, particularly to collect taxes off highly privileged so-called self-funded retirees and small businesses avoiding tax through family trusts, and to rescind the planned personal tax cuts for people enjoying very high incomes.

1. For comprehensive data on recorded cases, deaths, hospitalizations and more, see the website maintained by Juliette O’Brien and her colleagues: Covid-19 in Australia. Data on vaccination is on the ABC’s vaccine tracker, maintained by Inga Ting and her colleagues. The Guardian’s data tracker has further select data, including reported infection rates in regions within states. ↩

Attitudes to Covid-19 – mask mandates would be OK with most people

The latest Essential Poll has a set of questions on Covid-19.

More than two-thirds of us (68 percent) say “I haven’t had Covid (or I don’t think I’ve had it). That pretty-well lines up with the proportion of people who have reported Covid-19 to public health authorities – 33 percent, assuming a negligible number of re-infections so far. (Both personal perceptions and official figures can be subject to severe understatement however – see the previous article.) Of those who know they have had Covid, most report it to be like a “bad cold”.

There is a question on the number of Covid deaths a year we would find acceptable. For what it’s worth, 42 percent answer “less than 100”, and 31 percent “between 100 and 1000”. The actual current rate is about 42 deaths a day or 15 000 a year. In view of the poor quality of coverage the mainstream press is giving to Covid numbers, this result is hardly surprising.

In fact we are already experiencing around 100 Covid deaths a week in aged care alone.

The figures make little absolute sense: they’re about as useful as surveying people on their estimate of the weight of the Moon, but they can reveal some trends and different views among different groups. For example when a similar question was asked 11 months ago we were much less accepting of Covid deaths; we seem to be becoming more resigned to Covid deaths, even if we are still severely underestimating. Women are less accepting of Covid deaths than men, older people less accepting than younger people, and Coalition voters significantly more accepting than voters for other parties.

Most of us (65 percent) realize that “hospitals in Australia are having to deal with too many Covid-19 patients and are unable to address other illnesses”, and 60 percent of us believe that “mask wearing should be re-introduced in some settings to stop the spread of Covid-19”. For these two statements older people are significantly stronger in agreement than younger people. In a slightly contradictory view, a small majority (55 percent) believe “we really need to get on with life and treat Covid like another form of flu”.

These findings suggest that people are ready to accept mask mandates, but governments are reluctant to re-introduce them.