Public policy

Interest rates

A houseboat is perhaps the most inelegant of all pleasure craft. It is essentially a large rectangular barge, with one or two big motors at the back to push its bulk through the water. A houseboat is fairly easy to drive, but steering one takes a little practice. The steering wheel (pretentiously called a “tiller”) works effectively, but with a lag. The novice driver, when changing direction or noting a drift towards an obstacle, starts cautiously, but when nothing seems to happen he or she turns the tiller a bit more, and then more. The result is almost always an overshoot, well in excess of what’s required. In response the driver overcorrects, and the boat traces out a sinusoidal path, until in time the driver learns how to keep the boat on a stable path. (At that point someone else in the group takes over, and has to learn all over again.)

Engineers and system analysts would recognize this as an example of a system with a strong response but a long time lag. Such systems, intrinsically prone to instability, are hard to keep in equilibrium. The mathematics of such systems are reasonably advanced – well beyond what is taught in undergraduate economics courses, but most mortals can learn how to steer a houseboat, keep a plane in straight and level flight, and to keep just enough wood on a campfire to give a steady heat. The trick is generally to make small adjustments and to be patient.

So it is with monetary policy. The Reserve Bank has one big steering wheel – the overnight cash rate. It’s a powerful mechanism, but the lags are significant. When the Reserve Bank reduces interest rates the finance sector responds quickly by making money easier to come by, but the real economy is much slower to react. Investment projects take months or even years to get started, and even consumer spending takes time to ramp up. Conversely when interest rates tighten the economy takes time to slow down: there are half-completed projects, households have goods and services on order, and so on. Think again of that apparently unresponsive houseboat as the impatient driver keeps turning the wheel.

That means there is always a risk of over-correction when there is heavy reliance on monetary policy as a means of stabilizing the economy. A question on the minds of many economists is whether, in recent years, central bankers, including our Reserve Bank, have actually de-stabilized their economies, first by holding interest rates too low and for too long during the pandemic, and now, perhaps, by being too hasty to raise rates.

An article by a group of ABC business journalists – Can we avoid a recession – addresses this question. Their consensus, and that of economists they quote, is that with the benefit of hindsight we can conclude that the RBA should have moved earlier to raise rates, but in view of the huge uncertainty around Covid-19 the RBA probably made a defensible decision. Less easily forgiven is the bank’s earlier promise not to raise rates until 2024. The ABC’s Nassim Khadem points out that many people are carrying high mortgage debt because they believed that the RBA had promised not to raise rates. The Reserve Bank has asserted that it never made a categorical promise, but it would take a Jesuit with a PhD in semantics to convince lesser mortals that what the bank said wasn’t a “promise”.

As the cliché goes, time will tell, but arguments about when and by how much the RBA should shift rates duck much broader questions about the whole concept of “inflation” and whether central banks, with their single effective but lagging steering wheel, can stabilize economies.

What does it mean when policymakers say central banks should keep inflation in check? Daniel Tarullo, former member of the US Federal Reserve Board, in 2017 wrote in a Brookings paper – Monetary policy without a working theory of inflation – that economists really don’t know much about inflation. It’s easy enough to teach to an Economics 1 class, from which students come away with basic ideas about cost-push and demand-pull inflation, and the workings of central banks, but the reality is much more complex, practically and conceptually. Is a once-off rise in lettuce prices because of floods “inflation”? A deliberate restoration of excise on gasoline? Is the CPI a robust indicator of “inflation” when all it does is to measure household prices? Are some price rises more damaging than others? Do not standard measures of inflation (Laspeyres’ method) overstate people’s costs because of substitution?

Economist George Stiglitz, now in Australia on a visit sponsored by the Australia Institute (with some day-long seminars in Sydney, Hobart, Canberra and Melbourne) has made a short (8 minute) appearance on the ABC’s 730 program in which he expresses his fear that the world’s central banks, including Australia’s, driven by an obsession with inflation, will plunge the world into an unnecessary and costly recession. He asks what’s so terrible about inflation that it should be responded to with measures that cause the misery of unemployment, and where did that 2 to 3 percent target come from?

Writing in The Saturday Paper Michael Seccombe questions the ability of the RBA to perform its task. The board members are intelligent people, dedicated to the job, but do they have the competencies to manage monetary policy? He quotes Saul Eslake’s quip “it’s almost like if you know something about monetary policy, you’re disqualified from membership”. (This is in the context of a number of prominent economists having called for a review of the RBA, covered in the Roundup of June 4.) An even more basic question is addressed by David James writing in Eureka Street: Rising interest rates point to a larger problem. The task of monetary policy is to ensure that there is enough, but not too much, money, in the economy, to keep it stable. But because our financial sector was largely deregulated many years ago, the banks and other financial institutions play a much greater role in creating money than the RBA. Alan Kohler made the same point in his short (2-minute) daily finance report on Tuesday.

The RBA’s statement on Tuesday, justifying its decision to lift interest rates by 50 basis points, gives the impression that it is determined to use interest rates to combat inflation, whatever its source – supply disrupted by floods and war or demand excessively stimulated by Covid-19 assistance – and however it is measured. They say they will be guided by the June quarter CPI, due to be released on Wednesday July 27, just in time for their meeting on Tuesday August 2. Will the RBA be patient enough to keep its hands off the tiller until we all have a better idea of where the economy is heading?

Where is the Australian economy heading?

Peter Martin’s regular survey of leading economists’ predictions is published in The Conversation: How the Conversation’s panel sees the year ahead.

On some indicators – inflation, the unemployment rate, wages growth – there isn’t much dispersion around the economists’ mean estimates. Inflation will ease somewhat by next year, but not down to the RBA’s 2-3 percent band, and the unemployment rate will rise a little.

They generally expect nominal wage growth to be less than inflation, meaning that real wages will fall – quite substantially by some economists’ estimates. Even so, almost all of them expect strong growth in household spending, implying a worsening in household debt. (But will the “wealth effect” associated with a declining value of housing and shares cause people (irrationally) to feel less prosperous and restrain their spending?)

On expectations of RBA interest rates, and on the probability of a recession, there is a great deal of dispersion in their expectations. Warren Hogan believes there is a fifty percent chance that we will be in recession by this time next year, while Peter Tulip of the Centre for Independent Studies, a right-wing think tank that usually has little to say for Labor’s economic management, sees only a one percent chance of a recession in the next two years.

If we can draw any conclusion from this survey it is that economists tend to anchor their estimates around government official forecasts. Where such forecasts are not published they tend to be less constrained.

Climate change – industry and security policies

Industry policy

There are three policy aspects of our path to net zero CO2 emissions. One is about dealing with the effects of climate change, an issue kept alive by floods and fires. Another is about our obligation to meet 2030 and 2050 targets, which has been at the forefront of the election campaign. And the third is about the industrial transformation we can and should undertake if we are to meet those obligations and to take full advantage of the opportunities presented by a world with high demand for energy and energy-intensive products but which is de-carbonizing.

Tony Wood, Alison Reeve, and Esther Suckling of the Grattan Institution address that third question in detail in their work: The next industrial revolution: transforming Australia to flourish in a net-zero world.

They present a disciplined and coherent argument for a strong industry policy. The government cannot sit back and hope this transition happens, because there are market failures, particularly in the development of new technologies, and firms in the private sector need a buffer to allow them to undertake high-risk investments. Above all, there is urgency, and governments can do much to speed up the process.

They go through the processes in industrial transformation, sector by sector, industry by industry. For some industries, particularly coal mining, that transformation is about an orderly departure. For some others, such as steel-making and cement, it’s about a transformation to low-emission technologies. The exciting part is in essentially new industries, such as low-emission extraction and transformation of minerals needed by a zero-carbon world – including even traditional mainstays such as copper.

In recognition of the spatial significance of this transformation they address the likely regional consequences of these developments. Much of the new activity will take place in regions other than our present industrial centres, but the thermal and metallurgical coal regions in central Queensland and the Hunter will need special attention. Suckling and Reeve have an article in The Conversation suggesting how regional-specific policies, drawn from successful policies pursued in Victoria’s Latrobe Valley, can ease this transformation: Regional towns are at risk of being wiped out by the move to net-zero. Here’s their best chance for survival.

National security

The previous government tended to see national security only through a narrow lens, and ignored the national security implications of climate change. Writing in The Conversation – Australia’s finally acknowledged climate change is a national security threat. Here are 5 mistakes to avoid, Robert Glasser of ANU urges us to consider the security aspects of climate change – food security, refugees made homeless following sea-level rises, regions becoming uninhabitable and so on.

Living with the National Electricity Market

Energy Consumers Australia, a body representing both household and small-business energy users, has released its latest Energy consumer sentiment surveys. Unsurprisingly the surveys reveal that most Australians – 87 percent – are concerned that energy will become unaffordable over the next three years, and 90 percent fear that the energy system will become less resilient. Nevertheless, only 7 percent of households surveyed believe there is no need to make a transition to 100 percent renewable energy.

These sentiment surveys are regular. From now on ECA will be developing more longitudinal behavioural surveys – asking consumers what they have done or intend to do in energy use. The October 2021 survey shows we have a long way to go in using energy more smartly: for example only 35 percent of properties have wall insulation. We’re still attached to gas cooktops and although we like the idea of smart appliances (for example appliances that can draw on electricity when it is most plentiful) they have made little inroad to our houses. Uptake of electric vehicles is still at an early stage: 6 percent of households have one or intend to buy one in the next 12 months, and a further 8 percent are considering electric vehicles in the future.

The pandemic: “living with Covid” was never a sensible idea

Perhaps it’s because Australia has accumulated 10 000 deaths from Covid-19 that there is now a resurgence in public awareness of the pandemic. There is some magic in numbers with lots of zeros.

In fact Covid-19 infections in Australia have been rising since mid-June, and deaths from Covid-19, as a percentage of the population, have been running at about twice the rate that they have been in other “developed” countries, but the media has been slow to alert us to the seriousness. The speed with which a fourth dose of vaccination has been approved shows that policymakers, however, are aware of the situation.

Although the Covid-19 virus is unaware of the conventions of the Gregorian calendar, Covid-19 outbreaks and deaths in Australia fit reasonably neatly into big blocks. Of those 10 000 deaths, only 2 000 occurred between March 1, 2020 – the date of Australia’s first death from Covid-19 – and December 31, 2021. The other 8 000 have occurred this year. In that first period, before vaccines were developed and distributed, public health authorities were dealing with a deadly disease, to be combatted with policies of testing, tracing, isolation, and general measures to reduce mobility and mixing. In the current period we are dealing with a much more contagious but less deadly disease – less deadly in part because of vaccination, in part because prior infection has given some level of immunity, and in part because the Omicron variant may be less deadly than original variants.

A description of how Covid-19 has passed through Australia is given in the report Australia’s Health 2022produced by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. It’s a regular annual document, but its release coincides with our increased awareness of our Covid-19 situation.

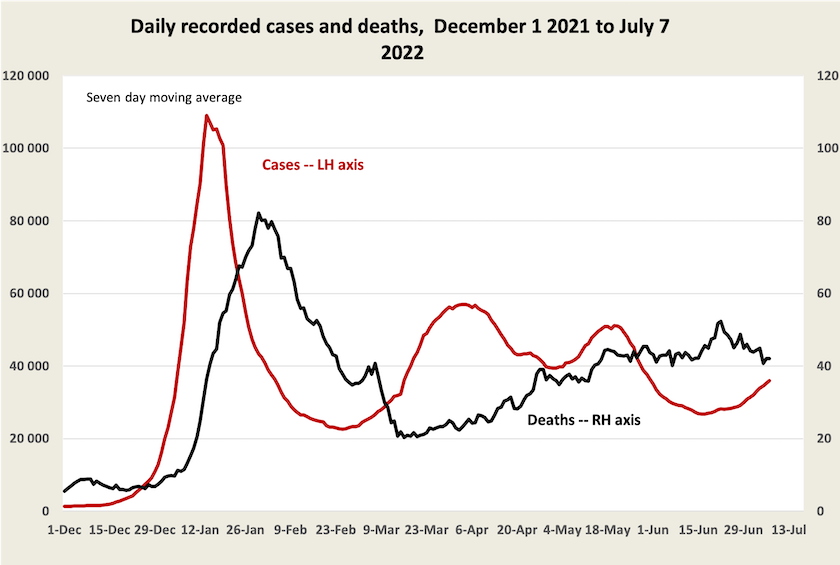

Chapter 2 of that report: “How has Covid-19 affected our health?”, provides a short and data-rich summary of how Covid-19 has affected our lives. Much of the story of Covid-19, and the policy response to the pandemic, is summarized in a graphic in that report, reproduced below.

The only qualification applying to that chart is that it takes us up to the end of April, by which stage the case fatality rate had fallen to 0.1 percent, or 1 in 1000. It has since risen to around 0.2 percent, or 1 in 500. Maybe that’s because the latest variants of Omicron are more deadly, maybe it’s because the effectiveness of vaccines and previous exposure is wearing off, maybe it’s because people in high-risk groups have let their guard down. Importantly that death rate is still very low compared with the rates prevailing in 2020 and 2021, but because there are so many more cases, the number of deaths, and therefore the stress on the health care system, has been rising. Also, as anyone who has tried to catch a plane, roster staff, or find care for children knows, Covid-19 is having a terrible effect in terms of absences from work. And there are still the largely unknown effects of “long Covid”.

Stephen Duckett, writing in The Conversation, has a summary of the AIHW findings on Covid-19, along with a description of how policymakers have been responding to it. He dismisses the idea, promulgated by the previous government and by some so-called business people, that we are now comfortably “living with Covid”. It is still a dangerous and costly menace, and we need to develop appropriate policy responses.

Those policy responses are likely to be about vaccination, social distancing, masking and possibly some restrictions on large indoor gatherings. There is no point in movement restrictions however: they apply to a different situation. (In case anyone thinks the restrictions we may have to introduce to be burdensome, a pair of US economists have suggested that everyone be required to carry liability insurance for spreading contagious disease, with penalty premiums for the unvaccinated.)

Also, there should be particular attention to those who are most vulnerable if they catch Covid-19 – the old and those with poor immune systems. Of the 10 000 deaths that have occurred so far, only 700 have been among people aged 59 or younger, while about 6 300 have been among people aged 80 or over. Another way of considering this data is that if you were over 80 in 2020 and 2021, you had a 0.5 percent probability of dying from Covid-19, but you had a 16 per cent probability of dying from all causes.[1] Such a calculation may appear to be somewhat callously utilitarian in that it implicitly dismisses the seriousness of Covid-19, but it’s at least a way policymakers consider trade-offs in health policy. That doesn’t mean the old can be neglected: Duckett is among many who are critical of the neglect of people living in aged-care homes, pointing out that many of those deaths were preventable. “Thousands of years of life have been lost prematurely because of Covid”, he writes. Also, Covid deaths have been occurring disproportionately in poorer communities.

In the last few days there have been several contributions from public health experts explaining the BA.4 and BA.5 variants of Omicron. Adrian Esterman of the University of South Australia, writing in The Conversation, explains how over the two and a half years the virus has been circulating it has become about six times more contagious. On ABC Breakfast Sharon Lewin of the Doherty Institute explains the public health issues around vaccination, pointing out that the majority of deaths in Victoria (where deaths have been particularly high) have been among people who have not had a third vaccine dose. (7 minutes). On the same program Coronacasthost Tegan Taylor explains how mRNA vaccines work and why it is possible to update vaccines and have them approved within 8 to 10 weeks. Possibly there will be an Omicron-specific vaccine available in time for the northern hemisphere winter. (7 minutes)

1. These are back-of-the-envelope figures for illustration, without any claim to precision. There are reasonably robust figures on Covid-19 deaths by age kept by the Commonwealth Department of Health: Coronavirus (COVID-19) case numbers and statistics. Background deaths are from AIHW National Mortality Database: in 2020, out of a population of 1 080 000 Australians aged 80 or over, 87 878 died. That’s an 8.1 percent annual death rate, or 16 percent over two years. Crude, but good enough for government work. ↩