Politics

Reminder to Albanese: Australia is a parliamentary democracy

So far the government is handling the provision of parliamentary advisers for crossbenchers as an exercise in bargaining over resource allocation, but it should be raising questions about the changing nature of our parliamentary democracy.

On ABC Breakfast Patricia Karvelas asked Finance Minister Katy Gallagher why the prime minister “has put the crossbench offside” by cutting their staff allocations. Gallagher provided a plausible defence for the decision. She explained that even with one parliamentary adviser, competent in policy issues (distinct from lower-paid and less-qualified electorate staff) the corssbenchers are privileged in relation to members of parliament from big political parties; she said that there would be extra resources for the Parliamentary Library; and she reminded us that parliamentary committees on which many crossbenchers will sit are well-resourced. She also pointed out that the previous government’s allocation of parliamentary advisers was a once-off political deal crafted in 2019. She did not mention, however, that the Rudd-Gillard government had allowed crossbenchers two parliamentary staff. (13 minutes)

Writing in The Conversation – Cutting crossbench MPs’ staffing would be a setback for democracy – Tim Payne of the University of Sydney, who previously worked as an adviser to independent Peter Andren, describes the workload and responsibilities that fall to a committed independent member of parliament. “Every independent MP needs to form their own position on every piece of legislation, amendment, division, motion and matter of public importance, and every report tabled in parliament” he writes.

Crispin Hull comments on the possible political costs of the cutback – Labor’s Senate danger – reminding Labor that both the Whitlam and Rudd governments were forced to untimely early elections by a hostile Senate. “The slap in the face to the half dozen ‘teal’ independents is inexplicable. They took seats from the Liberals that Labor could never hope to win. Labor needs them to help keep the Liberals out”.

The issue will probably be resolved in a way similar to the bargaining process in a tourist bazaar, probably settling on an allocation of two. But such a process would avoid dealing with fundamental questions about the nature of our democracy.

For a start, why is the decision one for the prime minister, and not for Parliament? Executive government acts only with the authority of Parliament.

And why should half the members of parliament, elected by two-thirds of the electorate, be restricted to the resources of the Parliamentary Library (unless they are independent in which case they get a number between one and four policy advisers) while the winning party that commanded one-third of the vote, has the entire resources of the public service to advise it?

The problem of parliamentary staff has not arisen because of some anomalous outcome of the 2022 election: our parliament is evolving as our political interests no longer fit with the old two-party system, based on social class identities and interests. Maybe we are heading for a multi-party system, as in mainland European democracies, or maybe we will work out something for ourselves with a large number of independents, many with specific regional interests. After all, Australia has a sound tradition in political innovation. But whatever we do, we cannot go on trying to force-fit the UK “Westminster” model into our parliamentary arrangements.

The promise to expand the Parliamentary Library is a help, but it is primarily a research institution, highly valued for its independence and the quality of its research and analysis, but it lacks the administration experience of the public service. That’s the experience of learning what works and what doesn’t work, and where the laws of unintended consequences upset the most carefully-designed policies.

Perhaps there could be arrangements that give parliamentarians more access to the public service. Rather than a second personal adviser, perhaps there could be a public servant from one of the central agencies, such as Finance, seconded to work with a parliamentarian. That would be someone experienced and senior enough to have a sound grasp of policy, and who would have contacts in other agencies.

Or, in the general spirit of open government, the public service could be made more accessible to all. After all, it is easy to find the names, expertise, phone numbers and emails of academics, but it is well-nigh impossible for any outsider to make contact with a Commonwealth public servant. That’s why lobbyists and community organizations have staff in Canberra who develop networks and contacts: there is nothing so valuable to a lobbyist as his or her electronic address book, with contacts up and down the bureaucratic line.

While the rhetoric is about “open government”, the reality is that the public service is becoming more cloistered. There was once a regularly-updated document known as The Commonwealth Directory, which gave contact details for middle- to senior-ranking staff in government departments: an online version would be a simple innovation.

Lowy Poll – we’re feeling less safe

The annual Lowy poll, conducted before the election, reveals that over the last three years we have come to feel less safe when we consider world events. Ten years ago around 90 percent of us felt safe compared with only around 50 percent now. Australians now identify many threats to our vital interests: Russia’s and China’s foreign policies top the list, but there are many others including climate change, epidemics and political instability in the United States. Nevertheless 86 percent of us see the alliance with the USA as important for our security – almost the highest since the Lowy Institute started its surveys. That doesn’t mean we’re all the way with the alliance: in the event of a conflict between the USA and China 51 percent of us believe we should stay neutral, while 46 percent believe we should support the USA.

There has been a big jump in the proportion of Australians – now 75 percent – who think China could become a military threat to Australia in the next 20 years. We now see China more as a security threat than as an economic partner, and many of us are concerned about China’s influence on our political processes.

The poll has many other questions relating to security. We should be aware that the surveys for the poll were conducted between April 14 and 24, in the pre-election period, when Dutton had ramped up his belligerent rhetoric.

We may be more fearful, but we don’t seem to be turning inward. The poll has a set of questions relating to globalization. We remain positive towards globalization and increasingly we see free trade as good for Australia. On immigration, 68 percent agree that “Australia’s openness to people from all over the world is essential to who we are as a nation”.

There is a set of questions on climate change. A majority (60 percent) believe “Global that warming is a serious and pressing problem. We should begin taking steps now even if this involves significant costs”. This us up from a low point of 36 percent in 2012. We’re generally in support of strong policies to address climate change: for example 65 percent of us believe we should reduce our coal exports.

An alternative view on security

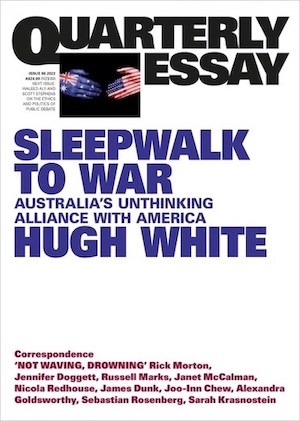

While the Lowy poll finds us to be firmly behind the US alliance. Hugh White’s latest Quarterly Essay Sleepwalk to War: Australia’s unthinking alliance with America, takes a realpolitik view of the alliance, essentially finding that the US does not have a strong reason to engage in a conflict in Asia or the western Pacific. He writes that “we have been too eager to accept, in the face of clear evidence, the comfortable consensus that America’s position in Asia is invulnerable, that its armed forces are unbeatable and that its commitment to Asia is unshakeable”. He believes that there is no inevitability of Thucydides Trap – the idea that as one hegemonic power gives way to another, war becomes inevitable. In fact there will not be a simple US-China change in relative position because the world is moving to a multipolar order.

He identifies AUKUS as an opportunistic post-Brexit commercial opportunity for the UK, into which the gullible and Anglophile Morrison government was sucked.

Essential Report: the honeymoon continues

The latest Essential Report would provide comfort to the Albanese government. We’re back to thinking Australia is on the right track, we support the 5.2 percent rise in the minimum wage, we assign most of the blame for the electricity and gas crisis to the previous government’s neglect, and we believe that the government should implement the climate change policies it took to the election (30 percent of us believe the government should be more ambitious). There are largely predictable partisan differences, but there are a few surprises: 41 percent of Liberal voters blame the previous government for the electricity and gas crisis, for example.

The Essential poll has some general questions on international relations, responses to which generally align with those in the Lowy poll (see the above post): 80 percent of us see the relationship with the USA as important.