Public policy

Human rights challenges for the Albanese government

Australians Sean Turnell and Julian Assange are in jail, in Myanmar and the UK. Turnell has been detained since the military coup early last year, and is now subject to fabricated charges of violating the official secrets law – one of the standard tactics used by authoritarian regimes. Julian Assange has been held in the high-security Belmarsh prison in the UK for three years, where he is contesting that country’s attempt to extradite him to the US, where, like Turnell, he faces charges relating to state secrets.

Amnesty International presents Assange’s case in a short statement: the charges against him are a threat to investigative journalism and he is unlikely to get a fair trial. Greg Barns has an article on Michael West’s site – Assange is still in jail – what can the new government do? – calling on Albanese and Wong to take up Assange’s case. “The early signs are the Albanese government is uncomfortable about the case” he writes. Writing in The Conversation Holly Cullen of the University of Western Australia and Amy Maguire of the University of Newcastle describe Assange’s legal situation and options in some detail, and discuss the diplomatic pressure our government could take in his case: UK government orders the extradition of Julian Assange to the US, but that is not the end of the matter.

One parliamentarian who kept the issue alive was South Australian Senator Rex Patrick. Unfortunately he was not re-elected. But Andrew Wilkie is still making his voice heard on Assange, as have some of the newly-elected independents.

Turnell and Assange are held in foreign countries – one a military dictatorship, the other a country that falls short from classification as a robust democracy.

But we too fall short, particularly in our protection of whistleblowers. The cases of Bernard Collaery and Witness K receive some publicity, but as Michael West reminds us there are many others – David McBride, Jeff Morris, Richard Boyle, Tony Watson, Benjamin Koh, Troy Stolz – to name a few, some facing criminal charges for exposing government corruption, others facing the threat of ruinous civil charges for exposing tax evasion and other forms of corporate theft.

“The old government had a penchant for persecuting people for doing the right thing” says Michael West, calling on the Albanese government to use its diplomatic powers to have Assange released, and to enact proper legislation to protect whistleblowers. In opposition Albanese and members of the shadow cabinet made the right statements – West’s 7-minute video concludes with clips of Albanese’s statements, including his assertion that “journalism is not a crime”, the main point in Assange’s defence, and his promises to fix the whistleblower laws.

On the ABC website Nassim Khadem has an article going into detail about criminal and civil charges brought against whistleblowers in Australia – Labor government urged to drop prosecutions against whistleblowers and ramp up protections – with contributions from respected human rights lawyers.

And on his Policy Post site Martyn Goddard goes further into human rights describing some of the previous government’s contempt for human rights, particularly as they should apply to refugees. He holds out hope that this government may bring us a charter of human rights: A nine-year fight against a government’s inhumanity.

How to increase household incomes by $3000 year

Ban gambling.

OK, a complete ban on gambling would be a little paternalistic, and historically Australians have always found ways around wowsers’ gambling restrictions. The SP bookie in the backroom of a country pub is a folk hero. Even if internet gambling can be better controlled, there are always VPNs.

Gambling has long been an aspect of Australian life, but as the Productivity Commission pointed out in its 2010 report on gambling, there is a case for strong controls on forms of gabling likely to result in gambling addiction. Poker machines and some forms of internet gambling, with short time cycles, with no limits on the number of cycles, with an easy tap into the gambler’s money, and often performed alone, pose much higher risks than traditional forms of gambling such as lotteries and horse racing. The Productivity Commission, using conservative assumptions, estimated the annual cost of problem gambling to be between $5 billion and $8 billion, while acknowledging that many costs, being hard to quantify, are not covered in its work. Besides financial costs there are others: for example gambling researcher Charles Livingstone has pointed out in The Lancet, that gambling debt is closely associated with suicide risk.

A less hectic form of gambling – Adaminaby racecourse

On a recent Sunday Roundtable the ABC’s Antony Funnell interviewed three experts on gambling – Charles Livingstone and Louise Francis of Monash University, and Kate Seselja of the Hope Project: The long hand of gambling in Australia. It was a wide-ranging 30-minute discussion on gambling. (Those who want hard data on gambling will find excellent summary data on the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare website Gambling in Australia, which has links to more comprehensive sources.)

Their discussion was mainly about the easy run Australian governments, mainly state governments, have given gambling interests in Australia, with specific attention to the scandals involving casinos – money laundering and breach of credit card regulations, particularly in relation to the Crown inquiry. That’s at the high end of the market. They also discussed gambling in pubs and clubs, almost entirely poker-machine gambling, at the other end of the market. They dissected the claims that the mega-clubs – typically the huge RSL clubs – bring benefits to the community – as if those same or greater benefits to community sports would not occur in the absence of these enterprises with their huge management expenses.

Unlike other flows of corporate donations, which are mainly to parties on the “right”, the Labor Party has been the main beneficiary of donations from the gambling industry. The other beneficiaries have been state governments, which collect $7 billion a year in taxes on gambling, $4 billion of which is from gaming machines.[1] The story of how states became so dependent on pokies goes back a long way to when New South Wales first liberalised regulations, leading other states to follow as their citizens drove or were bussed across state borders to gamble on the pokies. Western Australia is the only state that has been able to retain some sovereignty and stop the spread of pokies into the community: it’s a rather long drive from Perth to Eucla.

In some ways poker machines are to Australia what firearms are to America – a dangerous menace that has become politically entrenched. Any proposed move against poker machines is met with NRA-style hysteria about regional employment and support for community sports, without acknowledgement of the money they are sucking out of poor communities because of their disproportionate reliance on addicted gamblers. The other defence the industry can mount is that pokies provide entertainment for the working-class, and it is paternalistic for the elite political class to intervene.

The Commonwealth may wish to wash its hands of the matter, claiming that gambling regulation is a state matter. But the Commonwealth has taken on cost-of-living as an issue. Gambling losses in Australia are about $26 billion a year. That’s $1000 a head or $3000 per household. That’s an average across all households including those who never gamble. It’s all diverted from other consumption or from saving for a house deposit. About half of that loss is through pokies.

The Commonwealth may not have the direct means to ban pokies or to enforce strong controls, but it does have the lever of payments to the states with conditionality. Compensation to the states for doing without revenue from pokies would almost certainly be less costly than other means to ease cost-of living pressures.

1. Figures from ABS Taxation Revenue, 2020-21.↩

The Reserve Bank’s warnings

The media has given a fair bit of attention to the speech by Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe on inflation and monetary policy in which he made the strong statement that “the Board is committed to doing what is necessary to ensure that inflation returns to the 2 to 3 per cent target range over time”.

The case for holding inflation down to a low level is rarely explained, and the RBA makes only a weak case when it says “high inflation damages the economy, reduces the purchasing power of people's incomes and devalues people's savings. It is also regressive, hurting most those who are least well equipped to protect themselves”.

That’s less than convincing: indexation can be built into contracts and entitlements, and those who have become savers as a result of loose monetary policy rather than through thrift are not necessarily deserving special consideration. Against the costs of inflation are the terrible costs of a recession that may be brought about by harsh monetary policy. Monetary authorities should not have a carte blanche to throw everything against inflation without accounting for and justifying the economic costs of their actions.

The Governor’s speech mentions many of the causes of the present round of price rises, including the valid observation that “inflation is the rate of change of prices” (emphasis in original). Once the price of gasoline has risen as a result of the Ukraine war, once the price of lettuces has risen as a result of floods, once the problem of failing coal-fired power stations haas been solved, once the price of shipping has gone up as a result of once-off factors, there is no longer any reason to expect prices to go on rising.

More basically, monetary policy is supposed to control inflation by suppressing demand-pull factors. But when price rises come about through the cost of imports, including shipping costs, that aspect of monetary policy doesn’t work. Also, for some goods such as basic food, demand is fairly inelastic in the medium term. Higher prices are actually functional in encouraging a physical expansion in production.

The Bank seems to be justifying tighter monetary settings in anticipation of wage rises, as Saul Eslake explains on ABC Breakfast. A self-perpetuating feedback loop of higher wages leading to higher prices leading to higher wages and so on is undesirable. But why, at a time when profits are high, should the burden fall on wage earners? If the policy objective is to pull loose money out of the economy, a tax on excess profits, or higher royalties on resource companies, could do a better job. That’s a task for the government, not the Reserve Bank.

Housing – whatever the government does, someone will be inconvenienced

After electricity supply, relations with the Pacific, falling real wages and incipient inflation, the other policy mess this government has inherited from its predecessors is housing.

Housing remains absurdly unaffordable, but too rapid a fall in housing prices could leave many recent house buyers with high mortgage stress. Homelessness is unacceptably high, and there is an under-supply of public housing. Many people are facing the challenge of re-building after floods and some people have not been able to re-build after the bushfires two and a half years ago. In the building industry shortages of skilled labour and of crucial materials are delaying many jobs, ruining businesses’ cash flow and driving them to bankruptcy, in spite of high demand. Even when materials are available prices are rising rapidly, rendering fixed-price contracts unprofitable.

The general consensus, even from those who have been pushing up the housing market in the past, is that the property boom is over, although nominal prices could possibly rise in a high-inflation environment. Those same insiders believe Sydney will lead the rest of Australia in falling house prices.

Stephen Koukoulas, on the other hand, believes it is possible that housing prices could still rise. He demonstrates that in previous periods of rising interest rates there have still been significant rises in house prices. Joey Moloney and Brendan Coates from the Grattan Institute present a more mainstream prognosis: this time rising interest rates will bite, because they come off a low base and because households are carrying larger mortgage burdens (repayments as a share of income) than they were in earlier times. Their analysis is in The Conversation: The housing game has changed – interest rate hikes hurt more than before.

Even before interest rates started to rise there were signs that the housing market was cooling. The recently-released new ABS series Total value of dwellings, which goes up to March this year, reveals that house and unit prices have been falling in Sydney and Melbourne.

Getting even larger according to the RBA

The Reserve Bank has dug into the housing market, presenting its findings in a speech by Assistant Governor Luci Ellis: Housing in the Endemic Phase. The bank’s researchers find that after a period of strong demand for inner-city living, some of us at least may be heading back to the suburbs. Since the start of the pandemic, average household size – the number of people per household – has fallen, and in general we have been demanding more space. Also the price premium for inner and middle city houses relative to houses in the suburbs has fallen. The RBA confirms that the construction industry is reaching capacity, and that there is an increasing backlog in demand for housing. Although not mentioned in Ellis’s speech, this raises the question of immigration. If immigration resumes at a high level, as many businesspeople are urging, will their demand for housing worsen affordability or will they fill skill shortages and increase supply?

It is notable that the New South Wales government has introduced a shared equity scheme for housing, broadly similar to the scheme Labor took to the election (and which attracted ridicule from the Coalition). It is also moving to replace stamp duty on house sales, a tax that is borne by home buyers, with a general tax on all property. Such a scheme is already being phased in in the ACT.

Early schooling – a long-term investment

“In the next 10 years every child in Victoria and New South Wales will experience the benefits of a full year of play-based learning before their first year of school”.

That’s an extract from the statement of intent released jointly last week by the premiers of New South Wales and Victoria. Details of how this initiative will play out are on the websites of the New South Wales Premier and the Victorian Premier.

Benita Kolovos and Tamsin Rose, writing in The Guardian, summarise and compare the two plans. They have to fit in with slightly different systems, and the Victorian scheme will be up and running before the New South Wales scheme: What the new year of preschool education means for parents and children.

Wendy Boyd and Michelle Neumann explain the schemes’ policy principles in a Conversation article: A $15 billion promise of universal access to preschool: is this the game-changer for Aussie kids?. The main educational feature is that they will be play-based: differential calculus, Latin and nuclear physics are not on the agenda. And importantly the policy intention is twofold – to help children build skills for life and to release parents for paid work. In fact the emphasis in the governments’ publicity is on the former.

Many commentators have expressed amazement at the cooperation between two premiers, one Liberal, the other Labor. That’s not unusual at a state level: perhaps people are surprised because it is in contrast to the hyper-partisanship displayed by the federal Coalition in office over the last ten years.

What is unusual, however, is the commitment to an expensive reform that won’t show dividends for many years, and even then those dividends, although substantial, will hardly be noticed – more people going on to TAFE or university, fewer young people committing crime, fewer teenage pregnancies. There will probably have been several changes in government in each state, and Dominic Perrottet and Daniel Andrews will be well past their years of representative politics.

Public health – rising Covid-19 deaths

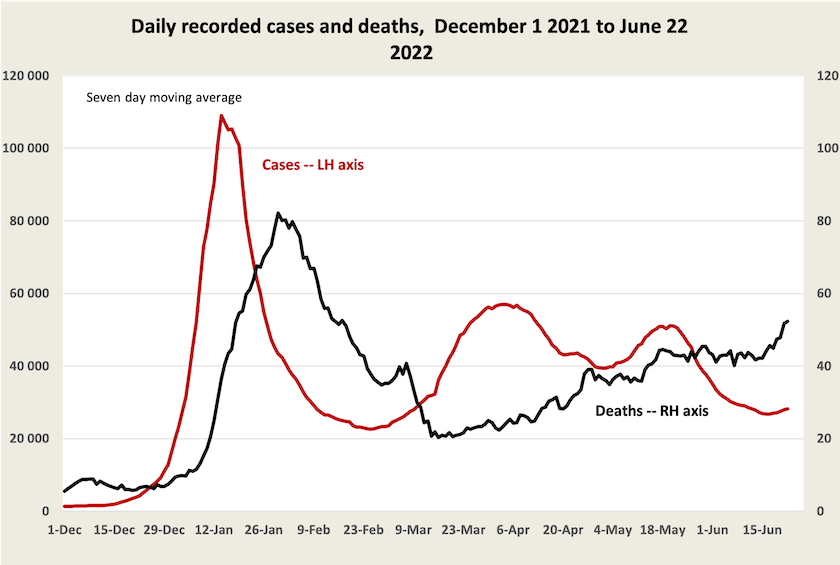

Recorded Covid-19 cases have started rising again, possibly as new sub-variants of Omicron spread, and deaths are rising steeply. Deaths fell about three weeks after the January wave, but they aren’t falling after the April and May waves.[2]

At 50 deaths a day, or 2.0 per million population, Australia has a very high death rate in comparison with other “developed” countries. In the European Union daily deaths are now 0.7 per million. There are similar rates in the UK and the US, and in Singapore, South Korea and Japan daily deaths are down to around 0.2 per million – one tenth our rate.

Notably in New Zealand deaths are still high, at 1.7 per million. This suggests that the winter season may have something to do with our high death rate. In the same context Victoria’s death rate (3.0 per million) is higher than the rate in New South Wales (1.5 per million), which is higher than Queensland’s (1.5 per million).

Also, Australia’s death rate per recorded case is rising. By early May the death rate per recorded case had fallen to 0.050 percent, or one in every 2000 cases, but it is now up to 0.164 percent, or one in every 610 cases.[3] The same data suggests that the death rate per recorded case is higher in Victoria than it is in New South wales. In Victoria you’re much more likely to die than if you pick it up in New South Wales. (Are the people of Echuca-Moama aware of this?)

One possible explanation for Australia’s rising death rate is that there is a bias in the official figures because they are increasingly recording only the more serious cases, as some analysis by the Kirby Institute reveals.

At the end of February last year, official figures showed that 12 percent of Australians had been infected with Covid-19. Research by the Kirby Institute, using antibody analysis on a statistically significant and well-structured sample of the population, reveals that the actual figure was at least 17 percent. The highest rate of infection – 27 percent – had been among people aged 18 to 29.

Interviewed on ABC Breakfast on Monday John Kaldor from the Kirby Institute described the study, and suggested that cases could be twice as high as are picked up in officially recorded figures. That’s higher than the 17 percent picked up in the February study, but it’s a credible figure. The Omicron wave, which has been around since December, is manifest in less severe illness and therefore more asymptomatic infections than earlier strains; we came to depend more on RAT tests that have more false negatives than PCR tests; there was a shortage of RAT tests; and people have probably become less diligent in reporting positive cases to authorities. (9 minutes) That factor of two is also consistent with suggestions earlier this year by Norman Swan that many cases are being missed.

The Kirby Institute will conduct another set of tests in June, which is likely to show a higher incidence of undetected cases, as Kaldor suggests. Even if the factor is only 2.0, it would indicate that around two-thirds of Australians have been infected in the Omicron wave.

It is surprising that the media is not reporting our high and rising death rate. Is it that a phenomenon developing over several weeks just doesn’t fit into the media’s 24-hour news cycle?

2. For comprehensive data on recorded cases, deaths, hospitalizations and more, see the website maintained by Juliette O’Brien and her colleagues: Covid-19 in Australia. Data on vaccination is on the ABC’s vaccine tracker, maintained by Inga Ting and her colleagues. The Guardian’s data tracker has further select data, including reported infection rates in regions within states. ↩

3. These figures are for the number of deaths, smoothed over 7 days, divided by the number of cases, similarly smoothed, three weeks earlier. ↩