Public policy

Economic outlook: a more frank assessment than the PEFO

Steven Kennedy, Secretary of Treasury, has given a frank, clear and detailed assessment of Australia’s economic and fiscal position and prospects in a speech to Australian business economists. It’s titled Post-Budget economic briefing – opportunities and risks, but it could also be read as setting the scene for the budget to be presented in October this year. It’s a much clearer document than the convoluted Pre-Election Economic and Fiscal Outlook.

The speech covers the main pressures on the world economy: a post-Covid surge in demand for goods contributing to demand-side inflation, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine causing a spike in food and energy prices, and China’s zero-tolerance response to Covid disrupting output.

Australia will be affected by the same developments. Treasury sees an extended period in which there will be low wage growth, and it comes back to the need to boost productivity.

We realize that this is not the speech Treasury would have prepared for the previous government when we read about the need to make “investments in human capital to ensure Australians have the right skills to enable diffusions of frontier technologies and methods.”

We also see the stamp of the new government in the fiscal section of the speech. The phrase “budget repair”, a euphemism for austerity, does not appear. Instead, government debt will be reduced through economic growth. (The speech includes a marvellously informative chart showing how economic growth and direct fiscal measures have contributed to changes in net government debt, going back 100 years to 1920.) There is a chart on projected and largely locked-in demands for government spending over the next four years. NDIS is the big one, followed by aged care, defence, health and infrastructure. (Its estimate for the growth in health expenditure is modest. Is Treasury under-estimating the need to spend much more on health?)

There is guardedly ambiguous language on tax cuts: we shouldn’t expect there to be any. Treasury seems to be sceptical about economic growth as the main path to reducing government debt, however. Rather “a more prudent course would be for the budget to assist more over time”. Were the Coalition still in office we would expect to see that statement followed by a reference to the need to cap taxation at 23.9 percent of GDP (one of the most absurdly unjustifiable arbitrary numbers since Douglas Adams’ “42”). Rather, it is followed by a call to raise more revenue:

Ongoing review of the tax base and tax expenditures to ensure the tax system remains adequate to fund spending commitments and is equitable including from an intergenerational perspective will be important given the pressures to raise more revenue over time.

Note the references to “tax expenditures” which are dominated by superannuation tax breaks, and to intergenerational equity. These hint that in the budget there will be some rollback of the unjustifiable privileges enjoyed by so-called “self-funded” retirees. Hopefully that will be through measures more equitable, less distortionary, and less easily evadable than the dopey idea of scrapping franking credits that Labor took to the 2019 election.

So much for the Coalition’s “gas-led recovery”

In a neat condensation of the factors driving the gas and electricity price spike Tony Wood of the Grattan Institute explains the 4 reasons our gas and electricity prices are suddenly sky-high, in The Conversation. Failures in coal-fired power stations top the list.

Watch the spin

Tim Nelson and Joel Gilmore, also writing in The Conversation, suggest 3 ways the government can ease pressure on power bills. Nothing in the short run, but the government should “turbocharge renewable energy efforts” and develop a capacity reserve independent of the fossil-fuel generators. It should also get the ACCC to look at the generators’ shortages – did they schedule their pre-winter maintenance too late and get caught out by the early onset of winter, was it the unreliability of 40-year old equipment, or was it price gouging? They present a neat table showing the shortfalls in the generators’ capacity, a reading of which suggests both breakdowns and gouging may be present. Giles Parkinson, writing in Renew Economy, goes into detail about the disruptions over a short period, explaining how our present mix of generating capacity is leading to such high price volatility: Market chaos as outages push coal output to record low, despite new wind peaks.

Also writing in Renew Economy Michael Mazengarb explains why, as most people in eastern Australia face a big rise in electricity prices, in the ACT there will be a small reduction in prices, because it 100 percent of its electricity is from renewable energy: ACT reaps dividend from 100 pct renewables as energy bills fall despite market chaos. That’s a net self-sufficiency, because it balances its exports of electricity from renewable sources with its imports from other sources. With our present generation and storage mix it would not be possible to scale the ACT model up to a national level, but it does illustrate the cost advantage enjoyed by renewable energy.

There are other proposals on offer from various parties. Richard Denniss, writing in The Guardian, suggests taxing windfall profits currently being enjoyed by the gas companies and spending the proceeds to accelerate the shift to renewables and to get households and companies off gas. If Britain’s Conservative government can do it, surely we can do it too? (But is the fossil-fuel industry as politically embedded in the UK as it is here?) Tony Wood of the Grattan Institute suggests that the threat of a windfall profit tax to be levied in the future can be used to obtain lower gas prices in the short-term. The Guardian’s Adam Morton looks at the Coalition’s line that we should now be considering nuclear power as a means to achieve net zero. Maybe, but in view of nuclear power’s long lead time, isn’t it a bit late to start thinking about it? On the present trends of falling costs of renewable generation and storage, by the time a nuclear plant is commissioned it would be quite uncompetitive. And former Western Australia premier Colin Barnett, while making the point that the gas we’re exporting belongs to Australia, and gloating about his state’s bipartisan policy of gas reservation, suggests building a gas pipeline to connect the Western Australian gas fields with the eastern states’ pipeline network. (That was the vision of Minerals and Energy Minister Rex Connor in the Whitlam Government fifty years ago – a vision that was so viciously attacked by the Coalition opposition that it was used as an excuse for the Coalition-controlled Senate to block supply.)

Although there is little that can be done about the immediate problem of a spike in energy prices, the emergency meeting of energy minister has dealt with the need to have capacity in electricity supply to deal with demand-supply imbalances, and the need to hold gas reserves. The previous government made no progress on these problems because it was insistent on prolonging the lives of coal-fired power stations. Tony Wood, speaking on the ABC’s The Money program, is impressed by the way the Commonwealth, with cooperation from states, has come to a set of arrangements so rapidly. Although many would like to see stronger immediate action against energy companies, the government is well aware of the possibility that such action would precipitate a claim that the new “left” government in Australia poses sovereign risk. (Wood’s session is in the first 12 minutes of the program.)

Wisely the government isn’t going all out to blame the Coalition for our present crisis: that would be a gratuitous statement of the obvious. But many journalists are pretending that the climate change wars just happened, using constructions such as “climate change became a matter of identity politics”, or more misleadingly asserting that both main parties were responsible. Writing in The Guardian in 2017 Mark Butler, now the Minister for Health and Aged Care, set the record straight, in a summary of his book Climate wars. His article How Australia bungled climate policy to create a decade of disappointment describes how, since the election of John Howard as prime minister in 1996, the Coalition, with support from sections of the media and the fossil fuel industry, went all out to make climate change a way to differentiate itself from Labor, in defiance of science and the national interest.

Missing from the public debate is any criticism of the monster known as the National Electricity Market, in which, late last century, the old vertically-integrated state utilities were broken up into generating, transmission, distributing and retailing businesses, and privatized.

Separating out the generators and subjecting them to competition made sense, as did increasing the grid’s interconnectivity, but the rest was economic idiocy. It ignored the transaction costs, the regulatory costs and the duplication costs of the new arrangements, and it ignored the fact that the technology of transmitting and distributing electricity is about 100 years old with very little to be gained from any of the supposed efficiencies resulting from privatization. On the ABC’s Drive program Western Australia’s Energy Minister Bill Johnston explains to hapless easterners the benefits of that state’s gas reservation policy, and the benefit of not having been brought into the NEM: its generators have been privatized and are subject to competition, but it retains the state-owned integrated transmission, distribution and billing system. (13 minutes)

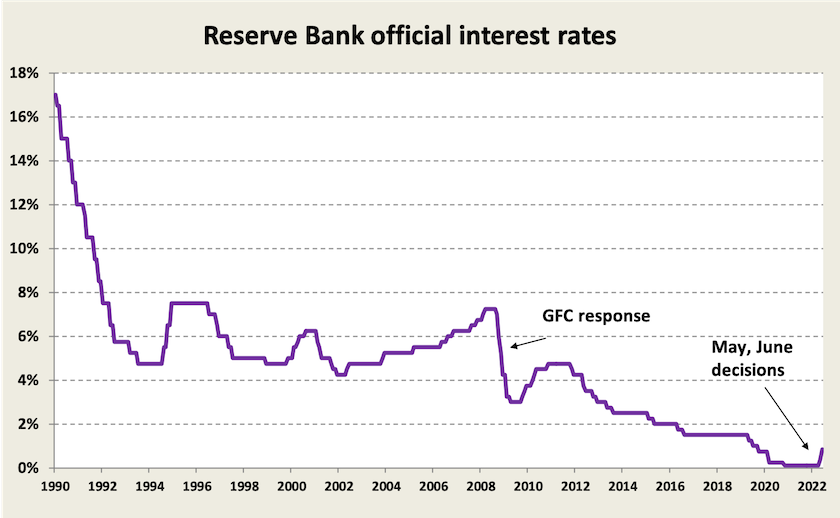

Interest rates – right decision, poor reason

No-one was surprised by the Reserve Bank’s decision to lift the official interest rate (the “cash rate target”), but many economists were surprised by the 50-point rise, from 0.35 percent to 0.85 percent. It’s 22 years since the RBA has lifted the interest rate by 50 basis points, and that was from a relatively high level, from 5.00 percent to 5.50 percent. The rise from the present low base is likely to be far more significant for highly-indebted households and businesses.

A rise in the official interest rate was inevitable, because the real interest rate – that is the nominal rate as posted by the RBA minus inflation, has been negative or just above zero for most of the last five years, and even with this rise it will still be negative -- around minus two to three percent.[1] For most of the period 1990 to 2015 the real rate has been around plus two to three percent.

The simple story is that official and real rates became low because of the decisions to lower rates during the pandemic. Negative real rates, which essentially fine people for holding cash, gave an incentive for people to spend: they’re a stimulatory measure. They now need to be brought back into positive territory. But the story is not so simple, because the RBA actually started dropping rates in May 2019, long before there was any pandemic. That’s because the economy was already sluggish and the labour market was flat.

From the middle of last year there has been a case for the RBA to raise rates: the government had thrown around billions in fiscal stimulus, and the Covid recession had not been as bad as expected. But because the RBA had promised to hold rates until 2024 it was reluctant to raise rates. It seems that the Morrison government’s reckless pre-election spending gave the RBA an excuse to break that promise in May when it cautiously raised rates by 0.25 percent. Also, not to have done so would have appeared to be a little too partisan.

But that’s not the story in the bank’s media statement accompanying its most recent decision. It acknowledges one-off cost factors pushing up prices – supply chain disruptions and the war in Ukraine – but otherwise it is about a reaction to strong demand-side factors, including strong employment growth and early signs of a growth in wages.

The problem with that narrative is that there is scant evidence for the textbook inflationary spiral of increasing wages leading to increasing prices leading to increasing wages … In fact all the loose money seems to have gone into corporate profits rather than wages.

Policymakers – the RBA’s staff and board, public servants in Treasury and Finance, ministers and academic economists – need to think carefully about monetary policy and inflation. The idea that a rise in indices of inflation (such as the CPI) beyond X percent should be met with a rise in interest rates, has been part of the received wisdom for many years, but its simple application generally results in the huge economic cost of unemployed labour, unused capital capacity and cancelled investment plans.

Inflation is generally an indicator of an economy’s structural weaknesses, and it is usually better to attend to those weaknesses than to the symptom. What shows up as “inflation” in indicators such as the CPI is often a re-alignment of relative prices, leading to a welfare-improving re-allocation of real resources. A rise in gasoline prices, for example, will lead to an efficient re-allocation of expenditure as people change their vehicle choices and travel modes.

Even if there is economy-wide inflation it is not an unmitigated evil, because inflation helps unstick real wages and prices. And it erodes the real value of debt. Admittedly that’s to the detriment of savers, but the expectation of inflation nudges savers to do something more useful with their money than putting it into fixed interest. On ABC’s Breakfast program on Wednesday John Quiggin questioned the RBA’s 2-3 percent target. Such is the entrenchment of the idea that any inflation above 3 percent is bad that Patricia Karvelas seems to have been shocked when Quiggin suggested that 4 percent may be a better target for the RBA.

That doesn’t mean the RBA shouldn’t have raised rates, but its reason for doing so is a lame one. Ideally as rates rise there should be a countervailing response from the government to deal with supply shocks, and to push for higher wages for the most poorly-paid workers. That way there is the possibility that real economic activity can be maintained.

1. The real interest rate is actually given by the formula ((1 + nominal rate)/(1 + expected inflation) – 1). But because we don’t know what expected inflation is, and because most journalists are challenged by the mathematics of division, the real interest rate is usually estimated as (nominal rate – CPI inflation). ↩

A Warning from the World Bank

The World Bank’s Global Economic Prospects reads like a prophecy of the Ten Plagues of Egypt.

OK – not quite ten, but the war in Europe with its consequences for food and energy prices is one of the main contributors to its forecast of a sharp fall in global growth, particularly in low-income countries. Where there’s hunger and a return to economic hardship there’s conflict. Where there is conflict there will be refugees. These threats to prosperity and security are on top of, or consequent to, the ravages of Covid-19, which is still spreading among many unvaccinated populations.

Another threat it sees is stagflation (a never-ending cycle of wage and price rises without any real growth), and the possibility that in their monetary and fiscal responses to stagflation “developed” countries will precipitate a global recession – a repeat of the problems in the 1970s. Rises in interest rates will hit indebted countries particularly hard.

It has a set of recommendations, including attention to the supply of essential commodities and debt relief. Unsurprisingly one of those recommendations is to speed the transition to low-carbon energy sources.

The forgotten public service

Unlike his Coalition predecessors Albanese hasn’t purged the senior ranks of the public service. Phil Gaetjens, head of the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, who had been unwavering in his partisan loyalty to Scott Morrison, had the decency to vacate the position once the election result was clear, leaving the incoming government with only one department head position to fill.

The expectation was that the government would fill the position with a transfer or promotion from within the public service, but Albanese’s choice was Glyn Davis, professor at ANU’s Crawford School of Public Policy and formerly Vice-Chancellor of the University of Melbourne. Wikipedia’s biography on Glyn Davis reveals him to have a lifelong commitment to scholarship and to the public purpose. We are reminded that he presented the 2010 Boyer Lectures on “The Republic of Learning: higher education transforms Australia”.

On last weekend’s Saturday Extra Geraldine Doogue interviewed Andrew Podger, former Public Service Commissioner and now honorary Professor of Public Policy at ANU, about the public service reforms we can expect from the Albanese government: Glyn Davis and the Australian Public Service. The government has already made it clear that it is committed to bringing work back to the public service rather than relying on expensive consultants who lack the experience, professionalism, political disinterest and deep knowledge of career public servants. The discussion also ranged over the way recent governments have bypassed the public service for policy advice, often relying on the advice of partisan political staff.

In the interview Podger referred to what is known as the Thodey Review, a review of the public service, commissioned by the Turnbull government and presented in December 2019. (Glyn Davis was one of the reviewers.) To quote, the review made a number of specific recommendations around the public service’s need to:

- work more effectively together, guided by a strong purpose and clear values and principles;

- partner with the community and others to solve problems;

- make better use of digital technologies and data to deliver outstanding services;

- strengthen its expertise and professional skills to become a high-performing institution;

- use dynamic and flexible means to deliver priorities responsively, and

- improve leadership and governance arrangements.

These appear to be no more than what we would expect from our public service, but that’s the very point of the Thodey Review: the public service has not been meeting these reasonable expectations.

The Morrison government, having little respect for the public service, largely ignored the review’s recommendations.

Health policy: it’s not only Covid that’s overloading our hospitals

This election was unusual in that health and Medicare did not feature strongly in the campaign, in spite of the pandemic’s continuing presence, and in spite of health policy usually being one of Labor’s political strong points.

That’s not to say it has escaped public awareness. We are well aware of the load on hospitals imposed by Covid-19 and now by a resurgence of influenza. And we are becoming more aware of a shortage of GPs, particularly if we live somewhere distant from our large cities.

The Australian Medical Association is calling on the newly-elected Commonwealth government to increase funding for hospitals and to make other reforms in health services. A “senior health leader”, writing anonymously in Croakey, makes an impassioned plea for attention to the problems in our hospitals, and more serious public health measures, on behalf of all overworked and highly-stressed health workers coping with barrages of aggression from patients.

On the ABC’s Breakfast program Norman Swan points out that the current pressure on hospitals is not only about Covid-19 and influenza. It has been building up for some time, and it relates largely to problems elsewhere in our fragmented arrangements for the delivery of health care. (I always refrain from writing about our health care “system”, because it isn’t a system).

Swan stresses that much of the problem goes back to a shortage of GPs. That’s a significant cause of excess stress on hospitals. If people with chronic illnesses, for example, don’t get early attention from GPs they are likely to present at hospitals with serious conditions. It’s not as if our universities aren’t graduating enough GPs, but the profession isn’t attractive, because of comparatively poor pay and intolerable workloads.

Swan calls for significant reform, to bring about more integration between primary health care and hospital care, including an alignment of incentives between Commonwealth and state governments. (Because the Commonwealth funds ambulatory GP services and the states bear most of the cost of public hospitals, there are incentives for cost-shifting.) One possibility to be considered, Swan suggests, is for the states to take over responsibility for funding and delivering GP services, which would give them an incentive to use GPs as a means to reduce the load on hospitals. (That is the situation in Canada, which operates a publicly-funded health care system with federal funding and control but province-level administration.)

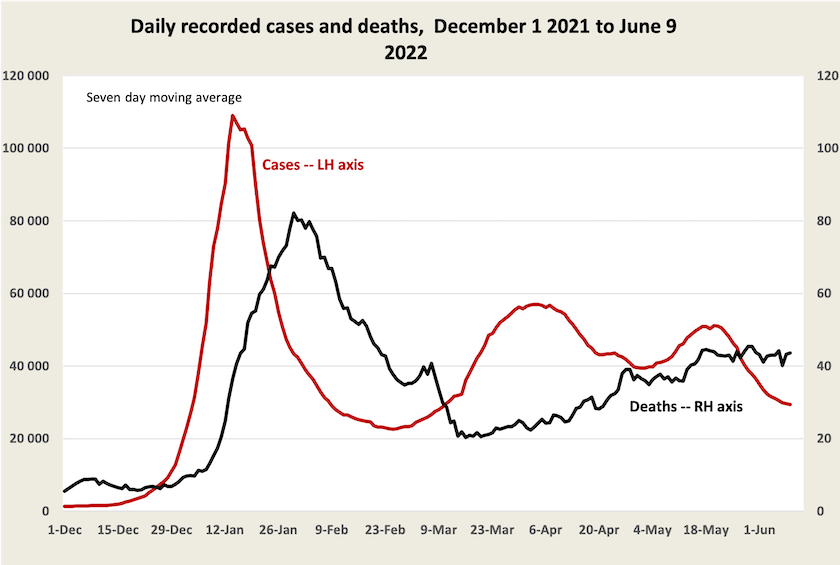

Covid-19

Covid-19 cases are falling, but deaths are holding at about 40 a day, indicating that it is still putting a heavy stress on hospitals.

Among our largest states, while cases and deaths have been falling in New South Wales and Queensland, the situation is seriously different in Victoria. In New South Wales the daily rate of new cases being recorded is 800 per million population; in Victoria it is 1300. In New South Wales the death rate per recorded case (with a three-week lag) is 0.01 percent, or 1 in 1000, while in Victoria it is 0.15 percent, or 1 in 700.[2][2] In Victoria not only are proportionally more people contracting Covid than in other large states, but more of those who contract it are dying from it.

Epidemiologists and the media are well aware of Victoria’s high incidence of cases and its high death rate, but there are no firm reasons on offer.

2. For comprehensive data on recorded cases, deaths, hospitalizations and more, see the website maintained by Juliette O’Brien and her colleagues: Covid-19 in Australia. Data on vaccination is on the ABC’s vaccine tracker, maintained by Inga Ting and her colleagues. The Guardian’s data tracker has further select data, including reported infection rates in regions within states. ↩