Economic policy

A finance minister’s tale

“We are inheriting a very serious set of economic and budget challenges” says Finance Minister Katy Gallagher in an extended (16-minute) interview with Insiders host David Speers.

In some ways the interview follows a predictable path: Speers digs for hints of what’s to come in the budget in October, while Gallagher stresses the burden of debt inherited from the previous government, reminding us that half of that debt had been accrued before there was any hint of a pandemic.[1]

It differs from the established pattern in two ways, however.

If she had been following her Coalition predecessors she would have presented a tirade of accusations against the outgoing government for their fiscal recklessness. Instead her approach was deadpan: she referred to the need to run a tough audit through the budget, but not in an accusatory tone. The election campaign is over.

The other departure from the standard script was to emphasize the need to differentiate between government spending that is immediately consumed and that which provides ongoing benefits. As Labor has stressed during the campaign, rather than looking at fiscal aggregates we should consider the quality of government spending.

An accountant might correctly say that this is simply the conventional distinction between recurrent and capital expenditure, and that it is generally unwise, in the long term, to borrow to finance recurrent expenditure.

Gallagher’s point, however, is that much of what is classified as recurrent by accounting convention actually produces future benefits, and is more in the nature of investment than recurrent spending. Spending on child care, which releases parents to engage in the paid workforce, is one such example, as is spending on education and training generally. Another consideration (which she didn’t mention) is that grants to the states for capital purposes are generally recorded as recurrent on the Commonwealth’s books.

In this emphasis on quality of expenditure Treasurer Chalmers and Finance Minister Gallagher are taking us beyond the puerile obsession with the big numbers in the budget, and into a consideration of the purpose of public spending, reminding us that the budget is about economics and not just fiscal impression management.

There is nothing radical in this: until around the mid-1990s the Commonwealth budget had a great amount of detail about how government spending was allocated between different programs and sub-programs , between personal transfers (such as pensions) and spending on goods and services (such as health care), but one of Treasurer Costello’s “reforms” was to strip out such detail and to focus purely on financial detail.

These were her departures from the established pattern, but her most important point was within the established pattern, when she mentioned some of the big recurrent expenditures, specifically health, aged care and the NDIS.[2]

A common aspect of all these human-service programs is that they are intrinsically labour-intensive. That means that, if the government is to maintain standards of service in these functions, they are going to cost more into the future, not just in absolute terms, but also as a proportion of GDP – and in turn that means we will have to pay higher taxes to finance them. This is in effect an example of what is known as Baumol’s Law – named after the economist William Baumol.

Baumol explained that in a modern mixed economy substitution of capital for labour has brought about tremendous improvements in labour productivity for most goods and services produced in the private sector, but that such substitution has not been so easily applied in the public sector because many government services are intrinsically labour-intensive. While the real (inflation-adjusted) price of cars, air travel, appliances, telecommunications and so on falls, the relative price of nursing, aged care, child-care, policing and teaching rises. As a corollary, if the mix of private and public goods in the economy is to be maintained, we will all have to spend relatively more on public goods and relatively less on private goods (even if we keep on spending more on private goods in absolute terms.) And that means higher taxes, if we adhere to the reasonable principle, implied by Finance Minister Gallagher, that we should not finance recurrent expenditure with deficit funding.

Conservatives who have a visceral hatred of taxes and of the whole public sector refer to Baumol’s Law as Baumol’s cost disease. Liberals are more inclined to refer to JK Galbraith’s observation of private affluence amid public squalor.

In most prosperous democracies governments have maintained the balance between public and private prosperity by increasing taxes. But among prosperous democracies we have tried to get by with almost the lowest taxes of all such countries, while our labour-intensive government services are struggling with constrained budgets, under-staffing and pay scales that are inadequate to attract and hold staff.

Chalmers and Gallagher are right in pointing out that the Albanese government has inherited a big fiscal deficit, “with nothing to show for it”. Will they also point out that they have also inherited the management of an economy with plenty of capacity to raise taxes without distorting (indeed improving) resource allocation?

1. The Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook presented in December 2019, estimated net debt of $392 billion, or 19.5 percent of GDP at the end of 2019-20. The Pre-Election Economic and Fiscal Outlook presented in April this year, estimated net debt of $632 billion, or 27.6 percent of GDP at the end of the current 2021-22 financial year, rising to $865 billion or 33.1 percent of GDP by 2025-26. There is often reference to a “trillion dollar debt”, which is gross debt – $977 billion at the end of the current fiscal year, rising to $1169 billion by 2025-26. ↩

2. Many of these programs deliver benefits for the whole society as well as for individual recipients, in that they allow more participation in the paid workforce. So even for these programs classification as “recurrent” tends to downplay their value. ↩

The Reserve Bank – it needs outsiders to have a look at it

A group of independent academic economists have written an open letter to Treasurer Chalmers, asking that the government’s proposed review of the Reserve Bank be conducted by someone outside the country. Their argument is that the financial establishment in Australia – including university schools of economics – are so used to the present arrangements that it is hard to find anyone who can undertake a detached review.

The letter itself is about process. On the ABC’s Breakfast program Warwick McKibbin, one of the signatories and who himself was once on the bank’s board, hints at some of the issues on signatories’ minds: Calls for a foreign eye on the RBA. The RBA mission of targeting inflation, specifically in a 2 to 3 percent range, was set after the 1990s recession: is it still the right focus? The bank’s board is dominated by businesspeople, who have their own perspectives: should its composition be wider? Does the board, in making its decisions, draw on an adequate range of advice, including the expertise of its own staff, or is it too dependent on carefully-prepared agenda papers vetted and cleared up the line?

Also related to the role of central banks is a short presentation by IMF Director Kristalina Georgieva who tells us how to avoid a global recession in a presentation to the World Economic Forum at Davos. She acknowledges the need for central banks to be independent, but she also calls for better integration of monetary and fiscal policy, and is critical of the consequences for the poor when central banks use blunt instruments to combat inflation. That’s quite a strong statement for the IMF to make.

AGL’s failed demerger raises basic questions about capitalism and corporate governance

Just a week after the change in government the board of AGL announced that it was abandoning its demerger plan – a plan that would have seen its retail business and power generation business separated into two separate companies. It also announced that four directors were resigning, including its chair and its CEO.

The plan was to have been voted on at a special meeting on June 13, but it had become evident that shareholders – institutional shareholders, individual shareholders, and major shareholder Mike Cannon-Brookes – did not intend to support it.

Cannon-Brookes became a substantial shareholder earlier this year, when he made a takeover offer for the company, conditional on the company phasing out its coal-fired plants by 2030. The board rejected the bid. In the roundup of 25 February is an account of the offer and the political pressure on the board from then Prime Minister Morrison and Treasurer Frydenberg to reject the offer. This was not the first time the Coalition government had interfered in the company’s operation: there is strong evidence that in 2018 then Environment Minister Frydenberg successfully pushed the board to sack CEO Andrew Vesey, who was taking the company out of coal and into renewable energy.

The demerger was essentially a plan to keep its large coal-fired power stations in operation until the very end of their lives. It planned to keep the 2600 MW Bayswater station going until 2035 and the 2200 Loy Yang station until 2045.

On the ABC’s program The Business there is a 12-minute interview with Cannon-Brookes, who provides a full briefing on the present situation. He intends to improve the company’s governance, and does not rule out making another takeover bid. He re-asserts his belief that we can have a 100 percent renewable energy-powered electricity sector by 2030, making his case in straight business terms. Writing in The ConversationMark Humphrey-Jenner of the University of New South Wales provides a further explanation of the finances of the AGL situation: Australia’s biggest carbon emitter buckles before Mike Cannon-Brookes – so what now for AGL’s other shareholders?

The business case against the board is strong. In 2018, before it scrapped Vesey’s plan, its share price was $22.50. It slid to a trough of $5.10 in late 2021, before partially recovering to around $8.50. (Undoubtedly the presence of a takeover offer helped boost the share price.) Commenting on the Board’s performance, particularly its contempt for its shareholders’ desire to see it make a faster transition to renewable energy, the Australasian Centre for Corporate Responsibility has issued a scathing press statement criticising the AGL board: “The current board of AGL wasted 18 months on the demerger, and five years of underinvestment in renewable energy”.

With the need to fill four board positions and the possibility of another takeover bid, there will be plenty to keep the business press busy. But there are three more basic issues about public companies that should get an airing.

One is the relationship between governments and board members. That relationship should be at arm’s length, and board members should not allow their own political alignments to influence the way they manage the companies for which they are responsible.

Another is about directors’ obligation to manage in the interest of the corporation’s owners – the shareholders. Perhaps an approach of wringing out the last few kWh from old power stations may deliver an earlier cash flow for shareholders than investing in renewable energy, but shareholders, particularly those saving for retirement, may prefer a later but more assured cash flow (particularly if the short-term option helps wreck the planet). Economists will recognize this as a principal-agent problem, relating to the fact that people investing either directly or through superannuation funds generally have lower discount rates influencing their choices than players in the financial markets. Although there is the maxim that boards should maximize returns to shareholders, that is not a simple, clear-cut objective when one considers the time span of those returns.

And a third issue, related to the first two, is the complacency and risk-aversion of managers in companies that have secured a strong position in the market. In an article in The New Daily about the power of monopolies and oligopolies in Australia – We all lose when monopolists prosper – Alan Kohler singles out AGL. “This week’s humiliation of AGL is an example of the pitfalls of this – companies become satisfied, incurious and lazy, devoting themselves to milking monopoly rents while expending as little energy as possible”.

National accounts – impressive figures, but what about the workers?

National accounts, released on Wednesday, show GDP growth at 0.8 percent for the March quarter this year and 3.3 percent for the 12 months to March.

This was well above expectations – it’s amazing how the economy has shown an improvement just ten days into a Labor government’s term of office!

The most encouraging figure is a growth of 1.7 percent in GDP per hour worked in the March quarter, or 2.8 percent over the year. GDP per hour worked is a rough indicator of labour productivity, and an increase in labour productivity points to the economy’s capacity to pay higher wages. But before we get too excited it should be noted that much of our economic growth results from three sources that are not really related to productivity: improvements in our terms of trade associated with higher world prices for agricultural and mineral commodities; pre-election fiscal stimulus payments; and consumers spending some of the savings they accumulated during the worst of the pandemic. Real improvements in productivity are a different matter. But if we are earning more per hour, why are wages not rising?

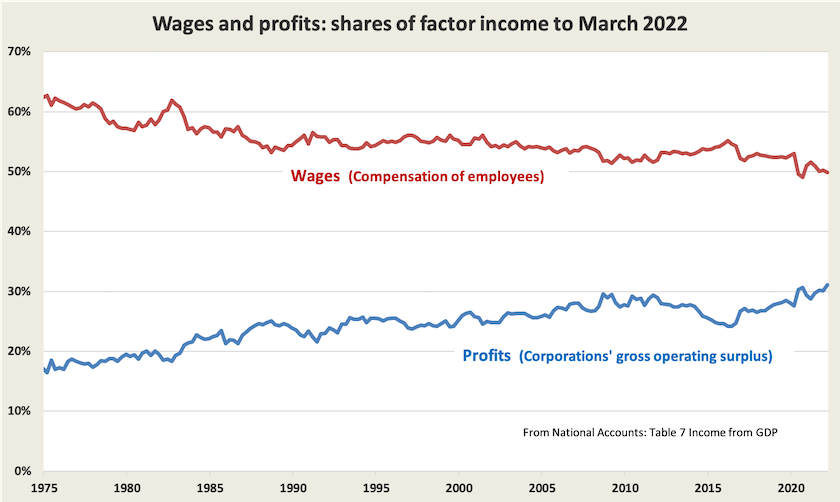

The answer lies in a statement in the national accounts that “the share of national income going to profits reached a record high of 31.1 percent”. A little digging into the accounts reveals that the share going to wages dipped to 49.8 percent, only the second time over the last 50 years that the wages share fell below 50.0 percent.[3] That uptick in profits and the corresponding fall in wages is evident in the graph below.

While a sustained growth in real wages cannot occur without a rise in labour productivity, there seems to be something askew in an economy that consistently delivers a rising share of income to the holders of capital while reducing the share of income going to those who supply their labour. The Albanese government surely has a strong justification for some re-distributive measures in the budget it will present in October, to relieve cost of living pressures on households whose main source of income is wages.

3. The other time was in the September quarter 2020, at the height of the pandemic, when the wages share fell to 49.1 percent.. ↩

Covid-19 and other annoying viruses

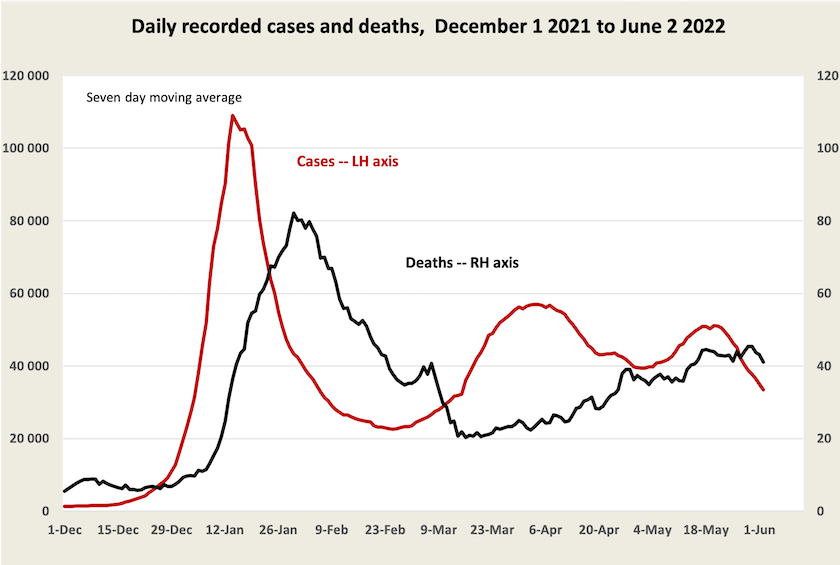

Public awareness of Covid-19 is finally rising again, just as the number of recorded cases keeps falling. This is possibly because of the inconvenience of closures on construction sites, staff shortages and so on. It is also possibly because the media are reporting on the high number of deaths – around 40 a day Australia-wide – and which are particularly high in Victoria which has experienced a steadier flow of cases than in other states. And the number of deaths is a reasonably good indicator of the load on our public hospitals. For every death resulting from Covid-19 there have been six people admitted to hospital, a substantial proportion of whom spend time in ICU.[4], [5]

On the ABC’s Breakfast program epidemiologist Tony Blakely reports on the present situation in Australia. He believes that in Australia we might have reached peak immunity a few weeks ago, and that immunity may now be waning as more time passes since people had their last vaccination: Winter to bring Covid uncertainty. His main message is that Covid-19 isn’t going away; at best it may slowly fade over coming years as natural immunity improves but until then it could keep on rising and falling, and he urges everyone to get their third (or fourth) vaccination. Although we achieved high levels of two-dose vaccination our takeup of third and fourth doses has been comparatively poor. (8 minutes).

Blakely also reminds us of the coming threat of influenza. After two years with hardly any influenza (thanks to Covid-19 public health measures), influenza cases are now rising faster than in recent pre-Covid years. Although many fewer people are presenting to hospital with influenza than with Covid-19 (about one tenth), most of these are young people, aged up to 20.

One for conspiracy theorists

Analysis by the ABC Story Lab finds that in the election highly vaccinated electorates swung towards Labor. The correlation is clear – the greater the proportion of the electorate with more than two doses, the greater has been the swing to Labor. The anti-vaxxers are right: there’s obviously something in those injections that turns us into socialists.

4. Ratio calculated from the New South Wales weekly epidemiological report, 21 May. ↩

5. For comprehensive data on recorded cases, deaths, hospitalizations and more, see the website maintained by Juliette O’Brien and her colleagues: Covid-19 in Australia. Data on vaccination is on the ABC’s vaccine tracker, maintained by Inga Ting and her colleagues. The Guardian’s data tracker has further select data, including reported infection rates in regions within states. ↩