What the election outcome revealed

It’s still the economy, but that hasn’t been to the Coalition’s advantage

In last week’s roundup I wrote that it would be some time before there is rigorous research on the election results, but the ABC’s Story Lab has produced a superb infographic, based on election returns and census data, revealing trends in voting patterns. It’s title is How the seeds of the 2022 election result were sown years ago, referring to the fact that in the 2019 election the Coalition was already losing significant support form voters concerned with climate change. The 2022 election is mainly a confirmation of that trend.

It goes on to present other findings including broad regional trends, and the shifting votes of those who believed “the economy” to be the most important issue, but this was not to the Coalition’s advantage: what worked in 2019 did not work in 2022.

There are messages about the two-party system in a finding that voters in richer and poorer electorates turned to independents and minor parties, while those in the middle tended to stick to the binary Labor/Coalition choice. And there are messages about “safe” seats. In short, it’s dangerous for anyone in either of the big parties to assume any seat is safe. Every seat is at risk.

One outcome of this election is that many of the seats the Coalition has hung on to are now highly vulnerable. It holds 21 of its 58 seats with a margin of less than five percent, compared with Labor holding only 12 of its 77 seats with such a small margin. The newly-elected Greens snd independents hold only small margins, but if past experience is any guide, independents tend to consolidate their position over time.

A look at the numbers from the Coalition’s side

The election wasn’t a “landslide” as some opinion polls had forecast. The party that received a majority of seats (77) did so with just 32.8 percent of the vote, a fall of 0.6 percent from its support in the 2019 election. That would be hard to explain to anyone unfamiliar with preferential voting. (Some of my American friends are puzzled, in spite of my lengthy explanations.)

While it wasn’t a landslide, for the Coalition it can be described as a “wipeout”. In terms of seats held by the opposition – 58 seats – it’s comparable to Labor’s 55 seats in 2013, or 49 seats in 1996. In fact it’s the worst ever result for the Coalition.[1]

For the Coalition the outlook is grim, and it’s even worse than those basic numbers suggest, for in past defeats it has been able to draw on its senators, with help from other senators on the far right, to thwart Labor’s plans. If Labor is to face difficulty in this Senate it will be from the Greens, not the Coalition. Also there is a possibility that this parliament will enact substantial political finance reform, which could work to the Coalition’s disadvantage: how would Palmer be able to get around legislation that limited campaign spending, for example?

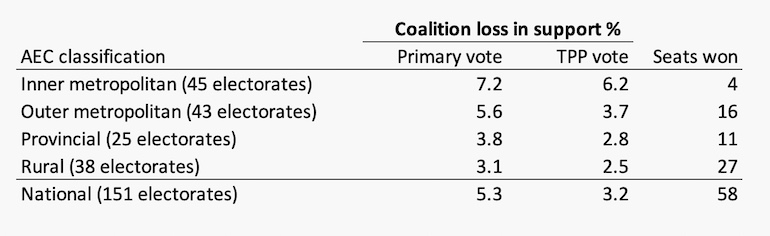

The table below shows where the Coalition lost support, confirming an established pattern – the further one gets away from a capital city CBD, the better have been the Coalition’s fortunes.[2]

Judging by Peter Dutton’s comments, the Coalition seems to be following the logic that it has little chance of winning back inner metropolitan electorates and that it already holds most seats in provincial and rural electorates (many of which are held by the National Party or the LNP), but it has opportunities in the outer metropolitan electorates where dwell the “forgotten people”.

The Coalition is probably heartened by a strong performance in five Victorian electorates (Calwell, Scullin, Gorton, La Trobe and Holt) on Melbourne’s outer fringes and in certain other electorates such as Spence on Adelaide’s far northern extremity. In all these electorates they would have been helped by preferences from One Nation and UAP voters: for example in Spence the combined ON + UAP vote was 17.6 percent and it was well above 10 percent in 16 other outer suburban seats.

One should be cautious before making any generalization about the Coalition doing well in the outer suburbs, however. It did well only in comparison with its losses elsewhere. In all but 4 of the 43 outer metropolitan electorates the primary vote swung against the Coalition, and even after preferences it picked up support in only 9 outer metropolitan electorates. The swings against the Coalition in Perth’s outer metropolitan electorates were just as savage as the swings it suffered in its inner metropolitan electorates, for example.

Also, to state what should be obvious, not all outer suburbs are the same. Is it merely coincidental that the best-performing regions for the Coalition and the UAP on Melbourne’s fringes are the same regions that saw so much strife and resentment during the Covid-19 lockdowns, where the UAP anti-vax message would have gone down well? Another impression from looking at these swings is that they seem to be in regions most badly affected by structural changes late last century and into this century. For example the shutdown of the car industry has left deep wounds in Adelaide’s northern suburbs, included in the Spence electorate. While the Coalition achieved one of the few swings in its favour in Spence (+0.9 percent TPP), it suffered a swing against it in Kingston (-4.4 percent TPP), a seat a similar distance from Adelaide on the opposite end of the city’s 75 km north-south sprawl.

Perhaps the Coalition (or more precisely the Liberal Party) bases its hope to win outer suburban seats on right-wing parties’ traditional political strategy of fooling people to vote against their economic interests. That’s essentially a Trumpist strategy, which has worked to the Republicans’ benefit in America, but it does not necessarily work here, because in America the disaffected have nowhere to go other than Democrat, Republican, or to abstain. Here they have other options as demonstrated by their support for ON and UAP, and there is no reason to believe that it’s only in well-heeled inner-city regions that people can mobilize around independents, as is demonstrated by Dai Le’s success in Fowler in western Sydney. There are lessons for both main parties in the Fowler story.

1. In the 1983 election that saw the Fraser government defeated the Coalition won only 50 seats, but that was in a 125-seat chamber. ↩

2. The TPP figure is based on traditional Labor/Coalition contests. It is not a particularly meaningful estimate for inner metropolitan electorates . ↩

The Dutton opposition

John Hewson’s regular Saturday Paper article last week was mainly about the Murdoch media’s blatant partisanship and the unprofessional performance of the media generally. He also had some advice for the Coalition: don’t react by swinging further to the right. He also commented on Dutton:

To even contemplate Peter Dutton as the new leader is insane, and could well spell the end of the Liberal-National Coalition. He has neither the skills nor the empathy for the job.

Perhaps Dutton can re-invent himself. Maybe he can reflect on his behaviour in government – his boycott of the apology to the Stolen Generation, his suggestion that rape victims on Nauru were “trying it on”, his offensive remarks about Lebanese Muslims, his claim that “white” Africans deserved special protection, his au-pair saga, his offensive comments about his political rival’s disability – and become the person fit to hold the highest office in the land. These transgressions are listed in a Canberra Times article by Finn McHugh: Peter Dutton: Who is the man set to lead the Liberal Party? (probably paywalled). Australian politics, and Australian public life generally, is replete with stories of redemption, and Dutton has already acknowledged some of his past mistakes.

One of the few occasions when politicians expose their values is their maiden speech, before they have been fully inducted into the parliamentary and party culture. He has a transcript on his website. It’s about how his beliefs have been shaped by his experiences as a police officer and in small business.

Both experiences tend to set people up for a right-wing mindset. Police see the worst of human behaviour in individual terms rather than in terms of the societal reasons for bad behaviour. The general culture of small business is about individual achievement. (Police rarely acknowledge that they are on the public payroll, and small businesspeople rarely acknowledge their dependence on publicly-financed infrastructure and the regulatory power of the state in enforcing fair trading provisions.)

ABC journalist Peta Fuller has an article Key moments from Peter Dutton's first press conference as Liberal leader, drawing a few inferences about his future direction.

But is there too much emphasis on Dutton as “the leader”? Political parties are savagely majoritarian in their own organizatons – ask John Gorton, Kevin Rudd, Tony Abbott, Malcolm Turnbull. Dutton is beholden to what is left of the parliamentary Liberal Party, and to whatever threats the National Party may wield, now in a relatively much stronger position than it was previously. Also there is more to any party than its parliamentary wing. The parliamentary and local branches of the Liberal Party are often in conflict, and in some branches there is evidence of branch-stacking by so-called “Christian fundamentalists”. It used to be the left that suffered ideological divisions within its ranks; now it’s the right’s turn.

The other burden carried by Dutton is his harsh treatment of refugees, brought explicitly to our attention by the deliberate cruelty inflicted on the Biloela family, and experienced by thousands of others who have fled persecution. Most moral codes, religious-based or humanist-based, condemn deliberate cruelty inflicted on innocent people in order to achieve policy ends, even if those ends (in this case border security) are legitimate.

Dutton is not alone in this moral shortcoming. His predecessors in the Liberal Party from Howard onwards, and those in the Labor Party who have gone along with these policies, all bear responsibility, as do all of us who have been content to sweep the issue under the carpet. It’s a moral failure that has left a deep stain on our political culture. Only the Greens and some independents have had the courage to speak out.

Border protection is not easy, and a morally justifiable policy is difficult to craft. That’s a challenge for both our main parties.

The Coalition’s long-term demise

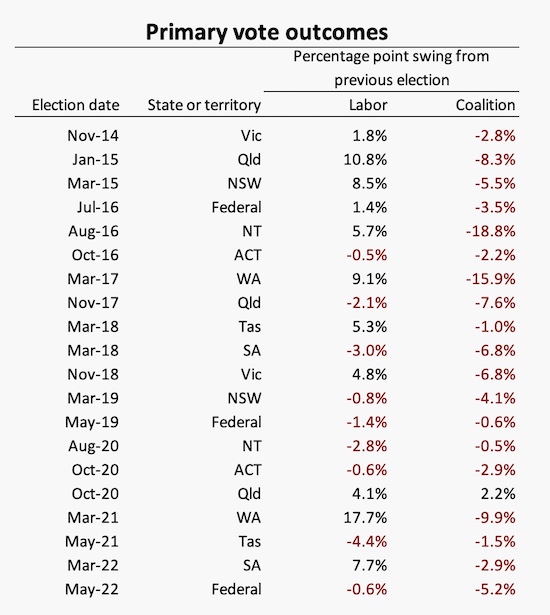

In last week’s roundup I promised that this week I would update the table of the Coalition’s fortunes in state and federal elections. Another line has been added to the table: this is now the 19th of those elections in which the Coalition’s primary vote has gone backward. (Labor, by contrast, has had more patchy performance.)

Surely someone in the bowels of the Liberal Party and National Party organizations would have a similar table, which should be leading the Coalition to be considering seriously where they are heading, but there is no evidence that they are reacting to the clear message in these figures.

Because of the merger of the Liberals and Nationals in Queensland, and the absence in this election of contests in which both Liberals and Nationals were campaigning, it is hard to separate the Liberals’ from the Nationals’ performance, but it does appear that the Liberals have done worse than the Nationals. That’s certainly the message from the National Party who kept all their ten seats and enjoyed an improved TPP vote in four of them.

But maybe that’s because the Nationals generally did not face challenges from independents. In two electorates with strong independents – Cowper along the New South Wales North Coast, and Nicholls between Melbourne and the Murray River – there were strong swings against the Nationals, and both of these seats, once “safe” National strongholds, are now marginal.

An explanation for the demise – counting the ways

On last weekend’s Saturday Extra Geraldine Doogue interviewed Greg Barns and Judith Brett on The Liberal Party’s move to the right – a discussion of the many ways in which the Liberal Party has lost its appeal to the electorate. They hardly mentioned Scott Morrison. That’s because they trace the party’s troubles back decades, starting with the election of John Howard in 1996. In the 16-minute session they covered many factors contributing to the party’s demise: its deliberate use of divisive language (“battlers” vs “élites”), administrative and policy incompetence (Brett suggests that the Morrison government was even more incompetent than the McMahon government), the influence of career politicians, the jarring contrast between the “liberal” brand name and the party’s hard conservatism, the way it courted movements on the far-right and “evangelical Christians”, and its obsession to differentiate itself from Labor (even when Labor was promoting policies that should be attractive to centre-right parties).

They mentioned Barns’s 2019 book Rise of the right: the war on Australia's liberal values and Brett’s 2009 book Australian Liberals and the moral middle class. Lending credence to Barns’s claim that the party’s drift goes back a long way they also referred to his book What’s wrong with the Liberal Party?, published in 2003. One cannot attribute his comments to the wisdom of hindsight.