The election

Trends in plain sight

There is a story that when Henry Kissinger asked Zhou Enlai about his interpretation of the consequences of the French Revolution, Zhou’s reply was that it was “too early to tell”.[1] So it is for an election only 6 days old, where there is still the possibility that the governing party will be short of a majority in the House of Representatives, and where the Senate result may not be known even by this time next week.

The main parties have been losing support for a long time

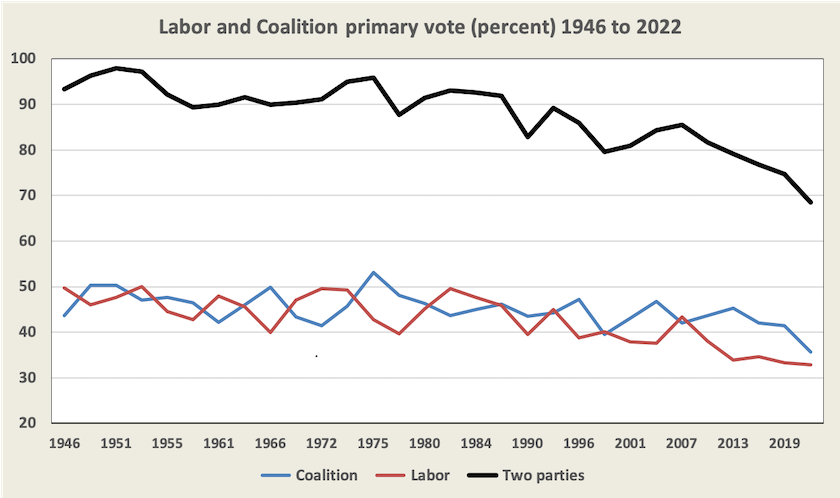

Perhaps the greatest surprise is that so many people are surprised by the outcome. At federal elections the two main parties have been losing support for the last 75 years, particularly since Malcolm Fraser’s landslide win in 1975.

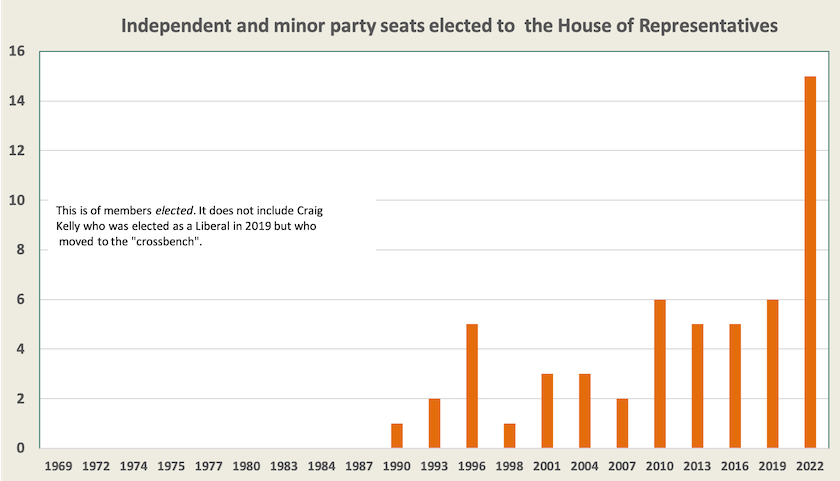

As support for the main parties falls, so does their parliamentary position. Over the last 30 years there has been a been a rise in the number of members of the House of Representatives who do not hail from the two main party groupings.

This latter development has taken longer to show up than the decline in the main parties’ vote, because in any electorate an independent or third-party candidate has to secure enough support to trigger a preference distribution before he or she has any chance of being elected. There always has to be a preference distribution when the lead candidate achieves less than 50 percent of the primary vote, but preferences tend to help an independent or a candidate from a small party win a seat only when they come second and the lead candidate’s primary vote dips below about 40 percent. That takes time to happen but when it does, over many electorates, the number of seats won by independents and small parties grows quickly. Even if Labor achieves a bare majority this time, it could be the last majority government for a long time.

The Coalition’s long-term decline

A related trend, that was clear before the election, is an apparently irreversible decline in the Coalition’s primary vote. In this election the Coalition’s primary vote (36 percent) is higher than Labor’s (33 percent), but its decline in support since 2019 (5.3 percent) has been far worse than Labor’s (0.6 percent).

As pointed out in the Roundup of March 26, in 18 of the 19 state and federal elections that have been held since 2014, the Coalition has lost support.[2] This election makes it 19 out of 20. I will present the updated table next week, when we have firmer figures from the AEC. In those 20 elections Labor’s support, while being on a downward trend, has had its ups and downs, but for the Coalition it has been 95 percent down.

The National Party lost support but kept its seats

In this election most focus has been on the success of high-profile independents and Greens in seats with high-income, well-educated voters, which means the Liberal Party has taken almost all, or even all, of the losses, but the National Party has shared in the swing. For example in Nicholls, an electorate that stretches from the Murray River south to cooee distance from Melbourne’s northern suburbs, and that abuts Indi (a rural seat where an independent has now won for the fourth consecutive election), a strong independent won 26 percent of the vote, reducing the National Party’s margin from 20 percent to 5 percent. The National Party may be crowing about the way it has hung on to its seats, in comparison to the hapless Liberals, but that can be attributed to their having had large buffers. Many of their once “safe” seats are marginal.

Independents are hard to dislodge

Another observation is that independents, once elected, seem to go on being re-elected. For example Clark, the electorate incorporating most of Hobart, was solid Labor territory for 23 years until 2010, when Andrew Wilkie won it for the first time: four elections later he is on 70 percent after preferences. In Indi there has been a transition from one independent to another. The electors of Mayo, a once “secure” Liberal Party seat in the Adelaide Hills, have elected an independent for the fourth time. In North Queensland Bob Katter seems to have become a permanent part of the political landscape.

Coal was not a loser for Labor

Ever the clear communicator, Casey Briggs has presented five graphs that tell the story of the election (or at least parts that the mainstream media may have missed). He draws attention to something that didn’t happen – the expected swing against Labor in coal country. The One Nation vote in coal country seats collapsed. Labor held the two main New South Wales coal seats, Hunter and Paterson, one with a small positive swing, the other with a small negative swing, and enjoyed big swings in its favour in the Queensland seats of Flynn and Hinkler, reducing the LNP’s margin in the former seat to just 2.1 percent.

The populist right did well in disadvantaged regions, but its support may have plateaued

In this election One Nation and Palmer’s UAP secured 9.0 percent of the vote between them. Their combined support was above 12 percent in 30 electorates, 18 of which are in Queensland. Most of these electorates, in Queensland and in other places, are on the far-flung outskirts of our big cities. At first sight these parties seem to have done well compared with 2019, but they have contested more seats than in 2019. Writing in CrikeyCam Wilson points out that in this election One Nation has contested 149 seats, compared with 59 seats in 2019. In that context its national gain from 3.1 to 4.9 percent of the vote doesn’t look so impressive, and it probably represents a decline per seat contested: Is the 2022 election result the beginning of the end for Pauline Hanson’s One Nation?.

More to come as people analyse the figures

Anyone wanting to dig into the results, or to follow the count in the last four doubtful seats as postal votes trickle in, can go to Antony Green’s ABC website (it’s a corker!), or to the less colourful Australian Electorate Commission website.

In time there will be substantial analysis of the outcome by bodies such as ANU’s Centre for Social Research and Methods – swings by region, age, income, education and other variables.

But first the AEC has to finish counting the votes.

1. Maybe there was some misinterpretation, but the general point is that the consequences of political events are rarely clear at first sight.↩

2. And in the election it gained primary vote it actually lost office. ↩

Speculations and other comments

Is this the end of the two-party system?

Antony Green has drawn our attention to some not-so obvious aspects of the election: The federal election result shows a shift in Australian politics.

He believes that in spite of the poor showing of both main parties and the rise of a powerful group of independents, the two-party system will endure. He also believes that “one or other of the traditional parties will continue to form government”.

They’re both strong assumptions when there is evidence that both the main parties – first Labor and more recently the Coalition – have lost the support of their traditional bases.

While he sees much of the pre-election commentary as pure rubbish, he sees two significant developments. To quote:

The main takeaway, however, is that there has been a substantial rejection of the Coalition government that has not necessarily translated to an embrace of the Labor government.

But it has definitely translated into new members elected who want something done about climate change and a corruption commission. So it's a definite shift in policy from the members elected.

One could add the observation, from election-night viewing, that there were a lot of young people and women surrounding the successful independent and Greens candidates, in contrast with the Labor, National and Liberal gatherings.

A slow merge, not a turn

A move to the left?

Writing in The Conversation, Frank Bongiorno asks Did Australia just make a move to the left?

In a guarded way he answers that question in the affirmative. He acknowledges the success of independents, but he also reminds us that in many Coalition electorates where there were not strong independents Labor has taken votes from the Coalition. In this regard, behind the much-noted teal/green revolution, there was also a traditional Labor-Coalition contest, in which Labor performed rather well.

Bongiorno suggests that it’s more informative to see the election in terms of a “progressive”/“conservative” contest rather than a traditional “left”/“right” framework. He writes:

Climate and energy policy, more than any other issue, now defines what it is to be “conservative” and “progressive” in Australia. This is the handiwork of a succession of powerful conservative politicians who saw political advantage in this framing and enjoyed their parties’ relationship with the fossil fuel industry.

Those same conservative politicians may now “behold their achievement”, as they face a stretch in the political wilderness.

The Morrison government and the media

Tim Dunlop has drawn on Arthur Miller to title one of his posts Death of a Salesman?. It’s an assessment of Scott Morrison’s unsuitability to hold high office in a democracy, and of “how corrupt and corrupting our failed political media are”. Morrison has been guided by “a philosophy of bullies and the self-serving.” Of that philosophy he writes:

It is not just profoundly anti-democratic, it is anti-Christian, something I only mention because he so often hides behind the faux Christianity of his prosperity-gospel Pentecostalism.

He goes on to write:

The awfulness of the Morrison Government cannot be separated from the supine support it receives from most of the media, but at least we can vote the government out … [The media] will continue to eat away at the foundations of our democracy, putting their own interests ahead of the greater good, and failing to properly distinguish between truth and lie.

David Hardaker, writing in Crikey, writes specifically about the Murdoch media’s having thrown everything it had at discrediting the government’s opponents. It had the usual anti-Labor bias, and in this election directed almost the same barrage of hatred and lies against independents: Just how badly did News Corp’s attacks fail? We count the ways.

Fortunately, however, “voters paid no heed to warnings that Australia would be plunged into chaos if independents were elected, and ignored the endless attacks on ‘red’ Anthony Albanese”.

How did the Liberal Party get to this point?

Mark Kenny is one of many to write about the Liberal party’s woes. His Conversation article Morrison’s ‘great electoral bungle’ leaves the Liberals decimated and heading in the wrong direction sees the party’s inglorious defeat not only in its campaign idiocy (what was on Morrison’s mind when he endorsed Katherine Deeves for the Warringah contest?), but also in earlier policy stances, particularly its rejection of the National Energy Guarantee championed by Frydenberg and Turnbull. He goes back to Tony Abbott’s ideological zealotry, pointing out that “courting the applause of extreme media voices is a formula for narrowing a party’s electoral reach”.

In all, he is writing about an organization that has no record of learning from its past mistakes.

David Marr, writing in The Guardian, goes back even further: Stoking fear and hatred held the Coalition in power – finally Australia had enough.

The great political hiatus of the last decade was only possible while decent conservatives held their breath and kept voting Liberal. All the way back to Menzies, the party has snubbed progressives in its own ranks knowing that, come what may, the great class divide in Australia would keep them voting Liberal.

Until the time came, last Saturday, when it didn’t.

Both Kenny and Marr attribute the Liberal Party’s woeful performance to their structural, organizational and cultural problems. That’s an important emphasis, for so egregious was Morrison’s behaviour that it is tempting to attribute to him all the failures of the just-defeated government.

As much as most Australians may feel relief at his departure from office, it would be unwise to make him the scapegoat for those failures. In a democracy we bear collective responsibility for the behaviour of the governments we elect. We cannot simply blame party “leaders”, such as Howard, Abbott and Morrison, because we have made the collective choice to elect them. We all have to share the obligation to strengthen the formal and informal institutions of democracy to ensure that such people do not rise to positions of authority again. For every one we banish, there are others ready to take their place.

Where should the Liberals now head?

The Liberals’ cheer squad in the Murdoch media have no doubt where the Liberal Party should go, writes Amanda Meade in The Guardian. In shock and anger over Liberal defeat, Sky News commentators urge party to shift right. She describes the distress Paul Murray, Rowan Dean, Peta Credlin, Michael Kroger and other Sky journalists and regular guests are enduring, particularly when they had been convinced that the opinion polls pointing to a Labor win were all wrong.

Andrew Bolt, however, sees some good in the outcome:

Who’d vote for such a mewling pack of self-haters with so little self-respect that they won’t even sack a party traitor like Malcolm Turnbull? Thank God this election wipe-out has taken out many of their worst grovellers.

That the Liberal Party should make a move to the “right” is quite plausible. When institutions suffer shock they often redouble their efforts to do what they were doing before: it’s a way of directing the energy that comes from anger and frustration.

Both the party’s organizational base and its parliamentarians are out of touch with the Australian community – more so with the loss of the so-called “moderates” from its parliamentary ranks. So a move further to the populist right, leading perhaps to a merger with One Nation could be an attractive default option for its remaining members, egged on by the Murdoch media, and inspired by the vision of a Trump-style party down under.Stories of election fraud are already starting to circulate, providing an appealing narrative for those who feel they have been left behind by the elites.

Or the Liberal Party could tear itself apart even further, vacating the moderate right space for a new party to emerge: this is what happened in 1944 when the United Australia Party collapsed and Menzies helped bring the Liberal Party into existence.

The most difficult option is reform. It may be too old, too tired, too incapable of looking at itself as others see it, too disinclined to understand the streaks of luck that have delivered it victory in the past, too wedded to a coalition with the National Party, and too much inclined to attribute its losses to a failure in presentation rather than as a failure in its assumptions about the electorate and its platform.

Whatever our own political leanings, anyone concerned for the health of democracy in our country should hope to see a strong centre-right party once again on the political landscape. We need a party that can engage with the community on questions of public policy and on political choices, rather than on fuelling division, engaging in culture wars, and promoting fear and hatred.

Labor learns that politics is local

The western Sydney electorate Fowler has been a Labor stronghold since the seat was created in 1984. It is centred on Cabramatta, which probably has Australia’s highest concentration of Vietnamese immigrants and their descendants, many of whom came to Australia during the Vietnam War. The local branch of the party, and the retiring Labor member, had lined up Tu Le, a lawyer from a local Vietnamese family, to nominate for the seat – a preselection she would almost certainly have won.

But the officials from central office had other plans. In a factional deal, involving the infamous New South Wales “right” faction, Senator Kristina Keneally had lost her spot on the party’s Senate ticket. The party heavies figured that a move to the House of Representatives, bumping someone out of a “safe” seat, would ensure that Keneally would be elected and probably be in the ministry. As a former premier of New South Wales she would be an asset on the front bench of a Labor administration.

But it was not to work out that way. Dai Le, former deputy mayor of Fairfield (which includes Cabramatta) and a former ABC journalist, nominated for the seat. She is one of the Vietnamese boat people who came to Australia with her mother in 1979, after spending years in refugee camps. She had been a nominated Liberal Party candidate in state elections, but fell out with the party over issues to do with local government elections.

In last Saturday’s election she secured 31 percent of the vote, and narrowly won the seat on preferences. Labor suffered a 19 percent swing against it. The ABC has a short article showing how the polling booths that were strongly Labor in 2019 switched to Dai Le in 2020. The ABC also has a 6 minute video on her campaign and victory. She has stood as an independent, but respectfully distinguishes herself from the “teal” independents who represent very prosperous electorates.She is a local member in a seat where local issues matter, and immigrants are unlikely to have established class-based loyalty to a particular party.

One lesson for the Labor Party bosses is to respect local branches. In that regard it has been just as dumb as the Liberal Party bosses who interfered in Sydney pre-selections, most notably in Warringah.

The other lesson relating to politicians generally is to recognize that our big cities have distinct regions within them. Over the last 20 years or so politicians and journalists have been using the word “region” to refer to any part of Australia that isn’t within our capital cities, as if those cities, where two-thirds of Australians live, are homogeneous undifferentiated blobs.

It hasn’t alsways been so: Tom Uren, Minister for Urban and Regional Development in the Whitlam government, recognized the importance of a policy approach that recognized and respected distinct regions within our big cities. If the Albanese government is to re-connect with people in outer-suburban regions, who have been wooed by far-right populist parties, they need to realize that all Australians live in regions.

Opinion polls – and the winner is …

The inaccuracy of opinion polls was a huge issue in the 2019 election. How did they do this time?

The graph below shows the predictions of opinion polls published in the final week of the campaign, including the Newspoll estimate published in the evening before the election.[3]

Notably Newspoll significantly overstated Labor’s support, and Essential understated support for minority parties.

The final Newspoll had Labor leading on a two-party-preferred basis 53:47. Those TPP figures are becoming less meaningful, however, in a contest where preferences don’t all come back to main parties, but to Greens and independents. Willian Bowe has done a TPP estimate of the outcome based on Labor-Coalition contests, and calculates the outcome at 51.8:48.2 in Labor’s favour. His Bludger Track also shows some tightening in the contest from around March. Betting markets, by contrast, tended to shorten the odds for a Labor victory as the election approached.

As students of voting know, when there are more than two candidates it becomes very difficult to determine voters’ preferences (impossible in fact as Kenneth Arrow demonstrated in his impossibility theorem). Barring the unlikely possibility that we will revert to a simple two-party contest, even the best pollsters with large samples are going to find it more and more difficult to predict election outcomes in the future.

3. Essential and Ipsos also had unallocated “undecided” categories, of 7 percent and 5 percent respectively. Ipsos included One Nation and UAP in “other” . ↩