Neglected issues

Economic reform

There is a great deal of chatter about “economics” in the campaign, but mainly in terms of claims and counter-claims about economic indicators, gotchas, and demands for Albanese to guarantee that under a Labor government taxes will never rise, real wages will always rise, and that the budget deficits will always be lower than they would be under a Coalition government.

The real economic challenge relates to our poor productivity, which relates in turn to our sclerotic economic structure. Only if we can raise productivity through structural reform will we be able to achieve sustained higher private incomes and better public services.

On Late Night Live, regular commentator Satyajit Das, in a 15-minute interview, outlines our structural weaknesses: Australia’s economic choices: houses and holes. He lists seven related structural weaknesses of the Australian economy:

- Exposure to the fluctuations of commodity prices – affecting private incomes, corporate profits and public revenue.

- Dependence on three commodities, two of which (thermal coal and gas) do not have a future.

- Dependence on China, which has other sources of raw materials.

- Dependence on exploiting finite stocks of raw materials. Perhaps our mining sector might wisely shift from fossil fuels to minerals in demand in a low-carbon future, but these are still a depleting resource.

- Foreign ownership of our extractive industries: whatever benefits we enjoy are residual after foreign owners take their cut.

- Our use of the returns from these depleting resources for consumption rather than re-investment, for example in a sovereign wealth fund.

- Our over-commitment to housing at the expense of assets that can generate income in the long term, and the related problems of high household debt and the wealth illusion of high house prices.

In the campaign the Coalition has completely disregarded economic reform, essentially arguing that because all is in good shape under the Coalition’s self-evident competence in economic management, there is no need for reform. They see no need to depart from their priorities of low wages and small government.

Labor acknowledges the need to raise productivity, and has policy proposals to do with child care (increasing opportunities for women to engage in high-productivity paid employment), a slightly more rapid transition to de-carbonization than is offered by the Coalition, investment in skills and education, and establishment of a National Reconstruction Fund. All are in the economic direction of improving productivity, but they are modest in scale compared with the economic reform program of the Hawke-Keating government.

The Greens, with their advocacy for rapid de-carbonization, have the most ambitious policies for structural adjustment, but they do not have the practical problem of promoting a political platform that appeals to 51 percent of voters.

Satyajit Das is author of Fortune’s Fool: Australia’s Choices, one of Monash University Publishing’s In the national interest series. One may argue that there is nothing particularly new in his work. His exposition of our structural weaknesses is very similar to the explanation and analysis in the Centre for Policy Development’s 2013 work Pushing our luck. That in turn drew on Donald Horne’s 1964 work The lucky country. But the message has to be repeated and renewed, because it is so easy for vested interests to block structural change. In election after election the Coalition has used fear of structural change, and lies about its consequences, as the basis of its generally successful political strategy.

Health care

One of the Coalition government’s last pre-election acts was to reduce the co-payment on PBS pharmaceuticals from $42.50 to $32.50. Not to be outdone, Labor has promised to reduce it to $30.00.

To its credit, Labor promises a little more than a reduction in the consumer cost of PBS pharmaceuticals. Its other proposals, described on Labor’s website, include a program to build 50 urgent care clinics, designed to reduce pressure on over-stretched emergency wards, but it’s only a small contribution – $135 million over 4 years – towards solving a very large problem. Labor also proposes some improvement to rural health services.

But is this all, from the party that fought a double dissolution election in 1974 to introduce universal public insurance?

Labor’s long record in health reform

Surely there’s more to come

Many are hoping that Labor can re-kindle the fire in its belly about health care. In times past Labor fought hard to establish universal health care. Even though the subsequent Coalition government demolished the Whitlam government’s Medibank, in 1983 the Hawke government re-established universal publicly-funded health insurance as Medicare.

Medicare was a work in progress. For example, although there was pressure to include dental services in Medicare, this was not seen as a priority but it was a long-term policy goal. Forty years on, however, it is still shoved over the horizon.

Similarly private health insurance, instead of being abolished, was allowed to fade out slowly: over the 13 years of the Hawke-Keating government private health insurance cover fell from 50 per cent to 30 per cent of the population. That was transitional: Labor’s original aspiration was that Medicare would be so reliable that no one would ever want to hold private insurance.

The subsequent Coalition government re-established subsidies for private health insurance, entrenching the public-private division. The Rudd-Gillard government had a go at health reform, but it bound itself from the start by promising to protect private health insurance. It had lost enthusiasm for reform. Like previous and subsequent Coalition governments, the Rudd-Gillard government did no more than to muddle through with piece-meal interventions to address specific problems, while avoiding the sort of fundamental reform that established Medibank and Medicare.

Labor’s present modest proposals

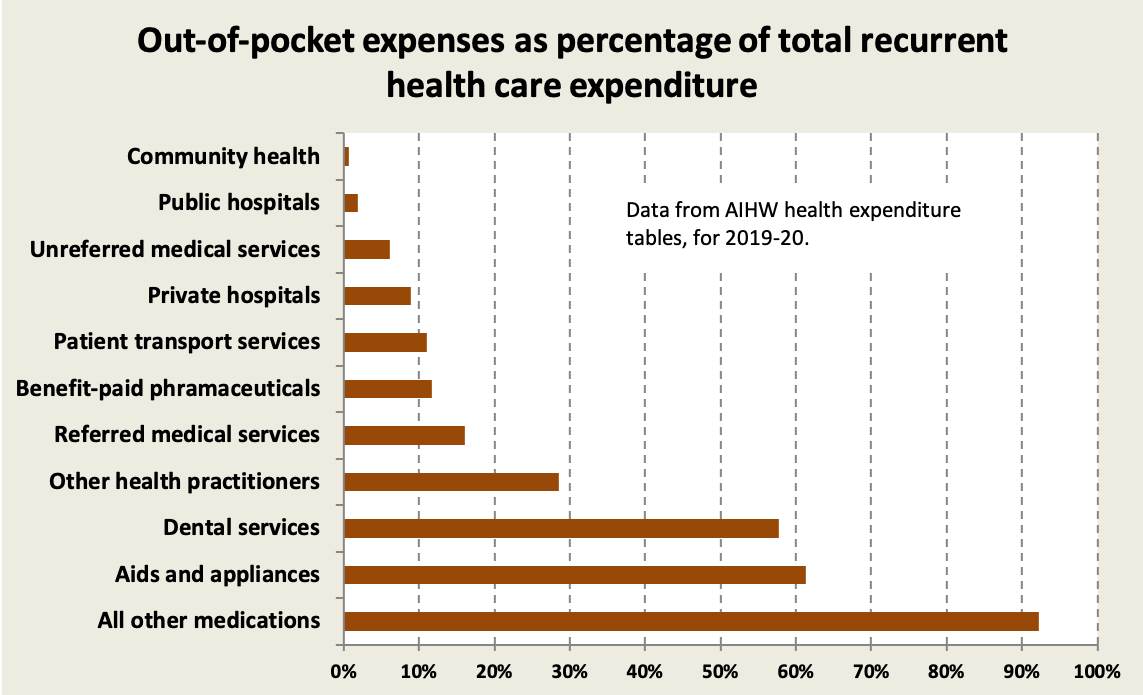

In the election campaign Labor is far less ambitious than the Whitlam and Hawke governments were. Making prescription pharmaceuticals more affordable is a useful move, but should it be a priority over other possible changes? In terms of the burden on consumers, the PBS already has reasonably strong consumer protection, with its safety nets and strict price control. By contrast consumers are likely to face high and uncapped out-of-pocket outlays for specialist fees, dental services, aids and appliances and non-prescription pharmaceuticals, as shown in the chart below.

The annual consumer payment for prescription pharmaceuticals – the PBS co-payment – is $1.5 billion. By contrast consumers pay $5.5 billion for dental services from their own pockets, and $13.7 billion for aids, appliances and non-prescription pharmaceuticals.

Another problem is that having reached a low point of 43.6 percent in mid-2020, private insurance cover is now rising again – to 44.9 percent at the end of 2021. Private health insurance, as it operates in Australia, takes resources out of public hospitals, encourages queue-jumping, drives up the cost of health care, is inequitable, and is administratively expensive. A reforming Labor government would arrest this resurgence in health insurance by ensuring that everyone has confidence in Medicare.

Labor is still muddling through rather than completing the hard task of embedding Medicare.

Calls on Labor to be bolder

Many people have been calling on both the major parties to do more on health care. Unsurprisingly the Australian Dental Association has made a pitch for more government support for dentistry.

Another call has been made by Clare Skinner, president of the Australasian College for Emergency Medicine, speaking on the ABC’s Breakfast program: Hospitals facing “national emergency”. The specific context was the extra load still resulting from Covid-19, including the backlog of cases that were delayed when the pandemic was raging. There has been huge demand on hospital emergency departments ever since the pandemic first appeared, and the situation is worsened by the resignation of overworked and weary staff.

Skinner’s general message was that, as usual, both major parties are offering only piece-meal changes, when what is needed is “deep structural reform” in the delivery of health care. It is too fragmented with divisions of responsibilities between the Commonwealth and the states, and between the private and public sectors. “It’s fair to say we don’t really have a health system: we have a series of health services which are attempting to work together. We need to integrate those.”

What health reform could look like

Integration would involve bringing hospital and ambulatory services, particularly GPs, under one system of funding, bringing private hospitals into the same funding system as public hospitals (as was done at the height of the pandemic), rationalizing co-payments so that consumers are not left with open-ended health care costs, removing subsidies and incentives for private health insurance, controlling specialists’ fees through regulation or competition, subjecting pharmacies to more competition, making better use of all health professionals, and improving the sector’s use of information technology.

In health care there is so much duplication, burnout and resignation of staff, administrative inefficiency, unjustified profit, and unnecessary demarcation between professions, that a great deal of reform could be achieved without increasing public expenditure or shifting costs on to consumers. Providing an affordable, accessible health care system, without anybody feeling a need to hold private insurance, is a way Labor could address cost-of-living without contributing to inflation.

Immigration

Perhaps in a campaign in which Australians are considering weighty issues such as the rights of transgender people in sport, and the capacity of the opposition leader to recite NDIS policy details, it’s understandable that minor issues like immigration command little attention.

The prevailing narrative about immigration is that restrictions on immigration have been responsible for our low unemployment rate (I forget the precise figure), and that if we lower the bar for entry to Australia we can fill all those vacant hospitality, horticultural and other low-skill positions.

Will Mackey, Brendan Coates and Henry Sherrell of the Grattan Institute take issue with both aspects of that conventional wisdom, in their work “Migrants in the Australian workforce: a guidebook for policy makers”, summarized in a short article Don’t fiddle with migration policy to try to fix short-term labour shortages. Our low unemployment rate is almost entirely due to the combination of low interest rates and stimulatory fiscal policies. Only in some low-skill-low-pay industries are border closures responsible for labour shortages

They urge whatever government we elect to resist the temptation to make it easier for low-skill immigrants to fill temporary labour shortages. “As we have seen in agriculture and hospitality sectors, once an industry relies on low-wage labour, it is hard to wind the clock back”.

Their work was published well before Albanese made his statement supporting an increase in the minimum wage to keep up with inflation.