The campaign, if anyone’s listening

Wages – can we afford free beer for all the workers?

Wages have dominated campaigning in the past week. Morrison claims that an increase in the minimum wage to compensate for inflation, currently measured at 5.1 percent, would set off an inflationary spiral, similar to that which occurred in the 1970s.

The politics are simple: Labor will try to prevent a fall in real wages; the Coalition wants real wages to fall. Labor’s message that suppressing wages has long been a cornerstone of the Coalition’s economic policy is reinforced. Because women are over-represented in minimum-pay occupations, gender politics also come into play.

The pampered small-business sector has joined the chorus of opposition to a 5.1 percent wage rise, claiming that many small businesses would struggle to absorb the cost of higher wages, and that a requirement to pay higher wages would squeeze business profits.

That protest is disingenuous, however. Higher wages would squeeze profits and threaten firms’ viability only if they could not pass on wage rises as higher prices. Because most small businesses operate in the domestic economy, they probably have capacity to pass on wage rises, which means the real issue is about price rises. Also small business spokespeople tend to forget the basic economics of capitalism: wages, particularly wages of those on low incomes who spend every dollar they earn, recycle to businesses as revenue.

A wage rise need not be inflationary. If it is directed to lowest-paid workers it would register as a rise in the CPI, but would not contribute to the general problem of inflation. The distinction is important, because it’s about the difference between a once-off price rise, and a positive-feedback loop of ongoing inflation.[1] A wage rise at the bottom of the pay scale would be a change in income distribution as the well-off pay more for their coffee, holiday accommodation and avocadoes.

In reality the economic problem is about wage stagnation rather than inflation. Andrew Stewart, Jim Stanford and Tess Hardy of the Centre for Future Work analyse the causes of wage stagnation in a report “The wages crisis re-visited”, which lists nine reasons why wages are not rising in the way conventional economic models predict. These include the declining strength of collective bargaining mechanisms, the influence of statutory wage-fixing arrangements, wage freezes in the public sector, sham contracting, and wage theft. The report is linked from the centre’s press release: Wages crisis will continue without active wage-boosting policies.

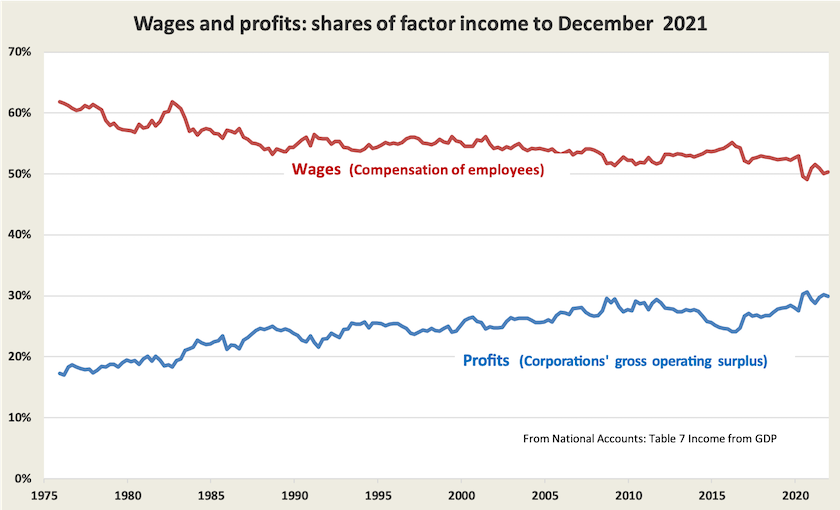

There is no magic pudding, however. In the long run we cannot have sustained wage growth unless our productivity improves. In a nine-minute interview on the ABC’s PM economist Richard Holden explains the conventional economics of the relationship between wages and productivity. But in the medium term there is a simple way to improve wages without stimulating inflation. The graph below is self-explanatory.

1. Inflation is defined as a general decrease in the purchasing power of money, not a once-off adjustment in relative prices. The CPI is simply a commonly-used indicator of inflation but it is more correctly an indicator of the shifting prices of a basket of consumer goods. ↩

That unedifying debate on commercial media

Because the second debate was on commercial media at Morrison’s insistence, I cannot provide a link to the session. There are snippets online, but they are selective and out of context. Even if the whole session were available, people would probably find it more edifying to spend an hour watching professional wrestling or boxing, where there are formal rules and referees can exercise their authority.

In a Conversation article – A shouty, unedifying spectacle and a narrow win for Albanese: 3 experts assess the second election debate – three academics express their views of the debate.

Gregory Melleuish of the University of Wollongong finds that Morrison appeared to be frustrated by the format of the debate, because “it restrained his natural marketing style and this lured him into being more aggressive than he might have wished to be”.

Sana Nakata of the University of Melbourne is surprised that Albanese didn’t pitch more towards younger people (perhaps they have given up on television), and she notes the lack of any question on First Nations policy.

Joshua Black of the ANU observed the non-verbal aspects, suggesting that one should watch the debate with the sound off. He writes:

Albanese looked earnest but frustrated, determined to show strength and spirit but clearly exasperated at repeated efforts to skewer him. Morrison oscillated between a smug placidity and high-octane dominance of the space, smirking at some moments and gesticulating wildly at others.

He also notes the impression conveyed by two men shouting at each other while disregarding the young woman moderator.

All three judge the debate to be a narrow win for Albanese.

Perhaps that finding could be re-framed as a worse loss for the Coalition than for Labor, because if there is any “winner” from the way this campaign has been conducted, with its misrepresentations, lies, hypocrisy, hysterical claims about the perils of a change of government, gotchas, diversions into trivia, and avoidance of serious issues, it must be the well-organized independents who have been focussing on matters of concern to Australian voters.

Journalists’ assault on democracy and on their own profession

As News Corp goes “rogue” on election coverage, what price will Australian democracy pay? asks Denis Muller, writing in The Conversation.

He illustrates the hyper-partisanship of the Murdoch media – The Telegraph, The Herald-Sun and Sky – in the campaign, noting that it is not only anti-Labor, but, as its hysterical attacks on “teal” independents demonstrates, that it is essentially a mouthpiece for the Coalition. Readers and viewers of those media have been treated to “propaganda, distortions, crudity and pro-Liberal apologia”.

Of particular concern to Muller is the way Murdoch newspapers are so readily available (notice how they seem to be the only choice in country towns), and how Sky after dark has made its way into non-metropolitan regions. He writes:

This abandonment of a fundamental news media obligation to truth-telling is by definition harmful to a democratic society. Not only does it rob the population of a bedrock of reliable news; it debases the entire discourse. It is also a fraud on the people by misrepresenting propaganda as news.

The Guardian’s Malcolm Farr calls out journalists for their arrogance and rudeness. He notes as an example the behaviour of a journalist from Nine TV in ambushing Albanese with a question about the six points of Labor’s NDIS policy. “The reporter clearly wanted to be the star of that press conference, not the alternative prime minister”, he writes: The gotcha question is all about reporters doing a star turn. It’s rudeness journalism.

David Hardaker, writing in Crikey, goes beyond issues of partisanship and rudeness. He is critical of the way journalists are making stories out of their own behaviour in this campaign. These stories have crowded out serious issues at stake in the election. Little wonder then that journalists have lost the public’s trust: Journalism is going to have to save itself — because the way it’s going, frankly it’s done for. Through their behaviour, journalists have played a significant role in weakening trust in government and in the institutions of democracy. He concludes with four rules of political journalism, the last of which is:

… do the hard work of journalism — find facts and prosecute a case. Don’t imagine that gotcha questions are Journalism At Its Best. You are further alienating public trust and helping charlatans with the gift of the gab into positions of power.

The ABC’s Media Watch takes up all these themes in its observations of journalists’ behaviour. It’s worth watching because its video clips of media events convey the atmosphere of media confrontations faced by the opposition leader. Paul Barry notes that the ABC itself boosted the importance of the six points incident when it incorporated it into its nightly TV news.

Hardaker ascribes some of the problem to the practice of televising politicians’ press conferences, providing a public stage for ill-mannered narcissists.

In conclusion, reflecting on journalists’ behaviour in the campaign, he asks rhetorically “Is it good journalism?”. “In my view the answer is ‘no’. It is cheap and nasty, and is done with one intent – to catch the leader out. It’s no wonder so many of the public hate the media”.

The debate that didn’t happen

In a country with a well-regarded independent national broadcaster, one would naturally expect that it would be host to at least one debate between contending political leaders.

Even though the ABC has been able to cover National Press Club debates between ministers and their shadows, it has been shunned by the prime minister, who has agreed to debate the opposition leader only on commercial media.

Writing in The Saturday Paper – Why is Scott Morrison dodging the ABC? – Rick Morton describes the way the ABC has done everything it can to provide Morrison with a platform for a national debate in prime time, and how the prime minister’s office has done everything it can, short of a categorical refusal, to decline the invitation.

Morton sees the issue mainly in terms of the Coalition’s ingrained hostility to the national broadcaster, particularly since Tony Abbott became their leader. He also draws attention to the way the tabloid press and some other commercial media have been so fawning towards Coalition politicians, while going out of their way to dig up dirt on Albanese and independents.

Morrison may be disappointed, however, with his choice of media. Even Sky acknowledged that Albanese won the third debate. Morrison may have done a little better had he been on the ABC in a debate moderated by one of its well-regarded and well-qualified economic experts.