Economic basics – productivity and structural change

At last – a media story on the economy

So far in this campaign there has been little media coverage of economic policy. A few economic indicators have come to prominence – the unemployment level for Coalition bragging rights, interest rates and consumer prices for Labor censuring rights – but there is little reporting on the policies that have led to these figures. There is some coverage of fiscal matters – deficits and debt – but fiscal policy is only a minor component of economic policy.

Last Saturday Geraldine Doogue broke that silence in a Saturday Extra interview with Peter Harris, former chair of the Productivity Commission, and Melinda Cilento of the Committee for Economic Development of Australia (CEDA): Desperate need for economic policies with long term benefits.

Their focus was productivity, attributing our declining productivity to a neglect of policies to advance structural change. Governments do not have to direct the economy, but as was the case with the Hawke-Keating government, they can work with business to promote structural reform, can lay out consistent and clear policies (climate change as an example), and can make sure that their policies do not work against structural reform.

They described the simple economic reality, that without productivity there can be no sustained wage growth. (A listener reminded them that while that is true, there can be productivity improvement without wage growth, if all the productivity gain goes to profits. That seems to be what has happened to the small productivity gains Australia has experienced in recent years.)

Much of the discussion was about the political economy of structural reform. It’s difficult for any party aspiring to government to run on a platform of structural reform, because it almost always involves some short to medium-term cost before the gains are realized. Harris, for example, was enthusiastic about policies that make it easier for people to re-visit education in order to re-skill as the economy’s needs change. Cilento mentioned the opportunities involved in de-carbonizing the economy. But such reforms are difficult to promote in a campaign, because the electorate is “fearful and sceptical”.

The interest rate rise: it goes back to the Coalition’s lack of structural reform

In 20 of the last 26 years, the Coalition has held office, but in that period it carried out only two economic reforms – replacing a messy mix of sales taxes with the GST, and making the Reserve Bank independent of executive government.

On Tuesday that latter decision came back to bite the Morrison government.

Morrison might justifiably argue that an interest rate rise on his watch was inevitable: at the time of the Dutton-Morrison putsch in 2018 official rates were already low – 1.50 per cent – on their way down to 0.10 percent. They were bound to rise at some time.

As RBA governor Philip Lowe said after Tuesday’s decision “the Board judged that it was appropriate to start the process of normalising monetary conditions”.

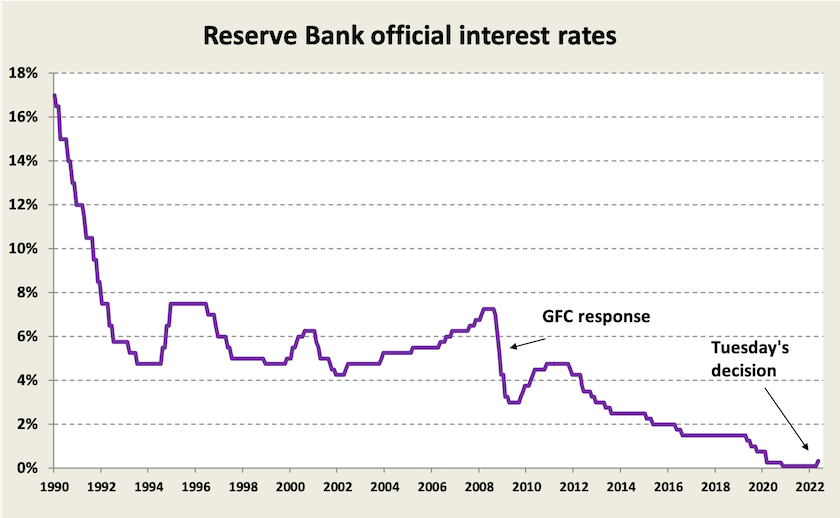

When we look back at official rates over the last 30 years, shown in the graph below, they have generally been well above 4.0 percent. If that’s “normal”, on Tuesday the RBA did no more than to take a few baby steps.[1] As Lowe said, he expects further increases in interest rates will be necessary over the months ahead. In support of the decision the bank expects inflation to be around 6 percent this year. That’s much higher than the 3.00 to 4.25 percent presented just last month in the government’s Pre-election Economic and Fiscal Outlook.

While it would be unfair to blame this week’s and future rises entirely on Morrison, his election handouts have contributed to the problem.

For the most part the Morrison government has inherited the problem from its Coalition predecessors. They have left the Morrison government with a low-growth economy unable to recover fully from the shock of the GFC. Our economy was being kept on life support with low interest rates well before a cruise ship brought Covid-19 to our shores: in January 2020 the official rate was already down to 0.75 percent.

The basic problem comes back to economic reform, or the lack of it. Had successive Coalition governments attended to structural reform as the Hawke-Keating government had done, directing reforms to raising productivity, there would have been no need to have bring interest rates down to such low levels in the first place. There would not be a housing bubble about to deflate, there would be lower levels of household debt, and there would not have been a nasty pre-election shock. Had real wages been rising as a result of economic reform we would now be able to absorb foreign-induced inflationary shocks with far less pain.

But Coalition governments, apart from the two reforms mentioned, generally worked to thwart structural reform. Howard introduced changes to capital gains tax that discouraged long-term investment while encouraging asset speculation, including housing speculation. From opposition Abbott allied with mining companies to run a massive scare campaign against the Rudd government’s resource rent tax before the 2010 election. When he won government in 2013 his first job was to repeal the Gillard government’s market-based policies on climate change. Successive Coalition governments have deliberately weakened trade unions and undermined principles of central wage fixing, thus keeping wages low and discouraging companies from investing in productivity-improving technology.

As ken Henry pointed out in an article in the Financial Review – Budget $80b worse due to weak productivity (probably paywalled) – had governments over the last 26 years attended to structural reform, particularly to tax reform, the government to take office in two weeks’ time would have a great deal more policy options than are now being offered by the main parties.

Morrison’s part in this neglect and incompetence has been collegiate rather than personal – collegiate because he has gone along with the Liberal Party’s economic philosophy of “small government”, taking policy advice from rent-seekers, and congratulating himself when the economic tide has turned his way. When it comes to his so-called “plan” for re-election, there is not even a hint that a re-elected Morrison government would address structural reform.

That is not to suggest that with more responsible economic policy over the last 26 years the pandemic and other global economic events would have left us unscathed. But had Coalition governments been more honest with the electorate, had they supported the best of the Rudd-Gillard government’s reforms (while still putting forward alternative policies), and had they not made patronisingly silly propaganda about their own economic abilities, Morrison would be enjoying an easier run now.

1. In fact if “normal” means holding rates a little above inflation – that is, maintaining a positive real interest rate – interest rates have quite a way to go. If inflation can be brought down to 2 to 3 percent as the RBA seeks, then to achieve a positive real interest rate the nominal rate would have to be higher than inflation, perhaps in the order of 4 percent. Tuesday’s decision still leaves real official interest rates in negative territory, probably around minus 3 percent. (The RBA rate is 0.35 percent, and the trimmed mean inflation is 3.7 percent, meaning the real rate is around minus 3.2 percent ((1.0035)/(1.037) – 1).) For most of the time between the GFC and the start of the pandemic the real rate was no lower than minus 1.0 percent. Rates have been negative since the GFC, but not as negative as they are now . ↩

Phasing out coal – a case study in structural change

Historically the Ruhr Valley (the Ruhrgebiet) was the place of coal mines, steel mills and heavy manufacturing, peopled by a proud and male blue-collar workforce.

The Ruhr Valley today – Duisburg, Oberhausen, Essen Bochum, a host of smaller cities, and the surrounding countryside – is something entirely different. The air is clean, the buildings are free of grime, services and high tech dominate its industrial landscape, and the region hosts five major universities. It was even designated as one of Europe’s cultural capitals in 2010.

The ABC’s Rear Vision has a program – Germany’s Ruhr – from coal mines to culture – explaining how this transformation took place. It didn’t just happen. Rather it was guided by cooperation between governments (federal, state and city), unions and companies. It’s a story of structural change on a grand scale, in a region with a population around the same size as New South Wales.

In many ways that transformation was similar to the structural adjustment programs of the Hawke-Keating government, scaled up, but it was also more comprehensive, particularly in terms of the new activities that were encouraged to be brought into the region.

The Ruhr transformation wasn’t perfect: the Ruhr still suffers some of the problems of the world’s former heavy industry regions, but on a much lesser scale. As is so often the case, local and business interests held off for a long time, resisting and denying the inevitable. As a result the process started later than it ideally should have, and was more expensive and drawn-out than it need have been.

Towards the end of the program there is a short discussion of the relevance of the Ruhr model for Australia, particularly for our coal-fired power station regions. Our export coal industry, however, presents more difficult problems that are not entirely suited to the Ruhr approach.

While Germany has made good progress on phasing out coal mining (there are still large coal mines in eastern states), it is heading in the right direction. The same cannot be said of China, however, where coal-fired power stations are still under construction. (It’s strange that western governments understand and often overstate China’s military threat to the world’s safety and security, but they tend to neglect its voracious demand for coal, which also threatens global safety and security.)