The Coalition’s dwindling claim to economic competence

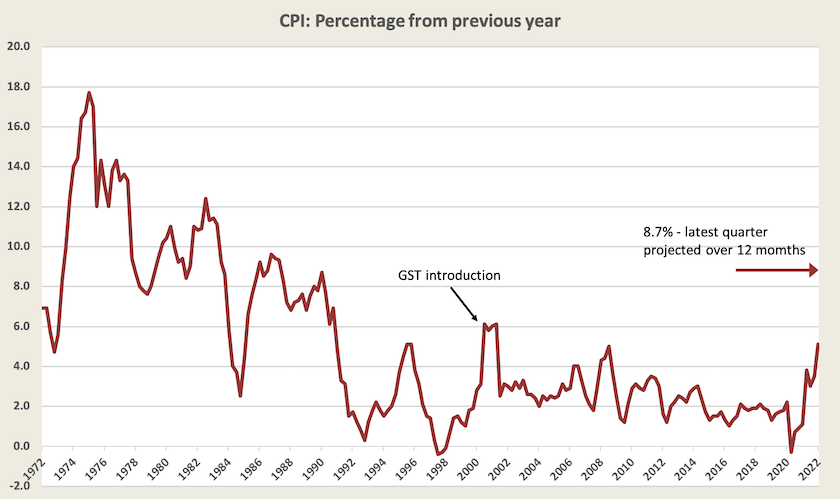

Inflation now at 8.7 percent: interest rate rises to follow

As widely reported inflation as measured by the CPI was 5.1 percent for the year to March.

That’s really a conservative reading of ABS data. Over the March quarter the CPI rose by 2.1 percent, a rate which if sustained, would result in annual inflation of 8.7 percent over 2022. Because there is no evidence that prices have stopped rising in the current (June) quarter that 5.1 percent figure is almost certainly an understatement of inflation going forward.

The graph below shows inflation, as measured by the CPI, over the last 50 years – ever since the turmoil of the collapse of the Bretton Woods agreement in 1972. Leaving aside the GST rise in CPI, which should not be classified as inflation, the last time the CPI hit 5.1 percent was in 1995.[1]

The ABS has other measures of inflation, most notably the “trimmed mean”, which excludes large prices and falls (such as once-off movements in fuel prices), but even that was 3.7 percent over the year to March, the highest since 2009. Over the March quarter it was 1.4 percent, which if sustained, would see annual inflation of 5.7 percent, still well outside the Reserve Bank’s 2 to 3 percent comfort zone, and higher than the 4.25 percent predicted earlier this month in the Pre-Election Economic and Fiscal Outlook.

The measure most relevant to people struggling to make ends meet is what the ABS calls “non-discretionary inflation”, which rose by 3.0 percent in the March quarter (equating to 12.5 percent annual). The price of “grocery food products” rose by a whopping 4.0 percent over the quarter: anyone who has been into a supermarket doesn’t need the ABS to tell them that.

Politically this has further undermined Coalition claims about its superior economic management, particularly as it raises the probability of a rise in official interest rates on Tuesday.

In a less-polarized political environment people would be cutting the government some slack, because the task of managing fiscal and monetary policy during unpredictable waves of a pandemic has been much more difficult than in a normal business-cycle recession. But over many years Coalition prime ministers and treasurers have misled and lied to the public about economic indicators, particularly when the Rudd-Gillard government successfully navigated our economy through the global financial crisis. Having blown its credibility, the Coalition should not be surprised if those who once believed their spin about their economic competence now turn on them.

If we take a longer view, the main reason why wages are now falling behind the cost of living is to do with our economy’s faltering productivity performance, and that is something for which Coalition is responsible. Successive Coalition administrations – Howard, Abbott, Turnbull, and now Morrison – have largely ignored the task of economic reform, restricting their economic policy to the bookkeeping task of fiscal management.

1. Although the CPI is generally used as a measure of inflation, it’s really only a measure of household prices, whereas to economists “inflation” refers to price rises throughout the economy. The GST price rises were only at a household level, and were compensated with other tax cuts and transfers. ↩

The Coalition fails on its own fiscal criteria

In last week’s roundup we provided a link to the Pre-Election Economic and Fiscal Outlook – the “PEFO” – pointing out that it was essentially a cut-and-paste from the budget papers, incorporating the government’s dismal outlook for wages.

Alan Austin has gone through the PEFO, comparing the Coalition’s fiscal claims with the actual record of fiscal outcomes under Coalition governments. He tests, for example the Coalition’s claim that “Under the Coalition, spending will always be less and tax will always be lower than under Labor.” It’s just not so: in fact the diametric opposite has been the case. So too with government debt. Almost every country has had a big increase in government debt over the last two years, but Australia’s increase in debt has been almost the highest in the OECD, even though we have been comparatively lightly affected by the pandemic.

Of course there is more to economic management than balancing the fiscal books – much more – and there is no intrinsic virtue in keeping taxes low if that is at the expense of providing necessary public goods and investments. But the point of Austin’s article – Department heads give worst ever economic report after eight Coalition years – is that even by the narrow fiscal criteria the Coalition has set as metrics of economic management, their claims don’t add up.

Confirming Austin’s analysis the RMIT-ABC Fact Check has examined Jim Chalmer’s claim that the current government has borrowed and spent more than Labor did, and has found his claim to be correct.

Commenting on that finding, Saul Eslake and Chris Richardson warn that in themselves raw numbers on fiscal measures tell us little about the values or capabilities of governments. That’s a valid point, stressed by many economists over many years, but the Liberal Party, supported by journalists who have been too biased or inadequately educated in economics, has made fiscal outcomes the be-all and end-all of economic management.

If the Coalition were to be assessed on economic policy generally, and not just on fiscal indicators, its report card would be even worse than the one Austin has provided. Because successive Coalition governments have failed to attend to fundamental economic problems we have a structurally weak low productivity economy. Structural repair will be a much more difficult task for our next government than the comparatively simple task of “budget repair”.

How the Liberal Party has failed on its conservative credentials: home ownership

It would be hard to think of a more bourgeois political aspiration than home ownership. Home ownership ticks all the conservative boxes, as young people take roots in local communities and establish families.

Morrison makes much of the Commonwealth’s relaxation of criteria for first home owners’ grants (which in themselves only add to demand-pull house price inflation), but the reality is that on the Coalition’s watch home ownership, particularly among younger people, has been falling.

Ross Gittins draws our attention to the way declining home ownership has been a failure by so-called “conservative” politicians to live up to their own ideals: If you care about our future, care about declining home ownership. In fact through their tax policies thay have done much to privilege speculators over those who seek to establish families.

Income and wealth distribution: we’re becoming more unequal

The day after the ABS released the CPI, it also released its survey of household income and wealth for 2019-20, with comparative data going back to 2009-10.

To pick out a few points:

There has been very little growth in real household disposable income since 2008 – around 7 percent.

Any ideas that we live in an egalitarian society is dispelled by their figure (Graph 3) on the distribution of household net worth (assets minus liabilities). The mean household net worth is $1.04 million, but the median is only $0.58 million. Most households are clustered around a net worth of about $0.10 million.

There have been significant movements in wealth distribution. Our distribution of wealth is far more unequal than our distribution of income. For example, in 2009-10 there were 140 000 households with more than $5 million in net wealth (in constant 2019-20 prices); by 2019-20 that number had risen to 230 000. Other households have had a rise in wealth, but by a far lesser extent.

Over the same period the proportion of households with debt of 3 or more times income has risen from 24 percent to 30 percent.

Much of the increase in reported wealth is in owner-occupied real estate. In simple terms the poor generally don’t own houses; the rich own houses but they have plenty of financial assets as well; those between own houses and not much in other assets. When house prices fall, the main wealth effect will be felt by middle-wealth households.

These statistics relate only to wealth that can be quantified in dollar terms. They cannot pick up other wealth disparities, such as access to good schooling and safe neighbourhoods. Nor can they pick up the disparities in early life, such as the home environment in which children grow up. That’s why early childhood development is, or should be, such an important policy issue: it’s not only about freeing up parents so they can do paid work.

Universities: how to re-build after four difficult years

Universities have suffered four years of hostility from the Morrison government, and two years of coping with Covid-19. The Morrison government has found that hostility to universities (and to any institutions of academic or intellectual rigour) has played well with parts of its electoral base. In addition, the pandemic has virtually halted the flow of international students, and has required universities to adopt remote learning practices, denying students the collegiate support normally found on campus. On top of these stresses was the Morrison government’s decision to exclude public universities from “Jobkeeper”.

These are some of the problems Geraldine Doogue discussed with ANU’s Ian Anderson, deputy vice-chancellor of student and university experience, on last week’s Saturday Extra: A path forward for Australian universities. Anderson, in an exercise with colleagues in other universities, has been working on ways universities can re-build themselves to become more resilient. The results of that work are in his paper, co-authored with Robert Griew, The future of the university sector post Covid-19.

Anderson sees a need for universities to connect better with their communities, including with their students. Perhaps because universities have been too concerned with serving international students, and perhaps because of traditional problems of universities becoming too detached from their surroundings, neither the communities nor the students were there to defend them when they came under attack from the Morrison government.