The campaign: will someone please start talking about public policy

What’s really at stake: integrity, climate change, other aspects of economic management

While Morrison travels the country looking for photo opportunities involving fluoro jackets, hard hats and big machines, and Albanese tries to explain Labor’s policies to journalists who have little understanding of economics, there are voters out there with concerns about things that will affect their lives.

A strong anti-corruption commission

Although Barnaby Joyce believes Australians couldn’t care less about whether or not we have an anti-corruption commission, a poll by the Australia Institute finds that 75 percent of Australians want a Commonwealth Integrity Commission or a National Anti-Corruption Commission, with strong powers, and that 43 percent of respondents consider it to be a major election issue.

Climate change

The Conversation is trying to fill the gap between political posturing and policy choices with a survey of its readers #SetTheAgenda: What The Conversation’s readers want politicians to address this federal election. So far climate change tops the list, followed by “the environment” more generally, cost of living, misinformation and housing. A broadly similar ranking is revealed in the ABC’s Vote Compass. Preferences of ABC patrons and The Conversation’s readers may not be very representative of the electorate as a whole but they probably reflect views that could be influential in Liberal-held urban electorates.[1]

Peter Christoff of the University of Melbourne, also writing in The Conversation, goes into detail about the electoral politics of climate change: Climate policy in 2022 is no longer a political bin-fire – but it remains a smouldering issue for voters. Because public anxiety about climate change is growing it should be a more prominent issue in this election than it was in 2019, but it is unlikely to change representations in seats that are most affected by fires and floods because most of these are already safe Labor seats.

He also presents a table outlining differences between Labor and Coalition policies on climate change. Labor policies fall short of what is required but they are much more responsible than the Coalition’s – a point that seems to be missed by those who, in fear of being seen as “partisan”, falsely complain that both parties have the same weak policies.

Economic management – why do people believe the Coalition?

The most recent Resolve Strategic poll asks respondents which party would be more competent in handling major issues – “economic management”, “national security and defence”, “healthcare and aged care”, and “education”. The Coalition comes out way ahead (43:23) on “economic management” and on “national security and defence” (43:21). There is little difference on other issues.

In view of the collapse in productivity, stagnant wages, the growth in precarious work, unaffordable housing, general inflation, incipient steep rises in interest rates, high household debt, a resource-extraction economic structure exposed to commodity cycles, struggling public services, declining school education standards, corruption in public expenditure, stressed infrastructure, and widening wealth inequality, any economist unfamiliar with Australia’s political situation would be flabbergasted to believe that the party that’s been in office for eight years would have the gall to campaign on its economic record. (On the Coalition’s other leading issue, its security record has been rather tarnished by its “worst foreign policy blunder” since the end of the Pacific War.)

Similarly the most recent Essential poll finds that most people believe unemployment and interest rates would be higher under a Labor government than under a Coalition government.

Why is there such a divide between perception and reality? A partisan press? Economically illiterate journalists? The accumulated impact of decades of the Coalition lying about the economy? – “If you tell a lie big enough and keep repeating it, people will eventually come to believe it”.

The Labor Party, in spite of its sound economic record as having steered the nation through difficult structural change, and in spite of having economically responsible policies on climate change, health care and education, seems to have difficulty in expressing its policies and principles in an economic framework.

1. The ABC claims, however, that its Vote Compass results have been weighted to be representative of the whole population. ↩

That debate: some detached comments

Australia still has a well-respected and trusted national broadcaster. That is where we would expect to find a debate between contenders for public office, but presumably because Morrison did not want to argue on such a forum, the debate was on an obscure commercial cable outlet.

That leaves us reliant on others’ selective observations, and there is no shortage of these, mostly with a partisan perspective.

The Conversation has brought together three political experts to provide their views on the debate: No magic moments: 3 Australian politics experts on Morrison and Albanese’s first election debate.

They all note that there were no knockout blows. At times, in fact, because the audience was asking questions, the debate got on to public policy, which must have left journalists feeing confused and disappointed.

Andrea Carson of La Trobe University notes the civilized tenor of the debate, and the conspicuous absence of climate change from the agenda.

Paul Williams of Griffith University provides a formal rhetorical analysis of the way each handled questions. On that basis he considered Morrison to be the better performer. (But does Morrison’s “machine-like recitation of statistics” indicate that he has any deep understanding of the meaning of those figures?)

Rob Manwaring of Flinders University tried to find policy differences between Morrison and Albanese. He suggested that there were differences on refugees and on China’s military expansionism, but does anyone really think that Labor would not be tough on people smugglers and on foreign influences in our region?

One real difference he did identify, however, was on funding for NDIS. Although neither Albanese nor Morrison elaborated on the issue, policies towards NDIS, and by extension towards education, health care, child care and other human services, are at the core of Labor-Coalition differences. These services are bearing the consequences of the Coalition’s “small government” political obsession. They would receive greater attention and funding under a Labor government.

Another difference is on economic reform. Albanese, in responding to Morrison’s claims about the Coalition’s capacity for economic management (a belief based on faith rather than on reason or evidence), pointed out that Labor governments, in contrast to the Coalition, have a solid track record on economic reform.

Those are the views of political scientists – learned people whose concerns are often more about tactics and processes rather than any normative view on consequences. Of the 100 undecided voters who constituted the audience, 40 gave the debate to Albanese, 35 gave it to Morrison, and 25 were undecided.

What a civilized political contest would look like

“The federal election campaign descended quickly into a game of political gotcha. The two major parties are focussing on leadership stumbles and scandal. So is it possible to create a politics where there are clear distinctions and where there is also a commitment to the common good?”

That’s the rhetorical question with which Andrew West introduces the segment Can we reinvent a politics of virtue and the common good? on the ABC’s Religion and Ethics program. Two guests, Kate Harrison Brennan and Gray Connolly, answer his question in the affirmative by showing the convergence of “left” and “right”, or “progressive” and “conservative” perspectives around a shared notion of the common good.

Connolly describes the essence of conservatism in a way that clearly differentiates it from other movements of the right – libertarianism, crony capitalism, and “small government”. Rather it’s about holding on to what we value and protecting society from the ravaging force of an uncontrolled market. He has strong observations on housing: a set of policies that has made housing unaffordable is quite out of line with the conservative value of encouraging family formation.

Both agree that the political debate should be about policies. Harrison Brennan notes with regret that the election campaign has degenerated into micro-politics and attacks on character. But as Connolly stresses, character counts: no one has the right to hold high office unless they demonstrate, through their behaviour, that they can be trusted.

The session is 20 minutes long, and is followed by West’s introduction of Stan Grant as the host of the program for the next few weeks. It’s worthwhile spending that last 5 minutes to hear Grant describe why he is interested in religion as a shaper of public ideas, and to get an idea of the themes he might bring to this year’s Brian Johns Lecture on May 31.

Election strategies and advertising – a licence to lie

Writing in The Conversation – How each political party’s election ads reveal their key messages – Tom van Laer of the University of Sydney outlines the main parties’ election strategies. The Liberal Party’s strategy is simple – convince people to hold Albanese in contempt so that people want nothing to do with him. “Such a response is seldom reasoned, which can make it difficult to counter” he writes. The National Party’s approach is transactional (as it always has been). Labor is following a political line of campaigning on traditional strong Labor issues – Medicare, child care, power bills and so on.

Since van Laer wrote his article Morrison has ramped up his scare campaigns about Labor policies, including Morrison outrageously accusing Albanese of treason. Labor has reciprocated in a tit-for-tat about welfare cards.

Morrison has also gone strongly against his own party colleagues in New South Wales in defending Katherine Deves, his hand-picked Warringah candidate, who has made gauche and offensive remarks about transgender children. Deves has little chance of winning against incumbent Zali Steggal, and her campaign could even hurt Liberal’s chances in other Sydney electorates it is defending. But this isn’t about contesting a seat. Rather it’s about publicising Deves’ views which many reasonable people would see as bigotry, but which would resonate with the views of those on the far right, particularly the so-called “religious right”. Remembering how they got him over the line in 2019, Morrison is once again seeking preferences from One Nation and UAP voters.

Anika Stobart of the Grattan Institute, writing in Open Forum – No holds barred in Australian political advertising – points out that, unlike advertising for most consumer goods and services, there are few restrictions on political advertising. Only in South Australia and the ACT are there laws regarding truth in political advertising, but at the federal level anything goes, just so long as the parties sponsoring advertisements are identified and there are no misleading statements about voting rules.

She writes that “deliberately false and misleading advertising hurts the democratic process. It can divert voter attention from the real issues and potentially distort election outcomes”.

Re-writing history

Remember Winston Smith’s job in the Ministry of Truth, in Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-four? His task was to “correct” records to ensure that they aligned with the current political narrative – a reference to the practices in Stalin’s Russia.

Such revision is also occurring in Morrison’s Australia. A reader has brought to our attention significant amendments to the parliamentary Hansard, reported by Dana Daniel in The Sydney Morning Herald: Mystery solved over Hansard change to hide budget’s missing $10 drug price cut.

As part of the Commonwealth’s budget, presented last month, there had been a plan to reduce by $10 the price of medicines dispensed under the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. That proposal was dropped, and not included in the budget.

In speeches after the budget Senator Jane Hume and Assistant Treasurer Michael Sukkar both referred to the $10 cut as a government achievement. When Hansard appeared a few days later these mistaken references had been edited out, following a request from Senator Hume to the Department of Parliamentary Services. That department is supposed to be an apolitical agency, but in this instance it has yielded to pressure to protect two Coalition members of parliament from embarrassment.

Anyone who has appeared before a parliamentary committee would be aware of the strict rules around editing Hansard records. Punctuation can be changed to improve grammar, spelling can be corrected, minor grammatical issues can be attended to, but meaning cannot be changed.

Hume and Sukkar weren’t lying, but they made mistakes – mistakes with possible consequences, because people who heard their statements may believe prescriptions will be $10 cheaper and become more favourably disposed to the Coalition. Yet they have been able to change the record, as if they never made such statements in the first place.

This subsequent “correction” would appear to be far more serious than an opposition politician stumbling over a couple of economic parameters, but apart from Daniel’s article, which correctly focuses on the “correction” rather than the mistake, there has been hardly any media mention of this instance of politicization of democratic institutions.

Opinion polls are telling a story, but not the one the media’s telling

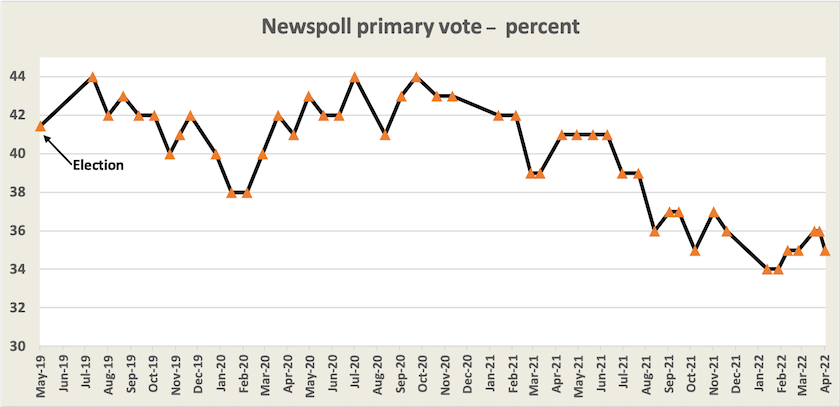

The graph below shows what looks like an irreversible fall in a party’s primary vote since the 2019 election. Perhaps over the last two months the party has come off its low, but that could be no more than a dead cat bounce. While there is noise in month-to-month figures, the trend is clear.

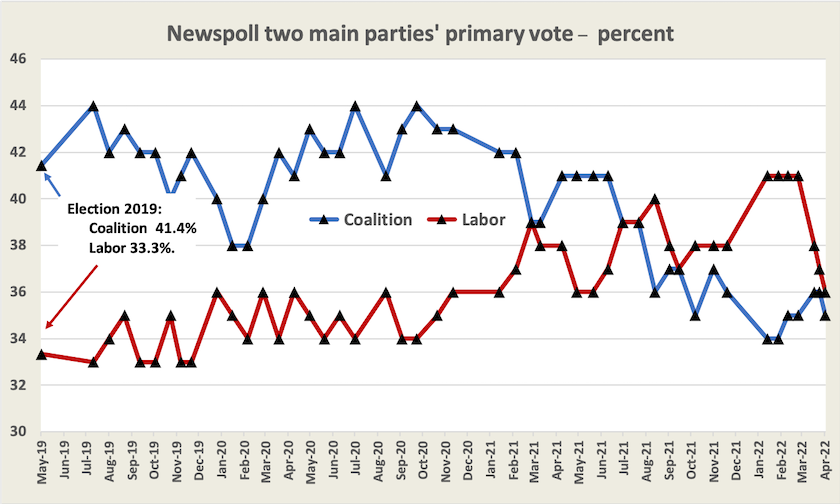

As a reminder, that’s the Coalition primary vote – a five or six point slide since the last election which they won only by the narrowest of margins. The more complete context, showing both main parties’ primary vote on the same scale, is in the graph below.

Most media have focussed on the fall in Labor’s support since the beginning of this year, and in the corresponding tightening of Labor’s two-party-preferred lead, now down to 53:47 in Newspoll. Albanese pays a price for bad week as voters swing back to government is the headline in David Crowe’s report of April 17.

But there is little evidence of a swing “back to government”. A swing away from Labor does not equate to a swing to the Coalition. There are others in the contest.

One journalist who has picked this up is Crispin Hull: Govt’s persistent low primary vote. His summary is:

For the first time we have a three-way race, and the third horse is a dark horse indeed. It is a collection of minor parties and independents who could easily change the face of Australian politics. This is because with the drop in Coalition first preferences, the three horses sit almost equal: 35 Coalition, 34 Labor and 31 the rest.

Hull’s point is that once the Green + right-populist + other vote reaches levels close to the support enjoyed by the established parties, the two-horse assumption that preferences will end up with one of the main parties no longer holds. (In fact the Labor + Coalition primary vote has been falling for 70 years.) Hull is quoting Resolve Strategic figures, but these are very close to Newspoll’s – any difference is within the two polls’ margin of error.

John Hewson, writing in The Saturday Paper – Independents versus a broken system – also draws our attention to what other media is not noticing, or is choosing not to notice. He seems to be throwing his weight behind independents:

If the independents are prepared to make it clear that they will only support initiatives to deliver better government, with a national integrity commission to enforce accountability, it would be a dramatic improvement on what the LNP has delivered, wasting public monies in pursuit of their political ambitions, ducking clearly defined responsibilities, blaming others and obfuscating on the detail of issues just to move on. A hung parliament dependent on independents could trigger an end to this appalling age of entitlement.

Like Hull, Hewson’s main point is that the mainstream media is heavily invested in the two-party system, a system which makes it easy for partisan media to make a simple choice to pick one side over the other.

Other polls

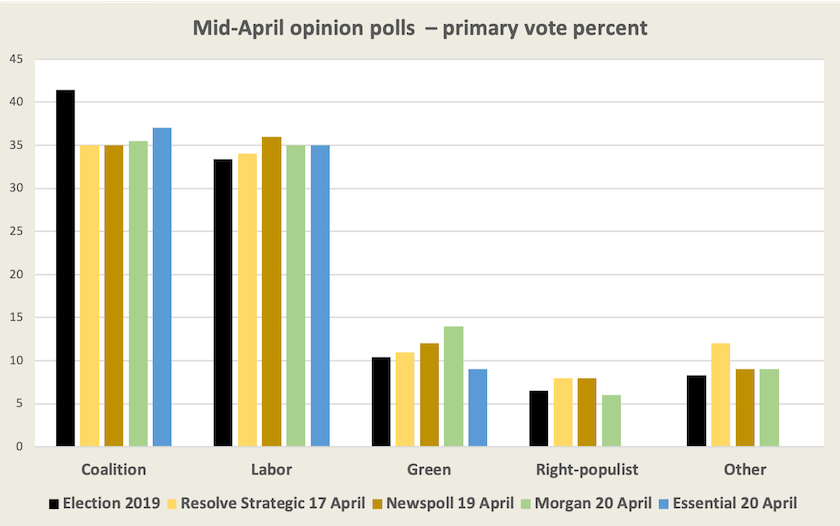

In the last week there have been four polls with very similar figures for parties’ primary support.

A snapshot of these poll results is shown in the graph below, with the 2019 election in black as a reference point.

All but Essential report the One Nation and UAP vote, while Essential simply covers the Coalition, Labor and Greens, lumping the rest into “others” with 11 percent support. In the graph I have combined One Nation plus UAP into a “right-populist” group.

Newspoll shows some strengthening in support for the Greens over the last few weeks, there now being enough data points to be significant. Maybe some Labor support is transferring to the Greens. The right populists may be gaining some ground, possibly one or two percent, but the main gain seems to be going to “other”, probably prominent independents.

Although the polls are reasonably similar on primary voting intention as the graph shows, there is wide divergence on their two-party-preferred calculations: Morgan shows a 55:45 TPP lead for Labor, Newspoll 53:47, and Essential 47:46 (without allocating 7 percent undecided voters). TPP results depend on a wide range of assumptions that are difficult to verify. All we can reasonably say at this point is that while the Coalition vote has fallen significantly since last election, Labor has gained only a little, and Greens, right-populists and independents seem to have picked up support.

Some polls have some disaggregations on a state basis, but these samples are inevitably small. Resolve Strategic has a gender disaggregation, which does have a reasonable sample size. Women don’t like the Coalition, but they haven’t turned to Labor. In primary voting intention men are 38 percent Coalition, 33 percent Labor, while women are 32 percent Coalition, 35 percent Labor.

The Newspoll results are available from William Bowe’s Poll bludger. Resolve Strategic’s poll is in Crowe’s Sydney Morning Herald article. Morgan’s poll is on its own site, as is Essential’s.

Why Morrison will be returned to office: it’s in the figures

Some psephologists say that we don’t need opinion polls or betting markets to predict who will win the election. One of their contributions is a simple and supposedly reliable mathematical model with just two variables – unemployment and inflation – which points to who will win the election. If inflation is low, and if unemployment is falling, the incumbent will be returned to office. Although inflation is emerging as an issue, falling unemployment is the stronger variable. So Morrison will be returned to office.

The model and its past success, is described by Peter Martin in The Conversation: This economic model tipped the last 2 elections – and it’s now pointing to a Coalition win.

Peter Martin isn’t so rash to over-estimate the model’s predictive power, but he does draw our attention to research that confirms or negates our beliefs about variables that might predict voting intention. As a contribution he reproduces a scatter diagram from an article in the Australian Economic Review that shows a strong correlation between people voting “no” in the same-sex marriage poll in 2017 and voting for the Coalition in 2019.

The article has stimulated a rich series of comments.