The pandemic – it’s still raging

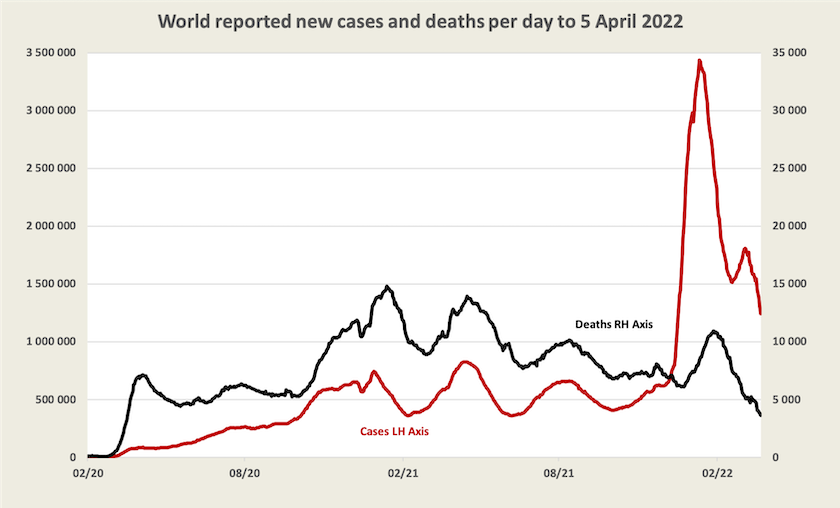

World – cases and deaths falling, but keep an eye on China

For those countries that record cases and deaths, both are continuing to fall. Recorded deaths are now lower than at any point since the pandemic became established two years ago.

If deaths are so low while cases are still high, an incautious conclusion would be that the virus has become less deadly. Perhaps that is the case, but there are many other plausible explanations – more cases are being detected than previously, some deaths of people who die with Covid-19 but not of Covid-19 are now not counted as Covid-19 deaths, cures are improving …

Most “developed” countries record a fall in cases, but deaths are still rising in some countries where cases are falling, presumably reflecting the lag between infection and deaths. Australia is one country where cases and deaths are still rising, probably because the Omicron wave, thanks to remaining state-based isolation measures, has come here later than in other countries.

Another country where cases are rising is China. It’s experiencing about 10 000 new cases a day, about the same number as Victoria but China is a little larger than Victoria. Last week it appeared that strong measures in Shanghai may be succeeding in containing its spread, but cases are now on a strong exponential growth pattern, doubling every 8 days. The virus has spread to other cities, and is starting to exact an economic toll. If it is not contained, and continues to grow at the same rate, everyone in China will have been infected by mid-July. The death toll may not be high, but whatever approach the country takes to manage the virus, the economic consequences for China and therefore the world could be significant.

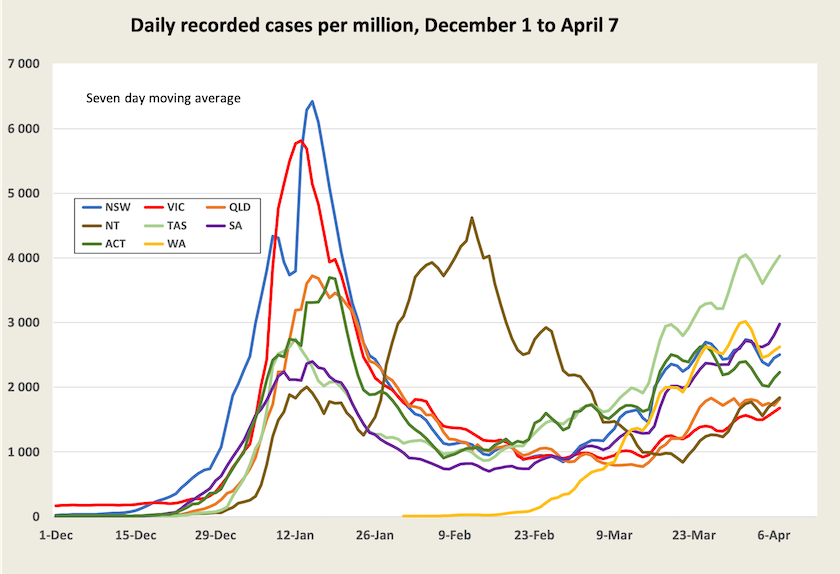

Cases in Australia are rising but so is complacency

As the highly infectious BA.2 variant spreads, cases are once again rising in all states and territories. Note that in Tasmania and South Australia, states that were quite late in lifting travel restrictions, cases are now higher than they were in the Omicron BA.1 wave.

Nationally there are around 60 000 recorded cases a day.

More background to these figures is given by Casey Briggs, on the April 1 ABC The Virus program. (15 minutes) He points out that the virus is spreading most quickly among people under 40.

His segment is followed by comments from Alexi Boyd from the Council of Small Business Organisations and Thomas Costa from Unions New South Wales, on the virus’s effects on people in business. Staff absences are rising once again, either because someone has Covid-19 or is isolated as a close contact of someone else who has Covid-19. Many businesses are struggling to stay open, and many employees are using up their sick leave, while casual workers who have no sick leave, are once again disproportionately bearing the costs of the pandemic.

As a back-of-the-envelope calculation, on any one day perhaps five percent of workers may be absent.[1] Because the virus spreads in workplaces, it is likely to be much higher in some businesses with locationally concentrated workforces.

Based on official records, by now just on a quarter of everyone in New South Wales will have been infected since December in the Omicron wave. (The figure is lower in other states where the variant broke out later, but they are catching up.) New South Wales health practitioners believe the actual number of infections could be at least twice the number recorded, in which case the virus is about halfway through its spread in New South Wales. If that is the case, we may see some levelling off and a slow decline in cases in the next couple of weeks, provided there is not a high rate of re-infection. Other states should follow. In the last segment of the ABC’s The Virus program John Kaldor of the Kirby Institute describes research designed to see how many people, by age group, have been infected by Covid-19 in the Omicron wave. The results won’t be precise, but they will give a truer, and presumably higher, estimate of the extent of the infection’s spread. This is important information for planning in the business sector and in the health and education sectors.

Epidemiologist Tony Blakely, writing in The Conversation, suggests that case numbers in New South Wales are already plateauing.[2] He also notes that many people are strengthening their immunity through having had Covid-19 in this latest wave. That is not to suggest the virus is in its final stages: it is still a dangerous illness for the old, the ill and the unvaccinated, and there remains the possibility of more virulent variants. But provided the hospitalization rates do not rise to a level that will overburden the health system, it shouldn’t be necessary for governments to re-impose restrictions: Covid cases are rising but we probably won’t need more restrictions unless a worse variant hits. (Tony Blakely’s analysis of the situation contrasts somewhat with that provided by Raina MacIntyre, below.)

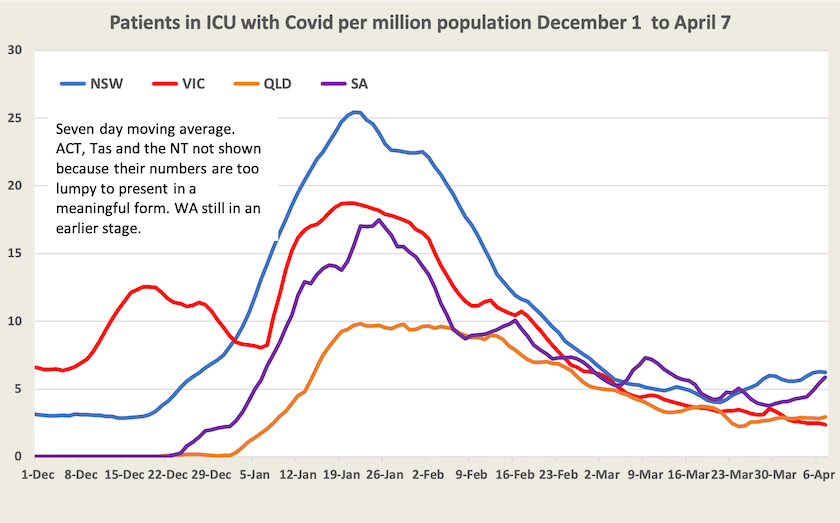

While the impact on business of rising case numbers is immediate, the impact on the health system is delayed. Hospitalization and ICU rates are now rising in New South Wales and South Australia, but are still well below their January levels.[3]

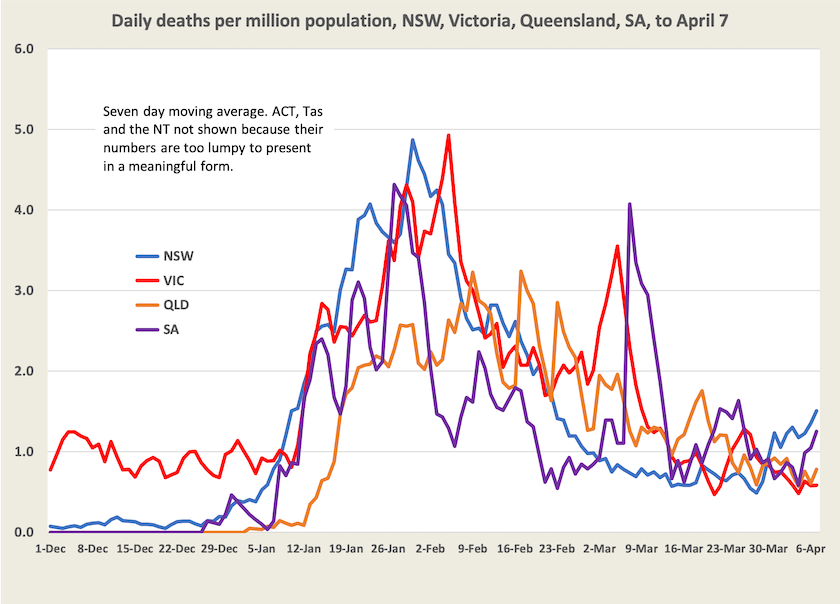

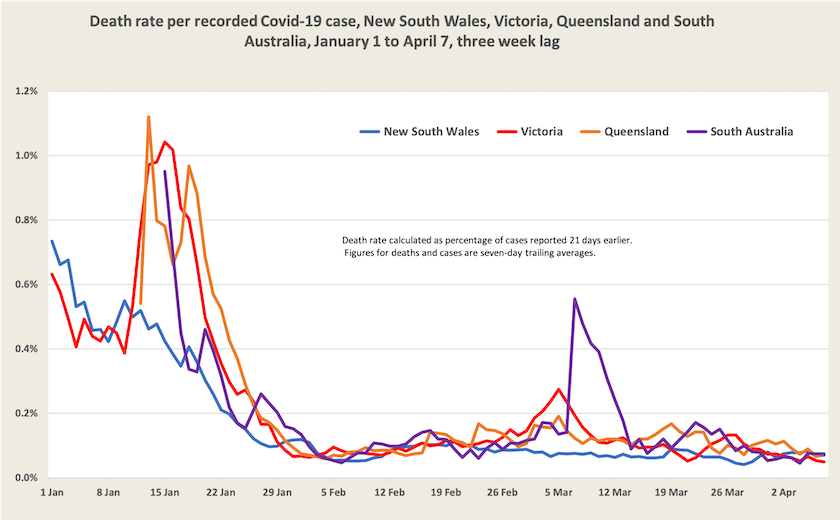

Higher numbers of deaths are starting to show up in New South Wales and South Australia.

But the death rate per case remains low in all four states monitored, and if anything is falling a little – to around 0.06 percent, or around 1 in 1500.

Even though deaths are rising, and will probably continue to rise for a while, the Commonwealth Chief Medical Officcer, Paul Kelly, has announced that the government will stop reporting daily deaths. Rather, the Commonwealth will calculate what is known as “excess deaths”. “Excess deaths” is a useful metric, because it helps put Covid-19 deaths into perspective, and it may reveal that a rise in Covid-19 deaths has been at least partially offset by a reduction in influenza deaths. But it takes a long time to calculate, and it does not serve the same purpose as recording daily deaths, which is a means of real-time monitoring of a disease we still don't know a great deal about.

Could it be that the timing of this announcement has something to do with the coming election? It would be convenient for Morrison if we aren’t given daily death numbers – numbers that remind us that Covid-19 is still around. That would help us forget the Morrison government’s deadly incompetence in handling the epidemic – deaths in aged-care homes, the delay in ordering mRNA vaccines, and the pressure he put on state governments to abandon public health measures.

1. Based on 60 000 infections a day, if each infected person isolates for 5 working days, and infects 4 others, 2 of whom are in the workforce, on any day there will be 600 000 (60 000 x 5 x 2) people away from work, or about 5 percent of our 13 million employed workforce. ↩

2. The graph in Blakely’s article shows a definite plateauing. He and I would be drawing on the same data, but using different methods of smoothing. I am using a seven-day trailing weighted average. A de-seasonalized average, removing the effect of lower case numbers on weekends, would probably show a flatter curve than the blue NSW line in my graph. ↩

3. That is the number of people in hospital or ICU, not the number of people being admitted to hospital or ICUs.. ↩

Vaccination and awareness

While Australia has a reasonably high level of two-dose vaccination (83 percent) , our three-dose level of vaccination is tapering off at 51 percent. Among eligible adults (16+) it ranges from 55 percent in Queensland, up to 76 percent in the ACT. Vaccination levels among indigenous Australians are still lower than for other Australians, but the gap is closing. We are still a long way behind in vaccination for children aged 5 to 11 (30 percent one dose, 53 percent two dose).

On Thursday morning’s ABC Breakfast program Julie Leask of the University of Sydney noted that while we did well with immunization last year, we are now slipping both in vaccinating children and in third and fourth doses for adults: Sluggish rates for booster shots. (8 minutes)

While gross indicators give the impression that we are coming to live with the virus in the same way as we live with other infectious diseases, public health experts are warning that we have become dangerously complacent.

Raina MacIntyre has an article in The Saturday Paper with the headline Why Australia’s daily Covid cases are on the rise again, but it’s more an expression of frustration about our complacency. We have been too quick to stop wearing masks and to give up on simple public health practices. We are not adequately attending to ventilation as winter approaches and as people are more likely to gather inside, and our low death rates are distracting us from considering the long-term effects of Covid-19. She points out, for example, that Covid-19 increases the risk of diabetes in children, and she reminds us of the health effects of “long-covid”, drawing on Britain as an example, where 2.4 percent of the population are living with chronic Covid-related illnesses.

Norman Swan has a 7-minute segment on ABC Breakfast which starts with a discussion of the recombinant BA.1 – BA.2 virus (we don’t know much yet but it is probably not more contagious than BA.2). His greater concerns are about surveillance, a global public health issue. In some regions, particularly in Africa, there is no public health surveillance, and other countries, such as the UK and Denmark which have been informing the world, are scaling back their surveillance efforts. We haven’t learned the lessons of this pandemic – that we have to be on the lookout for new variants before we find out the hard way, and for the emergence of new viruses. He also echoes Raina MacIntyre’s concerns about ventilation.