Elections and opinion polls

Elections in Eastern Europe: populism and admiration of Putin are still strong

Last weekend Serbia and Hungary held elections. Both turned out well for pro-Putin candidates.

In Serbia populist Aleksandar Vučič, the former minister for information in Slobodan Milošević’s government, won 59 percent of the vote in the presidential election. This is up from his 55 percent vote in 2017. His Serbian Progressive Party won 43 percent of the vote in the parliamentary election. That’s a reversal from the 2020 election, but it is still the dominant party in the parliament.

Although it is a member of the EU, Serbia has always had a close relationship with Russia. Russia has used its UN veto, for example, to block independence for Kosovo, and Serbia has refused to join in sanctions against Russia. But it is questionable whether this refusal to cooperate in sanctions is based on historical affections and relationships, or on the fact that Serbia is highly dependent on Russian gas, as suggested by Aleks Eror writing in Politico: For Serbia’s Vučić, the big challenge comes after election day, that challenge being the need to come off the fence and make a stance.

In Hungary Viktor Orbán’s far-right pro-Putin Fidesz Party has won decisively in parliamentary elections, with 54 percent of the popular vote, a swing of 5 percent, while the opposition, a temporarily united front of left and centrist parties, suffered a negative swing of 12 percent. The relatively new nationalist party “Our Homeland”, running on a platform of opposition to LGBT rights and contesting parliamentary elections for the first time, gained 6 percent of the vote.

As in other countries, there was a sharp urban-rural divide. Only in Budapest and Szeged did the opposition gain a majority of votes.

Dora Diseri of Deutsche Welle describes the policies and tactics that Orbán used to retain power, including temporary economic stimuli to help households deal with inflation and cost-of-living pressures. (Familiar!). But its enduring platform has been nationalism and opposition to liberalism, particularly around women’s rights and the rights of LGBT people, as if the only behaviour that should be of moral concern is sexual behaviour. Hungary is three-quarters Roman Catholic, but it’s not the more tolerant form of Christianity, with a concern for social morality, found in western Europe and espoused by Pope Francis.

Diseri reports that The Orbán government has refused to join with other European countries in imposing sanctions against Russia, has not provided arms for Ukraine, has not allowed arms destined for Ukraine to transit through Hungary, and officially considers Vlodymyr Zelenskyy “as an enemy that has allied itself with the Hungarian opposition”.

Although Hungary is a member of the EU, it would be hard to classify it as a democracy. Human Rights Watchdescribes how most media are directly or indirectly controlled by the government, how academic freedom has been curtailed, how women’s rights have been suppressed, and how Orbán’s government has used the coronavirus as a means to rule by decree over matters that have nothing to do with public health.

Putin was quick to send telegrams to Vučič and Orbán congratulating them on their victories.

Lowy Institute polls – Chinese-Australians and Indonesians

The Lowy Institute has published the results of two attitudinal surveys of Chinese -Australians and of Indonesians.

Their survey Being Chinese in Australia by Jennifer Hsu and Natasha Kassam looks at the views of Chinese-Australians on a range of social issues. The surveys were in 2021, using the same questions as a similar exercise in 2020.

It’s a report on immigrants that “express warmth about Australia as a place to live, and pride in the Australian way of life and culture”, although there has been some small fall in these positive sentiments between the two polls. There are still reports of racism from other Australians: a quarter of respondents report having “been called offensive names because you are of Chinese heritage”, but this is lower than in 2020.

A small majority – 57 percent – believe Australian media reporting about China is too negative, up from 50 percent in 2020.

A set of questions about which nations they trust shows them to be more trusting of China than of the United States, and even less trusting of Russia than of the United States. They show less confidence in Anthony Albanese (minus 12 percent net) than in Scott Morrison (minus 3 percent net).

The strongest attitudinal difference between Chinese-Australians and other Australians relates to the stance Australia should take in the event of a conflict between China and the United States: Chinese-Australians are much more in favour of neutrality than other Australians are.

The survey Charting their own course: how Indonesians see the world by Ben Bland, Evan Laksmana and Natasha Kassam finds that Indonesians “are optimistic about the future but wary of the great powers that are seeking to court them”. This being Lowy’s third survey of Indonesia they can identify some trends: for example Indonesians feel much safer in the world than they did on 2016. Since 2011 their trust in Japan, the United States, China and Australia to “act responsibly in the world” has fallen, but perception of a threat from Malaysia has almost disappeared.

They are unenthusiastic about Australia’s decision to buy nuclear-powered submarines, many believing the deal will make Indonesia less safe. They are less inclined to see The Quad as a threat, however.

Australian voter intention polls

Four polls published over the week have a range of estimates of voting intention, ranging from 57:43 to 53:47 two-party preferred lead for Labor.

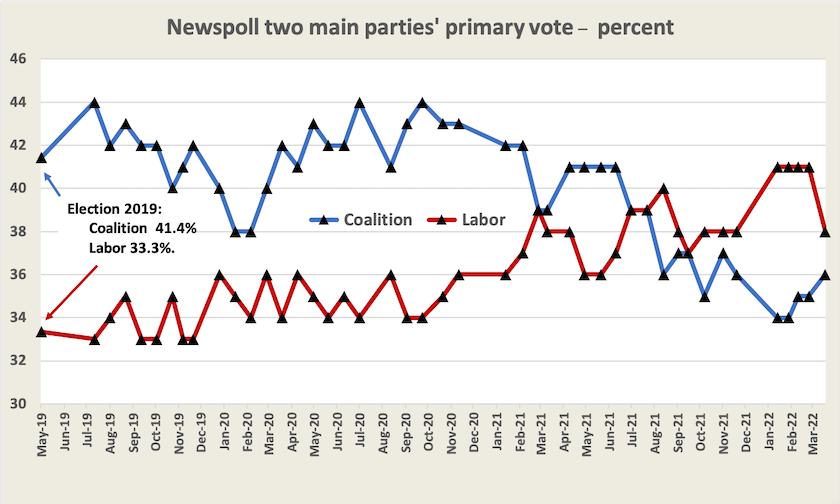

The latest Newspoll, completed last weekend, suggests that there has been some fall in Labor’s primary vote and some strengthening in the Coalition’s primary vote. In round numbers, Labor is up five percentage points from the 2019 election, and the Coalition is down a similar five percentage points. More detail is on William Bowe’s Poll Bludger, where he also reports that the Newspoll shows two-party-preferred support for Labor at 54:46.

In the same post Bowe also reports on an Ipsos Poll, which shows a slightly higher (55:45) two-party-preferred support for Labor. When he assumes the 7 percent “undecided” voters will vote the same way as those who report a preference, he calculates Labor’s primary support at 38.9 percent and the Coalition’s at 34.4 percent. Compared with Newspoll that’s a little higher for Labor and a little lower for the Coalition but well within margins of error for both polls.

The Resolve Political Monitor poll of April 3 has results broadly similar to Ipsos’s with Labor on 38 percent and the Coalition on 34 percent. Strangely it shows men are much more likely to support Labor than women (men 41 percent, women 35 percent) but this is so far out of whack with other polls that it may have the genders the wrong way around.

Morgan has a poll published on April 4, showing Labor on 39.5 percent and the Coalition on 33.0 percent, and a two-party-preferred lead for Labor of 57:43. These seem to be on the high side for Labor.

Essential’s poll of April 4 shows some improvement in the Coalition’s primary vote. Like Ipsos, it reports separately on the “undecided” vote. If the “undecided” vote were to be allocated the same way as those who report a preference, it would indicate the Coalition’s support at 38.9 percent and Labor’s at 37.9 percent. Doing the same with their two-party-preferred estimate gives Labor a 53:47 lead. Both of these estimates show significantly higher support for the Coalition than Newspoll, Resolve or Ipsos.

Can we trust the polls this time?

The ABC’s Casey Briggs – the fellow who has given us clear no-nonsense graphical data on Coronavirus cases over the last two years – has an article With election 2022 nearly upon us, can we actually trust the opinion polls this time?. He explains how in 2019 there was a bias in polls by major polling companies that resulted in their overestimating Labor’s support (by about 2.8 percentage points) and under-estimating the Coalition’s support, (by about 2.4 percentage points). That was because they were using a poorly structured sample, that did not adequately cover people with less education, who tend to be stronger supporters of the Coalition.

Also, in 2019 media commentators tended to put too much faith in the polls, ignoring the mathematically inescapable two to three percent margin of error in polls of 1000 to 2000 people.

Briggs reports that some polling companies, including Newspoll and Essential, have improved their sample weights. He reports on the performance of Newspoll in predicting the recent South Australian election. It slightly overestimated both the Coalition and Labor primary vote, while underestimating the vote for “others”, but its two-party-preferred estimate was spot on. (For reasons to do with name recognition and ease of recall, even the best designed polls have a bias towards over-estimating support for large and well-known parties, and to under-estimating support for small parties and independents.)

The website linked above has a link to a ten-minute video explanation by Casey Briggs, in his characteristically clear style.

How Australians interpret the budget: it’s about helping Morrison win the election

Essential’s regular fortnightly poll has a set of questions around economic issues, mainly about how well the budget has addressed cost-of-living pressures. Cost-of-living is nominated as the most important economic issue by 61 percent of respondents.

Unlike other polls that simply ask which party is best able to handle the economy, which almost always puts the Coalition ahead of Labor, this poll addresses six specific economic issues – cost of living, housing affordability, government debt, wage growth, unemployment and interest rates. Only on reducing government debt does the Coalition come out clearly ahead. On cost-of-living, housing affordability and wage growth, Labor is clearly ahead. On other issues there is little difference in people’s perception of the parties.

Understandably many people are undecided about how the budget will affect their own or the nation’s fortunes. Around half of respondents, however, believe that the budget will “place unnecessary burdens on future generations” and “create long-term problems that will need to be fixed in the future”.

The final question is about the objective of the budget: 44 percent believe it is about “helping the Australian economy recover and building it over the long term”, while 56 percent believe it is about “helping the Coalition win the next federal election”. On this last question there is a significant partisan difference: almost two-thirds of Coalition supporters believe the budget is about helping the economy.