The pandemic

Worldwide

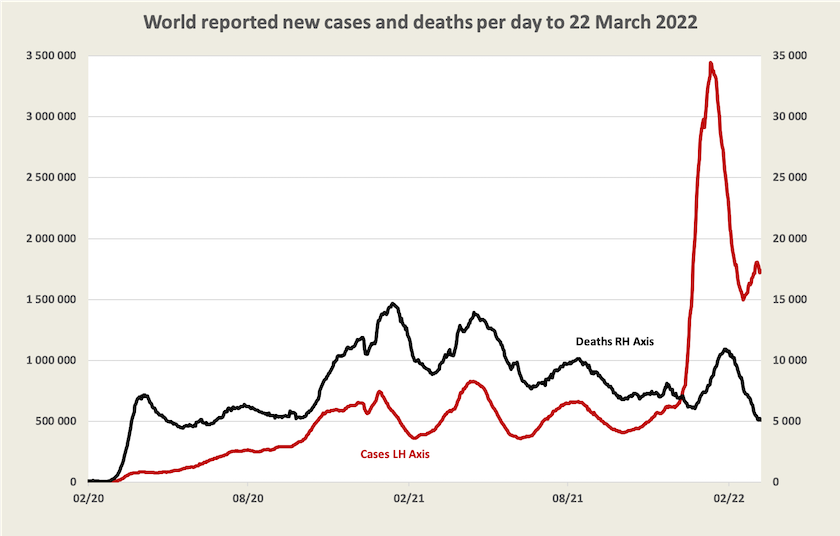

Worldwide recorded cases are rising but recorded deaths are falling.[1]

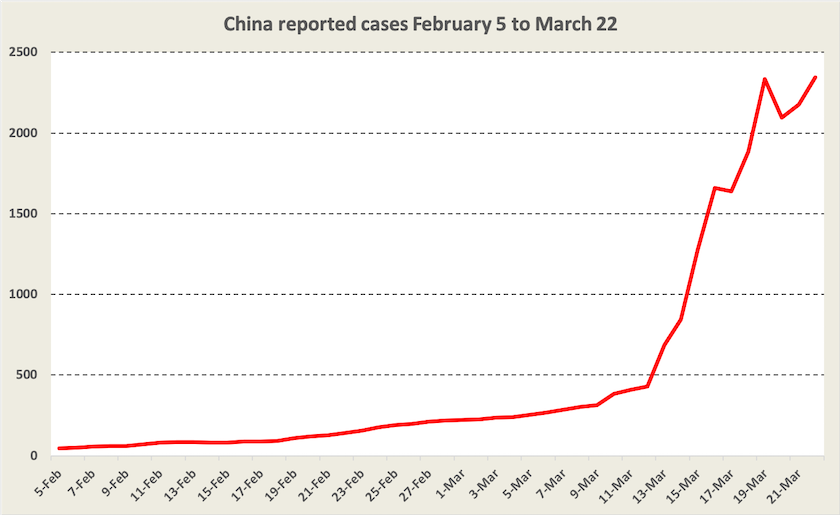

China is still trying to pursue a zero-Covid strategy. But, as shown on the graph below, its cases are rising steeply.[2] The growth over the last few days is more linear than exponential, but we should not expect to see smooth growth in a country adopting suppression approaches in specific regions as cases break out. If an exponential curve is fitted to this data, the doubling time is now around 8 days, suggesting that at this rate almost the whole population could be infected by the end of July. It could develop into a short-term but serious economic problem, not just for China, but for the whole world in view of the extent to which China is integrated with the world economy.

1. Even if deaths are reasonably accurately recorded (in some countries deaths are fudged for political reasons) case numbers are generally understated because of under-reporting, under-testing and the presence of asymptomatic cases. In its March 22 epidemiological update, the WHO warns that many countries are dropping their testing requirements and therefore reducing the number of cases being detected. ↩

2. Updating from last week. An exponential curve fitted on this graph shows an exponential function of y = 33.532 e0.0839x, where x is the number of days since February 5. The coefficient of correlation, R, is 0.963. If even the trend over the last 46 days is continued, the whole country could be infected within 5 months. ↩

Australia

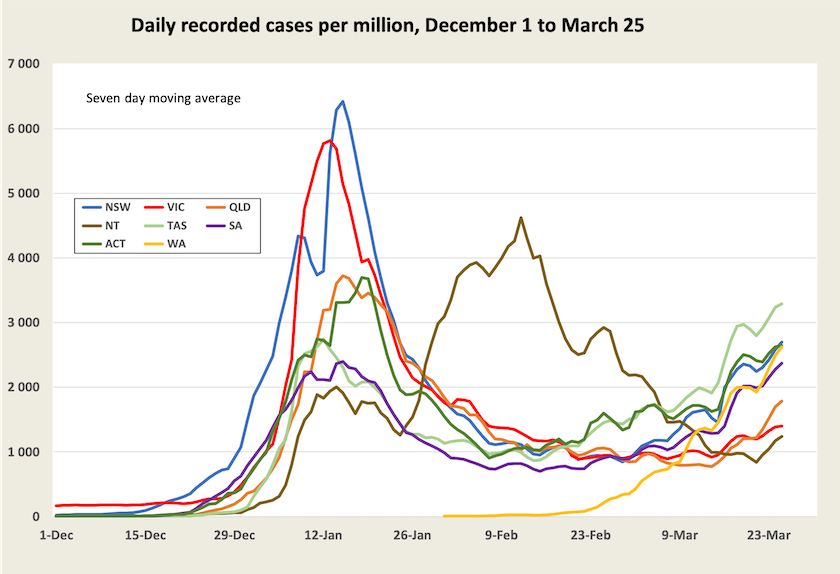

Cases are rising in all states and territories.

On the most recent Coronacast – Wasn’t the peak meant to be in January? – Norman Swan explains that this BA.2 variant is highly infectious, and that the virus will continue to manifest itself in waves, dismissing any notion that it’s settling down to a comparatively benign pattern.

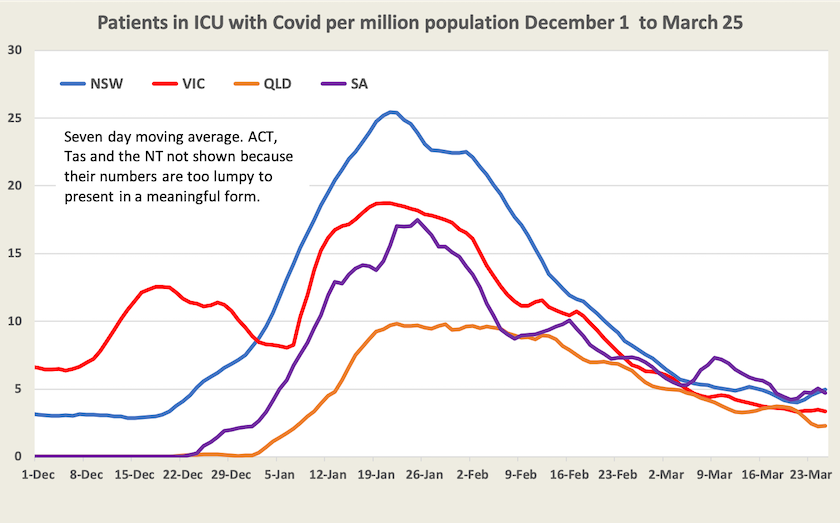

The number of patients in ICU, an indicator of the load on hospitals, is no longer falling, and could be expected to rise in the next couple of weeks.

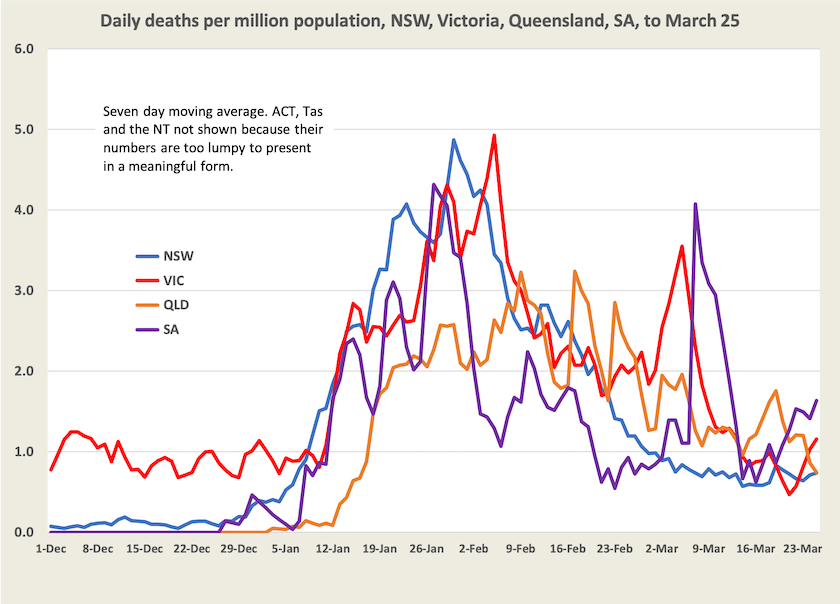

The number of deaths is no longer falling. The recent South Australia spike results from a recording of 23 deaths on one day, Monday March 7. This is almost certainly a result of official records catching up. In view of the importance of the state’s Covid-19 response in the election (did South Australia open up too early?), it is possible that such an administrative convenience may have had some effect on the perception of the seriousness of the situation; 23 deaths in one day is a big number.

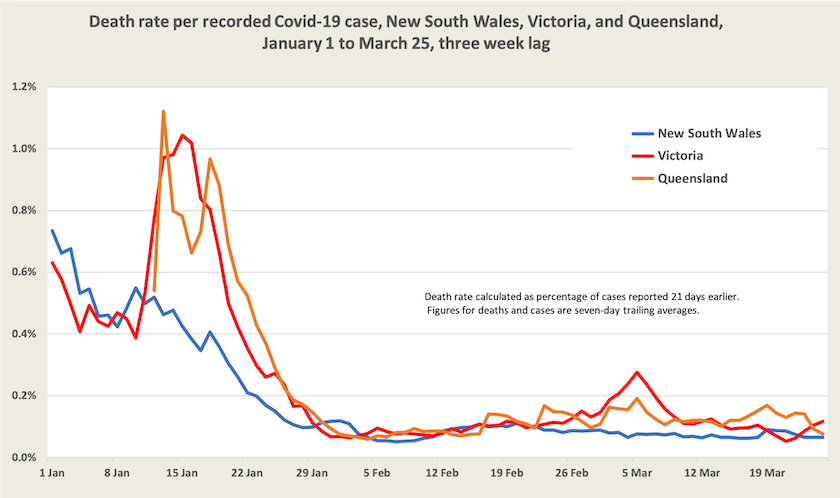

The number of deaths per recorded case, however, an indicator of personal risk, remains low, at about 0.1 percent or 1 in 1000. The curve below covers only the three largest states where numbers are large enough to even out.

Vaccination

Australia seems to be experiencing the same pattern as many other countries with this sub-variant of Omicron – high case numbers and a low death rate. This is in spite of a low third-dose vaccination cover – 49 percent, compared with cover between 55 and 70 percent in most other “developed” countries.

Third-dose cover ranges from a low 42 percent in Queensland, to a high 59 percent in the ACT, but these state and territory figures cover over significant variations within states. Drawing on Victorian state health department data, the ABC’s Leanne Wong and Ashleigh Barraclough have produced a map of third-dose coverage by local government area in Victoria. It is particularly low in northwest Melbourne, and not much higher in western Melbourne, the regions that were disproportionately represented in earlier outbreaks.

Those aged 65 or older and certain others will be offered a fourth dose of vaccine, possibly as part of a regular annual or six-month immunisation program, similar to the established influenza immunization program. This will be useful in terms of personal safety. It could be even better if it’s within a public health policy to prevent the spread of highly infectious respiratory diseases. A comprehensive program would require the provision of sick leave pay to casual workers, special provisions for others who cannot work from home, and a change in the “soldier on” culture that sees something heroic in people turning up to workplaces with highly infectious illnesses – a practice reinforced by untrusting employers’ resistance to working from home and their insistence that people get sick certificates (easily forgeable) to cover short absences from the workplace.