Australia’s enfeebled economy

Alan Kohler on our structural weaknesses

No doubt the budget will include handouts to help people deal with higher gasoline and food prices. To the extent that these price spikes result from wars, floods and Covid-19 supply line disruptions, the handouts will be useful, but they will not address the fundamental problem that real wages cannot grow in a structurally weak economy where there is almost zero growth in labour productivity.

In the first of a two-part 12-minute series on the ABC’s 730 program – Cost of living pressures spiralling – Alan Kohler discusses with other economists present policy options for the Commonwealth in dealing with inflation, and they’re not attractive. Although both monetary and fiscal settings have put plenty of money into the economy, wages are not budging while prices are rising. Tighter monetary policy – a lift in interest rates – may help stem inflation but would hurt heavily-indebted households even more than inflation.

The second part of the series – What are the risks facing the RBA in raising interest rates? – covers the inevitability of an increase in interest rates: the Reserve Bank has had to abandon its promise that its record low rates will hold until 2024. That will be hard on heavily-indebted households.

These two programs are about the consequences of 26 years of Commonwealth economic policy (20 of those years with Coalition governments) that has been obsessed with fiscal indicators (debt and deficits) while almost entirely neglecting structural reform. To its credit the Howard government had two structural reform achievements – the GST and independence for the Reserve Bank – but it undid its good work through capital gains tax changes that encouraged speculation over long-term investment, and that set the scene for ongoing housing price inflation and a huge accumulation of personal debt. The Rudd-Gillard government tried to reform taxes, but lost its nerve in the face of hysterical opposition from mining lobbies. It also introduced a carbon price, a market-based mechanism to help restructure our energy economy, but the Abbott government abolished it. Since then the National Party and mining lobbies have successfully thwarted even the most modest government attempts to deal with climate change, to the extent of forcing a prime minister out of office.

Australia’s part in sleepwalking into a climate catastrophe

The media has understandably focussed on one part of UN Secretary-General Antonino Guterres’ speech to The Economist sustainability summit – the part where he calls out Australia as one of the “holdouts” that have not announced meaningful emissions reductions by 2030.

His speech lists the fine promises made in Glasgow at the COP 26 gathering, contrasting their 2050 aspirations with their modest 2030 commitments. To keep warming under 1.5 degrees requires a 45 percent reduction in global emissions by 2030, and the world is not on track to meet it: in fact emissions are increasing. “We are sleepwalking into a climate catastrophe”.

He has particularly hard words about coal:

Those in the private sector still financing coal must be held to account. Their support for coal not only could cost the world its climate goals. It’s a stupid investment – leading to billions in stranded assets.

Also, particularly relevant to Australia, about gas:

And it’s time to end fossil fuel subsidies and stop the expansion of oil and gas exploration.

Carbon credits, falling faster than the Russian rouble

Carbon credits are an important part of a market-based approach to reducing carbon emissions. They allow firms time to adjust in industries that will necessarily have a major task in achieving net zero emissions. They’re a transient, rather than a permanent, approach to dealing with climate change, and to be effective they should become scarcer and more expensive over time.

But the Morrison government has been letting the value of carbon credits fall – by allowing the market for credits to be flooded, and by issuing them for worthless projects.

Writing in the Saturday Paper Mike Seccombe explains how energy minister Taylor has allowed holders of carbon credits, valued at about $12 a tonne (the government’s contracted price), to sell their credits on the open market: Angus Taylor’s $3.5 billion carbon blunder. Seccombe points out that by doing so, the market for credits has become much more liquid, making it easier for big polluters to meet their obligations through buying credits rather than reducing their own emissions.

The other problem is that many carbon credits have been issued for projects that do nothing to reduce emissions. They can be issued to firms that capture and store carbon. They can be issued to landholders to plant trees, to sequester carbon in the soil, or even not to clear land they would otherwise have cleared (reminiscent of Joseph Heller’s farcical account in Catch 22, of American farmers earning fortunes through being paid not to plant crops). On the ABC’s Breakfast program Andrew Macintosh, former chair of the Emissions Reduction Assurance Committee, explains how Australia is wasting billions on cheap carbon credits. Farmers are even being paid for not clearing land that they never intended to clear anyway, or for growing trees in arid lands where trees will struggle to survive. Macintosh is particularly annoyed that the contracts the government enters into are so shrouded in secrecy, making it nearly impossible for the public, who fund these offset schemes and reasonably expect them to help reduce emissions, to scrutinize their effectiveness. He also points to conflicts of interest built into the scheme for issuing carbon credits.

In both cases the beneficiaries are the firms that act as carbon traders, and the losers are the taxpayers.

Another Morrison government scam to do with climate change is its $1.2 billion investment in hydrogen technology. Hydrogen, when burned, is not polluting – its only residue is water – but unless it is produced from green sources, the processes to make it can result in high emissions: see the roundup of February 19. The Australia Institute has produced a short video clip Fueling net zero fraud with false solutions explaining the deceit involved in using fossil fuels to make hydrogen and claiming it to be “green”.

Corporate taxes – an economist’s case for reform

In recent years, while most countries have been reducing their rates of corporate tax, Australia’s rate has stayed at 30 percent, which is now high in comparison with other countries. Business lobby groups, and Liberal Party politicians, keep reminding us of this comparison, while rarely mentioning that because of dividend imputation, an initiative of the Hawke-Keating government designed to encourage Australians to invest in Australian companies, the actual rate of tax paid by Australian owners of Australian companies is quite low.[1]

The Tax and Transfer Policy Institute at ANU’s Crawford School of Public policy has produced a major analytical paper Corporate income taxation in Australia: theory, current practice and future policy directions, briefly described in a press release Corporate equity allowance can fix tax system.

It lists a number of problems with current corporate taxes, including policies that tend to favour debt finance over equity finance, leading to a bias that overstates the cost of equity and makes firms too heavily debt-financed.

Its approach is to see taxes from the standpoint of the corporation, as if the corporation is literally a “corpus” – a body with its own interests. Such a corporation sees a “normal” return on investment as a cost of doing business, and not as a “profit” to be taxed, and it opportunistically takes advantage of economically unjustified breaks, such as the tax deductibility of interest and depreciation rates that do not correspond to life-cycle costs.

The authors advocate a tax-system known as Allowance for Corporate Equity, which allows for “normal” profits, calculated as a competitive market’s return on equity investment, to be considered as a tax deduction, and taxes to be applied only on profits above that level – “economic profits” in the language of economists. (This may appear to be radical, but it is routinely used in bodies that set prices in sectors prone to monopoly profits.) The authors claim, with strong arguments, that our present tax laws have over-encouraged investment in the mining and finance sectors, while relatively discouraging investment in sectors with more modest returns, thus contributing to an inadequately diversified economy.

Understandably, it is critical of imputation, because imputation encourages firms to distribute dividends rather than to re-invest them, and it contributes to a “home bias”. It’s a work rooted in economics rather than in political economy.

1. The actual tax paid by investors depends on the firm’s dividend payout. If a firm pays 50 percent of its profits as dividends – which is roughly the long-term average for Australian public companies – the effective tax rate is 15 percent (30% X 0.5). If it pays 70 percent of its profits as dividends the effective tax rate is only 9 percent (30% X 0.3). This means corporate profits are picked up in investors’ personal taxes. ↩

Our roads paved with pork fat

Elections bring forth promises of road projects – a long-neglected missing link in a freeway or an extension to a rail network. Often, however, the projects are minor – straightening a dangerous bit of road, a new roundabout, an extra lane in an urban road.

It is hardly surprising that such politically-determined transport funding does not line up with the nation’s most pressing transport needs.

The Grattan Institute recommends three changes to the Commonwealth’s legislation directing its transport funding – the National Land Transport ACT 2014. These are:

- to restrict funding to roads and rails on the National Land Transport Network – essentially those providing national and interstate links;

- to prohibit federal funding for any project costing $100 million or more unless it has been subject to publicly-released benefit-cost evaluation by Infrastructure Australia;

- to prevent ministers from making changes to National Land Transport Network before Infrastructure Australia has evaluated the national significance of any such changes.

The analysis supporting these recommendations – Roundabouts, overpasses, and carparks: hauling the federal government back to its proper role in transport projects by Marion Terrill – looks at the allocation of transport funding, and election promises in recent years. It’s a story of funding allocation to marginal seats of projects large and small, and of Commonwealth involvement in projects entirely lacking in national significance. It’s also a story of discretionary funding going disproportionally to Queensland and New South Wales, the states with most marginal electorates in 2019 and now in 2022.

The report is not entirely critical of the Commonwealth. When funding criteria are objective and transparent, as in the Black Spot Program and the Roads to Recovery Program (both of which programs involve a great deal of state government discretion), funding tends to be even-handed electorally, while directing funds to rural areas where needs are greatest.

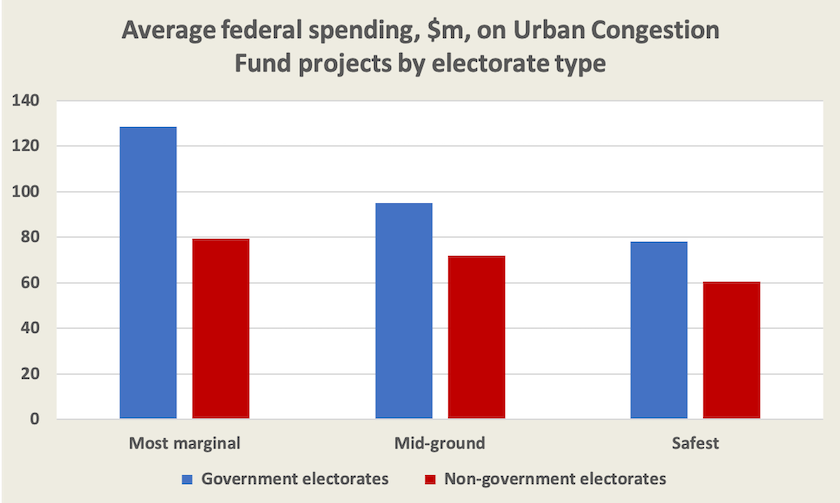

But when funding is discretionary and opaque, most notably in the Urban Congestion Fund (remember those car parks?), allocation is highly partisan, as shown in the graph below, reproduced from Grattan’s data. If there were no partisan bias in those allocations, we would reasonably expect all those bars to be much the same height.

The conclusion: if you want congestion improved shift to a marginal Coalition electorate. (Would a Labor Government resist the temptation to mirror the Coalition’s corruption?)