Australian politics

South Australia – another instalment in the Coalition’s long slow death

An annoying media habit is to say for every election that it will be a tight contest, as ABC and other journalists were predicting on the eve of the South Australia election, even though it was clear from polls and from the government’s shaky parliamentary position that Labor was bound to win.

The result should have come as no surprise. The Coalition is not representative of urban Australia, and with 1.4 million of 1.8 million South Australians living in Adelaide, South Australia is the most urbanized state in Australia – so urbanized that it has never supported a viable branch of the National Party.

One person who claims to have been surprised is former premier Mike Rann, who gave his interpretation of the results on ABC’s AM: Former Premier “surprised” by size of Labor win in SA. (6 minutes) He was surprised that electors gave the Liberals only one term. His interpretation of the Liberals’ loss is mainly about its handling of the latest wave of the pandemic. Although the government handled Covid-19 well for most of the last two years, in December, at the urging of the “business community” and against the advice of public health officials, they opened up just as the Omicron wave was breaking. He also believes the Liberals ran a poor campaign. Wisely they didn’t invite Morrison to help them out – his presence would have been toxic – but they invited John Howard, whose involvement reminded people that the Liberal Party is stuck in another era.

A question hanging over the result is whether it has any federal implications. Michelle Grattan believes that it broke the assumption that the pandemic favoured incumbent governments, but was that ever a strong assumption?

There are at least two other aspects that do have federal implications.

First, is the reasonably high accuracy of opinion polls, as Adrian Beaumont points out in The Conversation. For a few weeks polls had been predicting a Labor win. They tightened as the election approached, but the final Newspoll had Labor on 41 percent (election result 40.3 percent) and the Liberals on 38 percent (election result 35.9 percent). Other polls, Beaumont points out, were even closer for the Liberal vote. Liberal Party strategists have been dismissing federal Labor’s high poll numbers by recalling that the polls before the 2019 election were predicting a win for Labor. They now have to face the possibility that the polls may be right.[1]

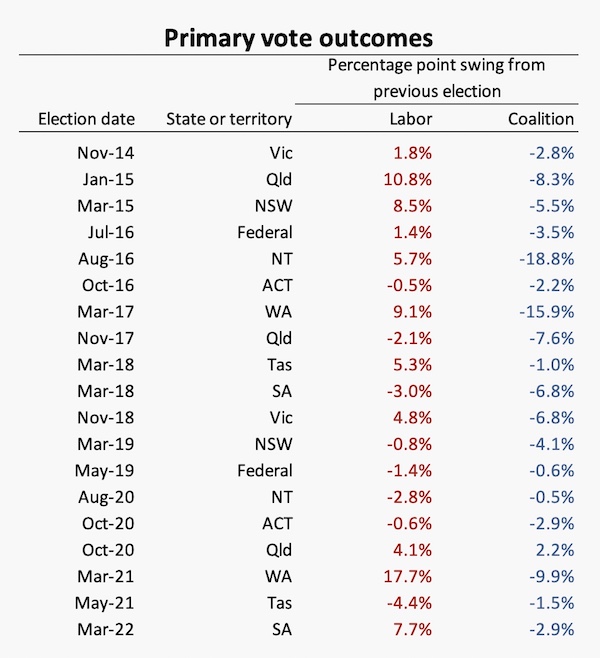

Second, and more worrying for the Liberal Party and their National Party coalition partner, is that this is the 18th of the last 19 elections, state and federal, in which the Coalition has lost support. This loss of support is shown in the table below which shows the change in Labor and Coalition primary vote for each election.

Note that this is not about two-party outcomes. For example, in South Australia in 2018 the Coalition lost primary support (mainly to the short-lived SA Best), but it won the election. Similarly the 2020 Queensland election was the only election in which the Coalition’s primary vote increased, but this was associated with a crash in support for One Nation. Labor won that election.

Could this slide in Coalition support have something to do with their “small government” ideology? For example one significant issue in South Australia has been ambulance ramping: putting money into hospitals was a strong Labor policy, while the Coalition’s priority was for a football stadium.

At first sight, in view of successive opinion polls confirming the importance of health care among voters’ concerns, the Coalition’s football priority looks plain stupid, but it has logic in the Liberal Party’s “small government” ideology. A stadium is a once-off outlay, while any boost to health services has to be ongoing. At both state and national levels the Coalition is reluctant to do anything outside the defence budget that commits governments to more ongoing expenditure.

Most economists can point to the reasons, to do with multiple aspects of market failure, justifying public expenditure on health care, funded by higher taxes if necessary. But few economists can point to reasons why scarce public funds should be directed to a sport stadium. Sure, people like spectator sports, but they also like beer and rock concerts: these needs can all be met by the market.

To the Liberal Party, however, all public expenditure is waste. It is only in the private sector that real value is created: “businesses and individuals – not government – are the true creators of wealth and employment”, to quote from the party’s sacred document titled Our beliefs. If all public spending is wasteful – simply something that governments must do to get re-elected – then a football stadium is no less a waste than an expanded health system.[2]

Liberal governments do reluctantly fund Medicare, the ABC, public schools and so on, but less out of conviction that these are things that the market cannot provide, or cannot provide so well, than as a realization that unless they do fund these things they have little hope of gaining or holding office.

In the wash-up to the South Australian elections there are the usual recriminations and rationalizations – poor election tactics, bad behaviour by some members of parliament, unfortunate timing in relation to the pandemic. They may all have some influence, but such more-or-less random events cannot explain why the party has lost support in 18 out of 19 elections. Maybe its “small government” economics, or its accommodation in its ranks of hard-right social conservatives who use the terms “Christian” and “family”, may have something to do with it.

Daniel Keane of ABC’s Adelaide News provides some history of South Australian politics, and some insight on policy issues are manifest in factional divisions in the state Liberal Party: SA election 2022: the Playmander, the Rannslide and the roots of Liberal implosion.

Those who wish to follow election counting in South Australia or to analyse the results can find up-to-date data on Antony Green’s site on the ABC, or on the South Australian Electoral Commission’s site.

1. In 2019 the outcome was actually within the margin of error of most polls. ↩

2. This is essentially a description of the neoliberal ideology known as “public choice” theory. ↩

2022 election polling

William Bowe’s Poll Bludger has election polls that, at first sight, appear to give wildly different estimates of parties’ two-party preference support. One is a Morgan poll that shows Labor leading by a whopping 16 percent on a TPP basis, compared with the latest Essential poll that shows a 4 percent TPP lead for Labor.

These disparate figures illustrate the caution one must take in interpreting any TPP estimate. There are just too many assumptions and accumulated sampling errors in going from primary votes to TPP figures, but these TPP figures are attractive media bait.

Morgan’s primary voting figures are 31.0 percent for the Coalition and 37.5 percent for Labor, lower for both parties than the most recent Newspoll (35 percent, 41 percent), but revealing the same roughly 6 percent gap in support. Essential by contrast has Labor and the Coalition level pegging on 37 percent – showing no gap in the parties’ support. This difference could be explained by the extremes of sampling errors. They may also be explained by Essential’s practice of separately recording “undecided voters” – 7 percent in this most recent poll. That classification includes those who haven’t engaged at all with the political process, through to those who have made up their minds about voting against Morrison, but haven’t decided whether to vote Labor, Green or independent.

Issues polls

Essential

Essential’s fortnightly poll has the usual questions on people’s approval of Albanese and Morrison, and on who would make the better prime minister. No surprises here: on approval Albanese now enjoys positive approval (i.e. approval > disapproval), and Morrison suffers negative approval (disapproval > approval); Morrison still enjoys a tiny lead as preferred prime minister; and the trends are in Albanese’s favour.

It has a question on how we rate the federal government’s response to recent flooding: we’re not impressed but not rushing to condemn the government either. Coalition supporters believe the government has done a reasonably good job, while Labor supporters think they have done a poor job.

A more revealing set of questions relates to climate change, with specific reference to the floods. Almost two thirds of respondents (65 percent) agree that “given climate change is happening the government needs to do more to prepare for extreme weather events”; 57 percent agree that “if there isn’t significant action on climate change soon, we can expect flooding in Australia to be even worse in the future”; and 53 percent agree that “If we’re serious about reducing the future impact of floods, Australia needs to replace coal with renewable energy as soon as possible”. On these same questions, while about 20 percent “neither agree nor disagree”, very few respondents actually disagree. There are some age-related differences: older people are a little less likely to agree on the second and third of these statements, and there are significant (and dismally predictable) differences based on voting intention. In all, however, we are convinced that climate change is real and that the government should be doing more about it.

Another set of questions relates to people’s assessment of the truth of their sources of information. It reveals us to be a reasonably skeptical lot. We’re most trusting of “friends and family”, followed by “mainstream media”. Politicians and media feed rate poorly. Women are more skeptical than men, but older people tend to be more trusting of mainstream media and of politicians. Coalition voters are generally more trusting of all sources, including politicians, than Labor voters.

A related set of questions asks respondents if they think there should be laws about truth in political advertising, and about stopping the spread of disinformation. There is quite high support of such regulation, particularly among older people.

Our high level of trust in “friends and family” underscores the importance of political conversation in all settings.

JWS Research True Issues

The JWS True Issues poll, aims to reveal the issues Australians care about, and how well they believe the Commonwealth government is addressing these issues. When unprompted, respondents mention health care, the environment and the economy as the top three issues. When prompted to respond by choosing from a list of possible concerns, “cost of living” comes to the top.

When asked how well the Commonwealth is performing in various areas of concern, the top marks go to “defence, security and terrorism”, “business and industry”, “mining and resources”, while the lowest marks go to “cost of living”, “the environment and climate change”, and “housing and interest rates”. In all 21 areas surveyed, people’s perception of the government’s performance over the last 12 months has fallen.

The position of “cost of living” – top of people’s concerns, bottom on the government’s performance, gives some hint of what will be in next week’s budget, and in the election campaign.

Respondents were asked about how well different organizations and groups have performed. After many years of perceived improvement, there has been a fall in our perceptions of government from mid-2020 – the period in which the pandemic took hold. That fall has been sharpest for the Commonwealth, less sharp for state governments, and only slight for local governments.

The poll also has some questions on people’s engagement with political issues and the extent to which they have already made up their mind on how they will vote. Unsurprisingly, those who are less interested in the election are more likely to be undecided in their voting attention.

The most important issues that people raise in the election context are “the environment and climate change”, “hospitals, healthcare and ageing” and “economic management” (whatever that means). “Cost of living” and “Housing and interest rates” are of lower rank, in positions 3 and 4, suggesting that although they are major concerns, they may not see the government having a great deal of control over them. Not everything we worry about is an election issue.

Morgan on trust

Roy Morgan has a poll on trust and distrust, both of government and of individuals. Trust in government (level of government not specified) has been falling for the last year from already low levels. The poll also has some findings about mistrust of people in government and of other prominent political figures. Of the ten Australian politicians listed, Morrison is the least trusted, followed by another nine conservative politicians. When they add Clive Palmer, Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump for comparative reference points, Palmer tops the list as least trusted, but Morrison, Dutton, Joyce and Hanson are all less trusted than Putin.