Australi’s enfeebled economy

Australia’s structural weaknesses

In every election we hear the same old refrain about the Coalition’s economic competence, a claim that rests on their approach to fiscal management, guided by an obsession with balancing the cash budget.

Fiscal management is only a tiny aspect of economic policy however: it’s about bookkeeping. The hard work in economic management is in attending to our economic structure, and that has been largely neglected by Coalition governments.

On Late Night Live Satyajit Das, in a 19-minute session, describes some of the structural weaknesses in the Australian economy: Australia's economic choices: post-pandemic trends. The pandemic has revealed some fundamental economic problems that we’ve been ignoring, the most important of which is deepening inequality. The fiscal and monetary measures employed in response to the pandemic may have worked in macroeconomic terms, but they have worsened our economic disparities, particularly as they affect the fortunes of those who work in human service industries – the “uberized” economy to use Adams’ and Das’s term.

Inflation and low wage growth – problems that usually don’t appear together – will be difficult for any government to deal with, because they cannot be handled by tweaking a few monetary and fiscal variables. They are structural in origin: inflation has resulted from a monetary stimulus to demand while many costs on the supply side have risen, and our workforce lacks the skills that can justify high wages. There is a massive mismatch in the skills we have and the skills needed in a globally competitive economy. Immigration won’t be our saviour – who wants to come and live in a country where housing is so ridiculously expensive?

The hard slog of structural reform does not appeal to our politicians, however. It doesn’t make for a flow of political announcements. “Structural change takes a long time … that’s why they prefer things like national security, culture, identity and character” because politicians don’t have to do very much to deal with these issues, or at least to be seen to be dealing with them.

Das is author of Fortune’s Fool: Australia’s Choices part of the Monash University Press In the national interestseries.

Gasoline prices

Australia is one of a handful of countries where the poorer you are, the more you need to own and use a car. You may have to work odd shifts when public transport does not run; you may live out in the far-flung suburbs where housing is affordable but public transport doesn’t reach; you may live in the outback where the nearest shop and medical practice is hundreds of kilometres distant along a rough corrugated road. And you probably own an old vehicle: data from the Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Ecnomics reveal that a car made in 2000 or earlier has an average fuel consumption of 11.4 litres/100km, while a car made during or after 2011 has a fuel consumption of 10.3 litres/100km. Various hybrids on the market have fuel consumption between 4 and 5 litres/100 km, and owners of electric cars probably don’t have to think of gasoline, but there aren’t many charging stations in the outback.

Cheap gasoline, pity about the suspension

So it’s not surprising that people have been shocked by pump prices of $2.20 for 91 octane gasoline, and $2.40 for 98 octane needed in high-compression engines. But is cutting the 44 cent excise the best way to bring relief to people burdened by high prices for gasoline and other goods affected by gasoline and dieseline prices?

As Michael Bradley of the Australian Automobile Association explained on ABC Breakfast on Monday, that 44 cents funds transport infrastructure, and after many years of tightly-constrained government budgets, and high rates of population growth, our transport infrastructure is in poor shape: Cut to fuel excise would cause long term infrastructure pain. (7 minutes) That’s because, since 2017-18, there has been a close relationship between Commonwealth and state transport taxes collected and expenditure on roads.

Bradley could have gone on to make the point that although the rate of excise is linked to the CPI, there has been less revenue collected as vehicle fuel efficiency standards improve. He could also have pointed out that Australia has very low taxes on gasoline and dieseline by world standards. That may be one reason Australia has almost the worst car fuel economy standards in the OECD, pipped only by the USA.

Although there is a strident anti-road lobby (usually comprising well-off people who can afford to live in inner urban regions) there is a case for spending motor vehicle taxes on transport infrastructure, and there is a separate case for having an additional layer of tax on gasoline and dieseline to cover the cost of global warming – a classic case of charging for externalities. Cutting excise would work against both objectives.

In the short term a more equitable and economically efficient approach may be for the Commonwealth to increase excise and spend the extra revenue to help the states reduce motor vehicle registration fees – a tax that’s completely unrelated to road use or pollution. This would be particularly helpful for those who own cars but don’t drive them very far.

At the same time there should be more incentives for people to buy electric cars (although the fuel price rises in themselves provide a strong incentive). According to data from the International Energy Agency, Australia is a serious laggard in moving to electric vehicles. A by-product of more dependence on electric vehicles would be lessened dependence on countries like Saudi Arabia and Russia.

In the longer term the most equitable path may lie in settlement patterns that reduce everybody’s need to travel.

The gun dealer’s defence of our energy industry

In 2012 a deranged man shot and killed 20 children and 6 adults at the Sandy Hook School in Connecticut. This year the manufacturer of the Bushmaster XM15-E2S semiautomatic rifle has finally agreed to accept some level of responsibility for the killings, and will pay the families $US73 million. The gun-dealer’s defence – “I have no responsibility for the consequences of what I sell” – did not hold up.

In the context of our energy exports – coal, gas, and uranium – Ian Lowe and Jeremy Moss discuss the responsibility of our energy companies for the consequences of what they sell. In the case of fossil fuels these consequences are their contribution to global warming (“Scope 3” emissions), and for uranium there are consequences of diversion to weapon production, nuclear accidents, and problems associated with long-term storage. Even if we attend to all our domestic sources of greenhouse gas emissions, the emissions from customers in other countries burning our fuel would still be twice our present domestic emissions.

Their 34-minute discussion – The gun dealer’s defence – on nukes, fossil fuels, and Australia – was chaired by the ABC’s Natasha Mitchell at the Adelaide Writers’ Festival.

The discussion is wide-ranging. They discuss the economics of nuclear power as a source of clean energy (it’s prohibitively expensive), the ethics of firms quitting coal mining (worse than ineffective when another company buys the mines), the notion that we should sell our thermal coal to keep the lights on in poor countries (we actually sell most of our thermal coal to Japan and Korea), and the supposed national benefits of fossil-fuel mining (they’re piddling).

A theme common to both fossil fuels and uranium is that under present arrangements, companies bear very little of the costs of the consequences of their actions – cleaning up old mine sites, dealing with nuclear accidents, uranium getting into the wrong hands. These costs are inevitably borne by taxpayers.

The books that took Lowe and Moss to the festival are Lowe’s Long Half-Life: The Nuclear Industry in Australiaand Moss’s Carbon Justice: The scandal of Australia's biggest contribution to climate change.

(Perhaps we can simply kick the problem of clean-up costs down the road, at least for coal mines supplying our power stations. Scott Morrison has said that our coal-fired stations should run as long as they possibly can.)

Housing – waiting for the bubble to deflate

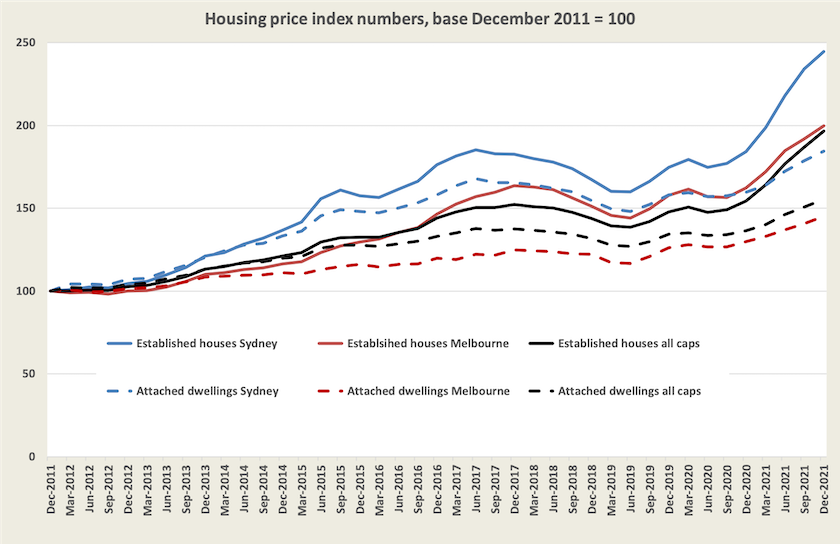

ABS figures on housing prices – residential property price indexes for eight capital cities – were released on Tuesday, covering the period up to December 2021. These are not as timely as the CoreLogic figures, but they do separate out houses and units (“attached dwellings”), and they use a methodology that disregards the effects of changing quality (called “hedonic adjustment”).

The short story is that in the ten years from December 2011 to December 2021 the price of houses in Australia has doubled, rising by 97 percent, while prices generally (the CPI) rose by 22 percent, and wages rose by 25 percent.

The graph below shows this movement nationally, and for Sydney and Melbourne, our two largest cities. It also shows, in dotted lines, the price movement for units (“attached units”). I have chosen this period because it corresponds to the period in which interest rates have been falling: the first post-GFC interest rate reduction was in November 2011.

By 2017 some sanity appeared to be returning to the housing market, but by 2019 prices started rising again, pausing only a little for the pandemic (the prospect of mass deaths puts rather a dampener on housing demand). But then, as the Reserve Bank pushed the base interest rate below 1.0 percent, the market took off again, particularly in Sydney.

The dotted lines for units tell a less bullish story. Prices of units initially rose along with houses, but they have gone their separate ways. Nationally unit prices have risen by 56 percent, and in Melbourne by only 45 percent. Although a block of apartments takes longer to build that a free-standing house, when they come on the market they can do so in a rush, when other apartment blocks are also being completed. Also, particularly in Sydney where the state government has been lax in enforcing construction standards, apartments may be becoming less attractive for buyers.

As yet there is still capital gain in apartments, but when the housing prices collapse it will probably be most noticeable in Melbourne’s apartment towers.

Put it on the never-never

One so-called “financial innovation” of recent years has been buy-now-pay-later (BNPL) schemes, whereby for transactions of $1500 or less, one can pay for a purchase in four interest-free instalments – one at the time of purchase, the other three at two-weekly intervals. The business model works in part by retailers bearing part of the cost – in other words by passing on the cost to all customers – and by levying fees on those who miss or are late in making payments.

As many Australians struggle with BNPL debt, Choice has joined with other consumer groups in calling for regulation of the industry, endorsing a statement by 11 consumer organizations in 9 countries. BNPL is able to exploit weaknesses in consumer legislation, allowing it to skirt around consumer protection laws. Because there is no interest charged, a BNPL liability is technically not a “loan”.

Choice’s statement provides some disturbing data about BNPL debt accumulated by Australians: 15 percent of BNPL users have missed or been late on payment, and 78 percent of those “have experienced financial hardship as a result of buy now, pay later fees, including taking out an additional loan or forgoing household essentials”.