Australia's enfeebled economy

Albanese’s speech: Labor’s economic agenda

Albanese’s speech on economic policy on Wednesday – Time to advance – should put paid to any notion that Labor is soft on economic management. Its theme has echoes of the Hawke-Keating reforms of the 1980s – economic policies to undertake the structural reform that the Coalition has neglected over its eight years in office.

He mentions the manifestations of our poor economic performance – low business investment leading to low labour productivity, leading in turn to low wage growth.

He encapsulates Labor’s economic policy in “five pillars” to restore economic growth. The first, unsurprisingly, is around realizing the competitive potential of our renewable energy resources. The second and related pillar is about further processing of mineral resources, particularly lithium, as part of a general renaissance in manufacturing, in part to serve our infrastructure and mining industry needs. The third is about skills, investing in both TAFE and universities. The fourth is investment in child care to allow more people, mainly women, to participate in the paid workforce. (It’s a pity he didn’t mention the long-term economic benefits of investment in early childhood education.) The fifth is about infrastructure: he describes himself as an “infrastructure nerd”. Infrastructure is something a government provides to support the national economy; it isn’t a vehicle to provide electoral boondoggles in marginal seats.

Macroeconomics 1 in two minutes

The media pays a great deal of attention to each month’s unemployment statistics and to each quarter’s national accounts, but the longer-term performance of the economy gets comparatively scant attention. The slow deterioration of our nation’s economic performance is far more consequential than month-to-month or quarter-to-quarter movements in economic indicators, but it is not newsworthy. Also, it runs counter to the uncritically accepted story that the economy is in good hands with a Coalition government.

While most journalists have been excited by the latest national accounts showing the largest GDP growth since 1976, Alan Kohler provides a longer-term perspective in a two-minute clip, presenting trends in key economic indicators over the last 30 years. In this period economic growth has slowed, wages growth has slowed, and productivity, the basis for sustainable income growth, has slowed.

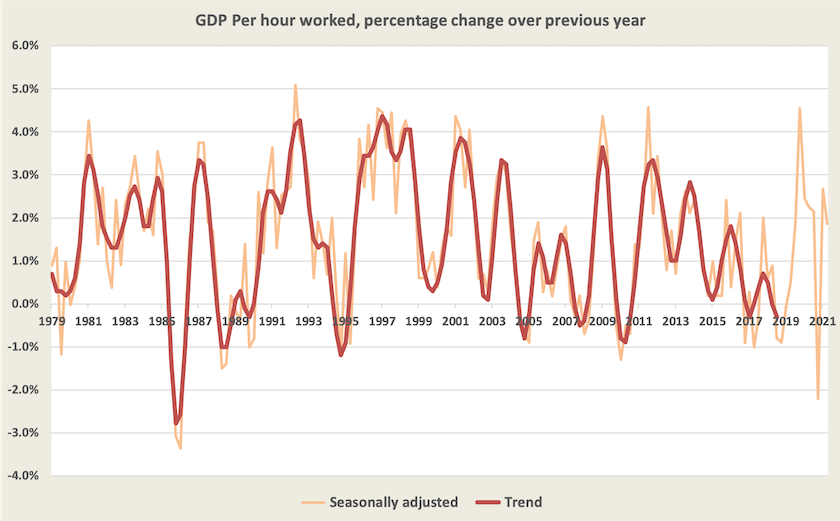

The graph below, taken from the same national accounts release that has so excited the media, shows the basic indicator of Australia’s productivity – GDP per hour worked. The orange line is the seasonally-adjusted figure but it makes little sense over the last two years. As Kohler points out, national accounts figures over the period of the pandemic have been extremely volatile. The red line is the trend, up to the point when the pandemic started to render trend estimates meaningless.

Most notable is the fall in productivity over the last decade.

Kohler tracks the deterioration in economic performance over three successive decades – the 1990s, the 2000s and the 2010s. He attributes the fall in productivity in the 2010s to a fall in business investment. The explanation he offers for this lack of investment, in spite of low interest rates, is “the absence of a coherent energy policy”.

Kohler discreetly mentions that “the 2010s decade began with the death of bipartisanship on global warming”. It’s a pity that as an ABC commentator he has to use such fudged non-partisan language. It was Tony Abbott, first as opposition leader and then as prime minister, with the backing of the fossil fuel industry, and with a little help from the Greens, who wrecked any chance of Australia having a responsible energy policy. The same political forces, with their influence through the National Party and a few climate-change deniers in the Liberal Party, are still holding Australia back.

Coming back to those productivity figures, from 1979 (when the ABS started collecting data in its current form) up to 2013, productivity was growing at 1.6 percent a year. That’s enough to give reasonably firm real wage growth of one to two percent a year. From 2013 to 2019 – since the Coalition took over the reins – productivity growth has averaged 0.9 percent a year, and, as the graph shows, has fallen over their time in office.

This is not some statistical artefact: it is the outcome when a government has limited its economic management to one concern, the fiscal balance, and has ignored the far more important need to have policies to deal with our economic structure.

Is our economic recovery simply a short-lived bout of pent-up demand?

Have you ever noticed that when the ABC wants to interview someone about the state of small business, they are most likely to turn to a hairdresser?

Economist Richard Holden, in a Conversation article – Vital signs: Australia’s hairdressing-led economic recovery can’t last – queries whether a spending-based recovery can endure. Speculating on the upcoming budget he writes “The big question is what will be needed to drive the economy in the years ahead. It will require more than a rebound in restaurant meals and haircuts”. In line with many other economists he stresses that if we want to get the economy back on a path of growth, we have to engage with the hard work of improving our productivity.

A similar analysis is given by Ross Gittins: It will take more than faith to keep the economy growing. He takes us through the relationship between wages, productivity, inflation, spending and growth – fairly standard macroeconomics fare. The Australian economy’s productivity performance has been poor. That would usually mean there is no capacity for real wages to rise, but because the economy has been well-stimulated with monetary and fiscal measures, contributing to high corporate profits, there is capacity for employers to lift wages without resulting in inflation. That should ensure that the pickup in consumer spending is not just a once-off – the worn-out appliance we had to replace, the house repairs we couldn’t get done during the pandemic, the haircut we’ve been waiting for.

The cost of floods

As the clean-up following the floods gets under way and people assess their losses, three problems associated with insurance have come to the fore.

First, there are many people who, put off by high premiums, or by the natural tendency to procrastinate, carried no insurance.

Second, many people when they lodge their claims will find that they have been under-insured. Even people who carefully calculated the cost of replacing their buildings will find that the floods have stimulated demand-led price rises for skills and building materials, and that building standards may have been made more stringent.

Third, many will find that if they go on to re-build, insurers will have hiked their premiums to prohibitive levels in response to the floods.

Writing in The Conversation – Victims of NSW and Queensland floods have lodged 60,000 claims, but too many are underinsured. Here’s a better way – three academics from the University of Queensland suggest a scheme whereby the government essentially acts as a re-insurer for the insurers. They point to examples in Europe where such schemes already operate. While re-insurance is a normal aspect of private insurance markets, the benefit of the scheme the authors propose is that if the government is underwriting insurers it has an incentive to reduce its liabilities by making sure its regulations on land release and building standards, and its decisions on infrastructure, give it an incentive to prevent situations that will result in high claims.

The Commonwealth is already offering cyclone damage re-insurance for people in far north Queensland, but this does not fit the authors’ model, because it has no incentives for the Commonwealth or local governments to do anything to reduce risk, while it carries the moral hazard of subsidised insurance. Its purpose was to shore up votes in vulnerable Coalition seats rather than to implement an economically responsible risk-sharing scheme.

The authors touch on a general problem with private insurance. Insurers are good at covering people for misfortunes that occur with predictable patterns such as petty theft, car accidents, lightning strikes and so on. But when it comes to events that do not fit statistical risk models, insurers do all they can to limit their exposure. In fact insurers distinguish between “risk” and “uncertainty”: they thrive on risk but they cannot handle uncertainty.

As a consequence, while people can easily find policies to cover minor events, such as loss of household contents, when it comes to events that can be truly ruinous policies just aren’t available. Insurers offer policies that cover repair or replacement up to a cap of $X thousand dollars, but for the open-ended costs above that $X thousand, customers are left to their own resources.

Most people can recover from a loss of $50 000 or $100 000, but few can recover from complete loss of their house or business. So-called “insurers” make their living from covering small losses, such as house contents, while leaving people exposed to huge open-ended losses. It’s a cruel hoax to call policies that leave people exposed to devastating losses “insurance”.

Climate change, with its uncertainties, adds to the category of events that no longer fit into a statistical risk model.

Crispin Hull notes that in times past such events were largely confined to the far north, but as we have seen over the last two weeks they are occurring in more settled areas: The Gladstone Lines move south. Opportunistic workarounds such as the Commonwealth’s scheme for far north Queensland (his reference to the “Gladstone Lines”) become too expensive when they start to affect big cities.

There is a strong case, based in conventional economics, for nationalizing those aspects of insurance that cannot fit into normal risk models. Collectively we have voted for governments that have failed to deal with climate change; we should therefore be willing to pay collectively through our taxes to compensate those who suffer the consequences of our irresponsible and short-term political choices and to pay for climate change mitigation.

The pandemic has reversed progress in women’s wages

Using ABS data on weekly earnings, the McKell Institute points out that over 2021, while average real (CPI – adjusted) wages have fallen, women’s wages have fallen faster than men’s wages.

They have used state-based data to show that the difference has been worst in Victoria (male + 1.3%, female – 1.4%, difference – 2.7%), while at the other end of the spectrum, in Western Australia, women have done relatively better than men (male – 3.2%, female – 1.0%, difference + 2.2%).

McKell does not explain reasons for these state differences, but it is notable that Victoria was the state most severely hit by Covid-19, while in Western Australia life carried on essentially pandemic-free. A glance across their table suggests that the difference has related to the impact of Covid-19.

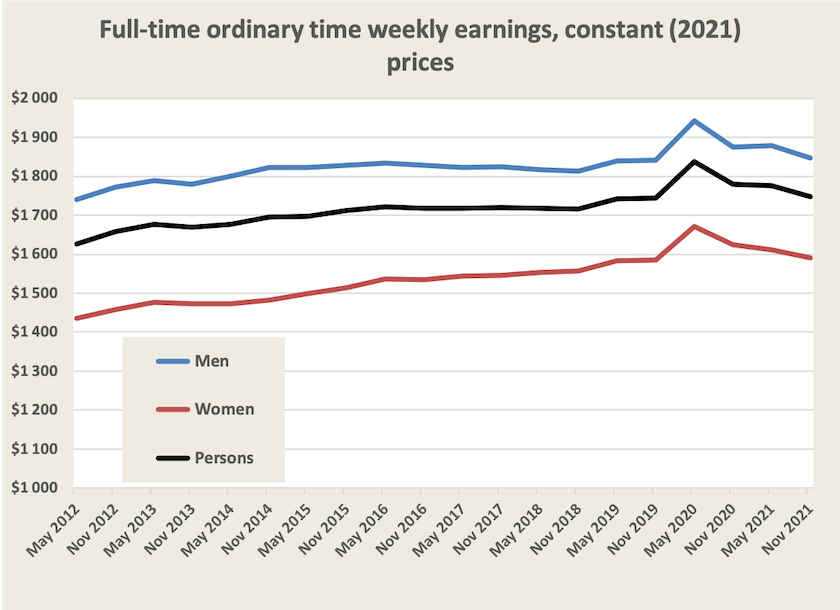

To put these figures into a broader context, the graph below shows men’s and women’s real wages since 2012 (the start date for the ABS’s current wages series).

This reveals some notable features:

- wages generally flatlined from 2015 to 2019 – men’s wages fell while women’s wages rose;

- the bump in 2020 associated with rising unemployment and the effect of “Jobkeeper”– in part this bump is explained by the classification of “Jobkeeper” payments, and in part by the fact that when unemployment rises, it’s often the poorest-paid workers who lose their jobs, thereby pushing up the average wage;

- the fall in men’s and women’s wages in 2021, as noted by the McKell work, but they are still (just) above pre-pandemic levels.

We can cautiously conclude that the pandemic, and the public policy responses to the pandemic, have probably been responsible for a slowing in progress towards closing the gap between men’s and women’s wages.