Other economics

How the labour market works

If you want to understand terms such as the “labour force”, the “participation rate”, “unemployment” and so on you can sit through a few Economics lectures.

Or you can read Gareth Hutchens’ neat explanation – The unemployment rate is falling quickly. This 'special formula' explains why – on the ABC website. He explains, with illustrations from Australian experience over the last twenty years, the relationship between population growth and unemployment.

He doesn’t present the fallacious argument that immigration costs Australian jobs, but he does explain how the Covid-19 restrictions have led to a very tight labour market and therefore a low rate of unemployment.

Real wages are going backwards

In a recent tweet, Frydenberg said that when Labor lost power in September 2013, real (inflation-adjusted) wages were falling.

In fact they were falling, if you consider one quarter’s wage cost index and one quarter’s consumer price index.

That would earn a “resubmit – with some meaningful analysis” on a first-year economics assignment. It therefore shouldn’t be beyond the capacity of a federal treasurer with a Law and an Economics degree from Monash, a Master of Philosophy from Oxford, and a Masters in Public Administration from Harvard’s Kennedy School.

ABC business reporter Gareth Hutchens has done that basic analysis, comparing real wages during the last few quarters of Labor’s term in office, and what has probably been the Coalition’s last few quarters in office. Frydenberg’s figure is meaningless. Wages are growing, but the value of your pay packet has deteriorated again.

Hutchens’ main point is that wage growth has been weak for the last seven years, almost the Coalition’s entire time in office.

The real test for a government’s economic performance is its ability to sustain real wage growth over an extended period, which can occur only if there is meaningful policy attention to structural policy.

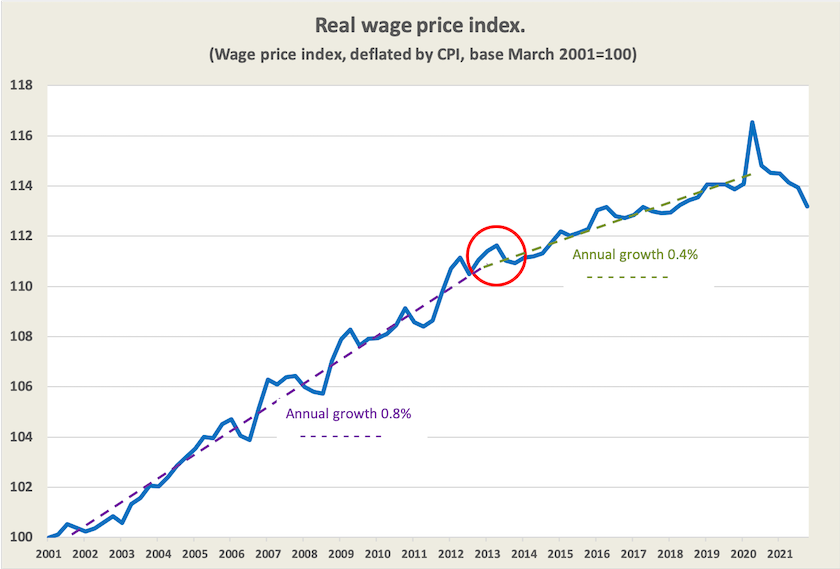

The graph below shows the real (CPI-deflated) wage price index since 2001.

The dip to which Frydenberg refers, in the September 2013 quarter, is shown in the red circle. But what stands out is a sharp drop in the rate of wage increases from 2013: note the break in the dotted trend lines. Until 2013, through to the period of the Rudd-Gillard-Rudd Government, real wages were growing about 0.8 percent a year. Since then, until March 2020 (it would be unfair to include the last two years), they have grown at only 0.4 percent a year.

On that ground the entire Coalition earns a “fail” grade.

Graphs and articles by economists only confirm what people experience. Drawing on figures from the February Resolve Strategic survey, Sydney Morning Herald’s David Crowe reports that only 12 percent of workers believe their real incomes will rise this year, and that they are losing confidence in Australia’s economic outlook: Voters worry about falling wages, back lower migrant intake.

Private and public schools

On last weekend’s Saturday Extra Geradine Doogue interviewed Tom Greenwell and Chris Bonnor on what the Gonski report achieved. (20 minutes) Greenwell and Bonnor, both experienced teachers, are authors of Waiting for Gonski: how Australia failed its schools.

It is ten years since businessperson David Gonski and his team presented a report to the Commonwealth Government Review of School Funding, which became known as the “Gonski Review”. It highlighted Australia’s declining performance in school education, and the growing gap between the educational outcomes of disadvantaged children and their more privileged peers. It recommended a model to target public funding to disadvantaged students based on a minimum resource standard for all schools, with additional loadings based on students’ needs.

Politically it was received with enthusiasm at the time, but governments did not implement its reforms, and over the last ten years our general school education outcomes and the gap between advantaged and disadvantaged students have worsened. We now have what may be the most socially segregated school system in the OECD – a segregation sustained by funding formulae favouring elite private schools and disadvantaging the poorest schools in the state system.

There is something defeatist in the interview. Discussion on the program was about the reforms having “failed”, and much was in the passive voice, without agency: for example “a lot wasn’t addressed”, or “simply hasn’t happened”, as if the proposed reforms were poorly crafted and as if there was some inevitability in their failure. The reality is that although Tony Abbott went into the 2013 election promising to implement the Gonski reforms, he deliberately broke his promise and continued with – in fact strengthened – the old inequitable system.

A reader has brought to our attention a report by Trevor Cobbold of Save our Schools, Labor’s Gonski Model: The National Plan for School Improvement, that covers much the same ground as the Saturday Extra session, while naming the politicians and lobbyists who, mostly through greed and partly through poor political judgement made sure that reforms were never implemented. As he writes:

… the potential of the NPSI was undermined by several major flaws, some of which were self-inflicted by the Labor Government and some which were forced on it by the Liberal Opposition’s ruthless campaign against the model and resistance by private school organisations.

Has all that money going to private schools achieved anything? Writing in The Conversation Sally Larsen and Alexander Forbes of the University of New England assure us that going to private school won’t make a difference to your kid’s academic scores.