(Mainly Australian) politics

Religion in politics: by their deeds you will know them

How many of us have heard about the University of Divinity?

It’s a multi-faith theological collegiate university, with Anglican, Baptist, Catholic, Coptic, Lutheran, Salvation Army, and Uniting Church colleges.

Robyn Whitaker of the University of Divinity reminds us of a basic aspect of mainstream Christian moral theology when she writes in The Conversation Morrison’s Christian empathy needs to be about more than just prayer – it requires action, too.

She also reminds us of what “forgiveness” means in the Christian tradition (and in many other moral traditions). “In the Christian tradition, no apology can insist on forgiveness, and seeking forgiveness for harm done requires repentance, acts of restitution, and attempts to address injustice.” That contrasts strongly with the admonition that when people are wronged, individually or collectively, they should just “move on”.

How we react to politicians’lies

Writing in The Conversation Ullrich Fisher and Toby Pike of the University of Western Australia summarize research about our response to politicians’ lies: We know politicians lie – but do we care?

It turns out that we do care. Their experiments involved giving people statements made by politicians, and then showing them factchecking findings revealing them to be lies. (Presumably they had no difficulty in finding such statements.) They found that when Australian voters believe politicians are lying, their feelings and voting intentions change.

They found a difference between Australian and American voters, however. When we learn our politicians are lying we are more likely to change our support and even our vote, while Americans tend to accept that lying is just part of the democratic process. (Unfortunately the authors do not even speculate on the reasons for this difference.)

In a related vein Rob Harris, Europe correspondent for The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age, writes that Morrison’s breaking of his promise to establish an integrity commission could prove to be politically costly.

The politics of trade unionism

There was an industrial dispute on Sydney’s rail network on Monday, leading to a one-day shutdown and reduced services on other days. On a 5-minute segment of the ABC’s 730 Report Ewin Hannan, a journalist who specializes in labour relations, described how the state transport minister had intervened to use a minor and sanctioned industrial dispute that would cause no inconvenience, as an excuse to shut down rail services. Who will win NSW's train shutdown blame game?. (Subsequently there has been a great deal of recrimination about just who was to blame.)

Even though the dispute was a state one, and the inconvenience resulted not from union action but from blundering aggression by a state government, Morrison was quick to weigh in, warning listeners on his favourite 2GB radio station that Sydney’s disruption is a warning of the industrial chaos that will result if we are reckless enough to elect a Labor government.

Is union-bashing a winning strategy for Morrison? A survey conducted in January by the Pew Research Center revealed that 58 percent of US adults believe that the long-term decline in union membership has been bad for the country. There are predictable partisan differences: 71 percent of Democrats agree with the proposition, but a sizeable 40 percent of Republicans agree. It is notable in both America and Australia that union membership remains strongest in sectors that have borne most hardship in coping with the pandemic, particularly health care and transport.

The angry mob

On the ABC’s Roundtable program, Julian Morrow interviewed three political scientists – Barbara Perry from Ontario Tech University’s Centre on Hate, Bias and Extremism, Josh Roose from Deakin University, and Yasha Monk from Johns Hopkins University – about Canada’s “Freedom Convoy”, asking if they, and the similar movements in Australia, pose a threat to democracy.

Where did our history curriculum go wrong?

Although there are some multinational movements, they do not believe the protests have been arranged by some central organizing body. Rather they spread through emulation and imitation in what Perry describes as “an amorphous movement”. Local organizers draw on a “reservoir of anger”, ostensibly stemming from pandemic restrictions, but there are deeper resentments to do with people losing jobs, a growing realization that the economic system is stacked against them, and a feeling that the prevailing economic and social systems treat them with disrespect. It is easy for far-right extremists and conspiracy theorists to hitch a ride on these movements.

Ben Rich of the Curtin University Extremism Research Network, writing in Eureka Street, sees these movements as manifestations of “the failure of online civil discourse and a rise of radical movements and networks fixated on issues of divisive culture war”. He describes the attraction of the “fighting identity” to those who feel let down by the world – “a world where the abundance and opportunities of the past seem increasingly distant and out of reach”: Fighting identities: polarisation, nihilism, and the collapse of online discourse.

Dominic O’Sullivan of Charles Sturt University, writing in The Conversation, looks at the demonstrations from the perspective of powers delegated to police to deal with demonstrations and minor acts of civil disobedience: The Wellington protest is testing police independence and public tolerance – are there lessons from Canada’s crackdown? He notes that in the cities where demonstrators have been active the public tend to regard them as an irritating nuisance, rather than as a political movement. (Could this be because they carry no clear message?)

Australian opinion polls

After a drought three new polls came last week.

First, the two-party figures – the most referred to but also the most subject to error. All point to a Labor lead over the Coalition, but there is a wide variation: Essential: 52:48, Resolve Strategic 53:47, Roy Morgan 57:43.[1] That is a lead for Labor somewhere between 4 and 14 points.

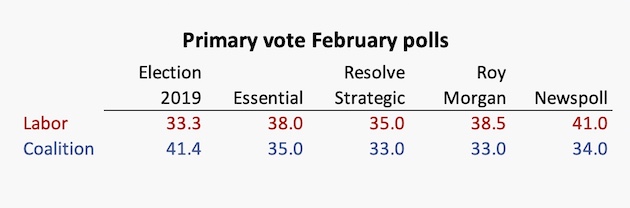

There is less spread in the primary vote, as shown in the table below, which also includes the Newspoll (covered last week).

While there is a 6-point range in estimates for Labor support, there is only a 2-point range in estimates for Coalition support. The message from the polls is a little fuzzy about Labor’s support, but the Coalition is definitely in trouble. If 41 percent of the vote got them a bare majority in the last election, there is not even a “narrow path to victory” on 34 percent support. Closing a 7 percent gap in 12 weeks would be a Herculean task.

A delve into the polls throws up many more figures, but disaggregations carry more error than gross figures. The polls consistently show a strong gender gap (women don’t like the Coalition), and a strong age gradient (older Australians remain strongly attached to the Coalition). Some polls have estimates for support for small parties, but mathematically such estimates are highly unreliable (polls work best for figures around 50 percent). William Bowe’s Poll Bludger has some cautious interpretation, as does Adrian Beaumont in The Conversation: Morrison’s ratings slump in Resolve and Essential polls; Liberals set to retain Willoughby.

There is a great deal of media attention paid to Morrison’s and Albanese’s approval/disapproval ratings, and on preferred prime minister ratings, but according to the Resolve Strategic poll, for 46 percent of people the factor with the greatest influence on their voting choice is “the party and their teams”, with “the party leaders” coming in at only 16 percent. “An issue or policy” likewise comes in at only 16 percent.

Essential’s other regular poll, its two-weekly Essential Report, covers a range of political issues to do with Morrison’s and Albanese’s performance. No surprises there. It has a few findings not covered in other polls:

On the question “In general, would you say that Australia is heading in the right direction or is it off on the wrong track?” men and older people are more likely to believe we’re on the right track than women and younger people;

In judging which party people would “most trust to build a relationship with China in Australia’s best interests?”, 37 percent nominate Labor while 28 percent nominate the Coalition. Older people put more faith in the Coalition, however. There is a related set of statements starting with the words “Australia’s relationship with China is …

There is a set of questions about our level of concern with the Russia-Ukraine conflict. No surprises: we’re concerned for a number of reasons.

[1] The 52:48 for Essential is based on their 49:45 2PP figure which does not include 6 percent undecided.↩