Pandemic politics

World

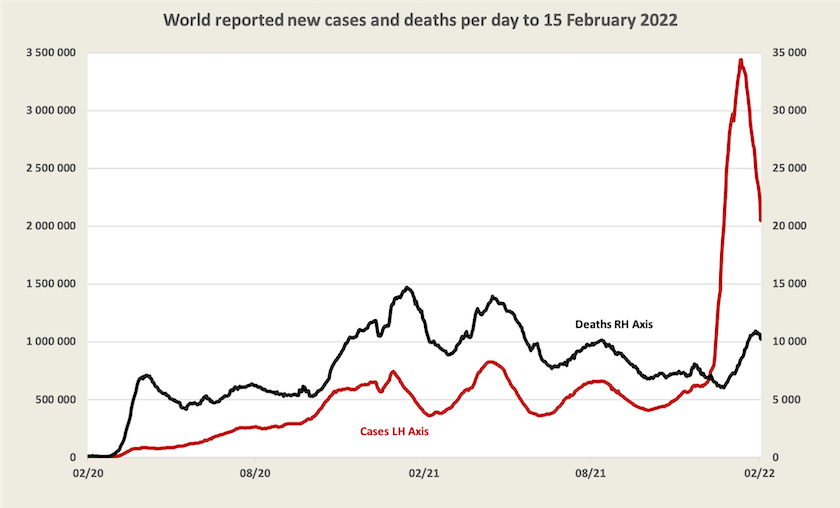

Worldwide, for those countries that keep records of deaths and cases, the Omicron wave is well past its peak and deaths seem to have peaked about a week ago. These observations are subject to the usual qualifications.[1]

Globally vaccination is about one percent up on last week: 64 percent of people have had at least one dose; 56 percent two doses, and 16 percent three doses. In the world’s poorest countries, however, only 11 percent of people have received even a first dose.

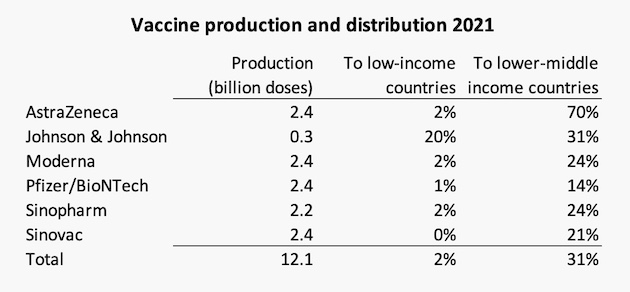

Amnesty International has been monitoring the distribution of vaccines to poor countries by pharmaceutical suppliers That data is consolidated in the table below.

Even if the WHO target of 70 percent vaccination by June is reached (a possibility at the present rate), it’s unlikely that Amnesty’s target of 50 percent vaccination of people in low and lower-middle income countries will be reached by then.

Australia

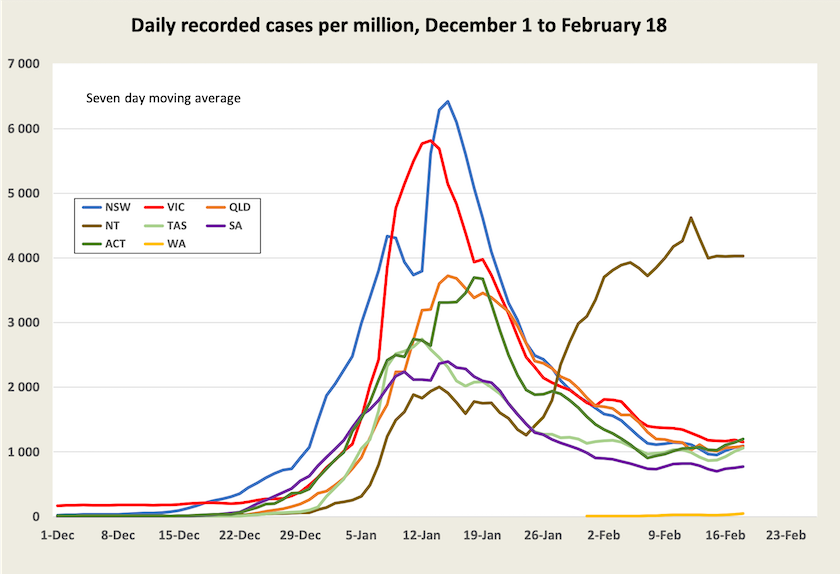

Cases – stabilising or possibly falling

In all states and territories, apart from the Northern Territory (where case numbers are very high), and Western Australia (where cases are on a strong exponential growth from a small base), daily recorded cases seem to be stabilising at around 1000 per million population.

On Friday’s Coronacast Norman Swan has some counterintuitive advice for Western Australia: it should open its border very soon, but maintain some public health measures, before vaccine immunity wanes. He also has a general warning for all of us about ventilation: there is still much to be done to improve ventilation in schools, public buildings and workplaces.

It is possible that although the number of actual cases may be falling, this fall is not evident as more cases are being recorded because of easier availability of rapid antigen tests, particularly in schools. Evidence that the virus is spreading less quickly is revealed in a decline in the positive rate for PCR tests, which in New South Wales has fallen from around 20 – 35 percent in mid-January to around 10 percent now. That’s still high, suggesting there are many undetected cases, but not as many as a month ago.

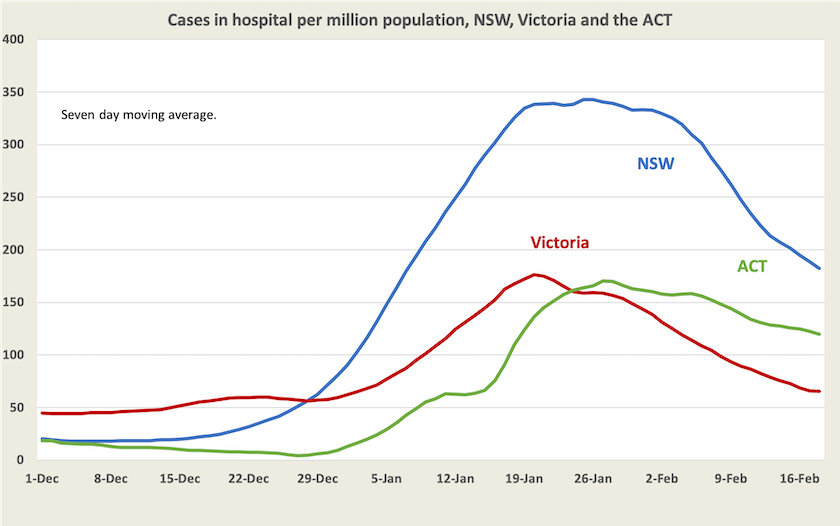

Hospitalizations – falling but still imposing a heavy load on the health system

These are shown on the graph below for New South Wales, Victoria and the ACT. [2] That is the proportion of people in hospital, not the proportion of people being admitted to hospital.

It’s a reasonably robust indicator of the stress Covid-19 imposes on the health system.

On last weekend’s Sunday Extra Tim Roxborough and Mayeta Clark ran a session on stresses in New South Wales hospitals: How Covid chokes a hospital (40 minutes). It’s anecdotal but it puts flesh on that graph. It’s a story of intense stress, burnout, and the mistakes people inevitably make when they have been working absurdly long hours, while in those long hours they cope with distressed and often angry patients seeking care.

Burnout and the distress and sense of personal failure when people realize they have made serious mistakes take their toll. The cost is borne not only by the individuals, many of whom give up their career in health care – a career for which they have invested years of hard study and apprenticeship, and a career which they have chosen out of a passion to do something for other people. As people quit, the stress on those who stay on worsens, leading to a destructive positive feedback loop of staff losses, more stress on remaining staff, contributing to more losses …. And the cost to the community is a degraded health system and the trashing of private and public investment in human capital.

Although they are real and tangible, few of these costs show up on government accounts. As nurses and other commentators on the program point out, state politicians who decided to make the hospital system bear the burden of relaxing restrictions for the sake of “the economy”, against the advice of public health experts, had either a callous attitude to health care workers – they’re only public sector employees – or a poor understanding of economics.

Deaths – still unacceptably high, but falling

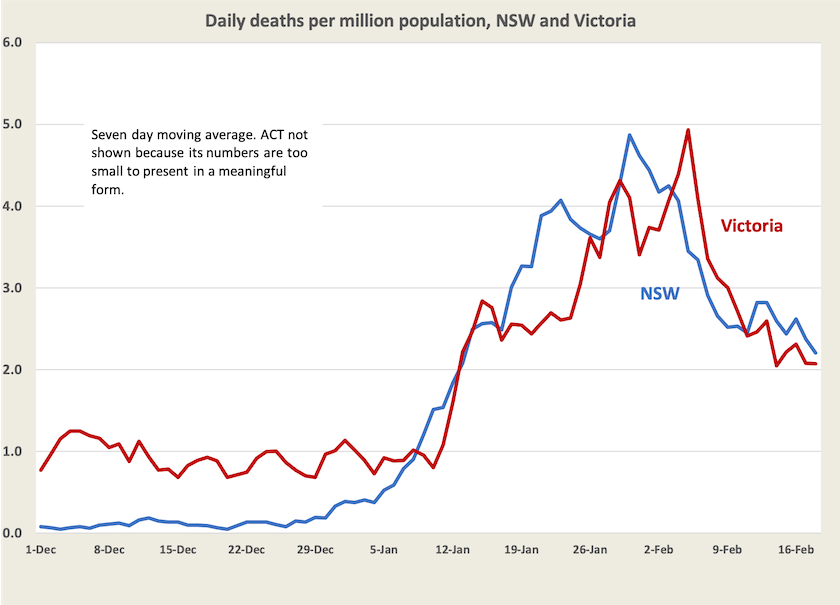

Deaths in New South Wales and Victoria have peaked. Because they occur about two weeks after admissions, they are yet to peak in other states and territories.

These death rates of two a day per million people are still extraordinarily high. They should continue to fall because they relate to a period when infections were running at about twice their current rate. But even a daily death rate of one per million would be high: nationally they would translate to around 9000 deaths a year, and a large number of cases of “long Covid”. To give some perspective on that figure every year about 160 000 Australians die of all causes: another 9000 is a significant increment. It’s about three times the number of deaths by suicide and eight times the number of road deaths, which are both matters of public policy concern.

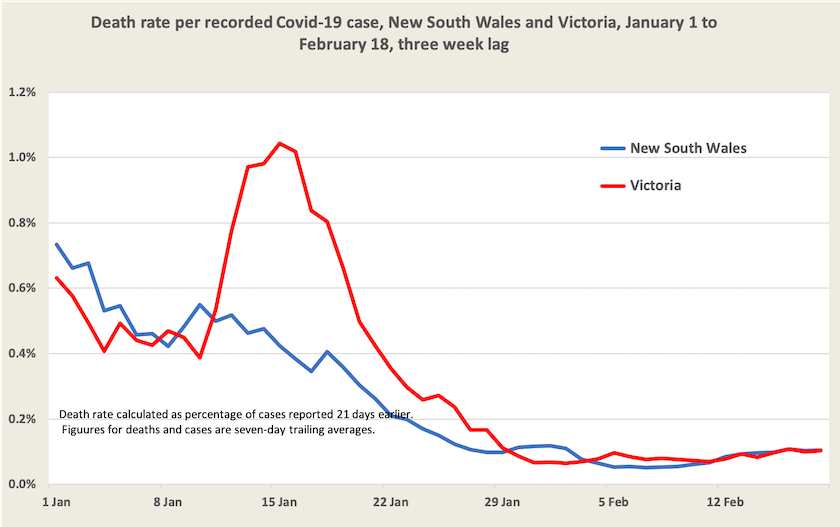

The case-specific death rate from this variant of Covid-19 – that is the chance that one who has been infected with Covid-19 dies, is about 0.1 percent, or 1 in 1000, as shown in the final graph.

This aligns with figures in the latest New South Wales weekly Covid-19 surveillance report, which, for the period 26 November to 29 January records 751 deaths from 803 104 cases, a death rate of 0.09 percent. The report provides additional detail on “severe outcomes” (ICU or death) according to vaccination status and age, confirming that older people are much more likely than younger people to suffer a serious illness and that vaccination, particularly three-dose vaccination, is highly effective in protecting against a severe outcome. To illustrate the combined effect, among those aged 60 or older, who have had three doses of vaccination, the rate of “severe outcomes” was 0.8 percent; for those with less than two effective doses the rate was 14.0 percent.

1. In almost all countries cases of Omicron would be under-reported, and in many “underdeveloped” countries neither cases nor deaths are well recorded. ↩

2. Juliette O’Brien and her colleagues provide data on hospitalization in all states, with warnings that different states have different definitions of what constitutes hospitalization. In all states and territories hospitalizations appear to have peaked, but later than in New South Wales and Victoria. ↩

Coping with Covid

The media has paid a great deal of attention to people’s loss of confidence in the federal government, revealed in a survey by Nicholas Biddle and his colleagues at the ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods.

That’s only one finding in its report Tracking wellbeing outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic (January 2022): Riding the Omicron wave. Because the loss of confidence aligns with other negative perceptions of the Morrison government’s performance it is hardly newsworthy.

The survey tracks our reaction to the waves of Covid-19. We were looking forward to it coming to an end until the Omicron wave came. Although few of us report having had a positive Covid-19 test result in this wave, 80 percent of us now believe we will be infected in the next few months.

Its finding on how people in different income groups are adjusting to Covid-19 is somewhat counterintuitive:

Household income is a strong predictor of the COVID-19 measures, with those in low- income households having a significantly and substantially lower expected likelihood of infection and lower testing rates than those in the middle-income category. However, those in low or high income households are no more or less likely to have needed/wanted a test but not been able to obtain one.

This contrasts with the general finding that the health and economic costs of Covid-19 have fallen disproportionately on the poor, but the survey is about people’s behaviour in apprehension of contracting Covid-19 and their fear or acceptance of its consequences. Also low-income households would include older stay-at-home households who are indeed at low risk.

Another general finding is that although we experienced more psychological distress and loneliness when the pandemic hit, particularly during the early lockdowns, those effects have subsided and do not appear to have worsened as Covid-19 has re-appeared in its variants.