Pandemic politics

World – Omicron has peaked, but we haven’t suppressed the virus

World figures – lots of cases, but not so many deaths

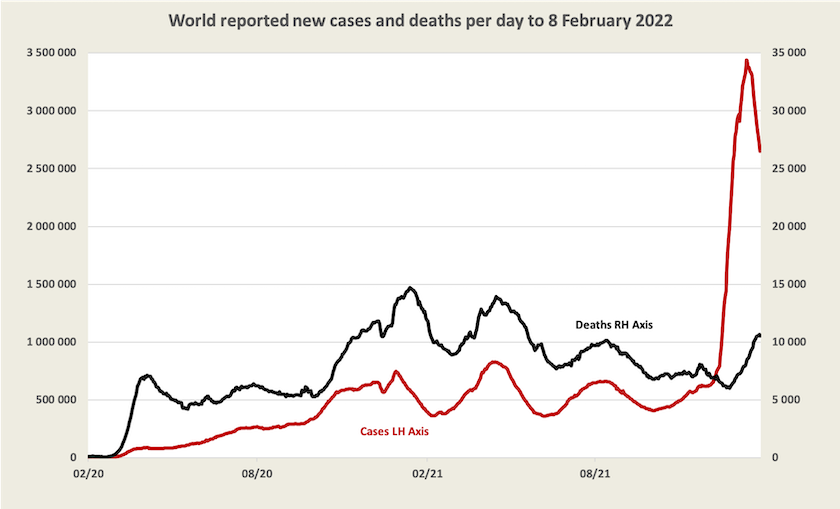

The graph below shows an update of cases and deaths, with the usual qualifications,[1] Recorded cases have peaked, and deaths, which lag by a few weeks, may be close to peaking.

The WHO weekly epidemiological update shows that this recent peak in cases has been concentrated in Europe, the USA and Brazil.

The pandemic could be over this year

That is, if vaccines, tests and treatments are made available to all people, according to UN Secretary-General António Guterres.

That would cost $US23 billion, of which so far less than $1 billion has been raised under the ACT-Accelerator program, the umbrella for COVAX and other initiatives.

A back-of-the-envelope calculation reveals that if that $23 billion were borne by the 950 million people living in the world’s 22 high-income “developed” countries, it would come to about $A35 a head – the price of three rapid antigen tests.

On the ABC’s The World Today Catherine Bennett and Tim Costello in his role as spokesperson for End Covid for all explain that although Australia has committed $500 million over the next few years to help other countries deal with Covid-19, the money is needed now. Australia should contribute $460 million straight away, a trivial amount compared with the economic cost of lockdowns and people’s withdrawal from commerce if the virus is not stopped. The epidemiology is straightforward: if we don’t help poorer countries we could get a variant that’s deadlier than Omicron. (Bennett and Costello’s segment is between 14:55 and 18:13 on Thursday’s The World Today.)

Worldwide vaccination progress is promising: 63 percent of people have had at least one dose; 55 percent two doses, and 15 percent three doses. In the world’s poorest countries, however, only 11 percent of people have received even a first dose. First-dose vaccination rates are even lower in Africa’s two largest countries, Nigeria (4 percent) and Ethiopia (7 percent).

In almost all countries cases of Omicron would be under-reported, and in many “underdeveloped” countries neither cases nor deaths are well recorded.↩

Covid-19 in Australia

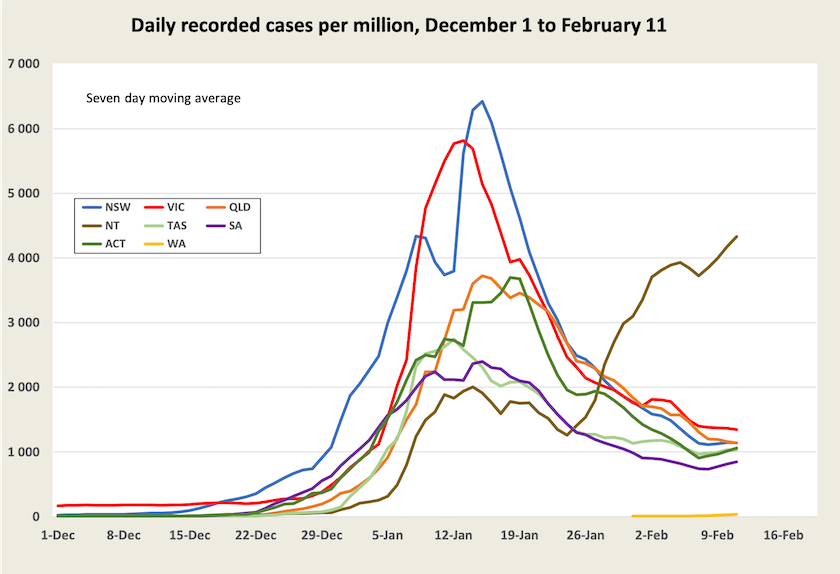

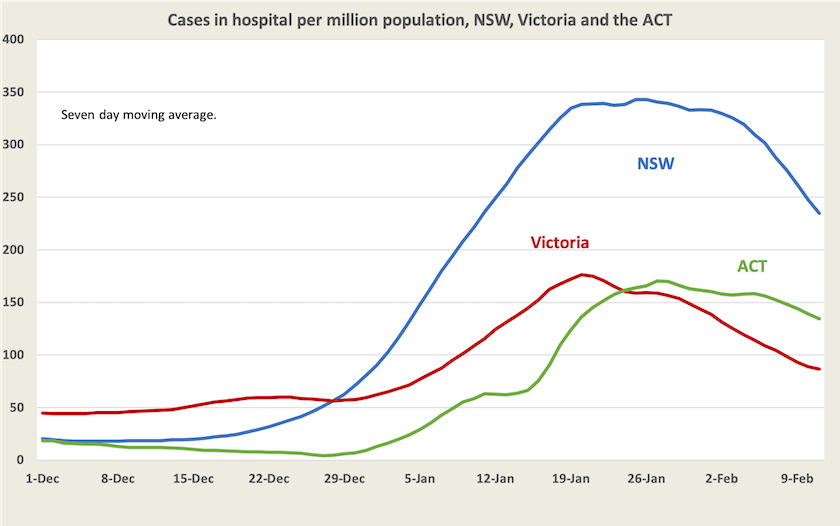

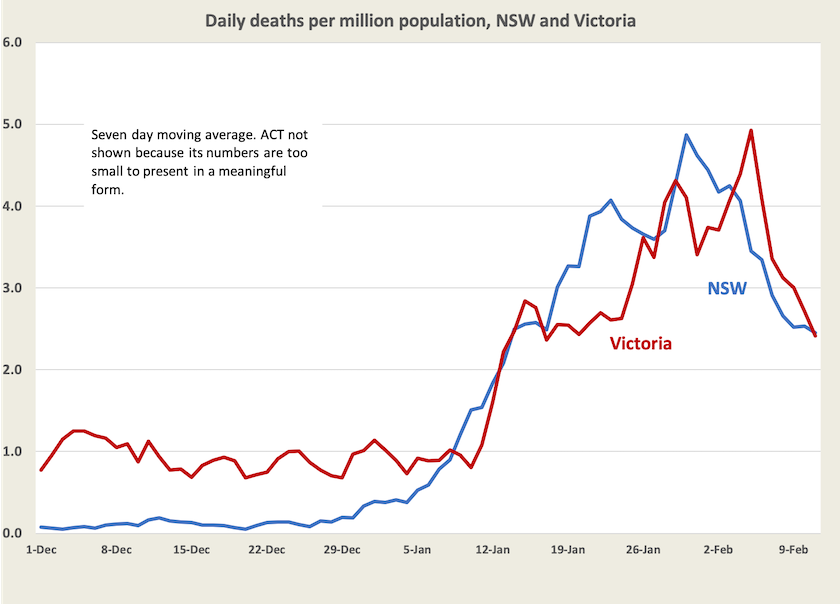

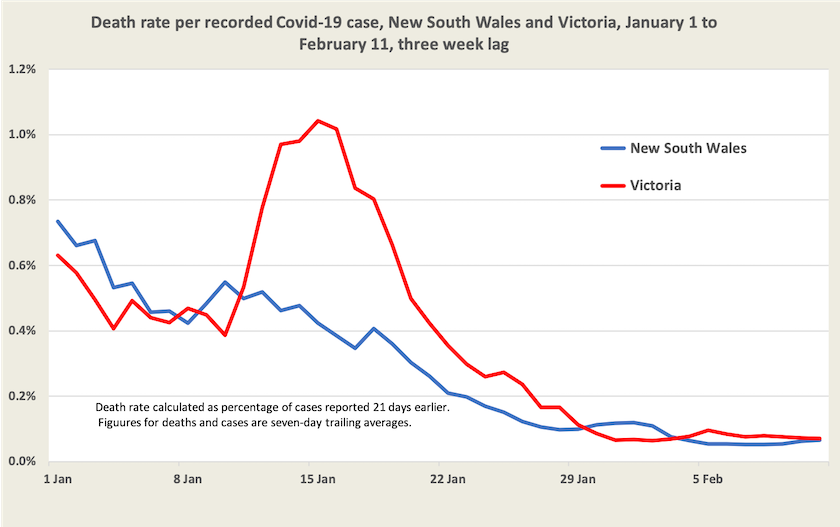

Again, the story is told in four graphs – cases, hospitalizations (the number of people in hospital, not the number of people being admitted into hospital), deaths, and, most important, the rate of deaths for those who have contracted Covid-19. I use data mainly from New South Wales and Victoria, where the Omicron wave is most advanced, and where the numbers are large enough to iron out the bumps in the data.[2]

First, on cases, or at least recorded cases, there is evidence that the daily case rate is plateauing in states and territories where Omicron first broke out. This could be an artefact of measurement, because as more rapid antigen tests become available more cases are detected and recorded: notably in New South Wales and Victoria most recorded cases now come from RATs. It could reflect the return of children to school, acquiring and detecting more cases. It could reflect a greater rate of transmission in the sub-variant of Omicron.

We might notice that faint line on the bottom of the graph. That’s Western Australia, where case numbers are growing at a high exponential rate. Expect it to show up more clearly next week. In the Northern Territory there are particular problems in remote Aboriginal communities (which could occur in Western Australia in the next few weeks).

Hospitalizations in New South Wales and Victoria have peaked and are falling, about a week to ten days after cases peaked. Although hospitalization figures don’t tell us much about the number of people being admitted to hospital, except by inference, they provide a reliable indicator of the load on the health system. That burden is still high. A quick glance at the New South Wales weekly surveillance report for the eight weeks to 22 January (quite dated) indicates that about 1.2 percent of people recorded as catching Covid-19 are hospitalized.

Deaths in New South Wales and Victoria have peaked and are falling, about two weeks after hospitalizations peaked. Again, from the same New South Wales weekly surveillance data, it appears that about 0.1 percent of people who contracted Covid-19 over the eight weeks to 22 January died. Note that although the Delta variant is now gone in NSW, this period would include many who contracted Delta, and it would have included few people with a fully-effective third dose of vaccination. Also this data refers only to recorded cases.

Then, derived from case and death data, with a three-week lag, is the death per case in these states, indicating that the death rate per recorded case is about 0.07 percent, or about 1 in 1300, broadly in line with what is revealed in the New South Wales epidemiological data.

[2] All data in these graphs comes from the website of collated official data maintained by Juliette O’Brien and her colleagues.↩

Who is “fully vaccinated”?

The latest Essential Report asks respondents how they think the term “fully vaccinated” should be used in the future. Only 31 percent accept the two-dose definition, while 57 percent say it should apply only to those who have had three doses. In the same vein, ATAGI has recommended the term “fully vaccinated” give way to the term “up to date”, which would apply to those whose vaccinations are in line with recommended doses for their age. If more than six months have passed since someone’s second shot and they are eligible for a booster, they will be considered as “overdue”. It’s official: you now need three doses says Norman Swan.

This is relevant in a situation where the Commonwealth has decided to open the borders to people who are “fully vaccinated” on February 21, by which Morrison means vaccinated with only two doses.

Presumably the electoral situation in north Queensland, where a number of seats are in contention, has influenced this decision. Whether it will work is another matter: the idea of inadequately-vaccinated foreign travellers coming to our tourist hotspots may cause domestic tourists to re-think their plans. But perhaps ordinary Australians whose travel is in low-cost ways such as motorhomes and Airbnb apartments, don’t really count, when the bug bucks are with the airlines and five-star resort operators.

The same Essential survey asks people about whether they have had a third vaccination shot and if not, if they intend to get one. Only 5 percent respond that they “don’t intend to get a booster”, while another 8 percent respond that they haven’t gotten around to it. Otherwise people had either booked an appointment or were waiting the required time after their second dose.

As at 11 February 37 percent of all Australians, or 46 percent of adults, have received three doses, and there is a strong rate of uptake.

The cost of haste in opening up

No one seriously suggests that we could have kept Omicron out of Australia. It is so infectious that we could not have kept on with a policy of local elimination. But with a few basic public health measures we could have slowed its spread, allowing time for more people to get fully vaccinated, more drugs to treat Covid-19 being available, less load on our health system (with consequences for people needing attention to other conditions), and more time for aged-care establishments to get organized. Surely many of the 2300 deaths that have occurred over the last two months could have been avoided.

With urging from so-called “business interests”, particularly the airlines, and from Morrison, New South Wales’ newly appointed Dominic Perrottet was in a rush to open up, however. ABC business editor Ian Verrender explains the cost of this haste: Health versus wealth and the unexpected costs of Australia opening up early as Omicron wreaks havoc. This idea of some trade-off between “health” and “economic” policies is an enfeebled way of thinking about public policy.