Economics

Australia’s economic outlook: two versions

Morrison’s election pitch: I can manage the economy because I’m Scott Morrison

Morrison’s speech to the Press Club was true to his established form – all spin.

In his Press Club address Albanese had four statements about Labor’s vision for Australia; so Morrison had to set his theme around five “priority areas”, but unlike Albanese’s statements all five were general statements of the obvious: what government wouldn’t claim to attend to the economy, to continue to provide essential services, or to protect Australia’s interests?

Drivel.

The only hint of an economic policy comes in two statements:

You can’t run the Australian economy on taxpayers [sic] money forever.

and

Our task now is to continue our economic recovery by sticking to our Economic Recovery Plan [whatever that is] and, importantly, exercising the fiscal discipline necessary to ensure that we do not overburden future generations and continue to spend taxpayers’ money wisely.

That is a pitch for austerity, provided we overlook the tax cuts for people with high incomes.

We can expect the budget delivered next month (assuming the government doesn’t implode before then) to have pre-election handouts – $X million over 4 or 10 years – which will provide headlines for The Australianand gullible journalists in other media. Most journalists were expecting Morrison to include in his speech the $400 to $800 payment to workers in aged care, the second tranche of which is to be delivered just before the election. But he didn’t include it, probably because unions, aged care providers and anyone who has mastered primary school arithmetic knows that it is only a 2 percent pay rise for one year, rather than a permanent boost in pay for a badly under-rewarded workforce.

Much of what is important in economic policy was absent from his speech. Productivity got only a passing reference: yes, we all want to see productivity lifted, but he made no mention of the fact that labour productivity has been on a downward slide since the Coalition was elected in 2013. As for other economic concerns – the crisis in housing affordability, inflation which will be followed by higher interest rates, and the growth of precarious work – these problems may as well not exist. Nor did immigration get a mention: in a country like Australia the easiest way to get unemployment down is to lift the drawbridge. Infrastructure got a mention, but only in the context of re-announcing work already committed: in fact successive Coalition governments have been cutting infrastructure spending.

While his speech was generally considered to be dull and low key, his arrogance and political confidence were on full display:

For the third year in a row, I have been invited as a guest to the G7 Summit, which will be held in June in the United Kingdom.

No Scott. You have not been invited: the prime minister of Australia has been invited. You are not the state. Australia is a democracy where people have the right to throw out an incompetent or corrupt government; it is not Xi’s China or Putin’s Russia. How dare you insult the people by assuming you have been invited personally and will still be prime minister in June.

The Reserve Bank: she’ll be right mate – well, maybe

On the following day Reserve Bank Governor, Philip Lowe addressed the Press Club about economic prospects for the year ahead.

His too was an optimistic presentation, but it was more qualified than Morrison’s, and was backed with reasons and arguments.

The RBA predicts that there will be a fall in the unemployment rate, to 3.75 percent by 2023, and because labour markets don’t respond quickly, there will be only a slow rise in wages. These predictions are heavily qualified, however, because the world economy is in uncharted territory.

Standing out in the RBA charts are high rates of job vacancies and advertisements, making one wonder if businesses posting those advertisements really appreciate that, for now at least, while immigration is low, there has been a shift in market power, and that they may have to start thinking about improving pay and conditions, rather than waiting for the award system to catch up.

The biggest gamble in the RBA’s forecast is about inflation, which they hope to contain within their 2 to 3 percent comfort zone. While they are ending the bond purchase program, they suggest that they will not act on interest rates until and unless inflation breaks out of that zone. That will be some time in the never-never, but “over time and as conditions allow, we will need to navigate a return to more normal settings of monetary policy”. That is to raise interest rates (but when?). Of all the arguments in the RBA paper, their reasoning about low inflation is the least convincing.

Just to make sure we don’t put too much faith in this document, or any other bullish economic forecasts, Lowe’s presentation started with a table comparing the forecasts the RBA made this time last year with the actual outcomes. Its worst forecasts were on inflation. So why should we believe they will do any better this time, when our exchange rate is low, when there is high inflation in other countries, and when there will be wage rises without any rise in productivity?

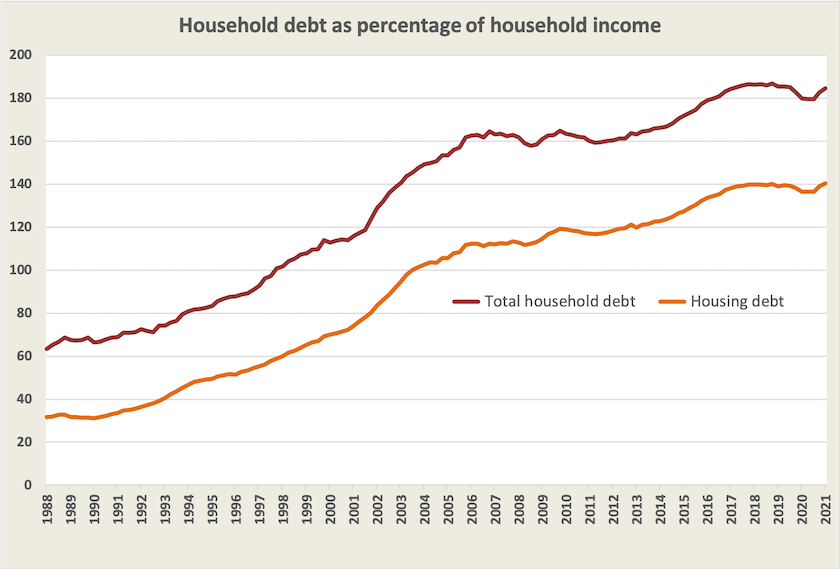

On the ABC 730 Report Alan Kohler describes warnings Lowe gave to highly indebted households (probably in response to questions, for his prepared speech avoided mention of household debt or house prices). Because interest rates have been so low, any increase, although low in terms of percentage points, will hit mortgagees hard. (4 minutes)

In view of the high level of household debt, as shown in the figure below (plotted from RBA statistics), it’s a timely warning. Note that most of that debt is housing debt, presumably mortgage debt, and because many younger people cannot afford to buy a house, and many older people have largely or completely paid off mortgages, that debt would be heavily concentrated among a small proportion of the population – young people who have recently bought into an over-inflated housing market, and over-leveraged speculators. On the ABC’s Breakfast program Martin North of Digital Finance Economics provides more detail about those who will be facing, or are already facing, stress in repaying housing loans. (5 minutes)

Peter Martin: let’s return to the good old days when 2 percent was considered as high unemployment

Writing in The Conversation Peter Martin asserts that Unemployment below 3 percent is possible for the first time in 50 years – if Australia budgets for it. He goes on to suggest that it could be pushed even lower with the right policy settings, particularly measures to help the unemployed connect with employers. He asks, however, if governments’ short-term concern with “budget repair” (whatever that means – the budget isn’t broken) will discourage governments from making such a commitment.

(In 1961 the unemployment rate rose to 2.6 percent, the first time it exceeded 2.0 percent in the postwar era. In the election that year the Liberal Party suffered a huge swing against it. The Menzies government was returned with a one-seat majority, having been saved from defeat by the Communist Party preferencing the Liberals over Labor in its how-to-vote cards.)

Oh what a lovely pandemic!

While the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission properly goes after retailers for price gouging in the supply of rapid antigen tests, the big bucks are in vaccines developed, manufactured and distributed by pharmaceutical firms.

The pharmaceutical industry is characterized by huge costs incurred in research and development and in running clinical trials. Much of this work goes nowhere, but when they get a breakthrough, profits are enormous, because the cost to manufacture drugs is low. Each extra dose is almost pure profit. That’s why they’re so keen to promote their products to regulatory authorities, and to protect their intellectual property.

Normally they don’t like vaccines, because once someone is immunized there is no repeat business, and herd immunity is a commercial dead end. But Covid-19, because of its virulence and transmissibility, and because repeat doses are required, has provided the industry with the opportunity of a lifetime.

If you have half an hour to spend, you can listen to the ABC’s Keri Phillips on the Rear Vision program talk to several people about the history of the pharmaceutical industry, an industry that starts with street-corner compounding chemists, and develops into today’s Pfizers and Mercks: Big pharma and the Covid windfall.

The industry has benefited tremendously from publicly-funded research in universities. The US National Institutes of Health provide $US30 billion a year for basic research, and in recent years that research has been moving closer to full development, reducing the risk faced by pharmaceutical firms. In the case of Covid-19 their risk has been further reduced by governments around the world (with one exception we all know about) signing on to purchase guarantees early in the process. Although they have socialized their losses and privatized their profits, the pharmaceutical firms still insist on patent protection and are reluctant to participate in the COVAX program by sharing intellectual property. (A cynic might say that an unvaccinated pool of people in poor countries, in providing a nursery for new variants, provides a superb ongoing opportunity for the industry.)