Politics

Labor’s campaign start: Albanese’s Press Club address

“Australia needs good government now more than ever”.

That was a strong theme in Albanese’s Press Club address last Tuesday: Australia’s best days are ahead.

It was hardly a speech of revolutionary fervour. Rather it was a no-nonsense platform by an alternative prime minister, promising to provide more responsible public administration than the rabble now in office.

That is not to say it was devoid of policy – “small target” as some journalists say about Albanese’s strategy. He summarized Labor’s policy direction in four statements about the Australia Labor envisages. One could skip over them, suggesting that any aspiring prime minister would say something similar, but in fact they represent a significant departure from the policies and priorities of the Morrison government – to the extent that the Morrison government has any consistent set of political principles.

To go through each of the four statements in turn:

An Australia with rising living standards, lifted by more secure work, better wages, better conditions for small business, stronger Medicare, and more affordable child care.

That contrasts with the Coalition’s policy of keeping wages low and insecure in order to ensure that the workforce meets the (supposed) needs of employers. The re-assertion of Medicare is noteworthy, and further in his speech he makes a strong commitment to public health.

An Australia with more secure jobs in both existing and new industries – industries that will be reaping the benefits of cheap, renewable energy.

To Labor climate change presents an opportunity for structural renewal. To the Coalition adjusting to climate change is a burden that will cost jobs and raise prices, and which must be responded to with the bare minimum to meet international demands.

An Australia that is secure in our place in the world, standing up for Australian democratic values and for human rights on the global stage.

We are not a pathetic remnant of the British Empire that must subordinate our foreign policy to others.

An Australia reconciled with ourselves and with our history, and with a constitutionally recognised First Nations’ Voice to Parliament.

Remember what the Coalition has done with the Uluru Statement.

Australia needs a government “of competence and integrity” he said, “a government that doesn’t get out of the way but helps to create the way, a real government is the steering wheel of a nation, not just a bumper sticker”. That’s a reference to Morrison’s muddled and inconsistent economic thinking – a thinking that has seen billions of stimulus payments given to firms that didn’t need it, alongside a refusal to fund rapid antigen tests. Albanese has an idea of the roles of government, markets and civil society in a way that is completely lacking in the Coalition.

Unsurprisingly he stated the need for a national anti-corruption commission “to restore faith in government and trust in our public officials”.

Tellingly, Albanese recognized the forces threatening to undermine democracy in Australia:

Our system is no more immune to the threat of extremism and polarisation and the decaying, corrosive influence of corruption and cynicism than other democracies around the world – many of whom are grappling with these very challenges.

That much is in his prepared speech – a speech that would have been carefully crafted with contributions from many political minders. It is in handling questions that a politician shows his or her grasp of policy issues.

Many questions were about how Labor would handle current issues, particularly dealing with Covid-19. No surprises in his responses.

Some journalists demanded that he make fiscal commitments, but apart from the modest promise to spend $440 million on schools to deal with Covid-19’s consequences, he wisely kept the discussion on a more principled level: in view of the uncertainty in the world right now, it would be futile for anyone to lay down a firm fiscal plan. But that didn’t stop a journalist from one of the Murdoch papers asking how Labor would deal with government debt and “repair” the budget, as if all that counts in economic management is the cash balance, and as if the budget is “broken”, whatever that means.

Albanese’s reply to that question gave him an opportunity to differentiate between the Coalition’s profligacy in its fiscal stimulus and what responsible economic management would look like. Apart from some undeserved profits in firms that rorted “Jobkeeper” and other stimulus programs, there is no legacy from the $1 trillion debt: there is nothing on the other side of the national balance sheet. In fact, the Coalition has actually cut infrastructure spending. “This Government has no credibility when it comes to economic management”.

Another question from a Murdoch journalist asked Albanese to make a commitment on taxing family trusts – the mechanism used by small business to avoid paying their share of taxes. The journalist asked if Albanese will re-assert Labor’s commitment to taxing trusts.

Albanese wisely avoided the “rule it in” or “rule it out” trap in that question: he had no intention to give the Murdoch media and the Coalition the opportunity to run a deceitful campaign misrepresenting Labor’s fiscal policy.

And just to put aside any suggestion that Labor has a “small target” strategy, Albanese reminded us of what Labor has put on the table in the last few weeks:

… an expanded NBN, a climate policy which is fully costed, 465 000 free TAFE places, 20 000 university places in addition, a policy of 500 new community workers to deal with domestic violence, a shipping policy that includes a strategic national fleet, high-speed rail being a priority from Newcastle to Sydney as the first leg, a policy of disaster preparedness using the ERF, a Great Barrier Reef Fund policy, and additional Indigenous rangers. That's since December.

Aged Care Minister Colbeck was too busy to show up to the Senate: he was watching the cricket

On Wednesday’s ABC Breakfast program shadow Finance Minister Katy Gallagher explained her frustration at Minister Colbeck’s refusal to attend a Senate hearing into the government’s response to Covid-19, even though there is a crisis in aged care, relating to booster shots for residents and staff and the availability of rapid antigen tests. The minister claimed that he couldn’t attend because he was busy attending to the aged care crisis. But in fact he was in Hobart enjoying three days of corporate-sponsored hospitality at the cricket. Labor's Katy Gallagher accuses Aged Care Minister of 'arrogant complacency' for attending cricket match. (9 minutes)

In addition to refusing to turn up himself, he instructed officials in the Department of Health (which has responsibility for aged care programs) not to attend the hearings.

Gallagher made the point that should be obvious, but which isn’t appreciated by the minister or the departmental staff, that the minister and public servants are accountable to parliament, the nation’s law-making body that appropriates the resources to allow them to perform their duties.

Although not specified in our constitution (which makes no mention of the public service) it has become a convention that public servants place the authority of a minister over the authority of parliament, and when they do appear before parliamentary committees they see it as their duty to protect their minister from embarrassment. We have allowed ourselves to slip slowly from a system of parliamentary democracy to a system of elected dictatorship.

Corruption has worsened on the Coalition’s watch

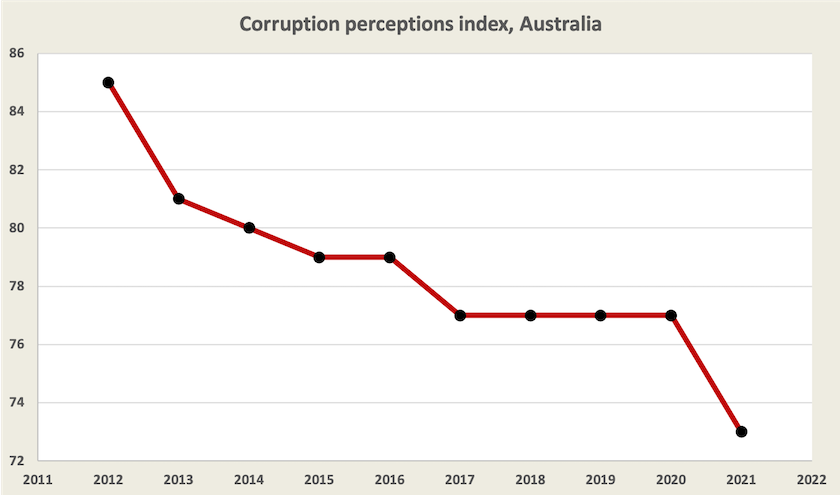

The graph below shows Transparency International’s corruption perceptions index for Australia over the last eight years – a period that starts with the election of the Coalition in 2013.

The index is compiled from manifestations of public sector corruption, including bribery, diversion of public funds, nepotistic appointments in the public service, state capture by narrow vested interests, and the absence of measures to protect against corruption.

Transparency International compiles the index for 180 countries. The top three positions are held by Denmark, Finland and New Zealand, followed by Norway, Singapore, Sweden and Switzerland. Australia is down at position 18, having slipped four places just in the last year. Even the UK now ranks ahead of Australia.

Its specific comments on Australia include the observation of why our score has slipped from 85 to 73:

Australia (73) has been one of the world’s most significant decliners (from 85) over the last decade – and it has lost four more points this year. The country continues to have no national integrity commission to prevent and detect corruption. Also, lobbying regulations fall short of international standards and enforcement is weak against companies paying bribes to secure contracts abroad.

The Liberal Party swings even further to the right

Writing in The Guardian Anne Davies reports on pre-selection battles in the New South Wales Liberal Party for an upcoming round of state by-elections to be held on February 12: The right stuff: why shellshocked NSW Liberal moderates are fearing factional fights. Her main story is about Gladys Berejiklian’s former seat of Willoughby, a safe Liberal seat where a candidate “with a record of pushing development of gas and opposing higher carbon emissions reduction targets” has won pre-selection.

This is not an isolated New South Wales issue. Davies reports that in other states the Liberal Party has experienced an influx of “climate-denying Christian conservatives”, some Pentecostalist, some Catholic. (It’s strange that although these people call themselves “Christian”, they are unable to point to any part of Christian scripture or moral doctrine that gives the faithful the go-ahead to vandalize God’s creation.)

When will the election come?

Unless Morrison goes for having only a half-senate election in May (an option last exercised in 1970) and delaying a House of Representatives election until September, May 21 is shaping up as the last date there can be an election for both houses. Most pundits suggest he will call an election for that date. The general thinking is that by that stage we will be living with Covid-19, with infections and hospital admissions having fallen to low levels. We will have forgotten Morrison’s neglect and stuff-ups of aged care, vaccines, and test kits, his government’s gifts of stimulus funds to already highly profitable companies, his diplomatic gaffes, his government’s use of discretionary grants as if they were Liberal Party electoral funds, his awkward dealing with women in public life and his loose relationship with the truth – quite a lot to forget really.

But there are risks in any delay. Even if the Reserve Bank holds back, market interest rates are bound to rise, and the market for apartments is showing a few early wobbles. Naïve and over-leveraged property speculators can get very angry when their dreams of easy wealth are shattered. And for the population at large cost-of-living pressures are starting to bite: as we go back to the shops or download our bills, we notice that prices have risen.

Paul Karp, writing in The Guardian, reminds us of another timing problem for Morrison. Unless he calls an election very soon, he will have to recall parliament, where he will be confronted by angry senators demanding an inquiry into Australia’s Covid-19 response. This is a hard one for Morrison, because the calls are coming from senators on the hard right, dissatisfied with Morrison’s failure to override state governments’ lockdowns and mandates, and from more reasonable senators – Labor, Green, independent – who want to focus on Morrison’s mishandling of vaccination and other Covid-19 matters. As Karp points out, it’s not only in the Senate but also in the House of Representatives that Morrison is facing a challenge on his government’s performance in dealing with the pandemic.

Ukraine: it’s about much more than Russian aggression

Various commentators provide a little more background on the tension along Ukraine’s borders.

Writing in The Conversation, Tatsiana Kulakevich outlines 5 things to know about why Russia might invade Ukraine – and why the US is involved. While the vast majority of Ukrainians have a negative attitude to Russia and to Putin, there is something of an east-west divide within the country: the eastern regions are more sympathetic to Russia. Also, in spite of the official line about western European unity, there are many in western Europe who believe that Europe should be more accommodating of Russia. For example German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder when he was in office (from 1998 to 2005) advocated for strategic cooperation with Russia. Just last week the head of the German navy stepped down after publicly saying Crimea was lost to Ukraine and that Vladimir Putin probably deserved respect.

Deutsche Welle has a 5-minute clip describing Germany’s dependence on Russian gas: How the EU's need for gas complicates the Russia-Ukraine crisis. There are other sources of gas in the world but they would be more expensive and as in other countries fuel prices are a sensitive political issue in Europe.

On the ABC’s Late Night Live, Phillip Adams interviews Joshua Yaffa, Moscow correspondent for the New Yorker, on the crisis as seen from Moscow. The conflict is still about unresolved business from the Cold War. Even though there is no current proposal to bring Ukraine into NATO, it is moving further towards western Europe in its alliances. This is not how Russia believed the post-Cold War order would work out. (15 minutes)

Most commentators see the conflict in terms of a security border between Russia and NATO. Another aspect of the conflict, possibly more important, is an ideological border, as Constanze Stelzenmuller of the Brookings Institute explains on the ABC’s 730 program: What are the political ramifications if Putin orders the invasion of Ukraine?. The example of Ukraine, a Slavic country, adopting a western-European model of liberal democracy would be threatening to Putin, and could undermine the legitimacy of his dictatorship. (5 minutes)