That inscrutable virus

Worldwide: a muddier picture is emerging

In October last year the WHO set a target for countries to have 70 percent of their population vaccinated by the middle of this year.

With only five months to go we are falling short. Worldwide just over 50 percent of people have received two doses of vaccines, and 11 percent have had a third shot, but these gross figures do not reveal stark differences between different countries, and even differences within countries. The most concise presentation of vaccination around the world is a map on the New York Times website Tracking coronavirus vaccinations around the world. Almost all countries in Africa and a few countries elsewhere – including Myanmar and Papua New Guinea in our region – have very low rates of vaccination, while many well-off countries are well on their way to covering their populations with booster doses.[1] The same site has a map of vaccination rates within the USA: it looks remarkably similar to a map of Democrat/Republican support in the 2020 election.

CNBC has a map of countries that have met the 70 percent WHO target, or are on track to do so. Western Europe, “developed” Asian countries (including China), and a few other countries including Australia and Canada, have already met that target. But among countries “not on track” are most of Africa, the USA, and most of eastern Europe.

The implications for the emergence of new variants of Covid-19 are clear, and these targets were set before the Omicron variant appeared, against which two-dose vaccination (which is still called “full vaccination”) is of limited effectiveness in preventing infection.

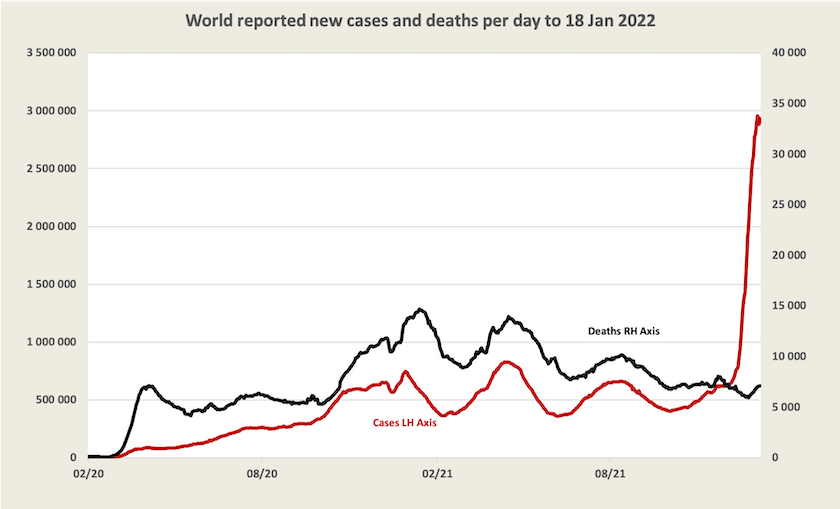

As for Omicron, the chart below, based on WHO data, tells part of the story, at least for those countries that record Covid-19 cases and deaths. We can see that deaths were tracking cases of Covid-19, with a small lag. A year ago Covid-19 seemed to be on the way out, but then came Delta, which saw a rise in infection and deaths followed by another decline in cases and deaths.

Now there is a massive jump in Omicron cases, but with only a small uptick in deaths. The infection-death link is weakened, but as yet we cannot be sure whether this is because more people are vaccinated, because Omicron is less deadly, or because it is breaking out in populations where treatments are better.[2] And we don’t know much about what’s happening in countries that aren’t recording infections.

Because Covid-19 keeps throwing up new variants, the pharmaceutical industry is in a difficult position. There will probably be an Omicron-specific vaccine available in a few weeks, but will pharmaceutical firms go to the trouble of obtaining regulatory approval and gearing up production, and will governments commit to purchasing the new vaccines and rolling them out, when Omicron may be displaced by yet another variant? As Charles Schmidt writes in the Scientific American “the virus is evolving new mutations faster than vaccine makers can keep up”. One answer may be faster regulatory approval, he suggests, or perhaps we should patiently wait for a general variant-proof Covid-19 vaccine, which could still be two years away: What’s holding up new Omicron vaccines?.

Perhaps it’s too heretical for policymakers to think of globally-funded vaccine development as a shared public good, overcoming the commercial disincentives for private firms to develop vaccines.

1. In Africa only 10.1 percent of the population is “fully” (two-dose) vaccinated. In Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Malta, Norway, Korea, Singapore and the UK, more than 40 percent of the population have had a third dose. ↩

2. The break between deaths and infections is probably even more dramatic than is implied in this graph, because while infections have become hard to trace, deaths are more easily recorded and attributed to Covid-19. ↩

Australia

Omicron – we’re well protected, but only if we have had a third dose

Because Omicron has caught us unprepared, and has rapidly overloaded PCR testing capacity, we don’t have a clear picture of what’s going on. Adrian Esterman, Professor of Biostatistics at the University of South Australia, writing in The Conversation, says there are four numbers we should keep an eye on – the number of new cases, the virus’s effective reproductive number (“Reff”), the percentage of positive tests and the number hospitalised, but unfortunately we don’t know any of them with any certainty.

We have seen reference to “hospitalisations” – indeed the prime minister and others say we should focus on hospitalisations rather than cases – but the figures released by the health authorities are not particularly informative for the general public, because they are about the number of people in hospital with Covid-19. That’s a useful indicator of the load on our health systems, but it says nothing about the number being hospitalized every day. We hear and see journalists referring, in their daily news reports, to the number of cases, the number of “hospitalizations”, and the number of deaths, but in doing so they are only causing confusion, by interspersing a stock variable (hospitalizations) between two flow variables (cases and deaths). If we confuse the number of people being admitted to hospital with the number of people in hospital we can get an alarmingly high impression of the risk of suffering a severe case of Covid-19.[3]

It is worth paying attention to the number of cases being detected and recorded, but because of the number of asymptomatic cases, the unavailability of RAT tests, and the reluctance of some people to get tested, the recorded number of tests is significantly understated – possibly by a factor of 5 or even higher as Norman Swan stresses. That means the rate of deaths per case and any guesses about the rates of hospital admissions are correspondingly overstated. Another complicating factor is that there are lags between diagnosis and admission to hospital and between admission and deaths. Today’s deaths relate to cases detected some time ago (two or three weeks) and today’s hospital admissions relate to cases detected a few days earlier (perhaps about a week).

Some professional interpretation of these figures is provided by the Weekly Surveillance Report produced by the New South Wales Department of Health. The latest report, for the week to January 1, has a large amount of information. Because it takes time for the Department to collect and analyse the data, much of it relates to people still infected with the Delta strain, and because New South Wales has a high level of vaccination (78 percent) most infections, hospitalizations and deaths are among the fully vaccinated: the figures need to be read and interpreted with care.

It finds that among cases detected between November 26 and January 1, only 1 percent were hospitalised. Among cases of those aged 60-69, 3 percent were hospitalized, for those aged 70-79, 10 percent were hospitalized, and for those aged 80-89, 22 percent were hospitalized. Note that these rates refer to all cases, vaccinated or unvaccinated, although people over 70 were almost certainly “fully” (two dose) vaccinated.[4]

The same report has some further data related to vaccination status. Fewer than 1 percent of people with “full vaccination” (two doses) suffered a “severe outcome” (ICU or death), and the rates of severe outcomes were still very low for people aged over 70 (1 percent for those aged 70-79 and 3 percent for those aged 80-89). It should be borne in mind that these are figures for recorded cases only, and they would include very few, if any, people who had received boosters. They would therefore almost certainly significantly overstate the risks of hospitalization and deaths for people in all age groups.

Norman Swan, on Friday’s Coronacast – Is the death rate too high? – has some up-to-date interpretation, based on UK data, on the capacity of vaccination to protect against infection and severe disease. It is understandable that there are people with two-dose vaccination suffering severe illness or even death, because two-dose vaccination, while giving some protection against Delta, provides little protection (perhaps none) against Omicron. But those who have received a third dose have excellent protection, not only against severe illness but even against infection. Many people have been dying for want of a booster, he says. “British data shows very clearly that boosters are fantastic”, and so far it looks as if they sustain protection against hospitalization.

The Sydney Morning Herald has an article Omicron cases less likely to enter hospital, but numbers cause strain, presenting some key findings from the New South Wales report, and providing short comments from experts. (You can probably get one download before the firewall kicks in.) The message is that with a third dose, the risk of hospitalization is small, and the risk of death is very small.[5] (Swan’s latest report suggests that even this interpretation overstates the risks of hospitalization and death.)

Where to from here?

That isn’t to suggest that Omicron is “mild”, an interpretation that some policymakers use to forecast that we can get back to a pre-2020 lifestyle once this annoying little wave passes. It’s still a nasty disease, as Katherine Wu writes in The Atlantic: Calling Omicron “mild” is wishful thinking. And it isn’t going away, as Raina MacIntyre explains in The Saturday Paper: Why Covid-19 will never become endemic. (Paywalled but The Saturday Paper is good value.) She concludes:

There is a massive vaccine and drug development effort, so it is almost certain we will have better vaccine options, including ones that are variant-proof. But what the past month has shown us is we cannot live with unmitigated Covid-19. Vaccinations will not be enough. We need a ventilation and vaccine-plus strategy to avoid the disruptive epidemic cycle, to protect health and the economy, and to regain a semblance of the life we all want.

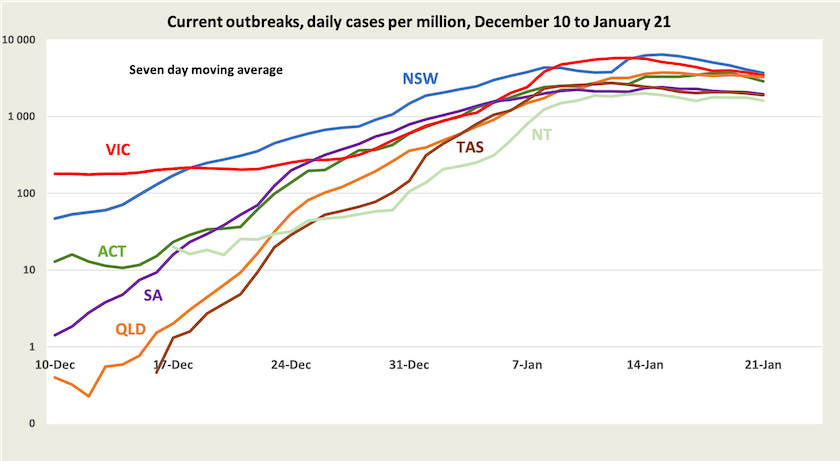

For now, it appears that in the states where the latest wave started to spread (New South Wales, Victoria and the ACT) cases may have have peaked, as shown in the chart below. We will have to wait a bit before deaths start to fall. Because the chart uses a logarithmic scale and the data is smoothed, the peak doesn’t appear to be sharp, but it probably occurred in these states about a week ago.

The qualification of this chart is that it’s based on recorded cases, and it is drawn with the assumption that although the actual number of cases is understated, the ratio between recorded and unrecorded cases is pretty well constant. Maybe there will be a rapid fall in cases as some predict, but that would occur only if the virus is running out of people to infect.[6] Maybe it will come and go in waves: as cases fall we will become complacent and ease off on public health measures, giving the virus a chance to have another go. As Tory Shepherd writes in The Guardian, we don’t know enough about how this variant is behaving in Australia. Maybe that’s because our policymakers are unused to using evidence to support policy and are unused to sharing information with the public.

In view of what we know about Omicron and the effectiveness of boosters, Western Australia’s caution in delaying opening its border is understandable. As Norman Swan points out on Coronacast, it is also quite understandable that other states are shortening the gap between the second dose and a booster. Regrettably, had the Commonwealth been more assertive in promoting boosters we could have avoided many deaths, ensured that hospitals did not become overloaded, and avoided such a slowdown in activity generated by people’s fear of infection, hospitalisation and death.

Bad public policy – callousness or stupidity?

When the Omicron strain emerged in late November it would have been hard, if not impossible, to have kept it out of the country. But a wise policy, which was probably urged by public servants advising governments, would have been to slow its spread through public health measures – mask mandates, restrictions on crowd sizes, density limits in indoor businesses, closure of nightclubs and so on. This would have given time for shots for children to be rolled out, prioritisation of residents and staff in aged care and indigenous communities for booster shots, ordering medicines for treatment of Covid-19, and ordering rapid antigen tests.

Above all it would have allowed hospitals to cope without placing undue demands on health staff and requiring the deferral of “elective” procedures (a classification that includes many life-threatening conditions).

Understandably, with Christmas and the holiday season approaching, and with people having achieved a high rate of vaccination, people were looking forward to putting border controls behind them. Even when news about Omicron broke, people latched on to the rumours that it was nothing more than a minor irritant. In the magical atmosphere of Christmas people were not in a mood for bad news.

Public health officials advising governments would have been cautious, and would have urged governments to amend or defer their plans for relaxing restrictions. But this wasn’t the path taken by the New South Wales government. Backed by the prime minister, their approach was to let it rip (“push through” was the slogan crafted by Morrison’s spin doctors), and other states in the national cabinet went along with their plans to open up. The policy became politicized: we could either enjoy getting the government off our backs, as Morrison put it, or suffer the oppression of lockdowns as would happen if those evil Stalinists in Labor had their way.

Supposedly the relaxation of restrictions was to ease pressure on the economy, even though the consequent damage has been at least as bad as any lockdown and far worse than would have been incurred by application of basic public health measures. A visit to a supermarket with empty shelves, or a walk past closed shops, illustrates the economic damage inflicted by Omicron. One early indicator, the ANZ-Roy Morgan index of consumer confidence, which normally rises in January, has taken a tumble in the latest survey.

The figures on hospitalization collated by Juliette O’Brien and her colleagues reveal the extreme stress on our health system. Those who find numbers too abstract could listen to a 5-minute clip of interviews with nurses and health policy experts on the ABC PM program Covid overwhelms health workers. No one on the public payroll wants to say, explicitly, that standards of care are being compromised, but anyone who has the experience of working fifteen or twenty-hour shifts, day after day, knows what happens to human judgement.

Over the first three weeks of this year, there have been 731 Covid-19 deaths in Australia, 359 of them in New South Wales. To put this into perspective, from the first appearance of Covid-19 in early 2020 until August 2021 there were only 1000 Covid-19 deaths in Australia. No one would claim that all these recent deaths were avoidable, but many could have been avoided if there had been more time for vaccination to be administered and to take effect, and if the spread could have been slowed down to allow better treatments to become available. (Only on Thursday this week has the TGA approved two new anti-virals for Covid-19.) Also these figures do not pick up deaths and unnecessary suffering resulting from an overloaded hospital system.

On the ABC’s 730 Report Clare Skinner, President of the Australasian College for Emergency Medicine, describes the pressures on people working in our health system. While the number of cases may be peaking, the load on hospitals is becoming heavier because of lags between infection and development of symptoms and because more vulnerable cases are presenting at hospitals. She concludes with a call for basic reform of our health care system:

The hospital system has been fragmented and difficult to navigate for years. This is not just a Covid phenomenon: it has been building for years with increasing out-of-pocket costs. What we need to do is make sure that we remember how it feels right now. We’re seeing the fault lines exposed through Covid. Care is difficult to access; but it is particularly difficult to access for the most vulnerable in our community, those with complex and chronic disease, those with low levels of education or income and those who are marginalized for other reasons. … As we emerge from this wave we need to make sure that health reform is on the political agenda because we need to make sure we design a health system that is safe, fair and accessible for all Australians.

It is hard to know what has driven bad policy in dealing with the latest wave of infection. Perhaps there was a callous calculation, balancing a few deaths against the supposed benefits of economic activity, particularly in the lead-up to an election. The health system would be overloaded, but that’s mainly in the public sector, and the Liberal Party is grounded in the belief that all that is good comes from the private sector while the public sector is just an indulgent and unproductive overhead. Or, as is more likely, and more morally defensible, this policy is explained by sheer stupidity – a failure to understand the basics of economics, a failure to grasp the simple mathematics of exponential growth, and a faith that one should be guided by gut feeling rather than the advice of experts. The Liberal Party has always compensated for its deficit in competence with a surfeit in confidence.

3. If one divides hospitalizations by the number of cases, the resulting rate looks really scary. For example, on Thursday New South Wales reported 30 285 cases, 2 781 hospitalizations, and 25 deaths. A crude calculation (confused by the hospitalisation figure) would have one believe that someone who catches Covid-19 has a 9 percent chance of being hospitalized (2781/30285) and a 0.08 percent chance of death (25/30285). This high hospitalization rate is a scary figure, but it’s very wrong because it confuses hospital admissions and the number in hospital, and because it is based only on recorded infections. ↩

4. Nationally, >99 percent of people aged 70 or over have had two doses of vaccination. ↩

5. Based on a three-week lag between diagnosis and death, and using a seven-day average to smooth out bumps, the current death rate in New South Wales is 0.26 percent. But even that low figure is based on very low and under-estimated infection rates, three weeks ago. Applying Swan’s 5 X correction, that indicates a death rate of around 0.05 per cent, or around 1 in 2000. ↩

6. So far, in this wave, NSW has recorded 0.81 million cases. That’s just on 10 percent of the population. But if we apply Swan’s 5X factor, around 50 percent of people in New South Wales have been infected. ↩