That bloody virus

First, some world figures

As at 12 January:

- 8 billion people, or 61 percent of the world’s population, have received at least one dose of vaccination;

- 1 billion people, or 52 percent of the world’s population, have received at least two doses of vaccination – still called “full vaccination” in spite of the limited effectiveness of two doses in protecting against infection;

- 7 billion people, or 10 percent of the world’s population, have received a third dose.

Vaccination levels remain particularly low (< 20 percent “fully vaccinated”) in most African countries and some other low-income countries. At the other end of the vaccination spectrum, in three countries – Chile, Denmark and the UK – more than 50 percent of people have received a third dose. Denmark and Israel are moving to a fourth dose for certain people. The low vaccination level in poor countries puts the whole world, rich and poor, at risk, because new variants are most likely to emerge among the unvaccinated.

The WHO Weekly Epidemiological Update of 11 January reports a recent significant rise in recorded cases worldwide, but no rise in deaths. Over the last four weeks, while there has been a 119 percent rise in recorded cases, there has been a 13 percent fall in recorded deaths, compared with the previous four weeks. These gross figures are consistent with the Omicron strain being far more infectious but less deadly than the Delta strain.

In countries classified by the WHO as “high income”, a category that includes the USA and Australia, there has been a small rise in deaths. In these countries the spread of Omicron has been so rapid that the rise in infections has overridden its lower fatality rate. The general pattern in these countries is that the Omicron variant has largely (or completely) displaced the Delta variant. This is particularly noticeable in the USA which continues to report about a quarter of the world’s Covid-19 deaths.

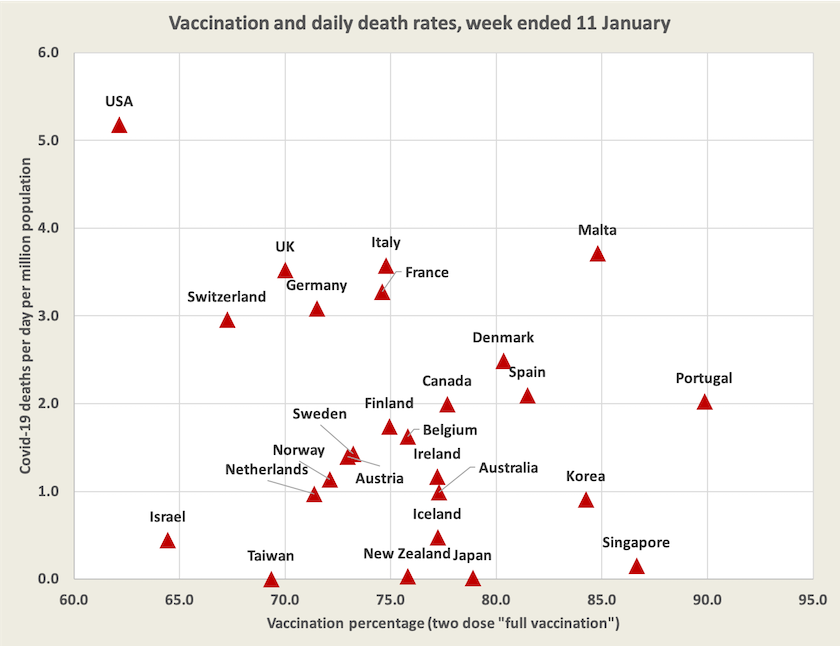

The diagram below shows vaccination levels and daily deaths per million, for a group of high-income countries. In the previous (9 November) presentation of this chart, in most of these countries daily death rates were mainly between 0.5 and 1.0 deaths per million population. Since then death rates have generally moved upwards. Australia’s daily death rate is recorded at 1.0 per million, but because Western Australia is still effectively quarantined, it would be more accurately represented as 1.1 per million population, and as will be seen in the next section, it is much higher in New South Wales and Victoria.

Infections in most of these countries are surging, and most infections are probably being missed by authorities because testing facilities are overwhelmed and many infections are asymptomatic. Vaccines are of limited effectiveness in protecting against infection against the Omicron variant, but they do seem to be protecting against severe illness and death. (As Norman Swan points out on Coronacast, now that there are too many infections to allow for genome sequencing, it is getting harder to trace the virus’s progress and the emergence of new variants.)

In these “developed” countries deaths are still occurring for three reasons: there is a long tail of people who contracted the Delta variant some weeks back; there are still large numbers of unvaccinated people; and the Omicron infection numbers are so high that even some well-vaccinated people are suffering severe illness and deaths.

Most countries’ governments have accepted that it is impossible to totally protect people against exposure to the Omicron variant, but they can slow down its spread in order to protect their hospital systems from being overloaded and to give time for vaccination to reach the harder cases – children and the hesitant – and for a third dose to be administered. Many countries are increasingly making life harder for those who deliberately choose not to be vaccinated, through restrictions on access to facilities and through financial penalties in some cases.

For those with 22 minutes to spare Britain’s John Campbell provides a reasonably comprehensive survey of what’s happening in in the USA and Europe, recorded on Tuesday. Campbell is among the group of experts who are reasonably optimistic about the path of Omicron. He expects infections will soon peak in most “developed” countries, with a lag in peak hospitalisations and deaths, but infections will move on to poorer and less vaccinated countries, particularly in Eastern Europe.

In a further session recorded on Wednesday Campbell reports on some promising data from California that reveals very low rates of hospitalisation and ICU admission for those with Omicron compared with hospitalisation and ICU admission for those infected with Delta. (He also provides some tantalising early data on natural immunisation against Omicron provided by infection from other coronaviruses, specifically the “common cold”.)

While it is reasonably well established by now that the Omicron variant is less deadly than previous variants, there is far less certainty about the effectiveness of vaccines in preventing infection from Omicron. Evidence available so far suggests that two doses of vaccine provide only minimal protection against contracting the Omicron variant. On the effectiveness of vaccines in reducing the severity of infection from Omicron there is a range of estimates among academic studies. Some suggest that the reduction in severity is only marginal, while others suggest it is quite significant. The third dose does seem to provide significantly more protection than the first two doses, however.

Australia

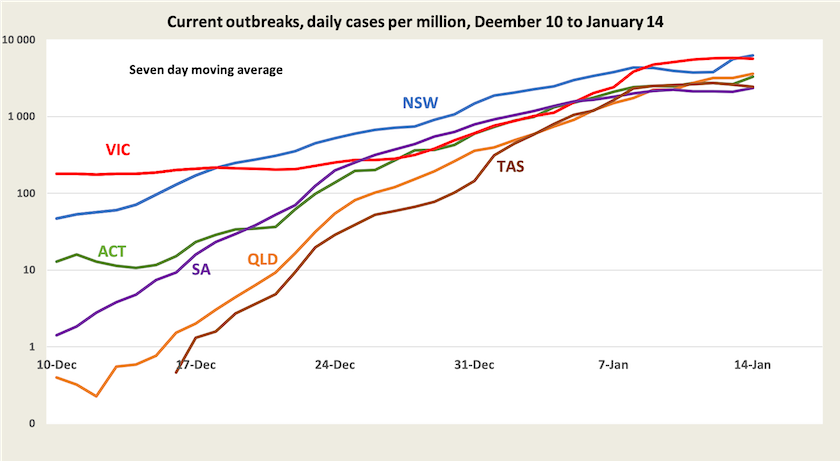

Most media are still focussing on case numbers. Journalists love big numbers, even if they don’t understand what they mean. For what it’s worth, the chart below shows the trajectory of recorded case numbers in each state and territory since they removed restrictions, normalized for population.[1]

The curves appear to be flattening, but this is an impression created by a logarithmic scale, and more importantly the figures on which these curves are based relate only to recorded cases. Only in the last few days have some states started to add in the results of DIY rapid antigen tests, and there will be many – probably an increasing number – people with asymptomatic infections and others who don’t bother getting tested or reporting infections.

Scott Morrison urges us not to look at infections, but rather to look at hospitalisations. That’s unhelpful advice, because when we look at hospitalisations we see an alarming surge, particularly in New South Wales and Victoria. Also we see a strong rise in deaths in those same states. Daily Covid-19 deaths in New South Wales and Victoria are now around 2.5 per million population.[2] If that rate were sustained across the nation it would equate to 23 000 deaths a year, or 50 percent higher than deaths from our present #1 killer, ischemic heart disease. These are big and frightening numbers.

If one checks those death figures against recorded cases, it appears that the death rate is somewhere between 0.2 percent (New South Wales) and 0.4 per cent per recorded case (Victoria).[3]. Those rates are about where countries have been with Delta over most of 2021 – better than the early 1.0 percent recorded before there was vaccination, but still alarmingly high.

In view of these high absolute numbers of deaths and the high rate of deaths per recorded case, it’s hardly surprising that people are scared, and are unconvinced by talk about Omicron being a less dangerous variant. When a prime minister, burdened by a poor relationship with the truth, says “don’t look here”, talks about “pushing through”, and does not engage in a frank discussion about numbers, people are understandably untrusting of any official exhortation to get back to work and spend.

But as Norman Swan and others point out, recorded cases are picking up only a fraction of infections. He believes that recorded cases could be understated by a factor of five. If so, death rates per case would therefore be overstated by a factor of five. Some evidence in support of Swan’s estimate is provided by figures from New South Wales: on Thursday, the first day when that state added DIY rapid antigen test results to its official figures, there were twice as many such cases recorded as the official figures, suggesting we could multiply earlier official figures by at least three – and that’s in an environment when, because of government neglect, rapid antigen tests are very hard to come by. Also Tony Blakely suggests that Victoria’s apparent high death rate per case in comparison with New South Wales may be explained, in part, by the fact that the Delta variant has been hanging around longer in Victoria than it has in New South Wales. The worst cases of Delta can exhibit a long gap between infection and death. We need to wait until Delta is cleaned out before we can make much sense of death rates per infection.

So while the present situation is far less dire than those scary numbers suggest, we don’t yet have reasonably reliable estimates of the real risks. As much as policymakers, businesspeople and individuals would like to be given an indicative probability – “if you contract Omicron you face an X percent probability of hospitalization and a Y percent probability of death” (with adjustments for age and vaccination) – it will still be some time before epidemiologists can provide reasonable estimates for X and Y. All we know, as pointed out in the previous segment, is that there is emerging evidence that the Omicron variant is indeed less severe than earlier variants, even among the unvaccinated.

What New South Wales data can tell us about Omicron

New South Wales has a large population (8 million), has had Covid-19 spreading since mid-June last year, and maintains an excellent set of data on cases, with breakdowns by age and vaccination status (unfortunately with a significant delay – the present data is only up to December 25). That means it should be able to tell us quite a bit about how Omicron is behaving. For those who aren’t addicted to preparing and updating spreadsheets, Juliette O’Brien and her colleagues have taken this data and presented it in easily-read graphical form.

As we look at either the raw data from New South Wales or O’Brien’s presentations, we should remember that it is all based on recorded cases: infections may be many times higher, which means hospitalisation and death rates per case would be many times lower. The next iteration of New South Wales data will probably be even less reliable. The data from New South Wales does tend to confirm the effectiveness of vaccines in protecting against severe disease and death, but it’s too early to draw a more definite conclusion from that data.

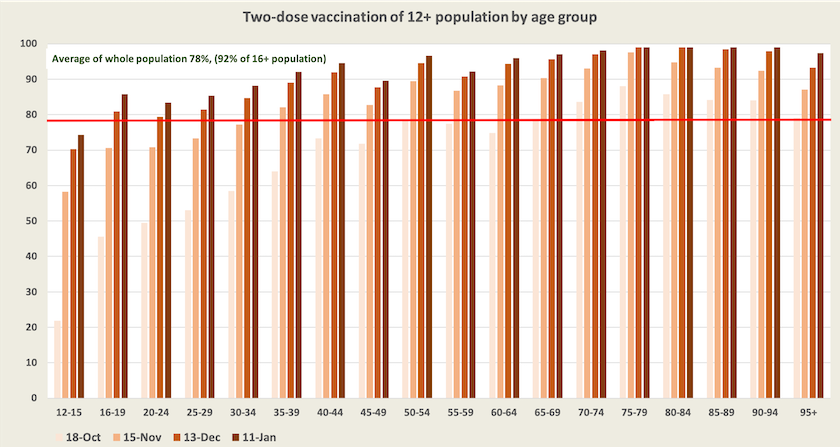

One notable feature of the New South Wales data is in a chart (Figure 4 in the New South Wales report of January 7) revealing a disproportionately high number of young people, particularly in the 20-29 age group, who contracted Covid-19 in the 6 months to December 25, and a correspondingly low number of people over 50 who contracted Covid-19. One possible explanatory factor is that younger people are more mobile than older people and therefore are more likely to be infected. Another possible explanation relates to their comparatively low level of vaccination, as shown in the diagram below. Among Australians aged between 12 and 35, fewer than 90 percent have received two-dose vaccination. There could be around 300 000 unvaccinated young people (not including children) in New South Wales. Also, what we are seeing in those New South Wales figures, which go up to 25 December, could be largely about the Delta variant.

Third doses: how effective are they?

Norman Swan refrains from talking about “boosters”: for our immune system to be able to protect us against serious illness and death, we need three doses of vaccine. It’s still too early to make a precise assessment of the effectiveness of the third dose – so far only 4.1 million Australians have received a third dose – but on Tuesday the Queensland Chief Health Officer stated:

We now have enough data from around 500 patients to see some real trends on who’s ending up in Queensland hospitals and the importance of boosted vaccination is very clear. If you are unvaccinated, you are nine times more likely to end up in hospital than if you have received a boosted vaccination: that is three doses of vaccine.

There was probably a mix of Delta and Omicron cases in that sample, but because Queensland was essentially virus-free until December 10, there would not have been the large mix of Delta cases as there has been in Victoria.

Where to from here?

Almost all discussion about Covid-19 in Australia is about the Omicron variant. Some journalists and commentators seem to believe that Omicron will pass through the population, before retreating into the background like a seasonal influenza: it will gently segue from a pandemic status to a benign endemic status. Others warn of the possibility of yet more mutations, and if a virus emerges that is at least as infectious as Omicron, but is more deadly, we’re all in real trouble.

There is a session last Tuesday on the ABC’s Breakfast program: Covid in 2022: is there room for optimism?, with a lively discussion between Nancy Baxter of the Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, Peter Collignon of the ANU, and David Anderson of the Burnet Institute. All are cautious in their assessments, avoiding categorical statements (except, perhaps, for an acknowledgement that herd immunity is no longer a possibility). If they were to be lined up on a pessimistic-optimistic spectrum, Baxter would be on the pessimistic end and Collignon on the optimistic end, but both present scenarios (not predictions) that are plausible and well-argued.

Anderson reminds us that whatever path the pandemic takes, we should not slip into the idea that we can resume where we were two years ago: for example we should pay ongoing attention to building ventilation, and even if death rates fall to very low levels, we should still be concerned about the debilitating effects of “long Covid”. Similar warnings are made by Raina Macintyre writing in The Conversation: From COVID control to chaos – what now for Australia?. She believes that “Covid will never be endemic. It will always be an epidemic infection, with recurrent epidemic waves”.

Norman Swan on Friday’s Coronacast is very critical of politicians who would have us believe that once we get through this wave it will be “mission accomplished”. (He is also very critical of the way the New South Wales government ignored warnings from public health experts and let the virus rip through the community, overloading the health care system and crippling other parts of the economy). Covid-19 is indeed endemic, but that doesn’t mean it is benign, and there will be new variants. There seems to be some differing definitions among experts about just what “endemic” means, but whether we follow Macintyre’s meaning or Swan’s meaning, they are both warning that Covid-19 is here to stay, that it will continue to be dangerous, and that we will have to take public health precautions into the foreseeable future.

1. Western Australia is not included, and even with a moving average presentation, Northern Territory figures are too lumpy to display.↩

2. This is calculated from a seven-day trailing average. If we consider only the latest daily figure (Friday) the rate would be > 3.0 deaths per million.↩

3. This is based on recorded deaths on a seven-day trailing average, and dividing that by the number of recorded infections two weeks earlier to allow for the time lag between infection and deaths. ↩

Omicron and public policy

There is no shortage of media commentary on the Morrison government’s inept handling of the latest wave of Covid-19. Its failures in providing booster shots, particularly for those in aged care, in arranging vaccinations for children and in obtaining rapid antigen tests, are all well-covered. It’s as if the Morrison government has learned nothing from its failures in earlier phases of the epidemic.

There is a plethora of media stories about the contrast between people’s experience on the ground – seeking vaccinations for their children or aged care residents, shopping around for rapid antigen tests, finding basic heath advice – and the false assurances being made by Morrison and his advisers. It’s reminiscent of the politics of the Soviet Union, when the party elites would be talking about the economic successes of the latest Five Year Plan while the people spent large parts of their lives queuing for bread and other necessities.

Michael West comments on the general incompetence of the Morrison government – a government more intent on looking after its corporate mates than in developing good public policy. Crispin Hull sees a little more pattern in the Morrison government’s policy response: it’s not so much about mindless incompetence as it is about the government’s established practice of crony capitalism.

One particularly relevant revelation is that in August a group of public health specialists made an hour-long presentation to a group of federal parliamentarians, Labor and Coalition, warning that the PCR system would be overwhelmed and that the government should quickly shift to rapid testing. But although Coalition members were receptive to the presentation, the government made no attempt to act on the group’s recommendations. (Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised when we have a government that is contemptuous of parliament.)

Another particular stupidity has been Morrison’s categorical refusal to provide free rapid antigen tests available for all. Writing in The Conversation three academics from Flinders University put the economic case for free rapid antigen tests. Their piece is all basic and orthodox benefit-cost analysis, which would be familiar territory for any economist on the public payroll. But Morrison has exempted himself from taking advice from economists: he has been endowed with an instinctive feeling for what constitutes good public policy.