Economics

MYEFO – spun-dry economics

On Thursday the Government released the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook, known by its acronym MYEFO.

As has become increasingly the case with Treasury documents, it is written with a political spin. It has a stand-out box on the Commonwealth’s response to Covid-19, and claims about how the Commonwealth has done so well in securing vaccines and strengthening the health system. In a section “Investing in infrastructure” the text reads as if the Morrison Government is doing something to attend to our transport backlogs, but the actual numbers are paltry – $110 billion over ten years or about $100 per household per year. It has a whole section on the “National Hydrogen Strategy” (note the capitalization and the word “strategy”), which is actually about an outlay of $160 million over 5 years, or $32 million a year.

These and similar sections will no doubt be used as cut-and-paste opportunities by partisan journalists to tell us how well the Morrison government is performing.

Economic projections – the legacy of poor productivity

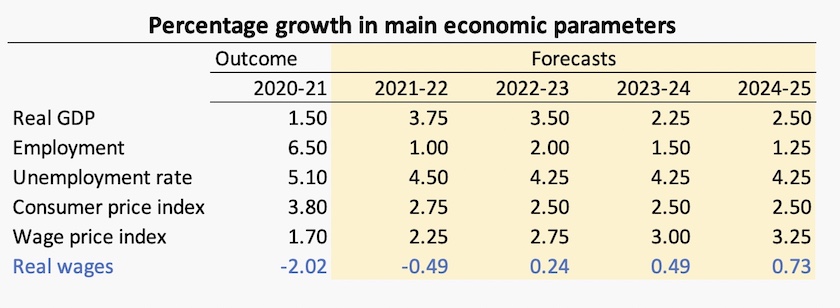

In all, the MYEFO, in spite of the term “economic” in its title, actually has little to say about economic structure. Its economic content is mainly about a set of medium-term economic projections, captured in a table “Major economic parameters”, reproduced below, with the addition of one more line to show projections of real wages, obtained by discounting the projected wage price index by the projected CPI.

In none of the projected years are wages expected to rise by 1.0 percent or more. In fact if we multiply out all the wage growth figures from 2020-21 to 2024-25, we find there will be a small decrease of 1.0 percent in real wages over this five-year period, or, if we leave out 2020-21, there will be an increase of only 1.0 percent. In plain words it envisages another five years of stagnant wages.

That forecast roughly aligns with the real GDP forecasts in the outer years. In terms of people’s material welfare GDP itself is meaningless: what counts is GDP per capita. In the years 2023-24 and 2024-25 net immigration is forecast to be about 224000, or 0.9 percent a year. Added to natural increase of 0.6 percent a year, that means our population will be growing at about 1.5 percent a year, while the economy is growing at only 2.25 to 2.50 percent a year, leaving little for growth in GDP per capita.

If the government were honest with the people it would include projections on real wages and GDP per-capita in this document, but it doesn’t want its economic failures exposed to the world. Those important estimates are so poor because they reflect our miserably low productivity performance, a performance that’s been falling over the eight long years of Coalition governments. Unsurprisingly the MYEFO has nothing to say about our productivity performance.

This year’s real GDP growth of 3.75 percent seems to be optimistic, but it’s coming off a low base. In fairness to the MYEFO’s authors it would have been largely finished before Omicron turned up: budget documents take months of work. MYEFO simply makes the confident assumption that “The Omicron variant is not assumed to significantly alter current reopening plans or require a reimposition of widespread health and activity restrictions.” Further on it develops two scenarios around Omicron, the more pessimistic one involving activity restrictions such as physical distancing, density limits, and targeted lockdowns later this year, combined with some caution on our international borders. That would have the effect of holding GDP growth back for a few months.

The reality, however, is that even in the unlikely event that we can get through the Omicron outbreak without any mandated restrictions, it will still have a chilling effect on economic activity. Even if people’s fear of death and disease subsides, uncertainty associated with the pandemic does not. People are understandably deferring making personal and business plans, and will go doing so until there is some end to the pandemic.

Fiscal projections – the Coalition’s “small government” obsession

MYEFO is not only an economic forecast. It is also a fiscal forecast, and many media tend to focus on fiscal indicators – deficits and government debt – even though these are much less important for our long-term prosperity than our economic structure.

Its fiscal statement makes much of higher tax receipts and lower outlays compared with the budget, but these are meaningless: the budget estimates were understandably a shot in the dark.

Not so meaningless, however is the Coalition’s mantra of “maintaining a sustainable tax burden consistent with a tax-to-GDP ratio at or below 23.9 per cent of GDP”, an arbitrary figure that takes no account of the need for higher government expenditure as an economy grows, and our already very low public expenditure in comparison with other prosperous countries. As Treasurer Frydenberg says, without any reason or justification, the Coalition’s philosophy is that taxes should be lower. A more honest frame would be to say that, regardless of our need for public services – education, health care, community safety, infrastructure – the private sector should be favoured, even if these services could be provided more efficiently and equitably in the public sector.

MYEFO reflects this priority. Although nominal GDP is expected to rise by 23 percent between this year and 2024-25, personal income tax is expected to rise by only 12 percent. This is almost certainly a result of planned tax cuts in 2024 for people with higher incomes – described by Ross Gittins as economically irresponsible in view of the way the world has changed so much since they were legislated in 2018.

At least those tax cuts are on the public record. MYEFO also includes $16 billion for “Decisions taken but not yet announced and not for publication” – $5.6 billion this year, and lesser amounts in following years. Car parks, sports buildings and other boondoggles in marginal electorates come to mind. Yet an essential aspect of responsible and accountable government is that funds are appropriated for specific purposes. For parliament to have passed a budget approving large sums without specified appropriation is a failure of accountability, but one of our dysfunctional conventions is that budgets either get waved through parliament, or, as in 1975, are entirely blocked.

Perhaps the most pathetic and partisan aspect of MYEFO, however, is its statement of risks. There is nothing about climate change.

A bleak Christmas for many Australians

Economists are talking about billions in household savings, accumulated during lockdowns and other restrictions, about to be unleashed in pre-Christmas shopping.

There has indeed been a boost in national saving over the last couple of years. Some of it would be precautionary and some would be pent-up demand. But as with income and wealth more generally, it is not distributed evenly. Based on a national survey, the Salvation Army finds that many Australians (41 percent) are feeling more financially stressed than they were a year ago. It finds that 14 percent “are worried about being able to afford enough food to eat”, 21 percent are worried about paying their utilities, and 29 percent feel lonelier than they were a year ago.

These are national figures. The Salvos also report on the conditions of those who have sought its services, revealing pockets of deep poverty, loneliness and distress.

Trade unions

Stories out of the USA suggest that trade unions are re-emerging as a force, although membership there, as in Australia, is still on a long-term downward trend, and some are suggesting that present union activity is transitory as American companies and their workers work out new arrangements in a post-pandemic world.

Here, the ABS has released its series Characteristics of employment, covering pay systems, working arrangements, and trade union membership.

Its supporting survey on trade union membership covers the period 1976 to 2020, when membership fell from 51 percent to 14 percent of people employed. Only in four sectors – “Education and training”, “Public administration and safety”, “Health care and social assistance”, and “Electricity, gas, water and waste services” is trade union membership above 20 percent, but it has fallen in all four sectors since 2014. Notably the first three of these sectors are predominately in the public sector.

The stereotype of the unionist as someone, usually male, working in manufacturing, construction or transport, is dated. If we were to develop a stereotype today she would be a graduate classified as a “professional”, and earning more than people in sectors that were traditionally unionised. In fact the only promising figure in these statistics is that there was a small increase in trade union membership among women between 2018 and 2020.

The media has given some coverage of the ABS working arrangements data, part of the same survey, where it is revealed that well before the pandemic there was already a trend for more people to be working from home. The pandemic seems simply to have given this movement a boost. The same document reports on other aspects of employment conditions: notably benefits of sick leave, paid holidays and parental leave, while covering three-quarters of employees, are not shared by the poorest-paid quarter.

Trains, buses, ferries, cars, bicycles, feet

Not all public transport is for the needy – Sydney’s Manly Ferry

The Productivity Commission has published a rather long research paper Public transport pricing. It’s broader than its title implies, for it covers most forms of urban transport, because there is complementarity and substitutability between public transport and private transport – mainly people’s own cars. (It’s disappointingly light on cycle and pedestrian transport, however.)

As one would expect from the Commission, it takes a mainstream microeconomic approach. The price charged for public transport should equate to the marginal cost of providing the service, taking into account all externalities, including, for example, the fact that public transport reduces road congestion (it demonstrates that road congestion costs around $24 billion a year). It finds, however, that public transport fares have tended to be set by an ad hoc process with little regard to equity or efficiency.

It does not dispute the case for subsidising public transport, but it does argue for higher peak charges. Simply reducing public transport fares to encourage people to switch from cars to public transport is a crude and ineffective way to deal with road congestion compared with proper road user charging.

It rebuts the notion that public transport is a mode for those who cannot afford cars. While it acknowledges that for the very poor who cannot afford a car and those who cannot drive, public transport is an equitable and low-cost alternative, particularly for off-peak travel, it finds that some modes, particularly urban rail, tend to be used disproportionately by the well-off, who have good CBD jobs with regular hours.

Our poisonous political troika

In the (unlikely) event that you have 100 minutes to spare you might watch a book launch at ANU introducing Transitioning to a prosperous, resilient and carbon-free economy. Ignore the elevator music at the beginning: Brian Schmidt comes in at 5:00, Malcom Turnbull comes in at 15:30 and discussion with the authors starts at 40:00. Writing in Renew Economy Michael Mazengarb summarises Turnbull’s speech, in which he calls out the poisonous political troika blocking action on climate change: “Right-wing politics, populist politics and science-denying politics. Right-wing media, principally that owned by Mr Murdoch. And of course, the vested interests of the fossil fuel lobby. Probably the only rational part of that Troika.”

Also on climate change Hugh Saddler has launched a new publication Australian Energy Emissions Monitor, published on the ANU website. The first edition finds that “emissions are on trend to return to pre-pandemic levels, if not higher”. In a special section on South Australia it has promising data on electricity prices from renewable sources compared with coal-fired sources. Another notable finding in this document is that the pandemic has resulted in a big reduction in use of aviation fuel.

Horticulturalists behaving badly

The ABC’s 730 Report on Tuesday night had a 10-minute segment – The unseen workers propping up the farm industry – focussing on a fruit grower on the Murray, fed up that he has to leave fruit rotting on the ground, because he is unable to get labour, and because he knows that he is competing with criminals doing deals with labour hire companies to use undocumented (i.e. illegal) immigrants, paid as little as $30 a day and housed in squalid accommodation. Nationals MP Anne Webster, whose electorate of Mallee takes in much of the fruit-growing industry, seeks a better deal for foreign workers in the industry, but the Department of Home Affairs, so keen to protect us from asylum-seekers, seems to be unconcerned about these undocumented workers.

Also reporting on the same industry, ABC Rural reporters Michael Condon and Keely Johnson report that many horticulturalists in New South Wales have been caught stealing water: More than 150 landholders across NSW caught red-handed breaching water laws.

This seems to be an industry in which the regulatory hand of government is absent, to the detriment of the whole industry as honest and ethical companies, unable to compete with criminals underpaying employees and stealing water, are forced out of business. Is this what Morrison and his fellow travellers want when they talk about getting the government off our backs?